George Wylesol is one of comics’ most idiosyncratic storytellers. In 2019’s Internet Crusader he cemented his lo-fi digital aesthetic in an experimental narrative that was told purely through a computer screen. In Internet Crusader, we watched through the eyes of BSKskator191 as they saved humanity with their desktop skills.

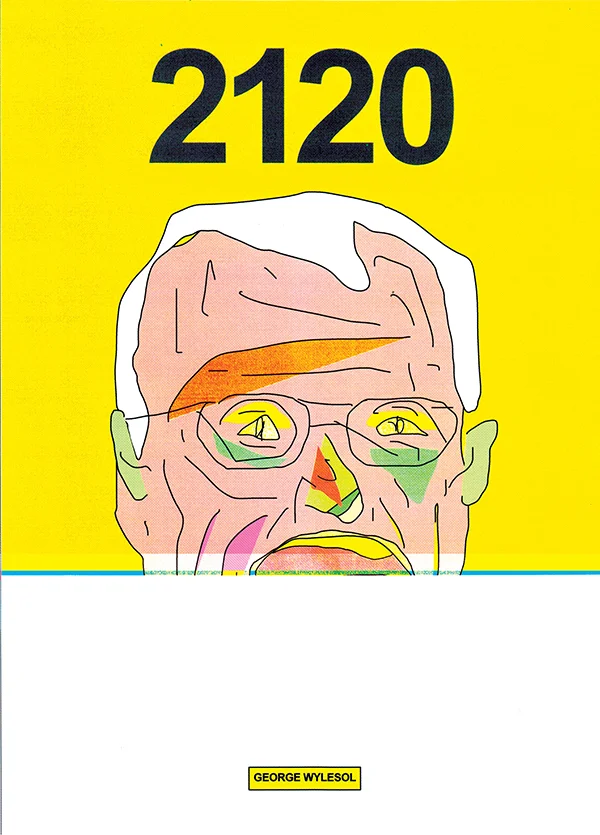

2120 presents us with the same blocky style, this time with more emphasis on geometric shapes which are paired with striking color contrasts. On this occasion, we’re seeing things from the perspective of Wade Duffy, a computer repairman who has arrived at 2120 Macmillan Drive to fix a computer. Not only does the reader see through Wade’s perspective, the reader also directs Wade’s movements. As the front matter informs us, “this is not a linear book”, and we make our way through the subsequent maze of events by choosing which page numbers to follow.

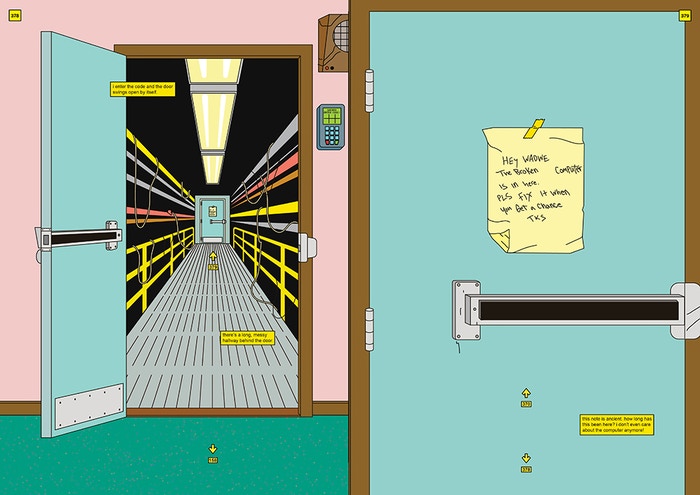

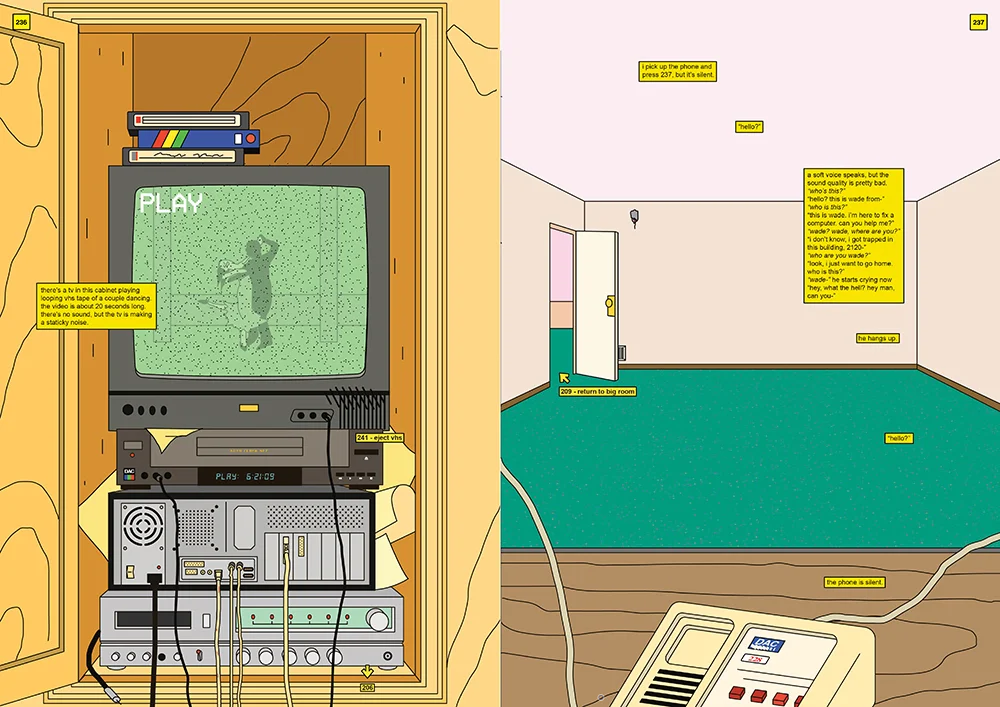

It’s not only a “choose your own adventure” format, however. 2120 also contains interactive elements that mimic early “point-and-click” computer and puzzle games. The interactive elements involve the reader discovering number patterns that can be used at different points to “unlock” doors. Those number patterns double up as the page numbers which direct you to the next part of the story.

The book creates a healthy amount of friction between agency and a lack thereof. At points, the reader can choose to “turn” left or right, but their decision might mean that they’re turning over pages of monotonous hallways. There are also some obvious points of contention when it comes to the possible plot. Upon finding himself (or “you”, depending on your point of view) locked inside the building in the first few pages, a sensible option upon realizing the place is empty would be to break the window and climb out. However, in one of the handful of possible conclusions you can reach, Wylesol does actually play with this lack of agency, turning it into a moment to unsettle the reader by acknowledging them. And to be fair, Wade’s insistence on venturing ever further into the building, which is impossibly big on the inside, is also a typical decision that a protagonist in a horror or thriller-esque scenario would take.

In a recent interview with Broken Frontier, Wylesol discussed the intense amount of notes, scripts, and drafts he put together while creating this book. You can feel that level of detail come through the pages. He also noted that he writes from the first person, and is often uninterested in drawing people, rather preferring to focus on the spaces (physical, imagined, and digital) in which they exist. In this sense, he’s similar to Martin Vaughn-James, who I recently wrote about for this site, and who made comics with a surrealist and psychoanalytical approach to storytelling.

As Wade passes through more doors, hallways, and dead ends, you get a sense that all is not well at 2120 Macmillan Drive. Things have been pulled from sockets, radios leak static, and the place is seemingly deserted. Curiosity gets the better of Wade, and you help him discover a way to get out by exploring as much of the scene as possible. Wade is surprisingly nonplussed when he eventually comes into contact with a few of the building’s remaining and strange characters. We also stumble across some abstract figures that can best be described as pitch-black flames.

The book’s interactive elements aren’t always clear. Some tips here and there that gesture towards what combinations are useful to note, or where a combination might be found (rather than the standard “I don’t know the code” that Wade offers) would be useful. I appreciate Wylesol’s dedication to creating mystery and encouraging effort from the reader, but there are moments when I had to cheat and reverse engineer a particular direction of the plot to figure out where the number combination could be found. There are a couple of necessary steps I still haven’t got my head around. Then again, I was always pretty bad at video games. Perhaps Wylesol could supply us useless readers with a walkthrough? In any case, I advise you to have pen and paper ready before you embark on this journey.

One reviewer mentions that they first read through it without making any decisions, and it is worth remembering to just sit with and appreciate Wyslesol’s often arresting and sometimes unsettling spreads. With a flair for simplicity, Wylesol has a unique ability to create a strange and alluring world. One way he does this is by employing off-center perspectives that accentuate an exaggerated sense of space that result in 2120 having a woozy and somewhat alien atmosphere.

I count a total of three possible “final pages” (aside from a handful of moments where panels are used to stagger the sense of time passing, the whole book is told in either splash pages or double-page spreads). Many of the concluding moments bring you to the same one. This is often after you’ve decided to let Wade interact in his environment in some way that creates a glitch in the system. If you keep following these paths you create an infinity loop that brings Wade right back to where he started.

There’s one particular thread, the longest in the book, that reveals the nature of the life Wade is living, and results in a breaking-the-fourth-wall moment that acts as a playful reference to the reader, and finally lets you close the book. Scholars interested in the relationship between reader, text, agency, and interpretation will have a lot to pick apart here. Thankfully, Wylesol embeds these theoretically heavy moments with dark humor and visual playfulness.

Aside from my frustrations with the book’s mechanics, 2120 reinforces my opinion that Wylesol is one of the most creative comics artists out there. He has a unique ability to produce an uncanny recreation of early computer aesthetics, filtered through an illustrator’s eye for attractive designs and a cartoonist’s interest in reducing things to their most essential elements in order to heighten their effectiveness at communicating feeling and/or how they are experienced. That combination results in work that is one part uncomfortable and another part totally engaging. In even attempting to pull off the sort of narrative trickery that he’s employed both here and in his previous book, Wylesol showcases the expanse of possibilities that comics as a narrative medium has but rarely tackles.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply