Contemporary creative work that functions as metacommentary on the purpose of making and valuing art has only been complicated by the internet’s tendency – and capitalist imperative – to organize around the highly mediated, commodified self. This avatar, a product of the universal self-delusion that we are all the virtuous heroes of our own well-curated stories, has never before cleaved closer to the egoistic myth of the tortured creative genius that Kelsey Wroten examines with nuance in her first full-length graphic novel, Cannonball. Cannonball investigates the ascent of queer art student-cum-YA author Caroline Bertram, for whom the self-delusive creative imperative to both conceal and mine the depths of the authentic and imperfect self results in the familiar, contradictory millennial stasis: namely, a state consisting simultaneously of both frantic, ceaseless movement and an inability to advance beyond a fixed point.

In Cannonball, the reader meets Caroline on the cusp of so-called real adulthood, graduating from art school and moving out of her parent’s house. Caroline is a fatalist who sees herself, and indeed human endeavor in general, as cursed, which tells you about all you need to know about her level of self-absorption. It’s not just that unfair or bad things happen to her, it’s that they are intentionally selected and individually enacted upon her by a conscious and vindictive universe. Similarly, for Caroline, great art depends not on factors within the creator’s control, but on divine providence, which enters Caroline’s life in the form of the titular Cannonball, a wrestler upon whom Caroline models her aspirational, illusive spirit guide and muse.

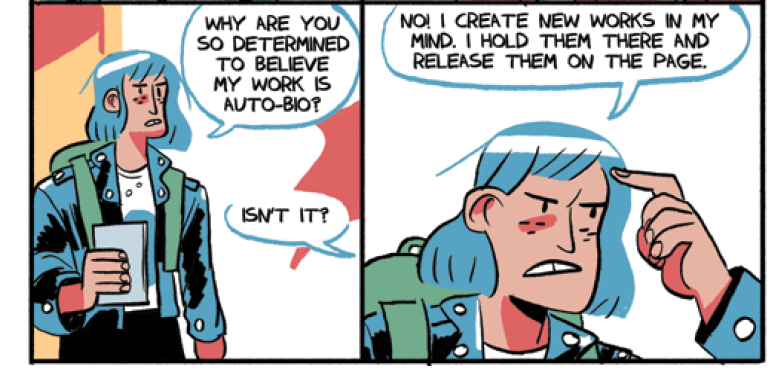

That “Saint Cannonball” is modeled on a wrestler serves as a neat metaphor for Caroline’s relationship to art and self-delusion: costumed wrestling depends on a veneer of realism, a communal agreement to suspend disbelief to enjoy the wrestler’s egocentric hero narrative. Caroline views her writing as an inversion of this ostentatious persona: both genre and overwrought prose are masks she pulls over the mundane details of her life and the lives of her friends which she mines for material, too scared and insecure to make work that is explicitly autobiographical.

Caroline’s fear around artistic vulnerability encompasses her relationships as well. Her difficulty pinning down the answer to the question of what makes successful art extends to her inability to decide what it means to be a successful person. Hurt deeply after being dumped by her first love, Sophie, Caroline sidesteps vulnerability and preempts rejection by asserting herself as brash, cynical, and inviolable. Echoing Saint Cannonball’s masked uniform, Caroline dons, early in the book, a tough-looking leather jacket. “Call me Daddy,” she jokes to her best friend, Penelope, aligning herself, intentionally or not, with the book’s cruel and coercive paternal figures, whose power and imperviousness Caroline hopes to someday appropriate for herself.

Caroline wades into both the moral gray and faux universality of this straight male default by stealing and propagating the seed of a story idea foisted on her by a man coded this way who approaches her in a café, even though she’s wearing headphones, writing, and clearly not receptive to an interruption. Despite Caroline’s obvious disdain for this man, the success she subsequently attains with the story appears initially to validate this inexperienced rando’s confident belief that art’s value lies squarely in its market appeal and potential for material profit. Caroline dismisses his story idea at the outset on the very basis of its ubiquity, that it’s overdone, but goes on to secure financial success and popularity with his “immortal dog and young girl save the world” plot anyway. Her fatalism and her belief in muses assist in her subconscious justification of her theft: Saint Cannonball “reveals” the story to her in a divine dream.

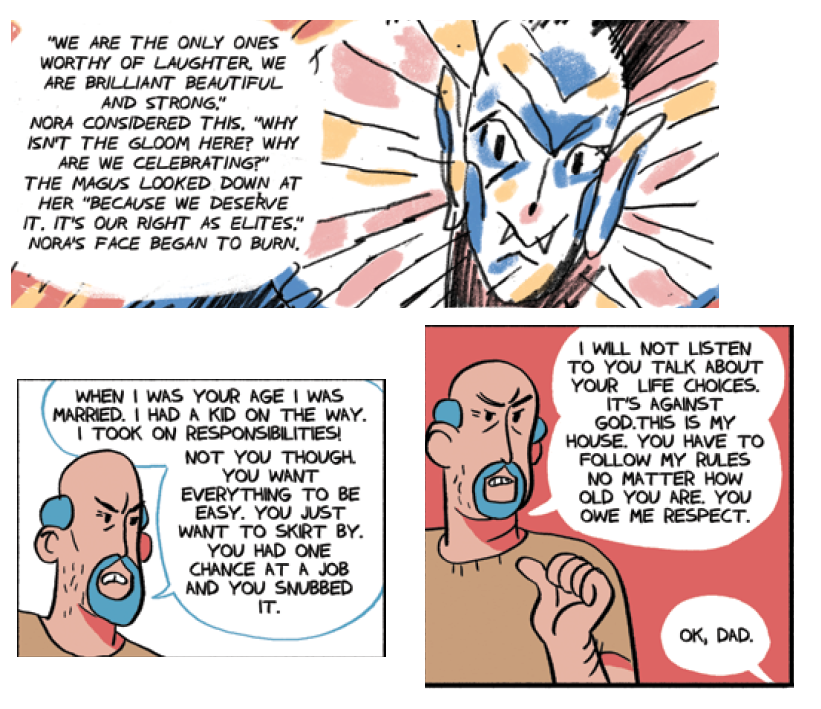

However, in co-opting the power that male figures around her have, under a capitalist system of exploitation designed to be easily invisible to its beneficiaries, Caroline must confront causing the same kinds of pain which she herself has suffered from. Both her homophobic boomer father and the “Magus” villain she creates in her book share a sense of elitist entitlement to what they have, whereas for Caroline, her guilt and imposter syndrome are worse than ever once she’s “successful” on these terms. If she abdicates the responsibility of answering for herself the difficult questions of what is valuable, in life and in art, then she is not, in fact, attaining power at all, but relinquishing it.

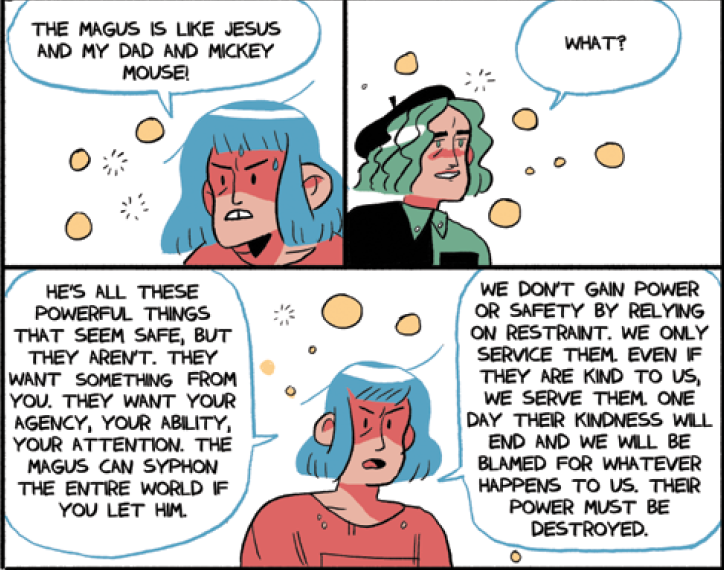

Caroline approaches this realization in a moment of drunken clarity, during an ethically dubious night of intimacy with a young woman assigned to guide her during her book tour – a young woman who clearly admires her and is employed as a resource to her, creating an uncomfortable power dynamic which Caroline takes advantage of. On another narcissistic tirade, Caroline draws a parallel between her father, the Magus, and the most recognizable emblem of creative capitalism and artistic homogeneity: Mickey Mouse.

In the end, however, despite the heights to which Caroline ascends in her career, she recognizes the hollow interior of the adulation directed at her leather-jacket machismo mask instead of the real, fallible her. Caroline’s fans don’t care whether or not she’s built a concealed undercarriage of personal truth beneath the fluff of her young-adult fantasy romp, truth that it’s unlikely they even want. Her hefty royalty checks remain guiltily unopened on a table in her bare apartment, ironically left behind by the thieves who steal her TV. Caroline’s shortcuts – to so-called artistic fulfilment, to intimacy, to making value judgements – have robbed her of any semblance of growth.

The heroine of Caroline’s book, Nora, is able within the realm of fantasy to reject what the Magus offers, where Caroline cannot. She is unable to reconcile the successful avatar she has created for herself with the terms upon which that success is predicated. Caroline’s recurring spirals into self-destruction reflect this ambivalence. The book’s ending crescendos with Caroline confronting Nora in a drunkenly imagined sequel to the first book in her YA series. This interaction bears out Caroline’s disgust for the person she has become when she asks whether Nora trusts her. Go fuck yourself, her heroine responds. Like Sisyphus, Caroline ends Cannonball full circle in the same defeated posture of self-destructive oblivion which she starts, both on the book’s title page, and in the home video of her falling as a toddler in the prologue. As readers, we wonder the same thing her parents do as they witness her trying to walk in this video: What if she never learns?

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply