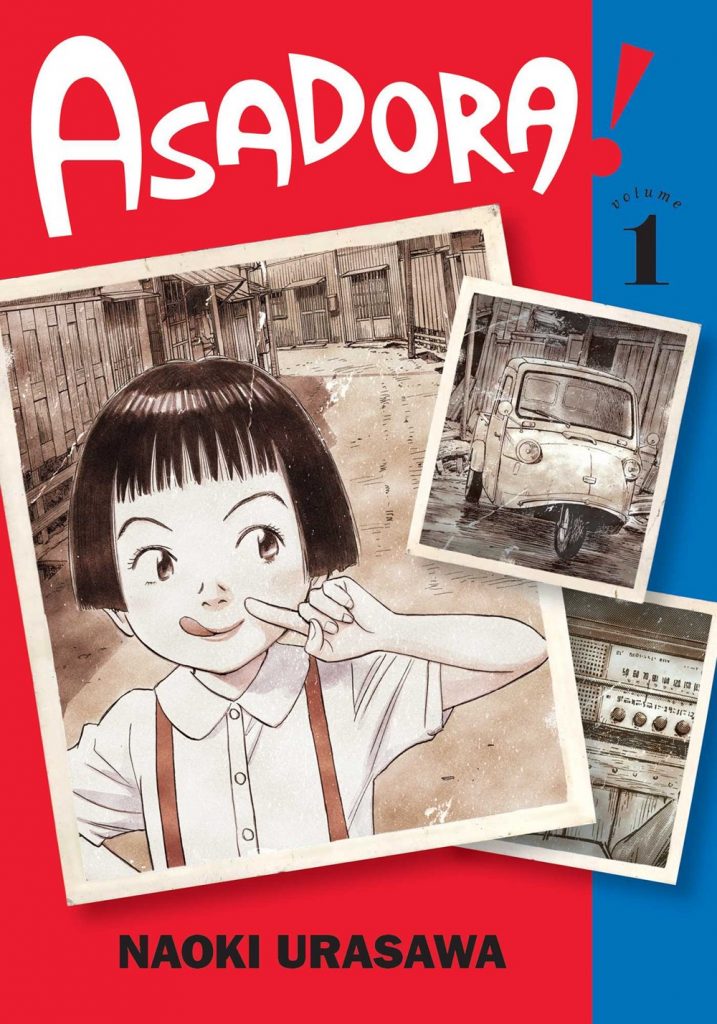

Volume 1 of Asadora, the new series by Naoki Urasawa (20th Century Boys, Monster, Billy Bat) opens big. As big as it gets, with a vision of apocalyptic devastation in the year 2020, before pulling back to tell the story of a seemingly normal, if extremely willful and capable, little girl. This is a technique he has used before; 20th Century Boys opens with a promise of a world saved before focusing on the lives of a few normal people who used to be friends in high school, and Pluto starts with a massive fire destroying one of “the world’s greatest robots” before shifting gears towards more low-key detective mystery. Whenever he writes a “little” story, it’s always with a promise of something larger, something world-shaking, waiting in the wings.

This is far from being something unique to Urasawa (Brian K. Vaughn is a fan of this little trick as well) and it’s hard to deny he does it with particular panache. In fact, it’s hard to deny that Urasawa does everything with panache, both in terms of writing and art — his world-building, his character work, his environments, his expressions, his ability to continuously tease the readers to follow his serpentine tales volume after volume… this is a man who has honed his craft and personal style to near perfection. So why am I not satisfied?

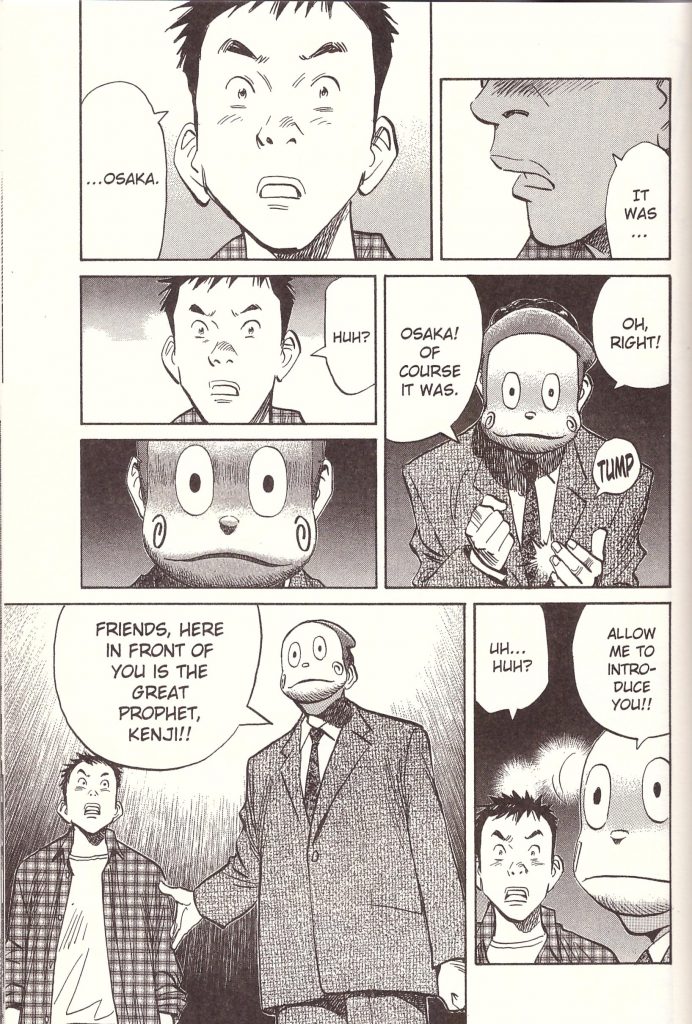

It’s not just with this particular opening volley. This would be my fourth venture into the world of Urasawa, and, with one exception (more on it later), they all seem to suffer from the same basic flaw: I can see the strings. These strings are pulled by a puppet master, whose artistry I can admire, but I can still see them. For all of his vaunted skill as a humanist storyteller, one who likes to put “normal people” in the center of his stories, these stories always end up going the route of the grand mystery. It’s as if Urasawa doesn’t trust his the readers to simply enjoy living in these worlds he has crafted; His mysteries are constantly being built-up and teased in a rather overdrawn manner (if you take out all the reaction shots to some unseen revelation in 20th Century Boys, you’d probably cut the series in length by 20%), so they can never quite satisfy. Nothing can. By the time 20th Century Boys ended, I must admit I wasn’t quite sure who was the secret person at the heart of the story; too many faux-revelations dragging things down, too many characters, too many turns, too many almost-but-not-quite moments. Really, just “too much” of everything.

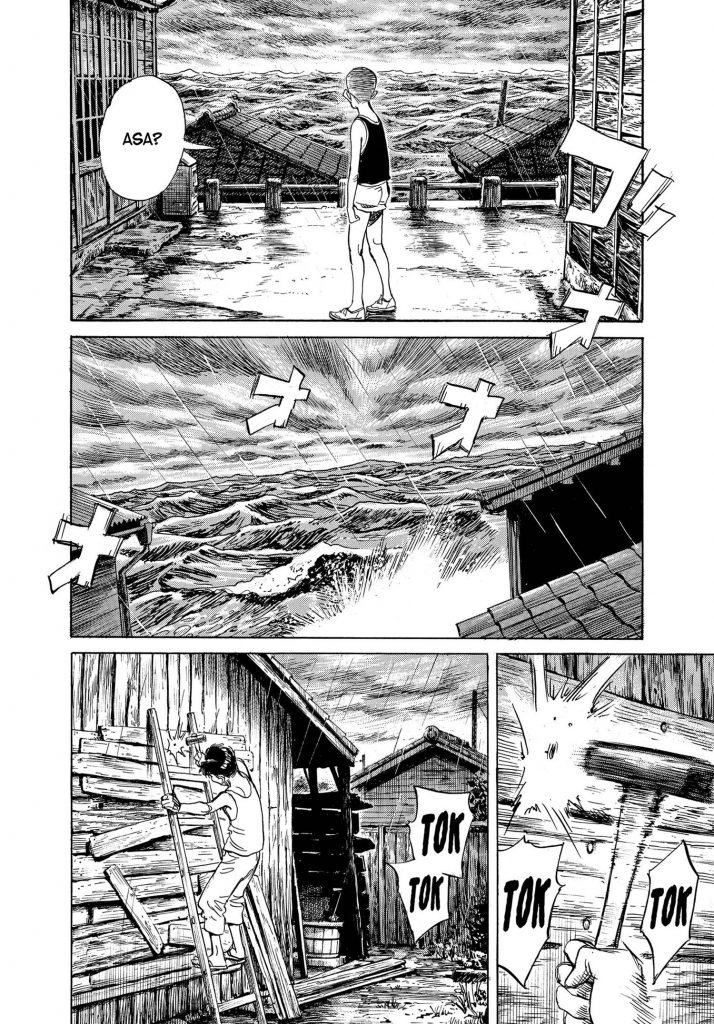

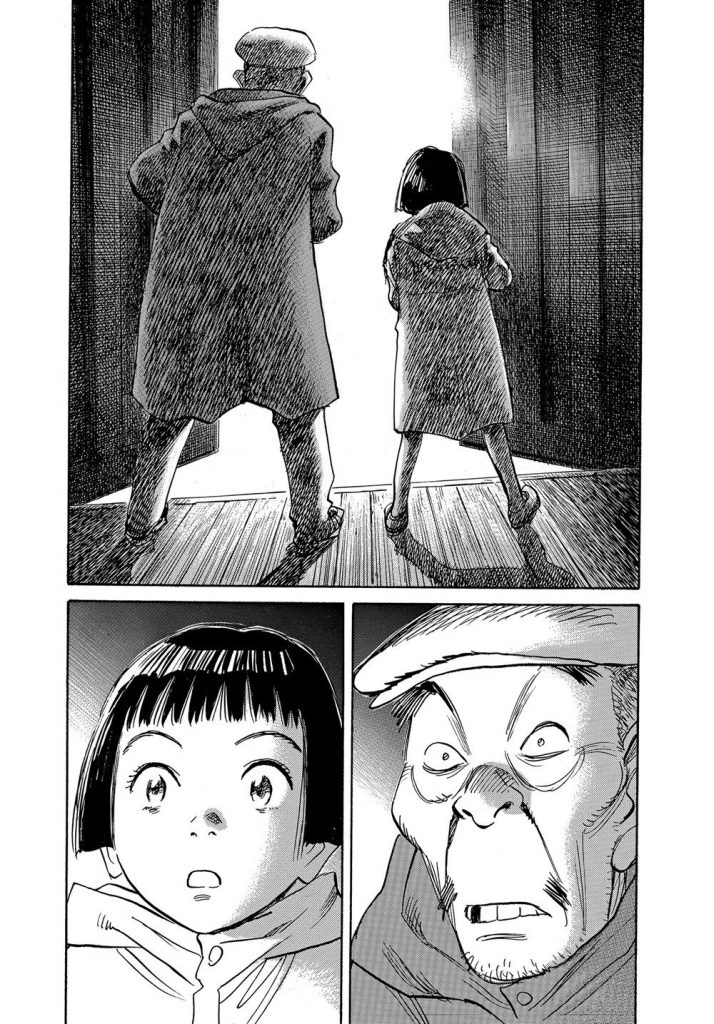

In fact, if you remove the hints of something absolutely massive that is about to occur, Asadora vol. 1 would probably be a much better comics. The main story in the volume, the titular girl finds herself locked in a room with a thieving old man during a sudden hurricane and the two of them having to join forces to help save as many people as possible after the storm passes, works well enough of its own. Again, you can see the strings. When the Old Man tells Asadora he used to be a pilot in the military but can’t find a job in the civilian life, we know he’s going to end up using the plane we saw in his flashback. When we meet the stern-eyed owner of the restaurant, we know she’ll agree to make up the food necessary for the starving people. This is the fine sort of string-pulling because although one can recognize where the story is going, the emotional impact is not lessened – the question is how does the artist get us there.

And Urasawa surely gets us there in a stylish manner. At this point in his career his art is as self-assured as it ever was; he knows exactly what he wants to achieve and how to go about it. A chapter taking place entirely within a small closed room, composed mostly of two people talking, should be the kind of dull thing that leads critics to reach for Wally Wood’s 22 Panels that Always Work, but Urasawa makes it work. The reader becomes so intrigued by the subject of the conversation, by the rhythm of the exchange, that all such issues are thrown aside. “Show, don’t tell” is a suggestion, not a rule, and one that does not bind a superior storyteller.

What’s more, the chapters that follow it build up from this sense of confined space by featuring large open shots of devastation, showcasing the damage brought about by nature’s might. A silent spread of the devastated city, standing in contrast both to the narrow confines and talky nature of the previous chapter, allows both reader and character to grasp the scope of the damage inflicted on this community. Truly, Urasawa can do it all.

Yet, instead of being focused on these things Asadora does well, in the story of these particular people, in this particular time and place, my mind constantly drifts away to the “big mystery”. The here and now of the story become an afterthought to the larger questions which will soon be introduced. Urasawa obviously could tell smaller, self-contained, stories (such as the first few Master Keaton stories), he simply chooses not to. That choice constantly naturalizes a lot of his better qualities, leading to series that are more surface than content, more interesting in shocking and surprising, and outwitting his readers rather than engaging with them.

All these twists and turns end up leaving the human element behind, focusing the stories more and more on the large overarching plot in a way that negates the author’s obviously humane intentions. At a certain point, it becomes mechanical, an aping of genuine emotion rather than the creation of one. The stories move from one carefully crafted moment to another instead of letting the characters develop.

I’m thinking of something like Summit of the Gods as a good contrast. Yes, that story also has a large central mystery in its center, and it could certainly be accused of dragging its feet as it adds more layers to it, but that mystery is simply a way to anchor the characters and show us their world. It does not dominate the manga; it merely establishes its reason for being. One can return to Summit of the Gods over and over again. It’s not the mystery we return for – but the emotional and physical journey the characters go through.

More negative critics have referred to Urasawa derisively as an “airport writer,” a maker of populist potboilers. I don’t think that’s fair, partly to Urasawa (whose ambition is far greater than the Lee Child / David Baldacci / Harlan Coben set), and partly to these authors who know their limitations perfectly well and work accordingly within them. If anything, I wish Urasawa would lean more towards this direction, be a little more trashy, a little less ambitious. As-is, Asadora continues on the same well-trodden path; the more Urasawa tries to be the biggest and the best, the more artificial and dull his work becomes. All the skill in the work can’t quite cover these faults.

If anything, craft becomes the enemy of art. The cleanliness and “prettiness” of Urasawa’s images simply accentuate the machine-like nature of it all. His shots of a ruined city are so beautiful to behold that they lack the ugliness of ruined lives and broken people. The work shows all the detail but not the proper impact of such devastation – I can see it, but I cannot feel it. Like his characters, Urasawa ends spending a lot of Asadora Volume 1 flying in the air, up and above the worries of lesser people.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply