Horror. Horror is a reaction. The very definition of the term derives from the Old French word orror, which means “to shudder or to bristle”. It evokes a response. It provokes feelings of repulsion, even dread. It stimulates and feeds the primal fight or flight response and, in so doing, offers relief through the acknowledgment of one’s own present safety.

Horror is a tricky business in comics because, unlike film or campfire stories where creators conduct the presentation, in comics, the reader controls the pacing. It takes an artist in complete control of every aspect of the medium to make something truly scary. Julia Gfrörer is such an artist.

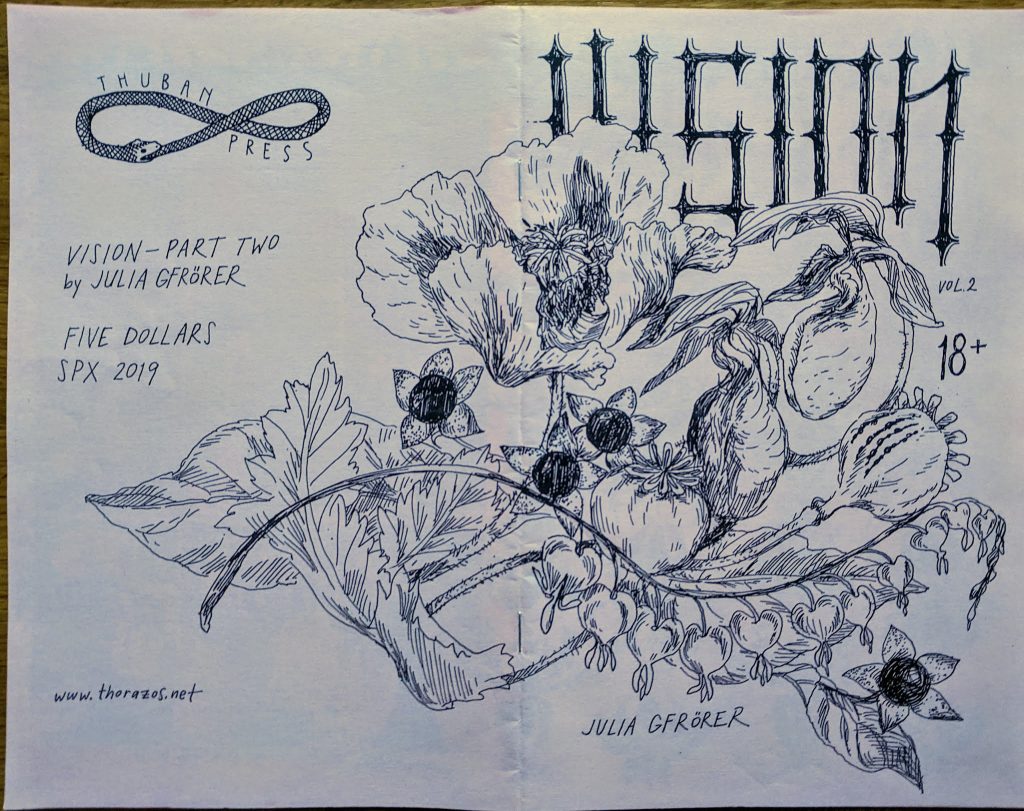

Gfrörer has been creating works of Gothic Horror and transgressive fiction for at least the last decade, usually using a regulated nine-panel grid filled with the spidery linework that characterizes her cartooning to tell stories of witches, mermaids, plagues, martyrdom, eroticism, and the oppressive nature of religion and society — especially as they relate to the agency of women. Her latest work, Vision, is a serialized zine, self-published through her Thuban Press imprint. She released the second volume in September 2019.

As with many of Gfrörer’s comics, there is a constant thrum of unease in the narrative of Vision, as if something truly evil is on the horizon waiting to be given its due. Set in a Victorian past, the story centers around a brother and sister, the brother’s sick wife, and an entity that lives in the mirror of the sister’s room. The sister is recently widowed, and, as such, is of diminished status in the sociopolitical norms of the times. Despite her grief, and at the expense of her own health, she is relegated to being the caretaker for her brother’s wife, who is suffering from some unnamed debilitating ailment.

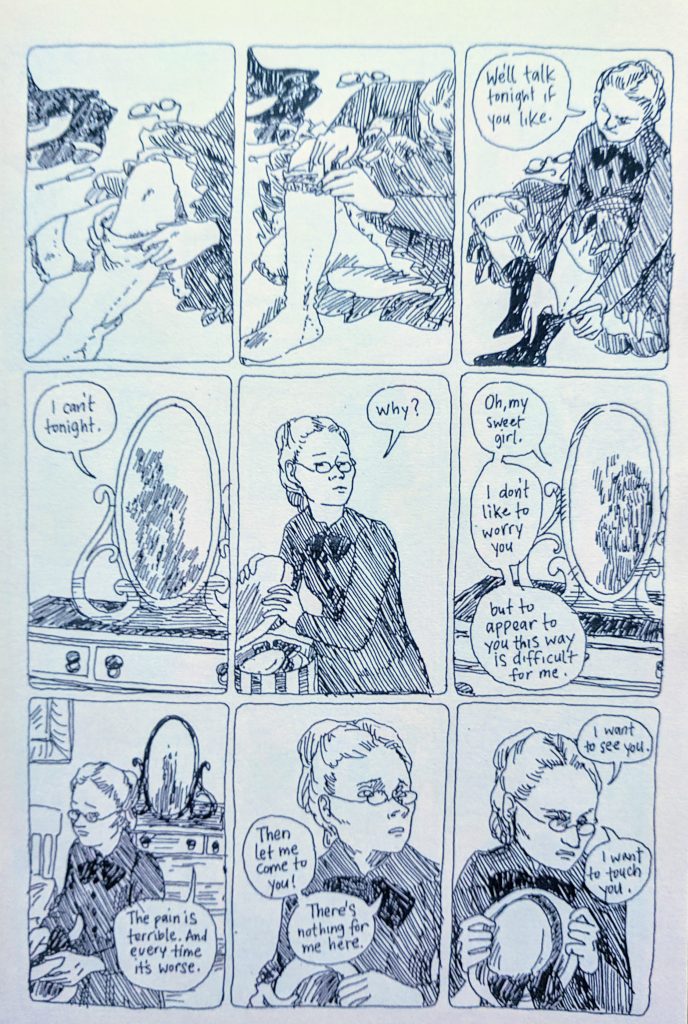

In the first volume of Vision, Gfrörer reveals that the widow is engaged in a relationship with a mysterious entity that appears to her in her dressing mirror. Separated by the glass, the relationship is noncorporeal, voyeuristic, and masturbatory in nature. Over time, the relationship with this entity grows, and through it, Gfrörer blurs the reader’s sense of reality. In one scene in the second issue, the entity in the mirror claims that appearing before the widow causes it extreme pain. The widow asks to join the entity on the other side of the mirror but is denied. There is a sense that all this may be the product of the imagination of a disempowered woman. There’s manipulation inherent in the narrative, so much so that the reader is not sure of the reality of anything in this comic. This feature is what makes Gfrörer’s work so compelling; the reader is pulled along by a need to make sense of things. Unanswered question piles upon unanswered question.

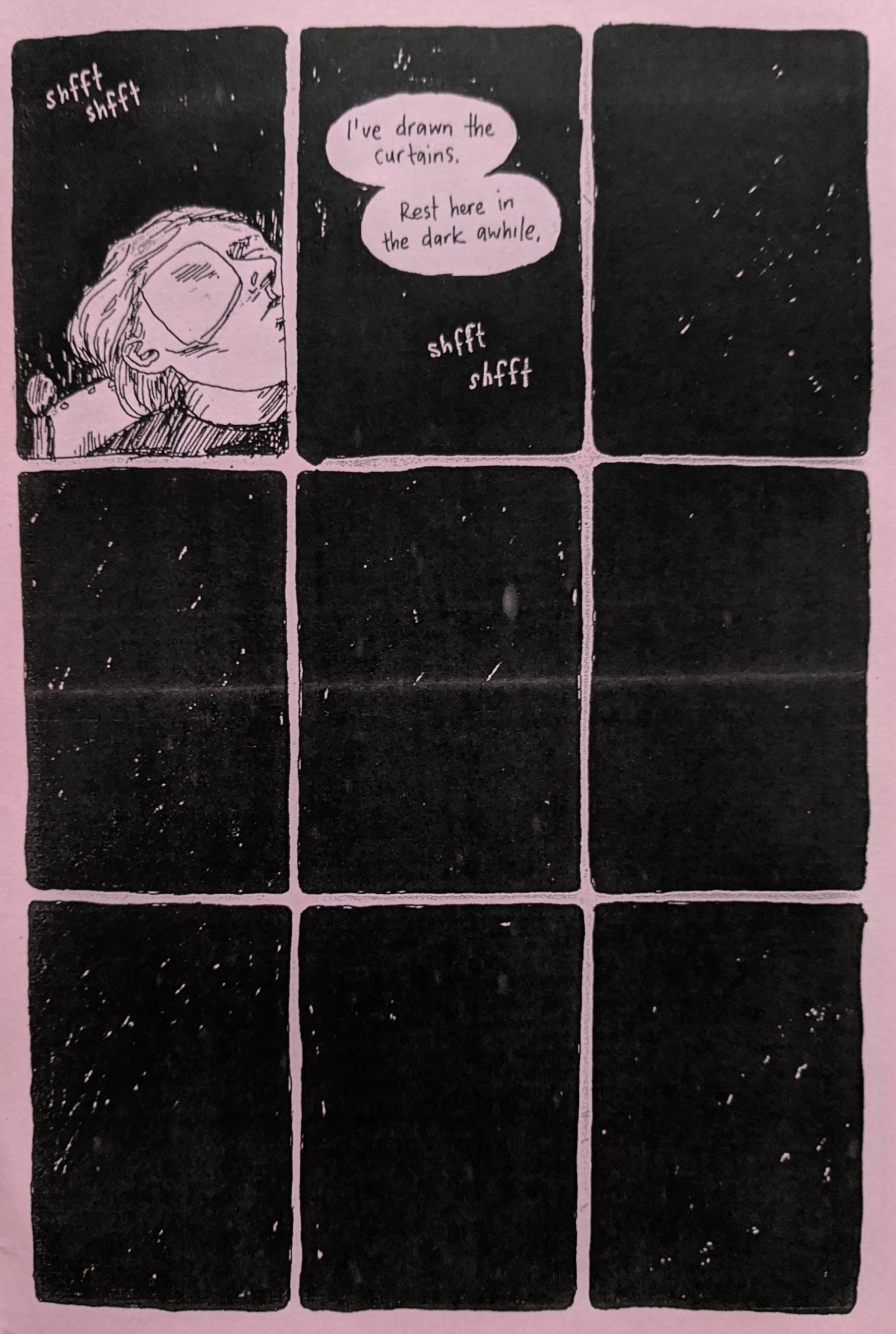

This second volume of Vision focuses even further on the idea of sight. The last half of the comic is devoted to the widow’s compromised vision. There is a cataract on her right eye that obscures her ability to see. In a horrific scene reminiscent of the opening of Luis Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou, the doctor couches her cataract with a scalpel, dislodging the lens to remove its opacity. Gfrörer follows this operation with 28 panels of complete blackness speckled with small translucent dots covering four pages, essentially completing the volume. It is a bold choice for an artist to cover almost a fifth of their comic in blackness. And yet here it makes sense. Here Gfrörer furthers the manipulation of the narrative and her themes. This sort of extended darkness builds the tension and adds to the disquiet. The reader is left to wonder what the character will see once her sight is restored.

Anticipation combines with the thrum of unease at the heart of this series to pressurize speculation. Could it be that the real horror might be found in revelations at the conclusion of the series? Suspense invests the reader to want to read on.

While Vision is a great model of horror, it is also truly a work of transgressive fiction. The reader expects a level of agency from Gfrörer’s female characters. Not content with the role assigned to her through society and circumstances, the main character has come in contact with something that will potentially empower her. The burning question is this: will this entity lead to her salvation or damnation? In the vulnerability of pain and loneliness, will there be empowerment for her or some kind of otherworldly predation? Therein lies the greatest horror of all.

Horror is a reaction. What we are given to interpret in Volume 2 of Vision feels horrific. Julia Gfrörer plays on fundamental fears and touches masterfully on that which causes us to quiver.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply