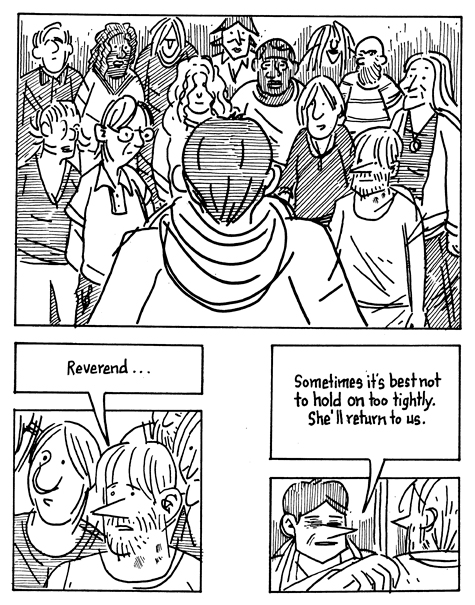

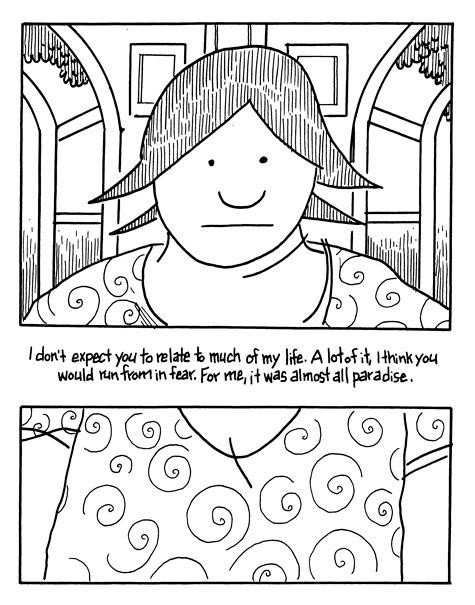

Ostensibly an updated take on the Jonestown massacre for the social media age, cartoonist Will Dinski’s Holy Hannah (Uncivilized Book, 2019) centers on two characters, app developer Hannah Watt and professional confidence man Noah Ganapathy, and their relationships with and to one Rev. Carpenter, the book’s thinly-veiled Jim Jones stand-in. Hannah’s a thirty-something (I think) recluse who is privileged enough to ensconce herself in her apartment and avoid contact with a public she disdains (or was, until she pissed away the fortune she made in tech biz), while Noah gave up a successful career in the corporate world for the “good” Reverend — if you’re familiar with the actual history of Jonestown, you may already be starting to see the problem here.

If not, let me spell it out for you — Jim Jones recruited his followers from the ranks of the socially, culturally, and economically dispossessed. He preyed upon the marginalized and the vulnerable. The population of Jonestown was over 70% black and majority-female. And this wasn’t by accident, it was by design. Unless you choose to take the view that it’s all just some bizarre coincidence that all of Jones’ top lieutenants, as well as his armed “security” retinue, were white.

There’s precisely one black cult member in Carpenter’s flock — a good-hearted but hapless sort literally named Cletus — and therefore the twisted racial dynamic that was at the heart of Jones’ operation is either something with which Dinski was unfamiliar (five minutes of research would have taken care of that problem), or something he chose to deliberately dispense with. The former is sloppy, but forgivable — the latter borders on the insidious.

And unfortunately, evidence on offer in the book itself points toward the latter and I believe Dinski has done his homework. For instance, he’s clearly familiar with the key role Jones and Peoples Temple played in the election of San Francisco mayor George Moscone — a Minneapolis mayoral candidate in Holy Hannah wins by 300 votes with Carpenter’s help and, like his real-life counterpart, he’s also put in charge of the city Public Housing Authority. What’s missing, however, is Carpenter using that position to swell the ranks of his cult, which is precisely what Jones did, placing members of his flock in key positions within the agency he headed up in order to recruit more poor people of color into his “church.”

All of this is just prelude to the book’s central problem, though, which is that Dinski uses his narrative to reinforce the increasingly-discredited notion of Jonestown being a “mass suicide” situation rather than the mass murder it looks to have been. In recent years, this idea has bubbled up from the fever swamps of the “conspiracy” underground into the mainstream, thanks largely in part to the efforts of survivor Tim Reiterman and his book Raven, and it’s central to the thesis offered by the award-winning documentary film Jonestown: The Life And Death Of Peoples Temple, as well as the “docu-drama” Jonestown: Paradise Lost. I’m not ready to fully embrace the notion advanced by legendary “conspiracy” researchers such as John Judge and Mae Brussell that the entire cult was an offshoot of the CIA’s notorious MK-ULTRA program — although there’s plenty of evidence, both concrete and circumstantial, to lend support to that idea — but as I sifted through many of the details and accounts from all quarters in preparation for writing this review, there was absolutely no escaping the conclusion that what happened in the jungles of Guyana was in no way a “suicide.” Most of the bodies of the dead had injection marks between the neck and shoulder. The others bore signs of being shot or strangled. Not one of them had the cyanide rictus “death grin” associated with the type of poisoning that is said to have occurred. But don’t take my word for it — ask Dr. Mootoo, the Guyanese pathologist who was first on the scene and in charge of his country’s official investigation. It was only when the Americans arrived — and the number of dead shot up drastically — that the idea that everyone down there had killed themselves took root as the official narrative.

Again, Reiterman has been pushing back on that notion vigorously in recent years, maintaining that even those who “drank the Kool-Aid” did so because the camp was surrounded by armed white guards who were going to kill everybody one way or the other, but defenders of the company line needn’t fear: a cartoonist is here to contradict the eyewitness testimony of someone who was only, ya know, actually there. It’s his prerogative to do so, of course, this being a work of “reality-based” fiction, but I have to wonder how socially and historically responsible such a decision is in light of the facts and information about the tragedy which contradict earlier media narratives that have emerged. Simply put, racism and sexism are central to the actual events of the tragedy, and ignoring them completely is rather akin to the decision made by the producers of the film Cold Mountain to tell a Civil War story based in the South that makes no mention of slavery.

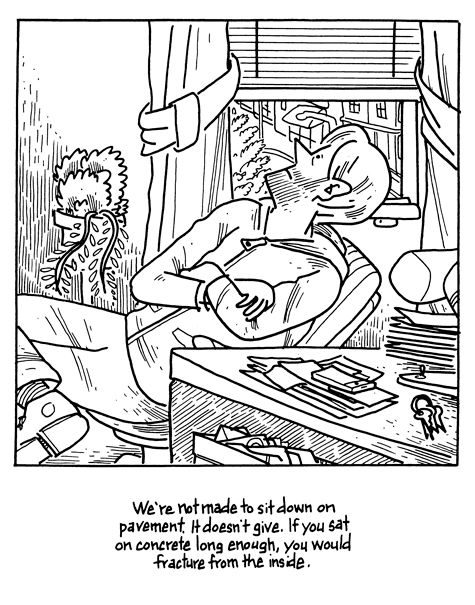

I’ve got some problems with this book on a purely technical level as well — Dinski’s cartooning, while admittedly crisp and emotionally resonant in its understatedness, is pretty limited in terms of what it can practically accomplish, as the laughably absurd “fight” between Hannah and one of the media members who visits Carpenter’s camp demonstrates (there’s no Leo Ryan doppelganger in this story, rather it’s the press who is “blowing the whistle” — an unforgivable slight to the only member of congress to die in the line of duty). In Holy Hannah, Carpenter’s motivation for fleeing the country is pretty weak, based as it is solely on one newspaper article accusing him of being a profiteer rather than linking him to the unexplained deaths of former cult members as New West magazine did in regards to Jones; the cult members gong around town to collect every single copy of said newspaper before people see the unflattering write-up isn’t just absurd, it’s quite literally impossible; the list goes on.

In all honesty, the whole thing is just a confused project, even if Dinski does come up with a novel quasi-explanation for how the gun that killed Jones/Carptenter was found so far from the body despite that, too, supposedly being another “suicide.” If he takes exception to the idea that Jonestown was anything other the “mass suicide” the public has always been told it is, he never makes it clear why. If he’s unaware of the historical re-evaluation that’s been taking place, it’s more than a little sloppy. And if his goal is simply to re-cast the story in a contemporary context, he never makes much of a case for why now is a vital and necessary time to do so, nor does his narrative ever progress much beyond a “ripped from the headlines”-style television “docu-drama.”

Say what you will for the notion of “drinking the Kool-Aid” that’s grimly found its way into the popular lexicon — in this critic’s view, Holy Hannah is actually serving it up.

Disclosure: the author of this review has also written a comic strip entitled Walk A Mile In My Shoes : A Jonestown History, to be published in Robyn Chapman’s forthcoming American Cult anthology with art by Mike Freiheit, that offers a very different perspective on the Jonestown tragedy.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply