A Japanese navy captain arrives at one of Okinawa’s islands and asks to speak to the islanders. “We have come to Maeshima,” he says, “to defend this island. The state of the war grows more urgent with each passing day. A decisive battle is inevitable. This island and Okinawa will at last be a battleground.” Those two words, at last, ever so jagged in their intent: not only chronological but valorizing as well. The islanders look on the Japanese captain, stunned; most of them are old and tired, the younger denizens having been sent off to fight the war of a nation that has claimed them as its own, without particularly asking them beforehand.

It is this sequence that opens, and rather sets the tone for, Okinawa, a hefty collection of short stories by Susumu Higa (translated by Jocelyne Allen), initially released digitally via the online publishing arm of the podcast Mangasplaining and brought to print by Fantagraphics this past August. Comprised of two previous (and previously untranslated) collections by Higa, 1995’s Sword of Sand and 2010’s Mabui, Higa attempts a granular view of the American-Japanese conflicts over the eponymous grouping of islands and the islanders caught in their wake.

From “Sword of Sand.”

In his note at the end of the final story of the book, “Mabui,” Higa writes that around 1970, as control of Okinawa was being returned to Japan after decades of American military rule, “it was a period of significant social upheaval,” and that “politics were woven into the fabric of everyday life for the Okinawan people.” And this does reflect a core urge in many of Higa’s stories, as they present a panoramic view of Okinawan life possibly more comprehensive than most other manga before, certainly more than any work that’s crossed over to the English-reading sphere; there is a very present desire to articulate Okinawa as a place that is, in fact, alive and distinct beyond the theoretical realm of political power, darting across various walks of life to focus not on the higher-ups playing tug-of-war with the former sovereignty but on the conventionally ‘inconsequential’ people, who are affected more than they could affect.

The cost of this juxtaposition, however, is an excess focus on role rather than individual character. Several of the stories in Okinawa are inspired by newspaper articles about the island’s local color, with Higa projecting an interiority onto the factual basis, which only tends to underscore his limitations in writing; few of his characters manage to set themselves apart as fully human, often coming across as ready-made for their particular circumstances yet largely interchangeable on any larger scale. This is made clear in Mabui, wherein Higa returns to a character that first appears in the last story of the first collection, an Okinawan yuta or medium-priestess by the name of Mrs. Asato, using her to explore the role of religion and spirituality in Okinawa. Though Mrs. Asato appears in all but one of Mabui‘s stories (in the final one she is replaced by a different yuta), her role is less of a protagonist and more of a function of plot, a matter-of-fact prescriber and instigator of ritual, itself shown in scarce detail.

There is something to be said, in this context, about the surprisingly earthly nature of Higa’s approach to the spiritual, which here appears not as a realm discrete and distinct but as an extension of one’s heritage and territory, a living-on of the past; it exists as trauma to be resolved (in the case of “Dirt Thieves,” where a potter’s apprentice suffers from strange visions only to learn that the bones found in the earth used by the potter include the bones of the apprentice’s own grandfather), or else as the almost E.C. Comics-esque manifestation of a moral trespass to be recanted (in the case of “Mabui’s” ‘artist,’ robbing graves for a quick buck). Mentions of gods and greater divinity are made on occasion, but the focus is on a more immediate connection to self. Interestingly, the principle of Okinawan spirituality is not, as such, limited to Okinawan people. In “The Journey of Jim Thomas,” a middle-aged American ex-troop returns to his former station to meet the local baseball team he’d trained in his service; he is accompanied by his wife, who had initially dated his brother who was killed in action during the Pacific War. It is through Mrs. Asato’s ugan ritual that the now-long-married couple see the dead brother one last time—as he gives them his blessing.

From “Mabui.”

The stories within each of the two collections are not laid out chronologically—Higa’s first-ever comic, “School,” is presented as the sixth story in Sword of Sand—yet Higa’s cartooning shows no substantial fluctuation in quality, no real progress; from the first moment his art appears to be fully formed to an almost frustrating degree, disabusing the reader of any notion of linear progress. While not bad by any stretch, Higa’s cartooning somewhat complements his struggles with writing, as he inserts himself into a post-gekiga lineage while shaving off any jagged edges. His character work, though clear in its action, is clean and stiff almost to the point of a perfunctory blankness; the relations between character and backdrop are flattened, and characters are textured in a largely uniform and unvarying line weight interrupted only by hatched shading. Higa fares a bit better with landscapes and terrain through a richer textural articulation, though the contrast between character and surrounding is not stark enough to seem as intentional as often opted by the first generations of gekiga creators, instead coming across as a mere default.

“Call of Sand,” depicting the arrival of the American military for the Battle of Okinawa, delineates the contrast between the Japanese and American armies; the last vestiges of the Japanese army encourage Okinawan civilians to kill themselves in order to die in honor, whereas the Americans treat them, to the extent enabled by circumstance, more respectfully than expected. “Why would you be so nice to us, an enemy people?” one Okinawan asks. “Our army is the army,” an American soldier replies. “It’s not frightened civilians. It’s very hard for us to see children and the elderly get caught in our attacks and die. The hearts of American soldiers are also hurt. We are not savages.”

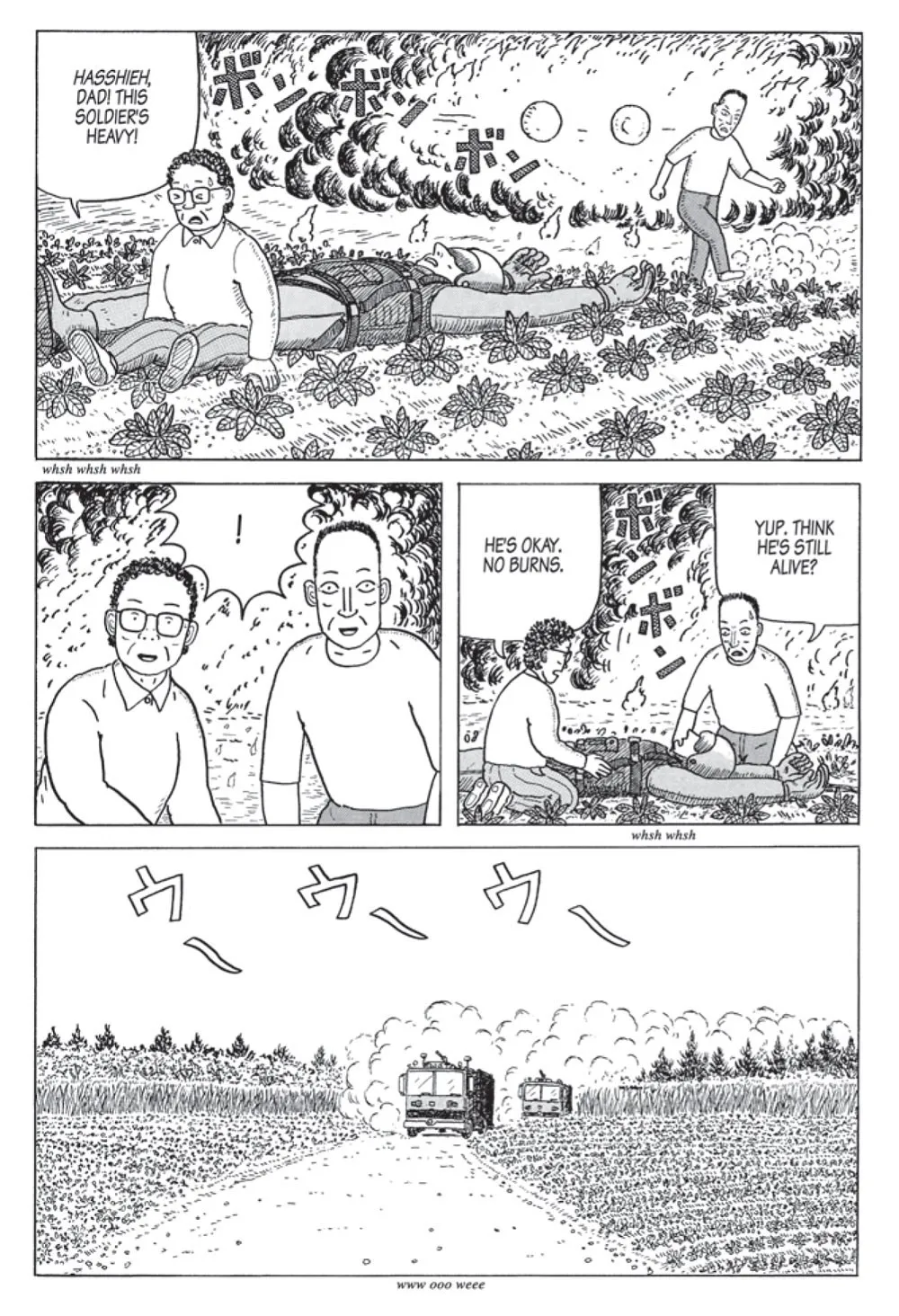

This divide, between system and representative thereof, serves as a key to Higa’s stories; the system becomes something of a disembodied abstract force, running regardless of the particular individuals enforcing it on the minute day-to-day basis. And there is, in fact, a mutual appreciation there, on an individual basis, an appreciation which Higa frames as transcending the military dynamic: the baseball coach Jim Thomas is admired by his local team; the farmer couple in “Tolerated Cultivation” who save the life of a crash-landing American soldier, view him with kindness and friendship, in spite of the fact that his base is located on their land, constraining their farming and affecting their quality of life. This form of empathy, or at least sympathy, is itself a form of pragma, in that it allows for a relatively frictionless, even amicable dynamic.

From “Tolerated Cultivation.”

But Higa is nonetheless conscious of the limits of this divide. Even with kind individuals, the system still upholds its constraints, still greatly limiting the cultural autonomy of the islanders. It is at these moments of friction and conflict—internal, external—that Higa is at his best. At the end of “Call of Sand,” one of the American soldiers stands alongside the Okinawan man hired as a liaison between the army and the local community, and they look on the construction of the American army base; the latter man the Americans have nicknamed Tony, because they could not manage to commit the pronunciation of his actual name, Komesu, to memory. “This used to be a huge village…” ‘Tony’ laments. “So America’s going to occupy Okinawa now? You and Pete are good people. But why… so many people died, were hurt… and now this. It’s so sad, Roger…” But Roger does not know what to say, and indeed the story ends there; no answer would ever come.

Higa himself is not particularly optimistic regarding the political state of Okinawa. In an interview conducted by Mangasplaining publishers Christopher and Andrew Woodrow-Butcher, included as supplementary material at the end of the print edition, he says, “I did have dreams of something better, but we’re pretty aware of the fact of colonization here[… O]ne thing that’s certain is that our understanding of the situation has gotten harder, more bitter.” What, then, remains? In his stories, it is an internal tenacity of identity, regardless of and in spite of oppression, that reigns; external encroachments may constrain but never eliminate. Any attempt at subsumption can never reach the absolute; subjugation may take very real tolls, but the notion of a cultural overwrite is a fallacy. Losing himself, as he might, between abstract collective and tangible individual, one thing is certain: to Susumu Higa, Okinawa is nonetheless alive.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply