Reading the collected, translated Maggy Garrisson from SelfMadeHero made me think about how different artists approach genre stories. The book, written by Lewis Trondheim and drawn by Stephane Ory, is a funny & fresh take on the hard-boiled detective genre. The titular character, a young woman in London, takes a job as a private detective’s secretary. Subverting that “girl Friday” trope, she immediately establishes herself as far more clever and competent than he is. She also learns that cleverness won’t help her when she’s dealing with ruthless criminals. Throughout the course of the story, which collects three 48-page albums originally published in France by Dupuis, Maggy encounters all sorts of unlikely allies, untimely betrayals, and the occasionally banal weirdness of the criminal underworld. The plot, clever as it is, is less interesting to me than the storytelling choices Trondheim and Ory make in service to the detective genre.

Trondheim is unusual because he’s the rare artist who draws a lot of his own comics but also frequently collaborates with others. His own style is cartoony and highly expressive and usually features anthropomorphic characters. Gesture and body language are key elements of his work, allowing the audience to connect to his characters. Trondheim started cartooning before he could really draw, and he’s always understood pacing, page design, panel-to-panel transitions, and other cartooning essentials. Trondheim has done gag work, science-fiction, fantasy, autobiography, abstract comics, young adult comics, kids’ comics, and more. When he’s written for other artists, his collaborators have also tended to work in a cartoony style. Maggy Garrisson represents a visual break in his output because its naturalistic rendering is in sharp contrast both to his own work and the work of the vast majority of his collaborators.

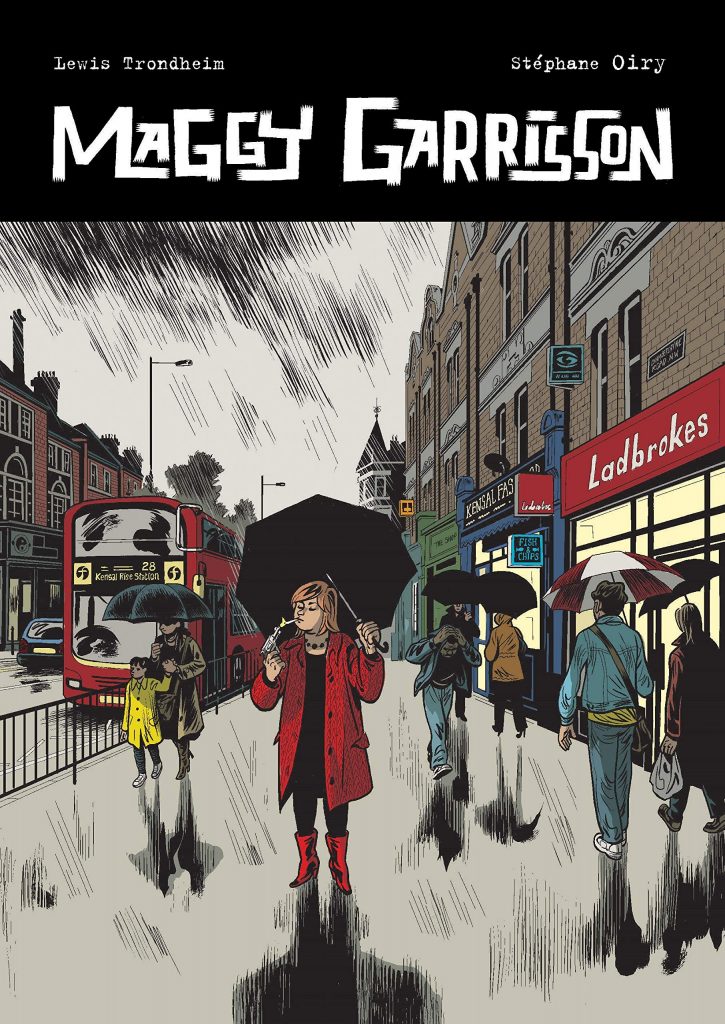

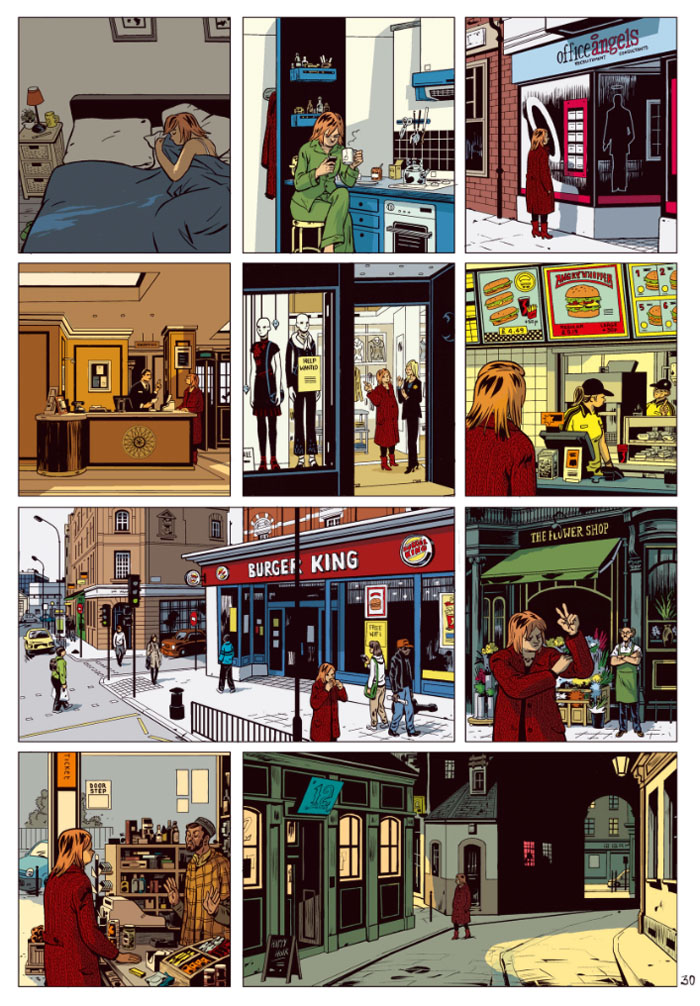

That naturalistic but moody style is akin to the sort of comics Warren Pleece used to draw for Vertigo, or Sean Phillips draws for Image. I’m thinking comics like Deadenders for Pleece and Criminal from Phillips, both of which are written by Ed Brubaker, a connoisseur of pulp fiction. The goal of works like these is to establish mood above all else. The colors are muted, to the point of dullness. Much of the action takes place at night, and daytime scenes often feature rain. Similarly, in Maggy Garrisson, there’s extensive reliance on spotting blacks to convey the general dark, sleazy shabbiness of Maggy’s London. Stephane Ory’s character design is lumpy and slightly grotesque. By instantly establishing an atmosphere that’s familiar to readers of detective or crime comics, Trondheim can lean in on those tropes with ease or else subvert them in funny ways.

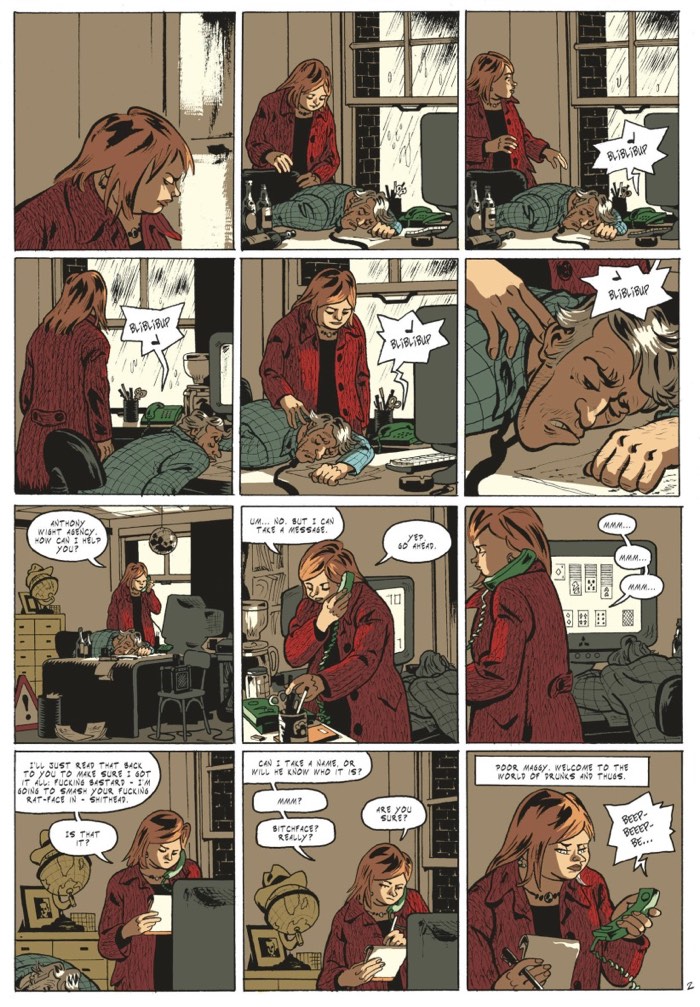

For example, in the first twenty pages, Trondheim establishes Maggy as the protagonist, not the dull detective Wight. In this particular genre, detectives are often written as drunks, but, in this case, Wight’s alcoholism actually makes him a mediocre investigator. Maggy is further established as broke and willing to engage in ethically murky activities, like making some quick money by buying a replacement canary for someone while claiming it was the original. When Wight’s beaten up by a thug, Maggy goes through his desk drawers at his behest and comes across a gun — except it’s really a cigarette lighter that looks like a gun. In classic detective style, Trondheim introduces a MacGuffin (some arcade claim tickets) that people are willing to kill for.

Maggy is constantly bemused at the world she finds herself in, and it’s often played for laughs at how easily she can outsmart the thugs, crooked cops, and other degenerates she encounters. At the same time, she learns that she’s not as smart as she thinks she is, as cops and criminals alike are more than willing to hurt and even kill her to get what they want. Trondheim’s use of humor often distracts the reader from the dully brutal nature of Maggy’s adversaries, but Ory’s art pulls the reader back in every time there’s a new threat or act of violence. Through it all, Maggy wins over the audience with her snarky sense of humor and gives-no-fucks attitude, despite the fact that she’s not exactly a nice person herself. It all goes down smoothly with a Bridget Jones as Phillip Marlowe feel.

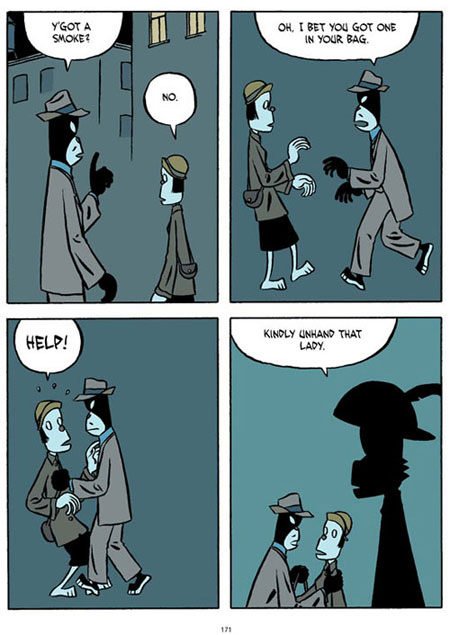

Reading this book brought to mind the comics of the Norwegian cartoonist Jason. Similar to Trondheim, he uses a deadpan, anthropomorphic style for all of his comics. It’s not because he’s limited as a draftsman; indeed, his earliest comics are done in a perfectly-acceptable naturalistic style. Jason simply likes drawing his odd dog and cat people, using that style for every kind of genre. Like Trondheim, he’s taken on every genre imaginable, including pulpy detective stories. For Jason, this consistency of style is his personal stamp on all of his art, giving it an unmistakable feel. The genre is less important than understanding that this is art made on his own terms. It doesn’t matter if it’s a fantasy comic or a series of gag strips, because it’s all Jason–take it or leave it. He has a publisher in Fantagraphics who will publish whatever he feels like and an audience that he’s cultivated–not just because of the art, but because of that absurdist but dry tone. Wider commercial considerations are not his focus.

While Trondheim’s wit and capacity for clever, convoluted plots translate across genres and collaborators, his aim is different from Jason’s. Trondheim is playing to a different audience, depending on the publisher he’s working with. Maggy Garrisson is commercial work, different from the more experimental and personal comics he publishes through his L’Association collective. What does the story gain from having Ory draw it instead of Trondheim? I would say, nothing. It’s easier and more intuitive to read, as the aforementioned visual cues do a lot of the labor ahead of time for the average reader. But being easier to read doesn’t make it more interesting or worthwhile, however.

A version of Maggy Garrison in Trondheim’s own hand would have been every bit as compelling, and perhaps more so, as the reader would have been asked to do a little more work in order to figure out what kind of story this is. A mainstream French publisher like Dupuis isn’t interested in confusing or challenging the reader; instead, they want to draw the reader in as quickly as possible. Trondheim and Ory accomplish this dumbing-down immediately, setting the comedic tone within a familiar visual style. They provide twists and turns that are subversive at times, but ultimately still entirely within the bounds of pulp fiction. Maggy Garrisson is a rollicking bit of enjoyable fluff, but that’s all it is. The result shows the artistic limitations of commercialized entertainment.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply