“In the space between,” a disaffected factory worker of Eden II proclaims during a psychedelic experience before the hundredth page of the 452-page Fantagraphics tome, “a world manifests in reverse.” Like an enchanted mirror, K. Wroten’s Eden II constructs a wondrous facsimile of depth, strangely flat and cool to the touch by virtue of its design. The mental-health-adjacent spiritual development prescribed in the book’s hurried conclusion is not enough to steer Wroten clear of the mistakes they outlined in their earlier graphic novel; Cannonball’s protagonist Caroline Bertram is a perceptive portrait of a young artist’s worst impulses. As she blows through relationships in her pursuit of recognition for her dormant genius, success for a young adult novel (a pursuit far below her) turns out to be more unbearable than languishing unknown. Eden II accelerates Bertram’s values and paranoias to their most extreme conclusions and pronounces that the results are, somehow, radically different. Trapped between a past the reader is ridiculed for trying to understand and a future that repulses the author except by literal rapture, there is not a lot of room for actual reflection. Once you feel the glass, this book that styles itself as an anticapitalist critique and philosophical deep-dive mirrors its seismic ambition by working overtime against itself.

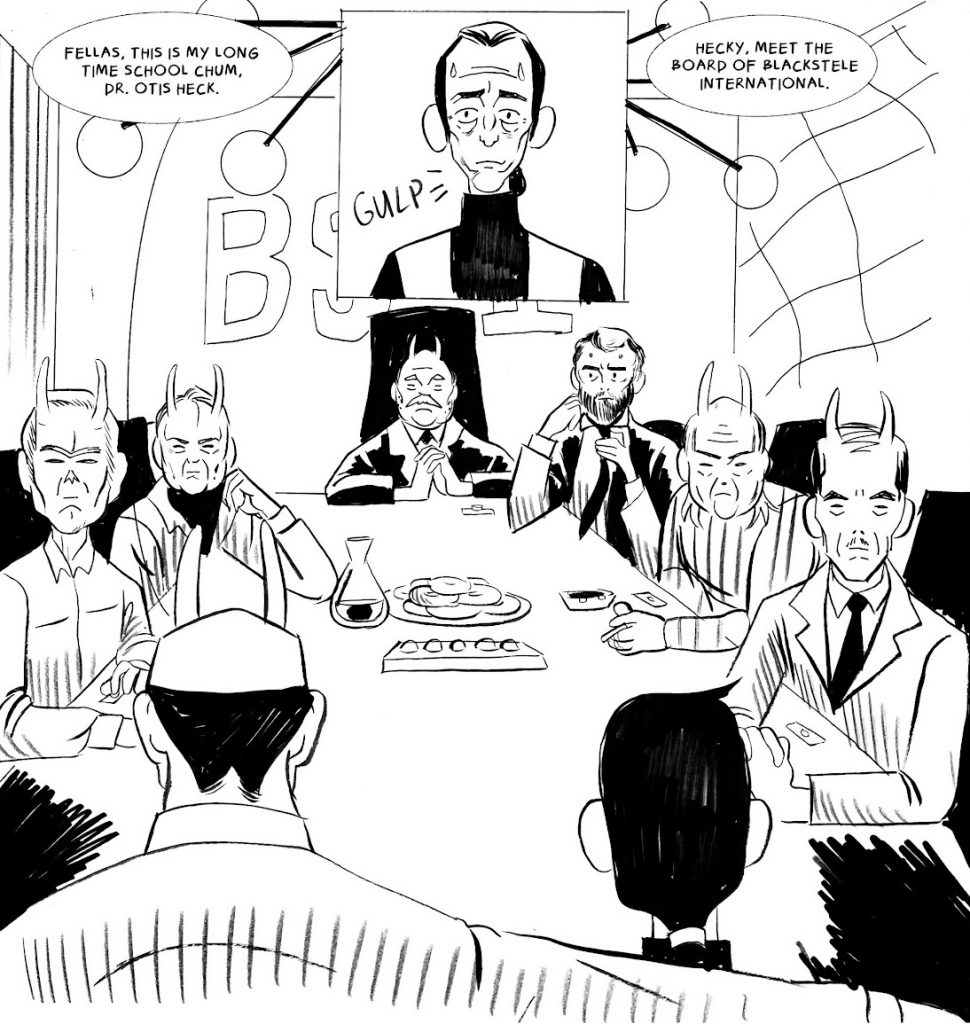

Eden II takes place on a shielded Earth that has been drained of all its natural resources. Anxious protégé Ellis Flowers and their haggard mentor Otis Heck have just created the world’s greatest beyond-virtual reality: Eden. Through what Wroten calls “the Monad,” mind/body duality is solved for good. This success is threatened by a cabal of horned businessmen (resembling figures from a race conspiracy the book does not subvert) who, like the Magus in Cannonball, aim to corrupt the extra reality – if it isn’t damned already – with their all-consuming power. Ellis and their friends must survive a last-minute confrontation with their shadows to rise to the occasion of the final showdown. Heck’s gifted young daughter, Hap, sacrifices herself to become a part of Eden’s server, and all of the capitalists are slaughtered before Ellis & company are uploaded permanently into a new Eden. This market-free heaven is guarded earthside by an exterminating angel and her chicken companion.

What is Eden II trying to say, and does it mean it? Depiction is not tantamount to endorsement; a reader can certainly come to their own conclusions, but Wroten frequently walks a line between parodying and proselytizing where it is not altogether clear whether something is deliberately ambiguous or if an idea simply has not been developed. The project of Eden II, as I understand it, is to use Wroten’s catalog of personal mythology to transcend previous dialogues on philosophy and art, emerging into a brave new world where bodies and symbols are merged; this work is a winding, sometimes-meandering declaration of the author moving on from just about everything but their work. By this metric, Eden II is successful, albeit to the detriment of its beating heart and political salience. In its well-intentioned (and literally heroic) quest to create a wholly original world where artmaking and spiritual development will flourish, this book fails to realize it is cannibalizing its own tail. Hyper-individualist values undermine the reach Eden II eventually makes towards connection, having so heavily informed both its political attitude (the literal masturbatory dangers of the welfare state, the necessity of solely owning one’s image) and effectively glorified its non-reliance on other sources. By accidentally rejecting interdependence as some manner of spiritual corruption – thereby straining its own gestures at romantic love and familial loyalty – Eden II is also barred from openly engaging with most of the thinkers it generously name drops, spurning ideas that might have informed or challenged its speculative approach to spiritualism or its dubious interpretation of relations of production. The Ouroboros is fated to eat itself alive, mistaking new ideas for hateful reflections and old conservative ideas for urgent new ones.

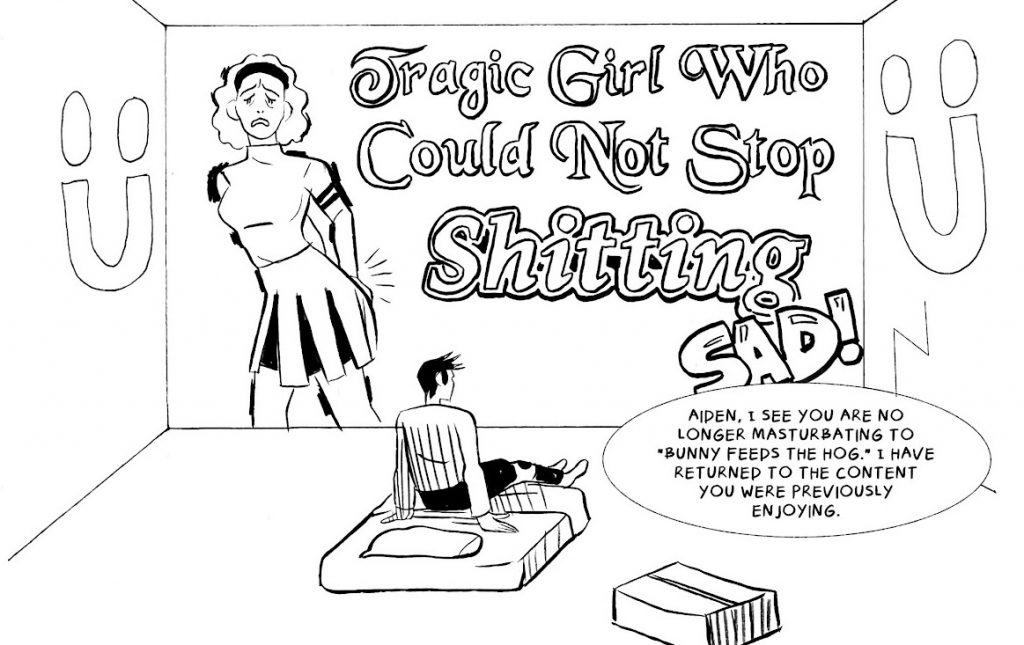

To Wroten’s credit, Eden II is an undeniable stylistic and professional achievement: the work is beautiful and often outrageously funny. In a bedroom plastered with artificial pornographic advertisements, one delightfully upsetting segment boasts, “tragic girl who could not stop shitting / SAD!” The actress is bent in misery, with Wroten’s flexible and enviably confident cartooning conveying every line of her pitiable position with perfect precision. This is a book that relishes a very specific use of language, planting wickedly appealing phrases in a reader’s head such as “crapping thine pants” and “pugnacious worm.” At its best, Eden II is both endearingly dreadful and slap-happy with its own silliness, evoking a sparser and more beautified Jhonen Vasquez. Wroten also has an enduring appreciation for muscular women and excels at drawing them. These characters were so important to the fabric of Cannonball that the graphic novel is named after a female wrestler who only makes sparing appearances in the story. One such muscle-mommy in Eden II, Bunny (mother to Hap Heck, estranged wife of Otis Heck), is depicted with so much love that her every appearance feels profoundly important.

Reading Eden II, it is abundantly clear that Wroten’s particular genius might flourish with something as straightforward as more editorial support or a collaborator. When their curiosity – uncluttered by Bertram’s doomed mission to prove something – gets an opportunity to take up space on the page, it sparkles with an energy one might go so far as to call brilliant. For this reason, the strongest and most distinctive character in the book is easily Hap Heck, a wunderkind whose true intelligence lies in her ability to parse what is simple. Before her school essay is undercut by a punchline that exemplifies Wroten’s ongoing oscillation between showing off dazzling fragments of academese and betraying a bristling hostility to the very vocabulary that lends their work its sheen of prestige, Hap concludes quite clearly, “What use is living without love?”

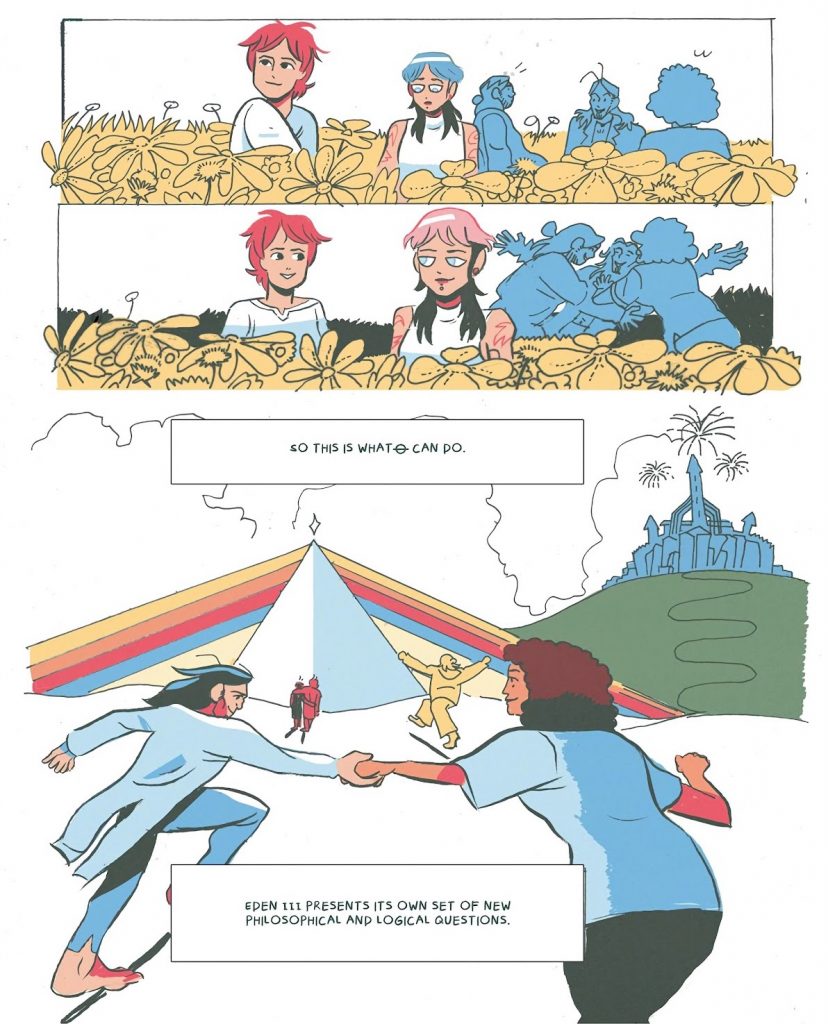

What had worked so spectacularly well about Lambda Literary Award winner Cannonball was Wroten’s commitment to follow through on the story’s logic. That graphic novel constructed a bleak vision of the world through the eyes of its protagonist, where glimmers of artistic inspiration are the only thing worth living for. These endeavors never pay off the way the world promises they will: Cannonball’s Caroline Bertram ends the story drunk, passed out under a table at an awards show where the book she alienated everyone in her life to pursue is being honored. “What can she dream about?” someone asks on the final page of Cannonball. “She already has everything.” In Eden II, Wroten’s characters fall into the same annihilation fantasies and bootstrap traps, albeit with more positive narrative framing and the addition of global political and spiritual dimensions. “So this is what ø can do,” Ellis narrates in Eden II’s finale as his friends wake up in a utopia where everybody is wearing white. Here, ø (the “monadic equation”) symbolizes a re-interpretation of Caroline’s empty everything. What the expansion of scope in Eden II does, despite the “happy ending” (and its tongue-in-cheek epilogue, which is truer to form), is strengthen the bourgeois assumptions about the world made in Cannonball rather than challenge them. It is as if, after demonstrating quite effectively how a certain “productive” orientation to the world is dysfunctional, Wroten tries to escape its stifling hold through the very thing it prescribes: sheer generation of pages. In Eden II, creative achievement is still tantamount to perfection, heightened to cosmological levels with its full-hearted but ultimately superficial engagements with mysticism and art discourses.

Here, art is philosophy is psychology is spirituality is politics; Wroten’s shallow interpretation of the Demiurge mistakes a simplistic flattening (misrepresenting both monistic thought and any ideology left of Reaganism) for egalitarianism, a revelation helpful only for a tenuous foothold into “wellness” and accelerated human production of art objects. At best, references to scholarly works are used with as much depth as the quotation blocks alongside pages of The Artist’s Way, affirming the economically transcendent miracles of just creating. At worst, they bolster a paranoid cynicism, used as fodder to prove that everybody is out to vampirize the good juice from our heroes. Reacting to Hap’s moving essay likening her father to the Tin Man from The Wizard of Oz, a classmate scoffs, “My pre-K report focused on the theories of Henry Littlefield. You haven’t even mentioned the book as an allegory for early 20th century monetary policy!” This is a throwaway joke to emphasize how isolated Hap is, but assumes the reader must agree that love itself is incompatible with history.

This is a reactionary stance, and a powerful indication of how little regard Wroten has for their own settings and symbols: the realized nightmares of capitalism are used as location backdrops in Eden II (a “primitive shapes” factory where the workers have numbers but no names; a not-so-authentic New Jersey castle formerly overrun with endangered wolves; a bedroom walled with unskippable advertisements), but it is somehow pitiable to Wroten – and even cruel – to draw a line between the Tin Man and political scholarship. For all of Eden II’s criticism of the psychic effects of capitalism, this attitude makes it bizarrely unfriendly to even the most sincere pursuit of the re-appropriation of the means of production by workers. Materialism and its militant application have no place in Eden II; Marxism may as well be as useless as the economic system it rigorously vivisects, if spiritual vagaries are our best bandage for the apocalypse.

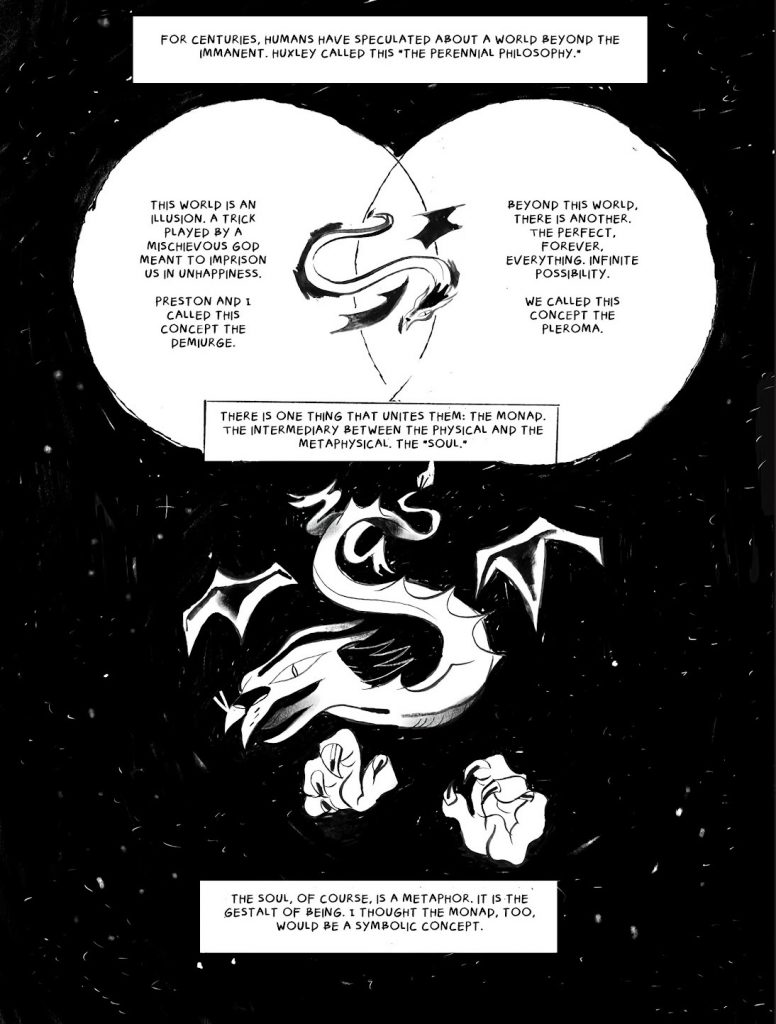

Most consequentially, the “Monad,” as invoked in Eden II, bears no resemblance to any historical conceptions of the term I am familiar with. Ellis Flowers opens their first section by telling the reader that they once believed it was only conceptual – until, that is, they found it. This is the ultimate technological fix to the mind/body split, employed by magic with a bit of Star Trek positivism (the compatibility node that compatibilizes with its compatibilizers). This would not be worth mentioning if Eden II were an entertaining science fiction romp, but this book goes to great lengths to shake that possibility; what we are confronted with is an evasively sardonic New Age manifesto, where philosophical terms are primarily utilized in service of psychologized riffs on what Wroten proposes they could mean, if everyone bettered themselves correctly. For simplicity’s sake, the title “monad” might be understood as an artistic flourish here, much like the iconic biblical names in Evangelion. This is fun for improvising associations, as Wroten’s creative quickness shows off, but makes weak grounds for remedying any of the text’s existential yearnings.

The “monad” fix to the mind/body split is only necessary when we fail to ask: why do we believe the physical and the psychic are at odds with one another at all? This is not a transcendental truth (or, as Wroten seems to speculate at the last minute, an emotional wound) but a historical position, stemming from our own activity. The injury Wroten identifies in earnest is born of material conditions – owners purchase the labor power of workers as a commodity, producing alienation in both classes – and cannot be remedied by “overcoming” a philosophical aporia on a purely ideological plane (or by the feel-good slaughter of capitalists on its own and in pursuit of changing what amounts to bourgeois managerial roles). Eden II treats the spectacle the schism produces as its origin, more comfortable falling back on conservative narratives of technologically-mediated social decline and backroom conspiracies than fully approaching any of the hundred fascinating little ruptures in the psyche that it identifies. In lieu of fully considering any one of them, Eden II invents elaborate and confusing plot devices to justify its allegedly total enlightenment; hence, the “monad”.

Committed readers must go along for the ride, but Eden II does not make this easy; Wroten’s philosophical imprecision has the effect of both turning away readers who are unfamiliar with the jargon they use and generating a dead end for those who would like to understand the way they mean to use it. The flip side of this woolly approach to philosophy is its neoliberal underbelly, where unimaginative interpretations of very real crises get taken for granted. This is how a book that is fundamentally about love can be so readily set on a post-total-extraction earth. How does a class of elites continue to run the world from inside the United States if there is no resource-rich Global South to steal from? How might this total disinterest in imperialism be a convenient feature of the techno-utopian fantasy, and not just an unfortunate detail?

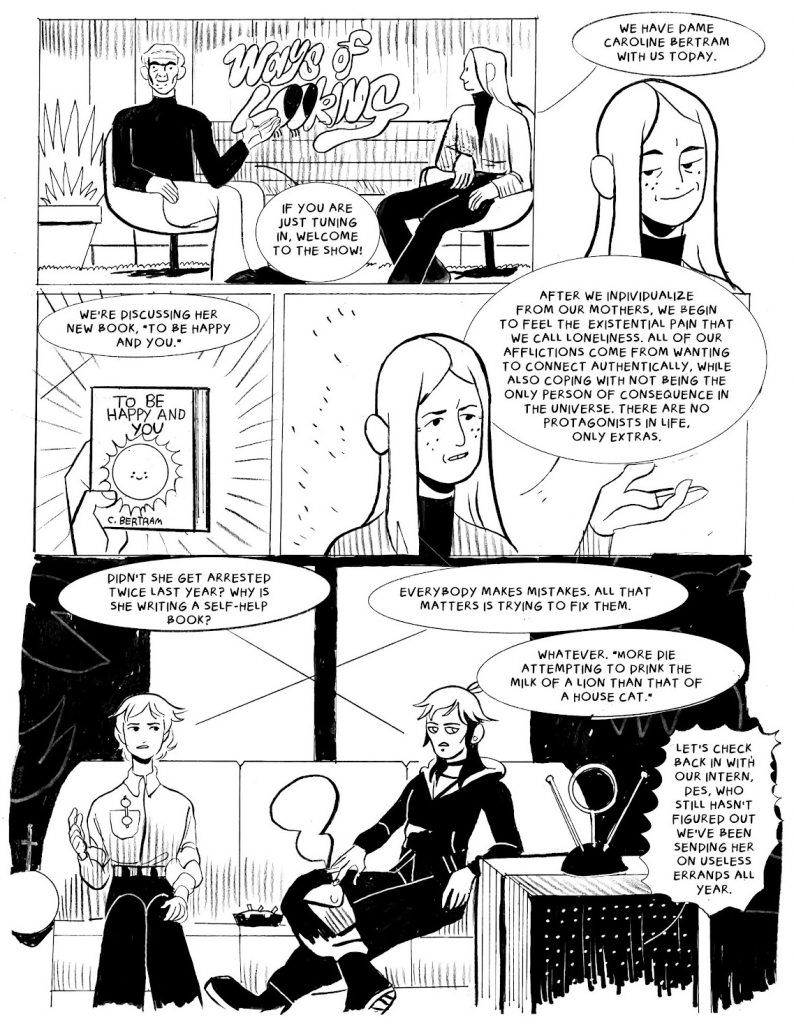

In Cannonball, Caroline Bertram mistook questions from a radio interviewer for personal attacks to be met with in turn. Between condescending accusations, she ranted about the all-consuming forces of hatred that have controlled her life, and how she strived to slay them in her work: “He was the evil wind that blew through my childhood, my safety, my peace and tore down any objects of cathexis leaving me in a wasteland devoid of refreshing psychic energy! [. . .] I thought defeating him would save me. But this wasn’t true. What I destroyed was a mere reflection of his power.”

Telling, here, is Bertram’s cameo in Eden II. She is a self-help author in this universe, notorious for her disorderly behavior but eventually commended by Spider (factory worker, roommate, and eventual lover of Ellis) for her ambition. “More die attempting to drink the milk of the lion than that of the housecat,” Spider says. This adage by Wroten suggests that Bertram’s valorous attempts to better herself are what land her in trouble, as if her personality was the driving force of all of the alienation in her life. By mistaking the ramifications of material circumstances – what Bertram called “Jesus and my dad and Mickey Mouse” in Cannonball – for a nebulous spiritual entity only surmountable by doubling down on an increasingly deadly commitment to become better, more optimized, more therapized and therefore good, Eden II ignores all available exits and sprints in circles. Rather than connecting personal stories to the wider world (as Daniel Clowes does in his masterclass Monica, or Blue Deliquanti in their devastating mini Adversary), this work’s ever-exacerbated ambitions generally involve pulling the world toward itself, and misunderstanding the world’s resistance to that arrangement as a denial of love in essence.

Rather than reconsider the utility of genius in the first place, Wroten remakes the world. They assert in both Cannonball and Eden II that capitalism has deceived their characters, not by constructing the savior-savant in the first place, but by sullying the allegedly virtuous and cosmically consequential potential of artmaking.

Ellis Flowers asks in earnest, like a child rationalizing the abuse they receive for being too smart, “Did I make something evil?” Eden II redeems Flowers’ invention (almost evil, then truly good) by feasting on its own body. Wroten gears up for a revolution but ultimately reverts, at the expense of their dreams for a liveable future – and despite the switch to color in their Eden-side sequences à la The Wizard of Oz – to black-and-white taxonomizing.

What depth do we lose by codifying anything – works of art, technology, graphic novels, and online reviews – as ontologically good or evil? Why do we keep telling the same story? What truths are we protecting ourselves from, and whose pockets are getting lined?

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply