It’s plenty interesting to read something legitimately — well, interesting — but the task of a biographer entails something more than simply taking a stake of a life that, let’s face it, wouldn’t be written about at all if it weren’t at least somewhat fascinating in the first place. And, certainly, the life of George Orwell (or, as his birth certificate would have it, Eric Blair) is about as rich and complex a subject for biography as anyone. I mean, we’re talking about a guy who in many respects was the “original ANTIFA,” after all, and whose writings, travels, and insights are the stuff of modern legend. Getting readers to turn the pages of his life’s story in a graphic novel should be an easy enough task for any reasonably competent comics creator. What’s trickier, though, is to give us a real understanding of what made the man tick.

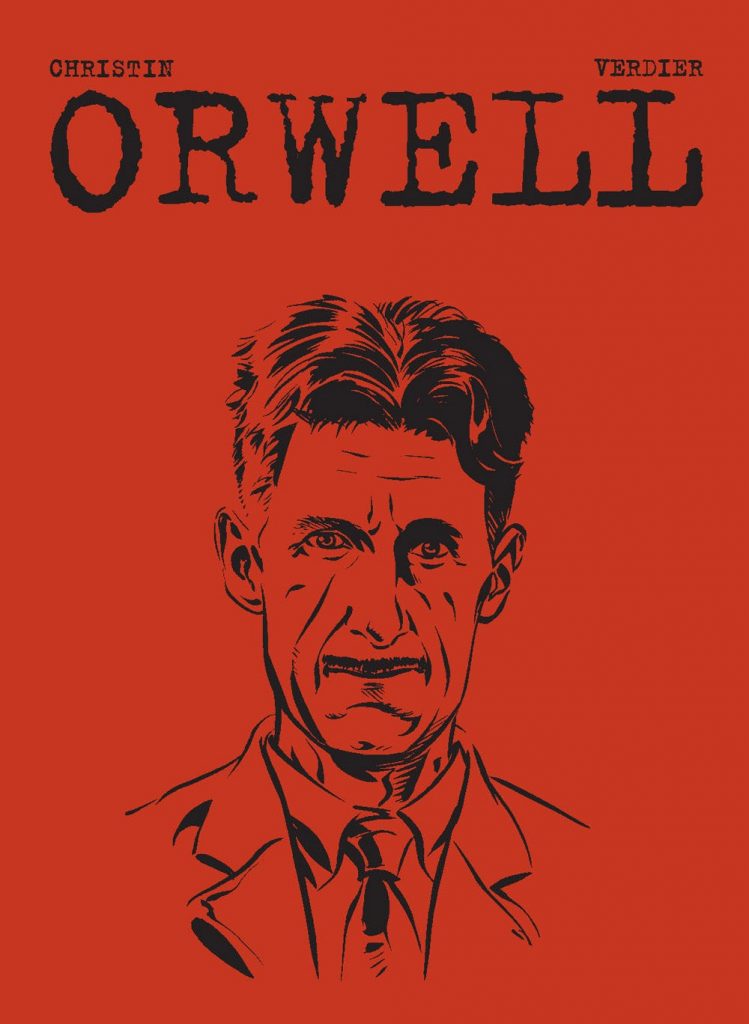

To that end, writer Pierre Christin (of Valerian renown) and artist Sebastien Verdier certainly give it what very much would appear to be their best shot with Orwell (originally published by Dargaud in France in 2019 and newly available in English from SelfMadeHero with translation by Edward Gauvin), but the end result is something of a mixed bag. Certainly, their admiration for their subject is never in question, nor is their level of expertise, but that very admiration and expertise results in a book that hems and haws between a dry factual retelling on the one hand and a hagiographic elegy on the other.

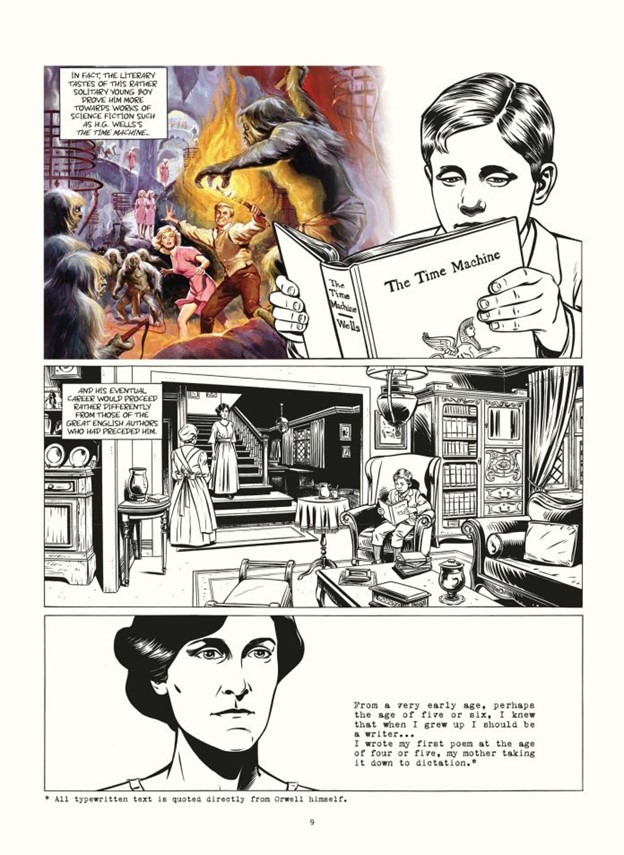

Which is kind of a bummer to say, because their hearts are pretty clearly in the right place with this entire endeavor, and, in some respects, it’s a considerably more innovative work than many a comics biography. Chief among these notable creative flourishes would have to be the decision for Verdier — whose fine, precise art is rich in period detail and flat-out clinical in terms of its veracity — to step aside in favor of a veritable “who’s who” of international comics masters when Christin’s script calls for pages of Orwell’s work to be quoted from and visually represented. Andre Juillard, Olivier Balez, Manu Larcenet, Enki Bilal, Juanjo Guarnido, and the legendary Blutch (with colors from Isabelle Merlet) all turn in superb “pinch-hitting” work in these instances, and the variety they bring to the table — as well as the book’s judicious use of spot colors and photographic reference materials — lends a jolt to the proceedings that is quite welcome. It’s the fact that the book does, in fact, require the occasional jolt that’s the problem here.

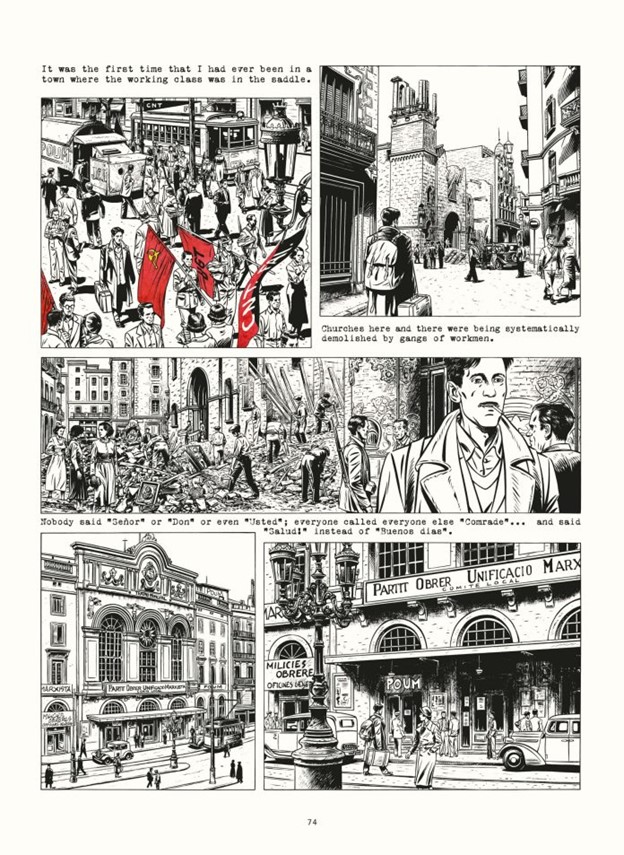

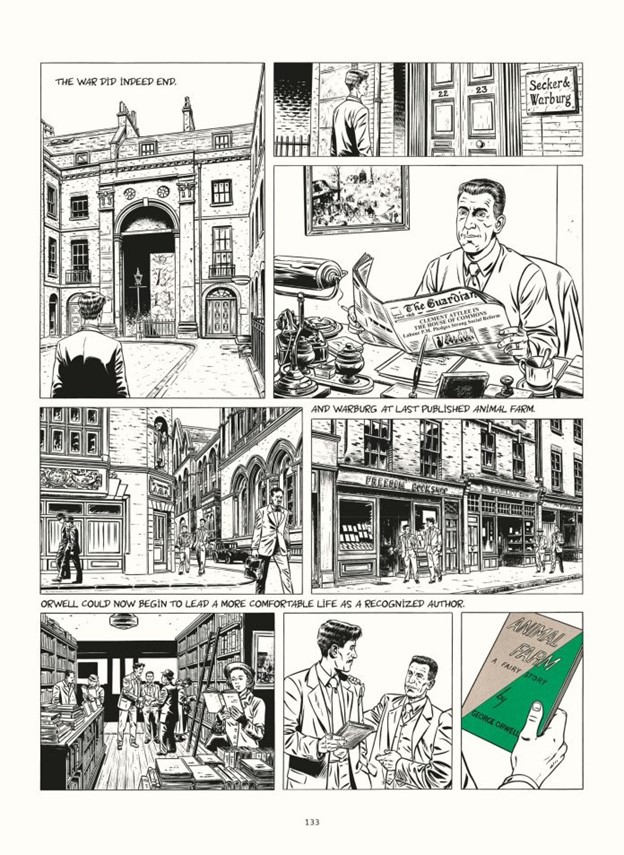

I’m not prepared to apportion any of the responsibility for this on Verdier, really — his art is pitch-perfect for a project of this nature, which relies much more on technical proficiency for its efficacy than it does actual creative inspiration. He’s done his homework and done it well, just as the job requires, and his faces, in particular, are a real joy to spend time looking at. He approaches his work with a journalist’s eye for detail and that’s as it should be given that Orwell was, of course, a journalist himself (among other things). Verdier’s art belies all the well-honed experience of a true craftsman, someone who takes pride in their efforts, and there’s no reason at all why he shouldn’t.

The issues with this book lie, then — as you’ve no doubt guessed — with the script. When Christin hones in on the connections between Orwell’s own life and his writing, the results are terrific and go the extra mile toward putting us not just in the man’s shoes, but inside his head. Unfortunately, there’s less of that than there is of rote factual re-tellings of his life and times, and, while that’s involving enough for readers such as myself who are hardly Orwell experts, there are plenty of well-written biographical sketches of him online that do much the same thing. In a roundabout way, it’s actually to Christin’s credit that his writing is good enough to make us want more than the “nuts and bolts” he frequently confines himself to, but it’s ultimately more than a bit frustrating to see him settle for that when he makes it clear often enough that he’s capable of much more.

Still, at the very least those nuts and bolts are the basis of one hell of a story — I mean, any way you slice it, Orwell’s life was a unique one. Not too many people spent time sleeping in London’s slums, fighting in the Spanish Civil War, and serving in the Burmese police. He got around and developed a worldview that can probably only come from such a wealth of experiences. What’s downright bizarre, though, is to see Christin try to shoehorn that expertly-articulated worldview into something very much akin to establishment centrism in the “After Orwell” epilogue, where he takes both “The Far Left and the Far Right” to task for “shamelessly conscript(ing)” Orwell’s ideas — and even his terminology — to their own ends. The author of 1984 and Animal Farm as a neoliberal moderate? Somehow I find that rather hard to believe, and the case Christin makes for it is a fairly shallow one. It’s couched in respect bordering on reverence, to be sure, and is interesting enough to consider, but it’s no more compelling for that fact — and that’s actually a pretty fair summation of the book as a whole. As a visual “Cliffs Notes” it works fine, but it aspires — maybe even deserves — to be more, and only occasionally achieves its loftier aims.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply