By all rights, I should dislike Mickey’s Craziest Adventure and Donald’s Happiest Adventure by the creative team of Trondheim (words) and Keramidas (pictures). The two albums (henceforth – ‘The Disney Duology’) are short hardcovers in what we think of as the standard Franco-Belgian format and are published in English by IDW and Fantagraphics respectively. These are objects deeply seethed in nostalgia. As one of many who grew up on American superhero comics only to (mostly) renounce them, I am highly suspicious of all objects that seem to exist to remind people of charmed childhood memories. And yet, something about these books hit differently than your average cape-comics homage act…

For the uninitiated: The high-concept (gimmick) of the two albums is that chancing upon a garage sale the two comics luminaries happen to find a bunch of foreign Disney comics magazines that contain a previously uncollected serial, an adventure story told in single pages. Our “creators” are thus presented more as curators – collecting, translating, and publishing the works for the first time. In the case of Mickey’s Craziest Adventure (the first album published), there is a further gimmick: the creators couldn’t find a full run of the serial.

Thus, the story would occasionally jump forward from one event to another, representing the missing pages, bringing to mind the fragmented structure of the Satyricon; or, perhaps better said – Blutch’s Peppulum. Of course, the fragmentation in Blutch is intentional while Petronius’ Satyricon was written as a whole piece, with bits and pieces lost to history. Not that it matters now, for today the literary value of Satyricon is exactly as broken pieces (Finding the complete work is probably of immense historical value, but does not add to the literary merit of the work). The joy of reading it is the unexpected jumps that give the lives of the characters an even wilder edge than implied by the plot. The gaps are now accepted as part of the text (Assuming you accept Coleridge’s ‘Person from Porlock’ story – we don’t need to see a longer version “Kubla Khan.” We might want to see it, but nothing we can find would never rise to level of expectations). Blutch’s take makes it the central theme, life in a vast empire as a series of events seemingly beyond mortal control.

These collections aren’t meant to simply evoke old stories but the sensation of reading them: the pages are presented as occasionally torn and splashed with stains. The fragmentation of the plot brings to mind the pre-internet age in which you read what comics you could find, in what order you could find them, and you could often only guess at what happened in the chapters you missed. Trondheim and Keramidas are not giving you a modern take on an old story (for that, you should go for Regis Loisel’s Mickey Mouse: Zombie Coffee), they are trying to give you the impression of childhood. A comics mathematically designed to encourage Proust-like flashbacks.

American superhero comics, at least when I stopped following them, seemed so stepped in remixing and recreating the past, that they renounced every chance of living in the present (nevermind looking for the future). Every story seemed built on bringing back something from the past, an old concept, an old character, an old event, as a sort of natural building block. As if the only thing that could give these stories value is their relationship to the past of the genre, which quickly became the present as well. Time, in superhero comics, is not merely a flat circle – it is a very narrow one as well. Nothing exists outside the predetermined borders of the genre. Either forward or to the sides. A closed loop, circling the drain.

I should point out, superhero comics are not unique in that manner. This is merely the extreme version of a trend that goes to the very foundations of the comics medium. Read through Thierry Smolderen’s The Origins of Comics: “When American newspapers began publishing humoristic cartoons in the 1890s, that attitude became a major factor in ruthless circulation wars between rival papers and fueled the rapid evolution of the genre. From then on, comic artists began to work according to the most basic principles of the fairground—by following the blind Darwinian rules of attraction.” Nostalgia, as Smolderen claims, was a built-in factor, comics was designed as a habit-forming medium. Something you can come back to every day, knowing things will be more or less the same, in the very newspaper that showed you how chaotic the rest of the world was – an island of mercy.

In a world that changes too fast to follow, it’s comforting to know Charlie Brown is still the same, Spider-Man is still the same, Mickey Mouse is still same. I am sure that there are enough people in France and Belgium and other European countries that reacted to the Disney duology in the same manner that I react to another announcement from Marvel on Civil War III or Grand Design or any other backward-looking project.

Silly Symphonies

In the case of the Disney Duology, this is a nostalgia that is not even my own. Disney comics, talking about comics featuring classic Disney characters rather than comics published through Disney’s subdivision named Marvel, are a very popular thing in many countries, but not where I grew up; I didn’t encounter them until I was well past my childhood. I read my Barks and Gottfredson – but it was with the eyes of an adult marveling at the craft (and cringing at the racism) rather than a child enjoying the adventures and hijinks. I like these comics, but I don’t love them in the manner Trondheim and Keramidas do, in the manner they expect the readers to love them.

Which is possibly why these albums work for me after all. Were I already overtly familiar with the comics adventure of Mickey and Co. I would probably recoil from another work trying to leverage my emotional connection with an older work. Even if the work was meant un-cynically, and no matter what the creators intended, this is still a Disney product ™, with all the expected corporate cynicism grafted on as a manner of course. Instead, I feel like I’m visiting someone else’s memory – which means it feels fresh to me. This is not something I grew tired of (yet).

It helps that the level of craft involved is very high indeed. Trondheim probably doesn’t need to be introduced to anyone reading a comics-criticism magazine. Suffice it to say he’s been one of the most famous names in the Franco-Belgian scene, as a writer and an artist, for more than three decades now. Nicolas Keramidas is the Disney connection, working for the company’s animation division since the late 1990s.

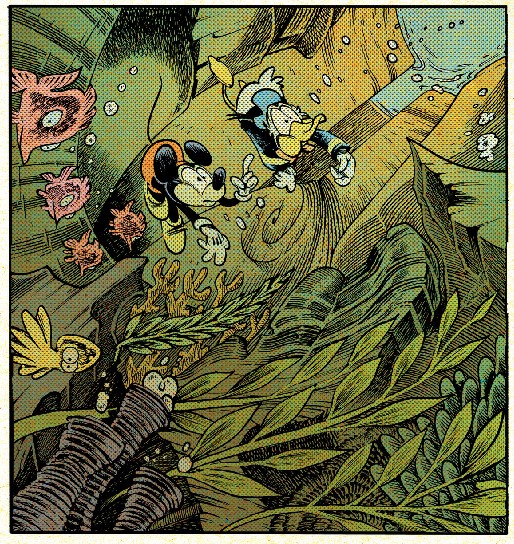

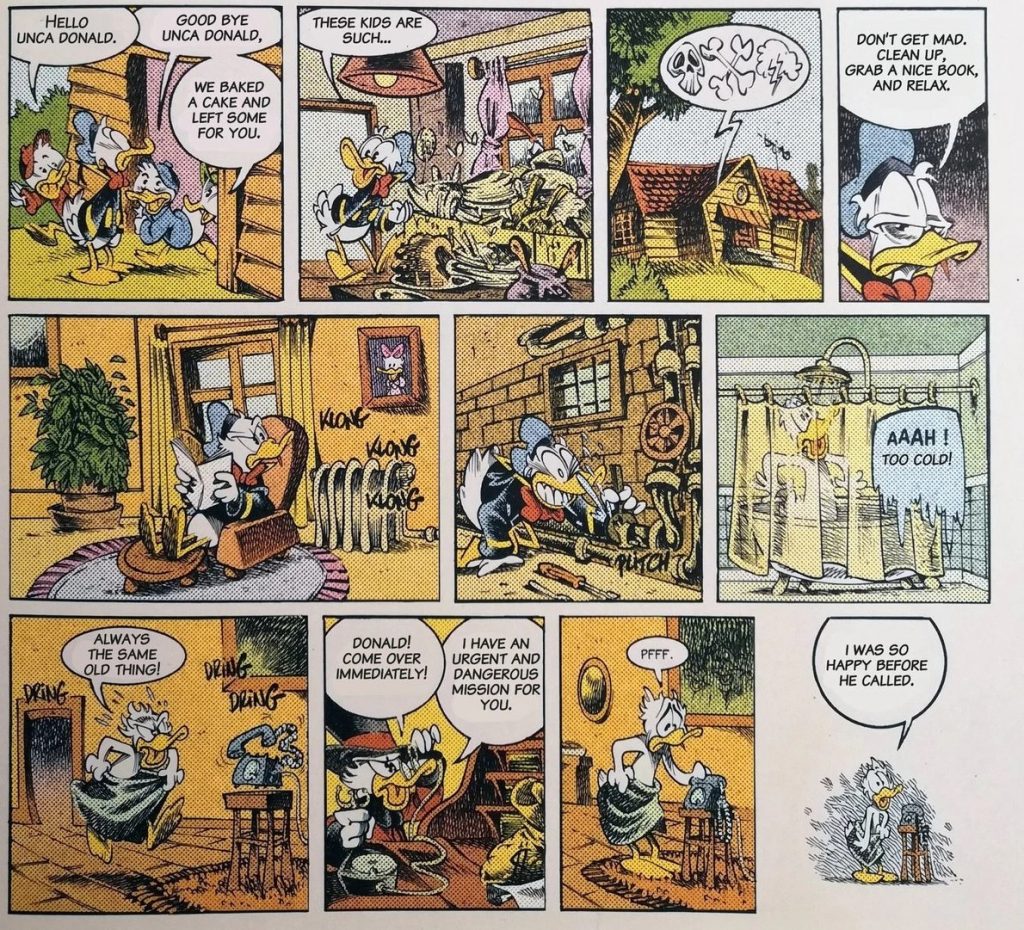

Indeed, Keramidas’ work here does not particularly remind me of classic Disney comics, the few of which I read, in terms of character design and dynamism. The expressions are a bit too wild. The movements are a bit too extreme in their swinging limbs. It’s “cartoonish,” in the sense that it reminds me more of (modern) television cartoons that intentionally evoke the past, rather than actual work of comics from a bygone era. Like that 2013 series of Mickey Mouse cartoon shorts – it is obviously of its own age but contains within it the yearning for what used to be.

In his very style, Keramidas seems to embody the impossible contradiction of Schrodinger’s Mickey Mouse: both modern and ancient; winking at adults with a knowing smile while sending an outstretched hand to the inner child. This is especially noticeable in the title panel of each page, which is often presented in a more abstract manner; if each solo page needs to embody the whole notion of a “Mickey Mouse adventure” by itself, then each title panel needs to further stand for the page as whole. Every fraction of every page needs not only to progress the story but also to be – to be immediately recognizable, immediately understandable, and immediately conceivable as a Mickey Mouse story.

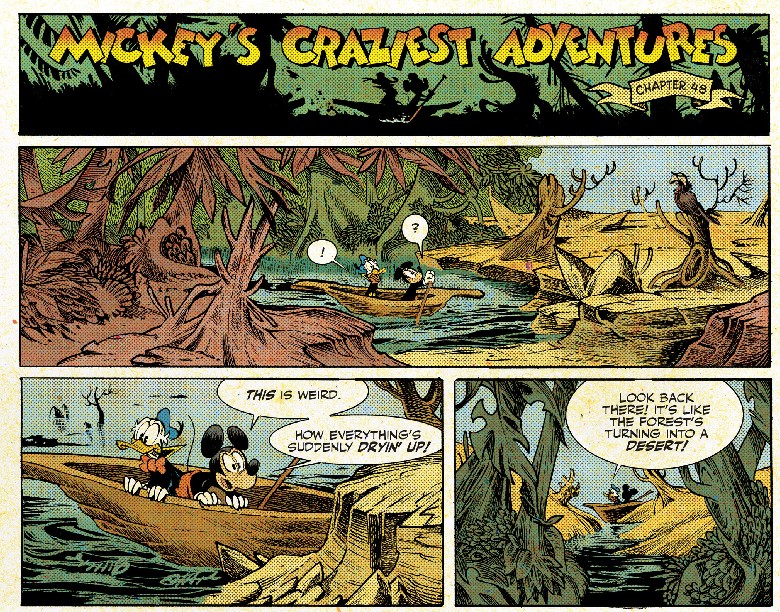

Yet, even under all that symbolic burden, Mickey’s Craziest Adventure is just fun to look at. Like the best of Tintin, there’s a balance between the sheer adventurism of the work, moving from place to place and experiencing new things, with a shameless approach to slapstick comedy. And just like Tintin, it carries a sense of something that was already classic when it came out, if etched into our memories. The page layout, the very structure of the story, feels closer to the mark of older comics. It’s nice to read a work in which every single page works as an independent storytelling unit, without sacrificing the sense of forward progression.

History Repeats

No matter the quality of the art though, I doubt anybody would be fooled into thinking of this as a true lost classic. Not that anyone is seriously expected to. We are all playacting here. This isn’t an elaborate prank, which ends with “we fooled you!” This is a continuation of childhood’s ritual, in which children take stories that were told to them and retell them in their own fashion: Haphazardly, without care for proper plot and character construction, and with a dash of our own inventions thrown in for good measure. Whether playacting with toys or trying to recall a story told by older relatives, everything gets reinterpreted in the child’s own lingo.

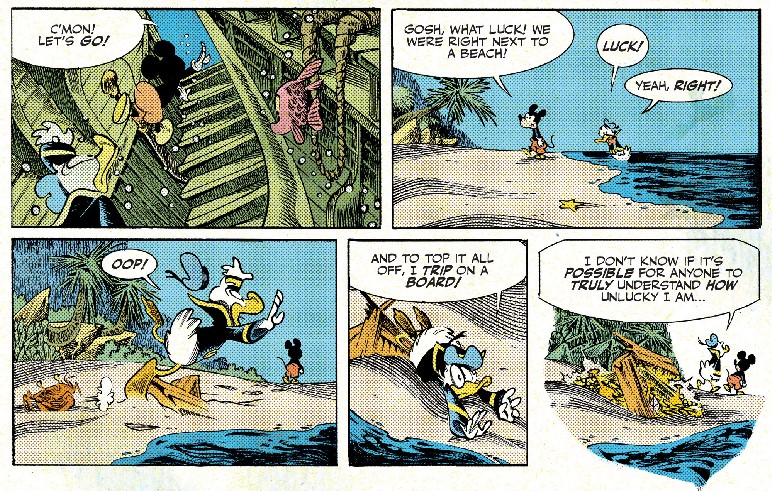

Mickey’s Craziest Adventure has everything that a child might want from a Mickey Mouse story – evil bad guys (yet not threatening enough to scare you away), mad scientists, lost civilizations, strange sceneries… and it contains nothing that might be bothersome. When our heroes are backed into an inescapable corner – they simply escape it via a jump to a new chapter, skipping over the wholly difficult subject of actually explaining the escape. Remember that bit in Misery with Annie complaining about “the cockadoodie car?” here Trondheim and Keramidas leap straight into that bit with utter shamelessness. Just as a child would, just as they expect us to do. To ask for “logic” is to defy the very nature of this particular story. It is, after all, the Craziest adventure.

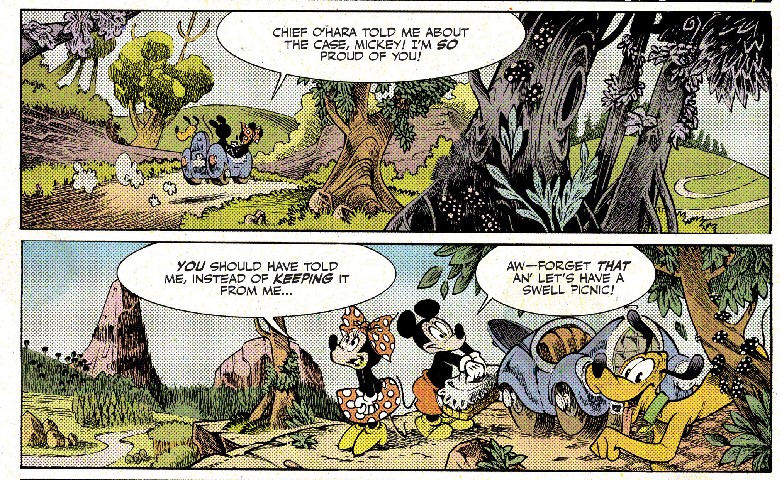

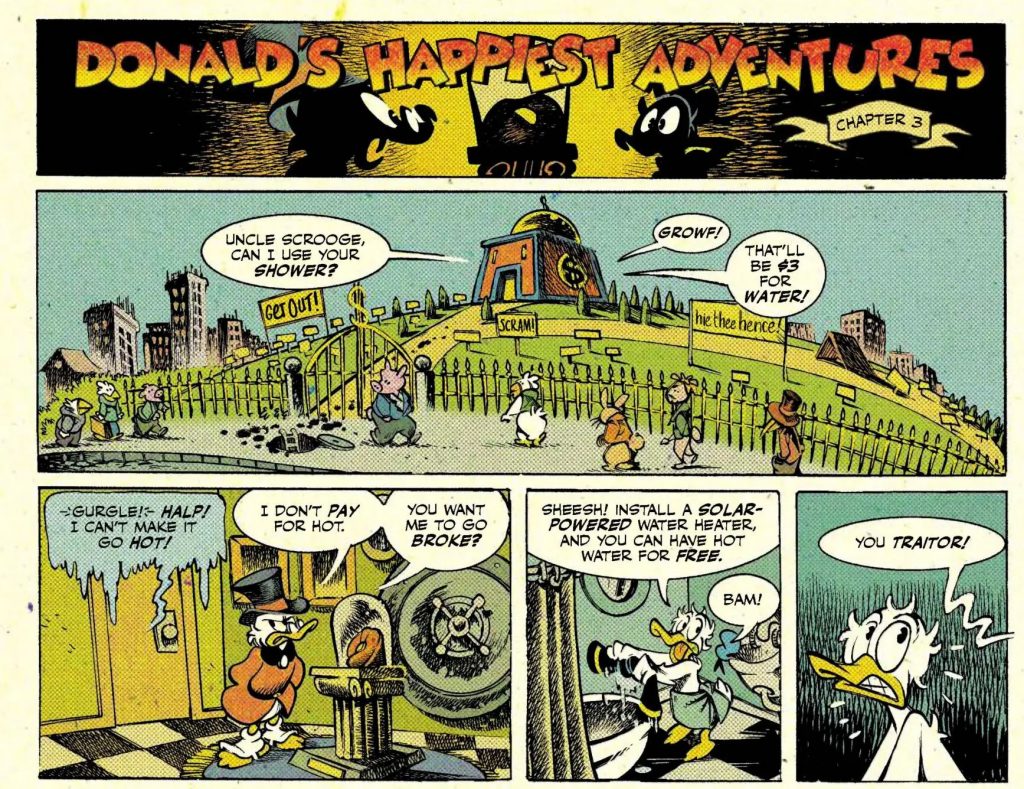

This is possibly why Mickey’s Craziest Adventure works better than Donald’s Happiest Adventure. Granted, playing the same trick twice would probably be just as tiring; but without it what you end up with is a rather familiar story, featuring all the usual suspects of Donald Duck comics (the nephews, Uncle Scrooge, Gladstone Gender, Brutopia), as if ticking-up boxes. What works with Mickey Mouse, a character long-ago voided of any actual “character” until only a hollow mascot remains, does not work so well with the better-defined Donald Duck. Especially considering how utterly Happiest Adventure is indebted to the Carl Barks canon.

Mickey Mouse can be wielded as a blunt instrument in favor of storytelling experiments because he serves as a symbol of childhood for so many. Even those that did not grow up with him recognize his visage (which is why he’s so easily used for mocking inversions of the Disney family brand). Donald does not work in the same manner; he is probably just as familiar, but as a grouse and grouch. There is something more inherently adult about Donald Duck: his constant responsibility for the three nephews, the job troubles, that extremely recognizable middle-class suburban life-style that Barks gave him, all of these mark him as a figure of identification for the older readers. While Mickey Mouse is as ageless as he is sexless.

Donald’s Happiest Adventure is, as the name might imply, about the search for happiness: Ordered by rich Uncle Scrooge to find the secret of true happiness, Donald is sent to and fro. He encounters all the obvious answers (money, good fortune, power, to help others) and rejects each in turn. There could be no proper answer because the only characters who appear truly happy in the story are nephews; their happiness is their ignorance / innocence, which no adult could duplicate. Which is where Disney comes in; for in Disney, since the company’s earliest days, comes the promise to return the adult to a state of child-like wonder.

What is expressed through the art and style in Craziest Adventure, the child-like zest, becomes the subject of the writing in Happiest Adventure. The subtext becomes text, revealing its manipulative nature. One cannot consciously decide to adopt the mind of a child, at least not successfully. While there are many adults today who hang on the charms of Disney, who swear fidelity to its products (its “content”) this always reads to me with an air of desperation. To intentionally reject the problems of the world in favor of brightly-colored cartoons (and their live-action remakes), is not to find the peacefulness of childhood, but the paranoia of an Ostrich with its head in the sand. Only a child can close their eyes and pretend the universe is gone; the adult knows better – no much how they pretend.

Like Donald in this graphic novel trying to find a simple answer to an impossible conundrum, the answer can never be found in Disney comics, only a temporary escape hatch. Nostalgia is a refuge from which one must eventually come back to reality. Ironically enough, this is the biggest lesson to be learned from the retro-fest of Trondheim and Keramidas. See? You can still find good lessons in Disney content!

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply