The Britain of The Impending Blindness of Billie Scott is an unstable place. Its streets wobble as they stretch out into the middle distance, buildings that should be straight-edged bend, the ground is always a little uneven. This uncanny presentation of the streets makes real the social and political reality of the UK for many. Nothing is safe to stand on. There’s almost no support as more and more people become more and more vulnerable. A decade of government cuts, a confusing and punitive welfare system, and rising costs of living with stagnant incomes, exasperated now by a lackluster, inconsistent response to the Coronavirus pandemic, have left many people in precarious positions with little room to restabilize.

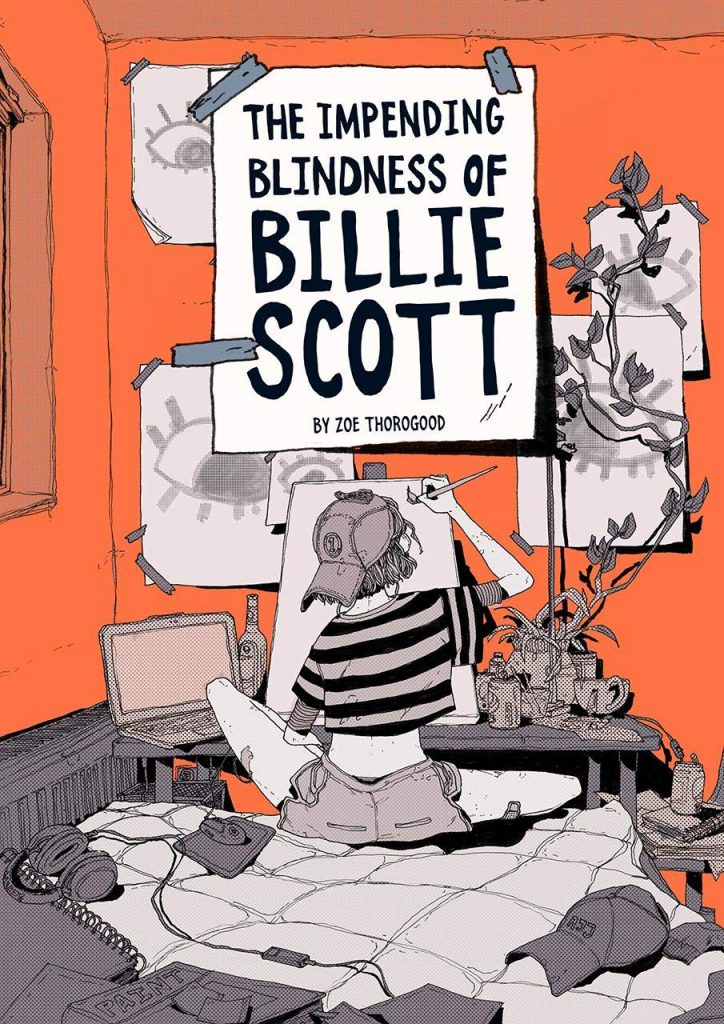

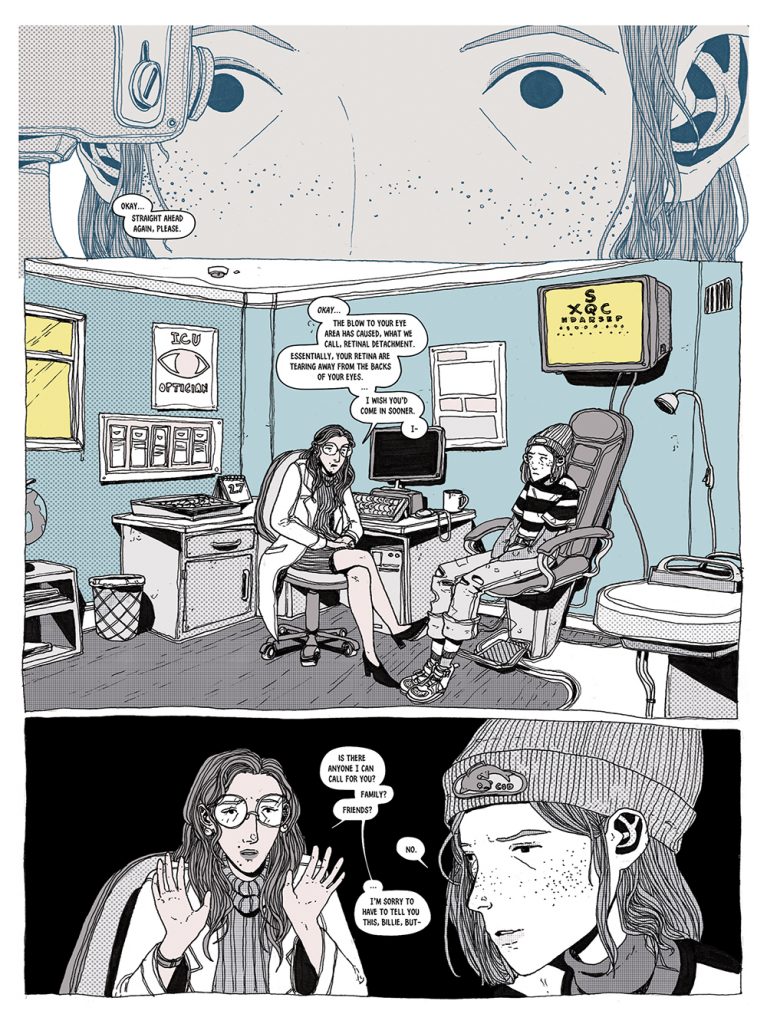

This is the place that Zoe Thorogood’s debut graphic novel from Avery Hill sends us, a country of uneven, slippery streets and uncertain futures. It’s where we find Billie Scott, a reclusive artist living in the attic room of a cheap student house in the North-Eastern town of Middlesbrough. Focusing on her art, she has removed herself from the world, leaving herself isolated and stagnant. Two things happen to pull Billie into the world: the first is an invite from a London gallery to exhibit ten new paintings; the second is an injury to the head that is leading to a rapid deterioration in her sight. Billie needs to find 10 new subjects for paintings in the two weeks the doctor estimates she has until she loses her vision. Suddenly, she has the purpose she was missing, a mission to get her out of stagnation. Things are clearer now that clarity has a deadline.

This launches Billie on a heartfelt, earnest almost to the point of twee adventure through the streets of London, as she hops on a random train to find interesting people to paint. Even though it starts with her literally running to the train before befriending a raucous hen party, what this trip represents, for both Billie and the reader, is a chance to find footing in the jagged cities, to stop and look around.

If you look at almost any city street in modern Britain, you’ll see homeless people, and it’s into their world that Billie stumbles. With very little money, no real plan, and nowhere to stay, she spends her first night in an alleyway behind a pub. This is where she starts to meet interesting people for her portraits.

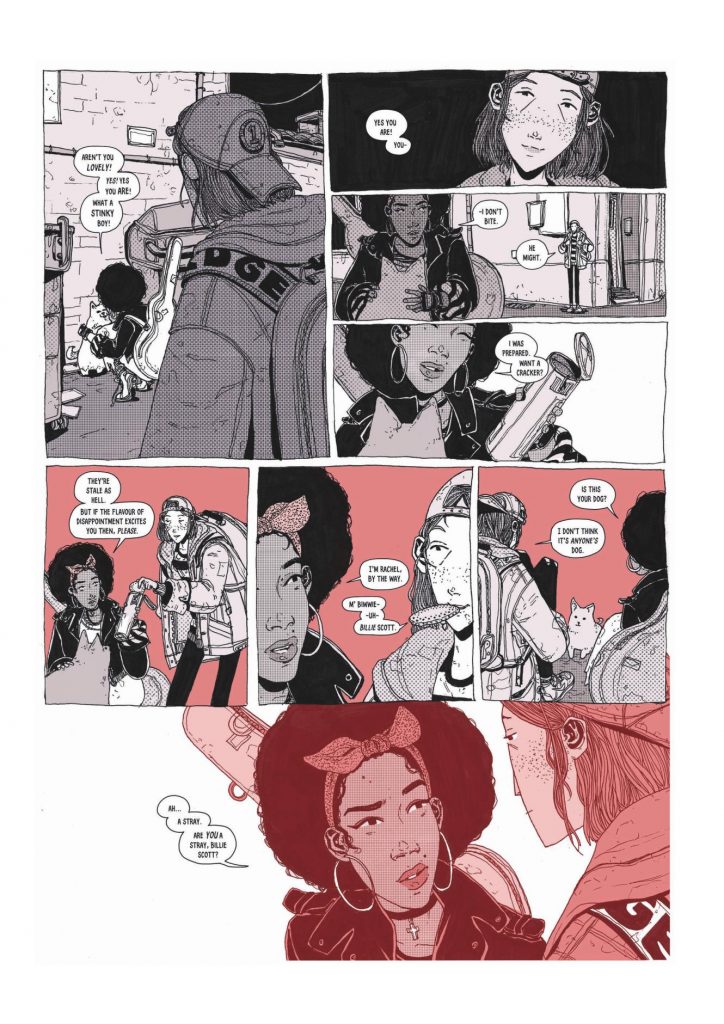

There’s a former soldier, whose life fell apart due to PTSD from the Falklands War, who takes her under his wing, introducing her to his community at a shelter. He’s stony and methodical but has an underlying warmth under his scraggly beard. There’s the edgy girl who brings wine into the shelter and finds the charity workers patronizing. Later there’s a bald writer who eats a lot of beans and makes jokes about having one arm (also a description of me). But the most important person she meets is Rachel, a determined folk-punk busker on a mission of her own, who helps Billie out of her shell, and in the process becomes very close with Billie.

This story could easily fall into poverty porn, ogling at those worse off than us. But the key driver of Impending Blindness, and Billie the character, is relentless empathy and positivity. It takes all the characters, from Billie to the stray dog that comes and goes from the pages as he pleases, at face value. Everyone is worthy of attention and being listened to, particularly if they are in a position that is often not heard. Even when this leaves Billie open to betrayals, the positive impulse is never questioned.

The only thing that I think could cheapen this is that not all of Billie’s subjects are as forgotten as others. As well as the homeless, she paints the bride from the hen party on the train, her student housemate, and that dog I just mentioned. But then I also think maybe it’s good that she doesn’t focus on just the homeless, because it repositions these people who are usually left at the fringes of society as a part of a larger mix of ordinary people.

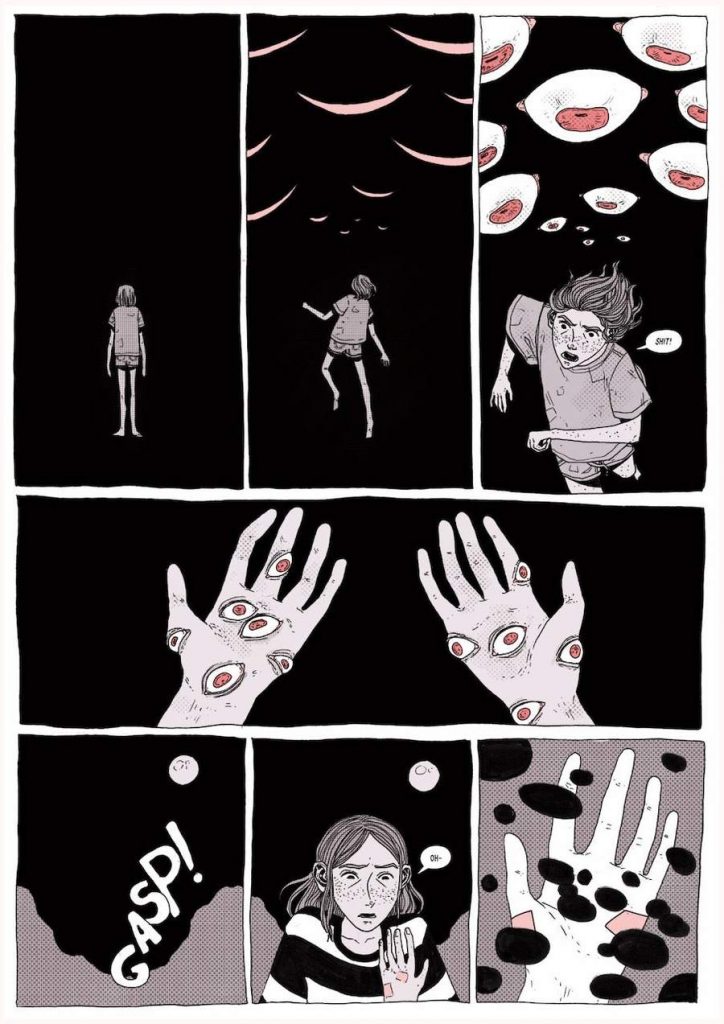

Whether this dilutes the representation of the unheard is a question of how you see. How Billie sees is changing, both literally and figuratively. As black spots pepper the occasional POV panel, her focus shifts away from her insular self, and towards concentrating on the people around her. It is necessary for the sake of Billie’s story, not to be just about seeing homeless people, but seeing as many people as she can before she can’t. This gives Thorogood a chance to show off her skilled, careful depictions of all kinds of characters, with long limbs energetically bending through panels, and every strand of hair seen bouncing as characters move, her people feel more tangible with every page.

But this does prompt another potentially questionable aspect of Impending Blindness, that using a disability as a storytelling device, and a pretty unsubtle metaphor about seeing the world more clearly, could be a little patronizing for disabled people. My disability certainly isn’t a narrative device, and using it like that does little to reflect my experience as a disabled person. Thorogood doesn’t do what I expected with Billie’s blindness though. The metaphor is there for sure, but it’s so obvious that she doesn’t need to give it much focus. Going blind makes Billie’s arc more urgent, but it’s not the point; the point is about learning to live in the world, with people.

Making the blindness secondary feels more like the actuality of living with a disability. Being disabled means you have to learn to do some things differently for yourself, certain things are harder or slower or maybe you need help, but those things quickly become normal, that quickly stops being the story of our lives. Being disabled for my whole life, the shock-adjustment narrative is not nearly as relatable as seeing someone living their life while disabled. Billie does have that shock that I never had, but still has to keep moving forward, even more so now that there is this ticking clock. It changes how she interacts with the world, sure, but focusing on the struggle of adjustment reduces the character to her condition. Other critics have said that the blindness is under-explored, but I am not so sure.The presence of disability always hangs over the book, from the title to the very last page, disability is unavoidable here. It’s just that the disability isn’t the point of the character’s arc; it’s a fact of her life that she doesn’t have control over. If the disability was more of the focus, the same plot could easily fall into a dull, patronizing sob story without much care for the actual experience of disability. But Thorogood knows when to pull back and let her characters breathe; it can be much more effective to leave things less said.

The magic of The Impending Blindness of Billie Scott is that it is so simply empathic. It comes to potentially problematic perspectives but never falls into them. Thorogood presents all her characters without prejudice; they are all people with struggles in their lives, who might be overlooked by society and systems, but they are finding hope and creative outlets in their friendships and communities. In a lot of ways, this isn’t a subtle book; what you see is what you get. But there is still an incredible amount of care on every page. Rather than focusing on the obvious struggles faced by disabled people, or homeless people, trapped by circumstance, Thorogood instead chooses to focus on the more interesting parts of their stories, the things that they can change now. It asks us to stop and think about what we see around us every day, and how we see it, to take a step back from the chaos of the world, and find our footing with our friends.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply