What is Latinidad? A problematic term, as The Nation’s research director Miguel Salazar explored across several interviews with Latinx journalists, activists, and academics. In short, there is no such thing as “Latinx-ness” simply on the basis that identity is not an absolute, wherein association with a particular identity or culture comes at the expense of another. Latinx identities encompass a vast range of histories and contemporary experiences, including oftentimes marginalized black and indigenous perspectives. To say one voice or experience is more valid, “more Latinx,” than another would not only be blatant colonialism, but it also succumbs to the “danger of a single story” as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie famously described in her 2009 TED Talk.

A single story, fortunately, is not what readers get in Tales from La Vida: A Latinx Comics Anthology. Edited by Dr. Frederick Luis Aldama, Distinguished Professor at The Ohio State University, Tales from La Vida offers a panorama of Latinx narratives, featuring seventy unique vignettes and over eighty contributors. With eye-catching artwork, some pieces harken to fotonovelas (Leighanna Hidalgo, Fernando Balderas Rodriguez) while others, like Zeke Peña’s fleshy heart pulsing with nopales, are stand-alone striking. In total, the artwork in this anthology reflects a diverse range of histories and narratives, from personal accounts that address meaty subjects of identity, family, and belonging, to new takes on traditional folklore and snapshots of fancy.

In the creation of Tales from La Vida, contributors responded to the prompt, “What is the most significant moment in your life as a Latinx person?” Organized into sections that range from language and feeling between worlds to folklore and pop culture, this anthology contains stories that are deeply personal. Not one of these pieces is written fretting over the white gaze and questioning what would be appealing or sensational. In many cases, they are “small” stories, dissecting one-off encounters and moments of reflection for the author. It’s in these contained, personal vignettes that we see similarities to other Latinx experiences within the anthology itself.

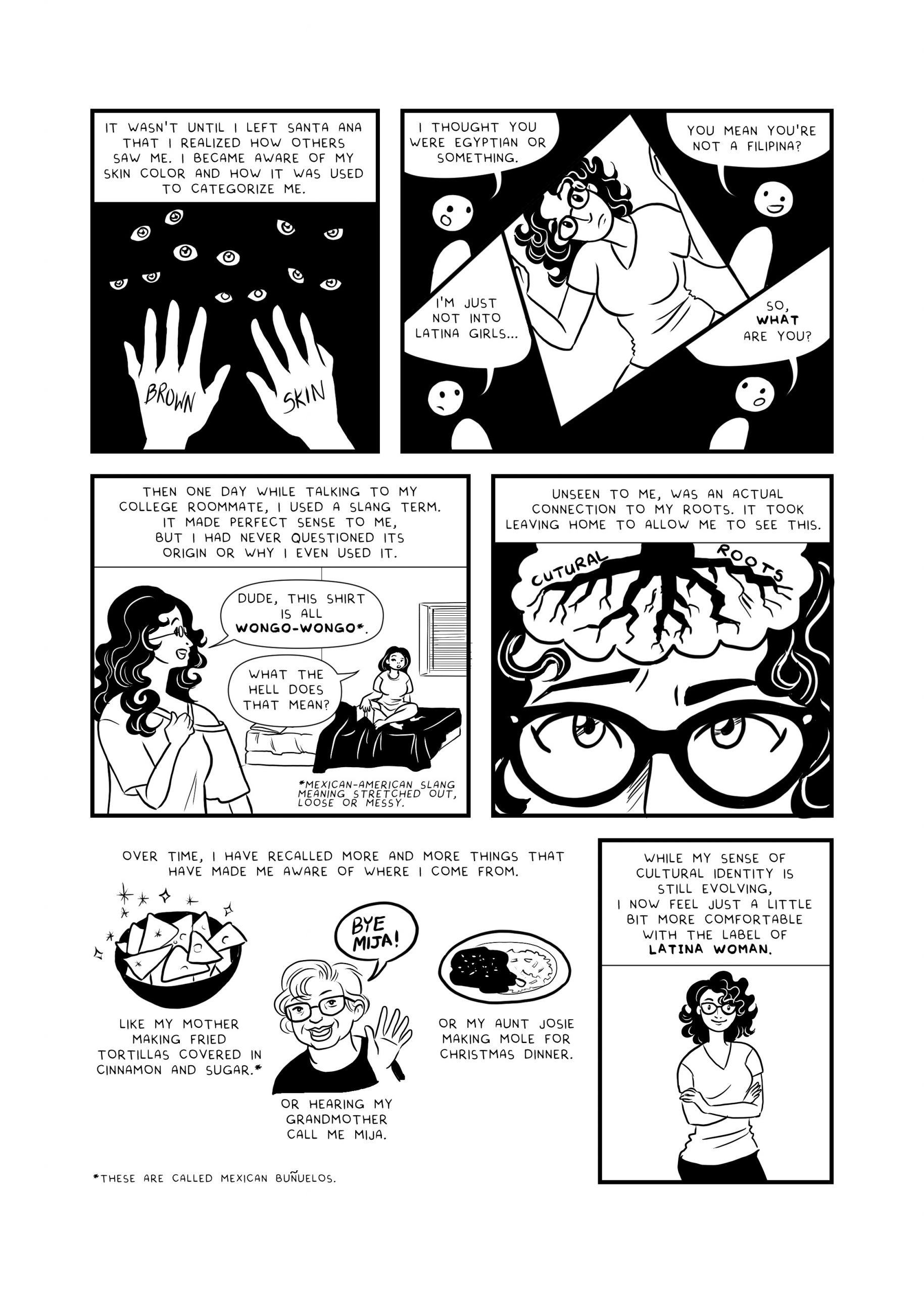

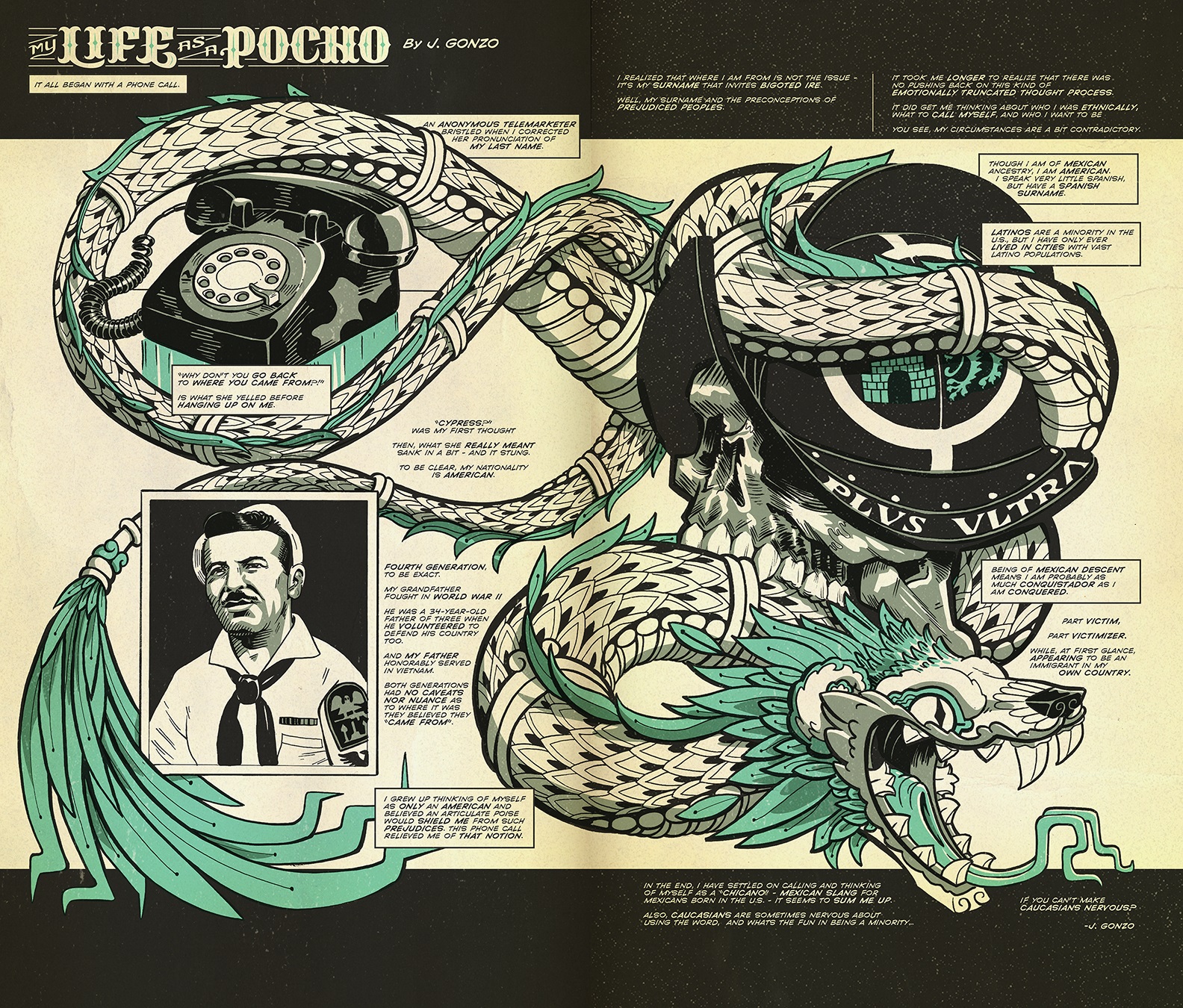

In “Wongo-Wongo,” Amber Padilla describes her life as a fifth-generation Mexican-American, how not being fluent in Spanish and having a family that revered its service in the US military made her feel disconnected from identifying as Latina. We see parallels of Padilla’s story in Crystal Gonzalez’s “Latina in the Middle,” who doesn’t speak Spanish, and in Jason “J-Gonzo” González’s “My Life as a Pocho,” whose family history also lauds service in the armed forces and identifies strongly with their American nationality.

For the uninitiated, “pocho” is a generally pejorative term used to describe “Americanized” Mexican-Americans. However, the trappings of being pocho/a/x are not exclusive to Mexican-Americans. In “No Time for Titles,” Adam Hernandez confesses to his professor that he feels like “a ‘bad’ Puerto Rican” for struggling to speak basic Spanish. Upon hearing this, his professor replies, “You shouldn’t feel ashamed. You ARE Latino!…This is your story.”

It’s moments like these that make my little pocha heart cry. Identity is not limited to one quintessential quality or by someone else’s yardstick of what meets a standard. Tales from La Vida proves this concept with a collective of seventy voices. It’s an orchestrated takedown of the “No True Scotsman” fallacy. Padilla highlights all the ways in which her family’s culture is very much alive and influential in her everyday identity, from her grandmother’s term of endearment (“mi’ja”) to her mother’s buñuelos. Hernandez reflects on a family trip to Puerto Rico and avows to encourage his “hermanos y hermanas” to be proud of their origins. And J-Gonzo visually sums up his identity in a beautiful two-page spread: a serpentine Quetzalcoatl wraps around a rotary phone (marking the impetus for his featured segment), a Spaniard’s helmet, and an illustrated photo of his grandfather in Navy uniform.

Of course, Tales from La Vida isn’t all pochx stories either. In “El Border Crossing,” Jaime Cortez captures the uneasy tension of belonging that wracks his family as they cross back into the States after a family trip to Mexico. Despite his parents being naturalized citizens and he and his siblings being American-born, they feel “less like citizens and more like tentative guests who could be summarily dis-invited.” Alberto Ledesma spotlights in “My Most Significant Moment as a Latino,” the instance when he embraced his undocumented identity and taught it as an American experience.

Also included in this anthology are narratives that explore Afro-Latinx identities (Carlos “Loso” Pérez) as well as the internalized anti-blackness that rises in spite of this (Breena Nuñez Peralta). There are also stories of being indigenous (Daniel Parada, John Jota Leaños), and mixed race (J.M. Hunter, Samuel Teer). Leighanna Hidalgo explores body types and career expectations, and José Cabrera’s “El Cabron” touches on domestic violence as he resolves to forgive his abusive father without re-engaging him. Tales from La Vida also exposes cultural hegemony and internalized oppression within our own Latinx community. Juan Argil’s “Güero” is haunting. Illustrated as if Argil had detonated a box of crayons, the vignette explodes with color — potentially ironic considering that “güero” refers to a fair-skinned Latinx person, someone with a leg up in a society built upon white supremacy.

While many of these subjects carry substantial weight, it should also be noted that this anthology is not fixated on trauma and oppression. After all, life has joy in it too! Appropriately, La Vida offers a number of humorous tales. For example, Dave Ortega’s “Your Name is the Rio Grande” got a belly-laugh out of me with its title punchline that fans of Spirited Away will instantly recognize. Likewise, Eric Esquivel and Michael Macropoulos introduce the reader to chupacabras that adopt a “vegetarian” diet to hilarious results — all within the space of four pages.

Perhaps that is what makes this anthology a feat of “identity Jenga”. Most stories are kept to a compact two- to four-pages. Unfortunately, this isn’t always enough room for the artists to create complete fictional arcs. Because of this constraint, some of the pieces do feel abbreviated, leaving a desire for more context. For instance, Kelly Fernandez gives the reader a glimpse into Dominican folklore with “The Ciguapa” when a young woman discovers that she and the legendary monster may be as intrigued as they are frightened of one another. Unfortunately, it ends there, leaving the reader asking, “And then what?”

So where to go from here? Tales from la Vida has a few thoughts on that, dedicating its final section to representation in pop culture. Visual representation — from comics to animation — plays a key role in both how we see ourselves and how others view us. Some of the artists in the anthology have contributed to the pantheon of comic book heroes by forging their own; Miky Ruiz invents El Vejigante-Luchador and Richard Dominguez brings forth El Gato Negro, to name only a couple.

Recently, there has been a groundswell of animation and comics featuring Latinx narratives: Disney’s Coco broke box office records in 2017, Miles Morales swung across the silver screen in 2018, The Casagrandes debuted in 2019, and this summer will welcome Onyx Equinox on Crunchyroll with Maya and the Three to follow on Netflix in 2021. On the indie comics front, Latinx graphic novels and comics series have achieved significant acclaim: Diary of a Reluctant Dreamer (Alberto Ledesma) was named a 2017 INDIES Finalist and Codex Black (Camilo Moncada) placed second in Comic Attack’s Top 5 Web Comics of 2019. Each of the aforementioned stories are nuanced in both characters and worlds, scattered across points in history and geographies. As Latinx stories gain mainstream traction, we’re able to see the multiplicity of perspectives that Tales from La Vida captures in a critical snapshot.

Perhaps most heartening is that these diverse perspectives within a given community may become the norm in storytelling. More and more, the “one story” won’t do. Most notably, 2020’s American Dirt debacle drew a justified firestorm of Latinx criticism for cutting a seven-figure book deal to a manuscript that amounted to little more than a sensationalist exploit over brown trauma. In holding Flatiron Books, an imprint of Macmillan, accountable, Latinx authors, academics, journalists, and community members spoke out against the massive promotional budget poured into one book — riddled with stereotypes no less — and they way it was plugged as a modern-day Grapes of Wrath. The ensuing #DignidadLiteraria (Literary Dignity) movement calls for uplifting the numerous and varied narratives of Latinx writers. Is this a new wave of storytelling? Not in the least. It’s the long-overdue recognition of these stories, and the authors who have been telling them for ages. Too many to choose from? Excelente — you don’t have to settle for one.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply