Behind their classically laid-out, commercially styled covers (complete with old-school colophons to tickle the collector’s fancy), the first two issues of Tom Kaczynski’s Cartoon Dialectics reveal equally traditionalist layouts. Regular six-panel beats are interrupted occasionally by bleeds or full-width panels, not slavishly aligned to the ground-pulse of the narrative (or discourse), but cutting across it polyrhythmically to elicit changing patterns of visual and semantic emphasis. Comics artists sometimes have as much in common with drummers as they do with writers.

Aside from a few pages of text, this prototypical approach to layout isn’t interrupted in the interests of either formal experiment or narrative action. Everything that’s present in these comics is constrained within this disciplined formal frame and a simple three-color palette — with half-tones as a reminder of the medium’s technological heritage. Formally, the books are entirely shaped by the industrial practices of commercial comics — their design is a consequence of the divisions of labour, printing technologies, and market forces that shaped American comics in the Golden and Silver Ages. But of course, it isn’t possible to simply empty an old comic of its content and fill it up with something else. “The medium is the message,” as Marshall McLuhan pointed out: form is not separable from content. These books are ironic simulacra.

That irony begins in the aforementioned colophon, where the cover price is listed as the “accursed share”. This is a term of George Bataille’s for an economic excess (in contrast to a productive surplus) which, according to him, must be expended on luxury or public spectacle without hope of return — if it isn’t to fester and burst out to expend itself catastrophically in war or some other disaster. By deploying this term, Kaczynski positions his comics alongside the unnecessary luxuries, sacrificial offerings, and ritual practices that Bataille had in mind, but he also stakes a claim for its ethical necessity. If we don’t buy his comic our surplus economic product will “go bad”, and come back to bite us in the ass!

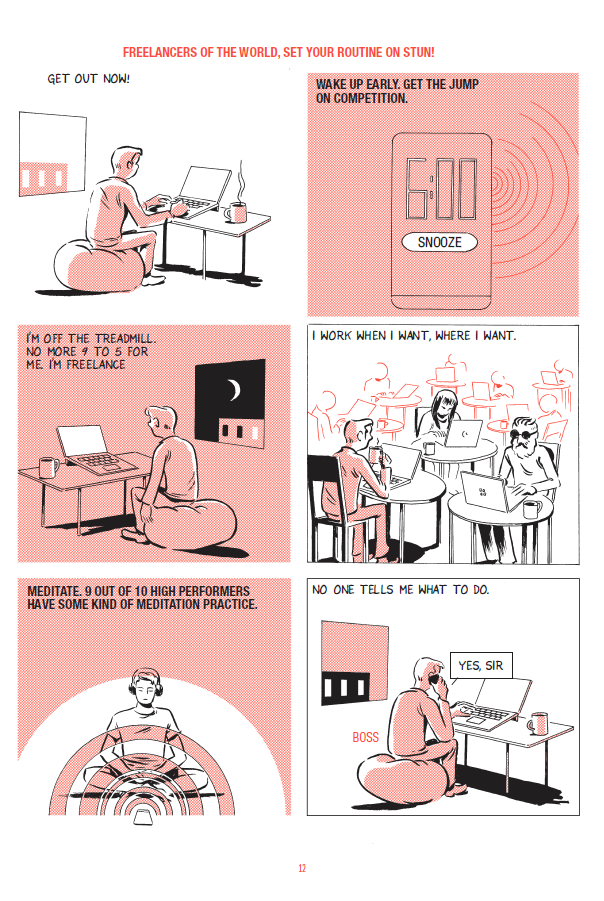

As soon as we open the first issue of Cartoon Dialectics, we are presented with “Negative intuitions”, a five-page graphic essay outlining Jean Baudrillard’s notion that we live in a “state of simulation”, condemned to imitate the formal schema of past utopias. This is a recurring theme for Kaczynski: the consumerist dystopia we inhabit today has the outward appearance of historical science-fiction utopias. The comic book I am reading has the appearance of the socially confirmatory superhero rag that used to reassure me that powerful individuals will, by and large, do the right thing; and yet it is full of awkward, critical doubts, serving only to undermine my faith in that social order. It is a simulacrum, a sign that points not to another, “real” comic book, but to another simulacrum, itself a mock-up that also pointed to nothing solid, in an infinite regression to nowhere.

Sounds fun, right? A comic book full of philosophical discussions and arch references to obscure critical theorists. Well, if you’re going to do philosophy in print, you might as well do it in sequential art as in prose — Logicomix by Apostolos Doxiadis and Christos Papadimitriou taught me a lot more about the thinking of Bertrand Russell than I’d ever have bothered to discover from another medium — but that’s not what this is. Actually, it is a lot of fun. Kaczynski means what he says about utopias, about the ideological mythology of labour, about ecology, about Heidegger’s distinction between presence and readiness-to-hand, but the purely discursive passages in these two issues are relatively brief, and the larger part of them is taken up by narrative — satirical, thought-provoking, funny, and intelligent stories, that make entertaining connections between, say, kung-fu movies and workplace politics.

The text passages are tongue-in-cheek, but still make some kind of sense — especially the argument in issue 2 for comics as the pre-eminent medium for intellectual work (if I could draw I might just take that on board!) — and point in some interesting directions. Kaczynski likes to refer to his work as ‘komicxs’, maybe in an attempt at one-upmanship with the underground comix of the 1960s and 70s, and he provides an account of the origin of the term in a tale of Polish writers between the world wars. Apparently, Bruno Schulz’s legendary lost work, The Messiah, was the foundational work in the medium of komicx, and given its stubborn resistance to discovery, who’s to gainsay him? Witkacy, a friend of Schulz’s and one of the writers featured in this tale, crops up again in a one-page “Eschatological book club”, alongside Ignatious Donnelly, Michel Houllebecq, and J.G. Ballard.

Both issues of Cartoon Dialectics are pretty dense, in terms of the large number of ideas and references that Kaczynski manages to include in very few pages, but they don’t feel overly heavy. To be honest, ideas are mostly touched upon, or deposited, without being explored in exhaustive detail. What that leaves us with (in concert with the ‘komicx’ origin story and the ‘book club’) is a curated set of interests. Cartoon Dialectics comes across to me as a kind of “museum of Tom Kaczynski”, where the thinkers and writers that have crossed his path find a common life. I haven’t really encountered another comic like it, but it put me in mind of the early books of Iain Sinclair, an English psychogeographer who is best known in the comics world for his influence on (and friendship with) Alan Moore. Kaczynski’s work is by no means as confusing as Sinclair’s, and his interests are different, but they are mashed up into publications with a similarly insouciant eclecticism.

I don’t mean to imply that Kaczynski can’t or won’t tell a story. Erudite and clever he is, but he doesn’t let that get in the way of making a good comic. Indeed, the majority of the second issue is taken up by a post-apocalyptic picaresque, which is both an entertainment and a continued exploration of the ideas touched upon in the first. Whether it will continue in the third issue, or whether there will be a continuation of the thematic narrative, whether there is any grand plan that is going to weave intellectual and affective threads coherently through a whole run of comics, or whether the entire thing is a more or less random assemblage, remains pleasingly unclear. Kaczynski is a skilled draughtsperson who deploys a loose, scratchy style well-matched to the apparent casualness with which he slaps down a bit of critical theory here, and a bit of alternative history there, and which undercuts the tendency of his subject matter to appear dauntingly intellectual. If he does have something in common with a drummer, as I suggested at the outset, then it’s a “different” drummer whose beat he invites us to march to. Kaczynski takes us on a playful jaunt through some odd corners of his own brain, and I can think of far worse places to spend an afternoon.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply