How still is a star? From a distance, it seems an unmoving spot in the sky, a constant of the night sky. But it is in flux, it oscillates and turns and pulses in ways only noticeable from a nearer perspective. Something far away can erupt with motion while remaining motionless from our view. Is stillness, then, even possible? Or is stillness just an illusion of distance?

The first two parts in Quiet Thoughts, a new collection of poetry comics by Karen Shangguan from Avery Hill, are from the perspectives of a star and a goldfish, respectively, and both ask questions of stillness and perspective. Through shifting scale, Shangguan finds similar (e)motion in the smallest and largest of things. The book’s opening text (just before we move into the thoughts of a star), in pale handwritten text, barely visible against the background, Shangguan writes of a “natural poetry in stillness/in the same way dreams form meaning without words.” before finishing the opening with a language of movement, “splaying across ice and waters/traveling through different eyes/form quiet thoughts.”

Stillness becomes movement in order to express the quiet thoughts of the book’s name. This is a fundamental dialectic of comics pointed out by Kim Jooha in a 2019 piece for The Comics Journal, “The comics reader produces continuity out of discontinuity; movement and time out of stillness.” Comics disguise movement as stillness, a static page of art cannot literally contain any movement, but it can feel like it does, it can show how movement works and what movement does. That’s the whole job of comics.

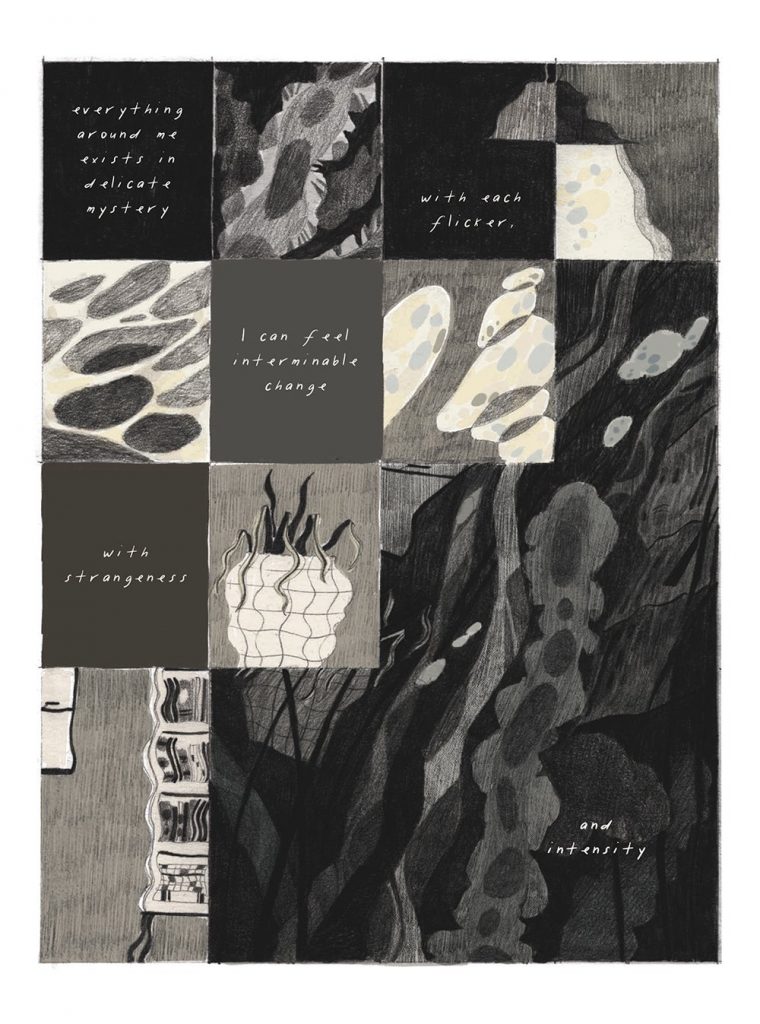

In Quiet Thoughts, Shangguan points directly to this formal dichotomy. Throughout the book, she moves through different scales and perspectives, changing her artistic style, finding ways to reconcile movement with stillness from different angles. When she is a star, panels showing malformed segments of planetary bodies float on the page, seemingly disconnected from each other. It creates a sense that everything here is happening all at once. The stillness of this vast spread of space isn’t in its lack of movement, rather all the movement that can happen is happening, so there is nowhere else left to move, leaving an impression of stillness.

Likewise, when she writes about cities or fish, Shangguan layers images, packing panels more tightly, she packs glimpses of life into systems of grids. The goldfish that arrives second in the book, after the star, is seen through a grid with delicate borders that fills half the page, stemming from one corner, leaving the other corner muddy liquid. We’re offered snapshots of undersea life. Like the massive objects in space, in the packed panels you can’t see the whole bodies of these tiny fish.

Later, in a section titled ‘The Tactality of Sounds,’ long and thin and overlapping panels feature vague spots of pale yellow light and dark grey shadows. The text overlaid in hard to read places is mostly onomatopoeia, “kshhhssshhhhhh,’ ‘vvvvvvvvrrrr,” with a few fragments of sentences about city life, “…most cities are like that…/…none of them like san fran…” Before ending with one big panel where the light and shadow swirl together and the text moves down into the white space, captioning the single big panel instead of occupying the same space. After an initial cacophony, where the meanings of text, image, and sound blocked each other from being heard, a shift in the perspective can adjust and separate image from sound and text. Chaos becomes organized calm; clarity moves it into stillness.

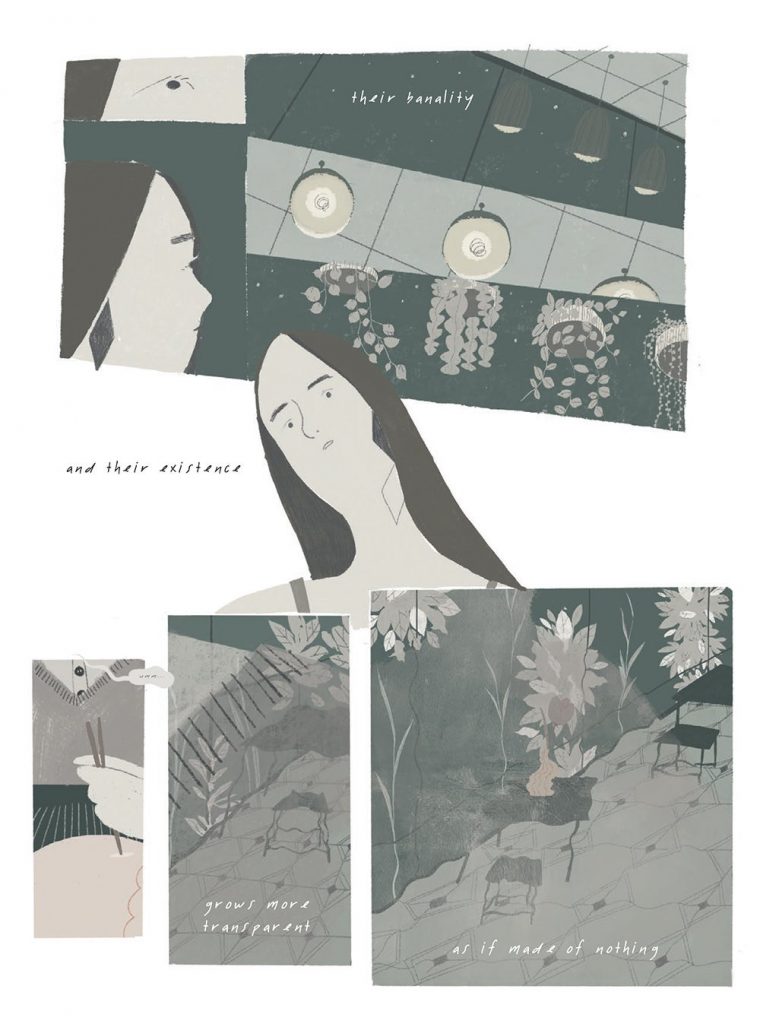

That stillness comes from structure, just like the fish in their heavily paneled pages. Structure gives security, a sense that there are certain constants to the world. When Shangguan transitions between the sections of Quiet Thoughts, she generally zooms out from the subject of that section to reveal a person, a number of these are swimming, some are playing instruments. A few times these transitory people will expand into their own sections, with these poems being more melancholy, about insecure people longing for each other. While sometimes the words of these can be a little on the nose and saccharine, Shangguan’s renderings of people add a wrinkle to the ideas of perspective, stillness, and movement.

Her people, when the focus of a section, unlike the subjects of other parts of the book, are seen in full. They are unobscured and complete. Their boundaries are clear in a way that is unseen elsewhere in the book. Shangguan draws them in a more traditionally representative style, existing within panels laid out to look more like a narrative comic. But despite the more solid depictions, Shangguan’s people are trapped inside these panels and representations. They are more clearly boundaried than most subjects of the book, but that splits them off from the rest of what’s around them. Their perspectives and scales are limited in a way that the more fluid and obscured things aren’t.

And that’s what makes them insecure; they are stuck in themselves, aware of, but separate to, the vastness around them. The swimmers drift through endless water, contained in uncontained space. Compared to what surrounds them, their movements become small, almost insignificant. They get lost at sea. People sit at an in-between scale. The goldfish is too small to be taken in individually, the star too big to absorb all at once, they have to be read as systems that break them up into parts, make their mass movements appear still. But Shangguan’s people don’t fit into those systems. They’re complete but unsettled.

But that’s what’s needed to understand the things that are too big to see their movement. We understand the movements of a person, it allows us to contextualize the movements of the things that are too massive or too small to see move. Things that appear still from afar are actually full of the same kind of tumult as the things we see thrashing around near us. Stillness is an illusion of scale. Nothing is unmoving.

If stillness breeds a ‘natural poetry’ as Shangguan’s opening text claims, then that poetry can be of everything, because stillness is solely a matter of perspective. In Quiet Thoughts, Shangguan looks for that poetry. Using seemingly static comics panels, she finds motion and meaning in boundless stillness.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply