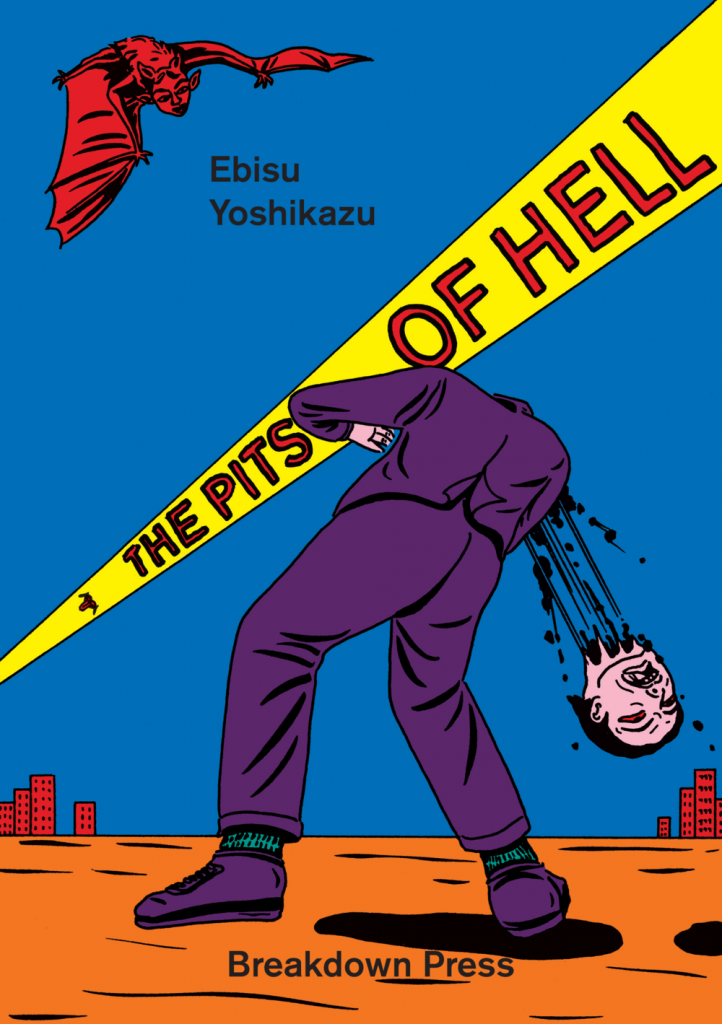

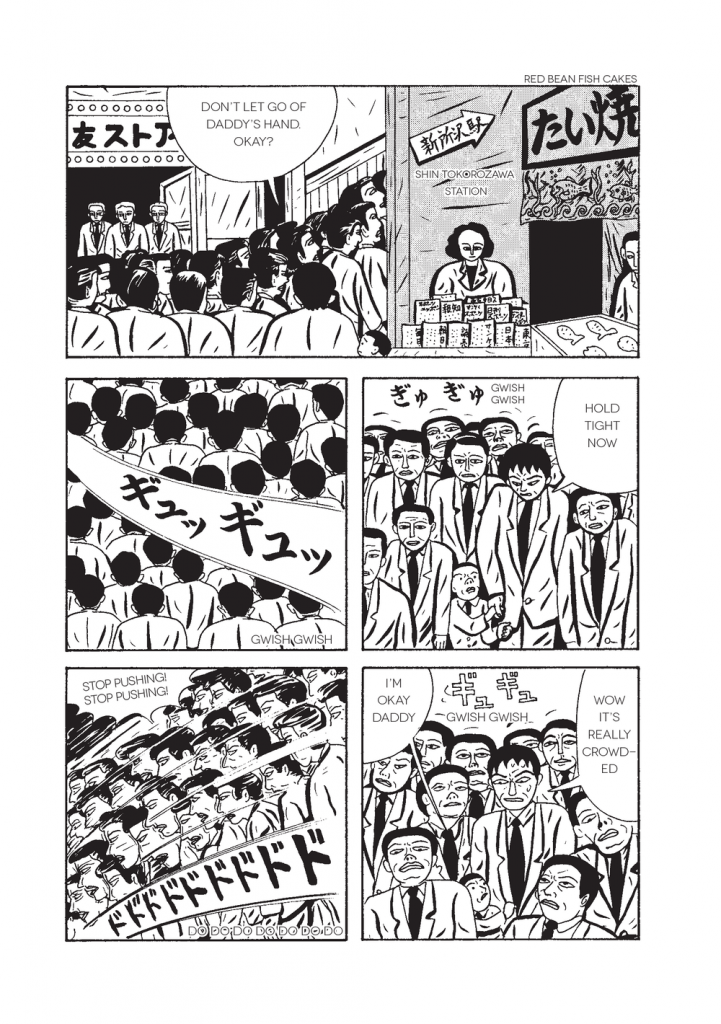

Seemingly transmitted from beyond the borders of reality itself, yet anchored recognizably within it, the stories that make up neo-manga master Ebisu Yoshikazu’s collection The Pits Of Hell (originally published in 1981, finally translated into English for publication by Breakdown Press at the tail end of 2019) are unlike anything else ever seen, and very much live up to the book’s name. They’re very much an acquired taste, perhaps best suited to those capable of locking their consciences away in a strong box for a time a la Ruggero Deodato’s Cannibal Holocaust or Mike Diana’s Boiled Angel. But unlike those deliberately transgressive works, there is, at the very least, a reflective, if something less than redemptive, quality to these stories that gives them a degree of social, even philosophical, relevance. It’s a book that will shock you on any number of occasions — but crucially, it will shock you into thinking, rather than just leaving you directionless and reeling. Written and illustrated in a deliberately spartan style that is brisk and no-frills, it is true that the matter-of-fact nature via which Yoshikazu communicates the surreal and extreme takes some getting used to. That said, the horrors he depicts are all too relatable for many, depicting the emptiness, even, at times, the self-destructive nature of city life, working life, school life, family life — hell, life in general. If you’re wondering what the titular “pits of hell” are, you’ll no doubt be heartened to know that they are the world around us in all its dysfunctional, pointless, degenerate hopelessness. “The End Is Nigh” is a sentiment for those who still need some distance between themselves and the abyss — this book posits that the end silently, inexorably hit us long ago, and we’re living through a kind of intellectual and cultural post-apocalypse.

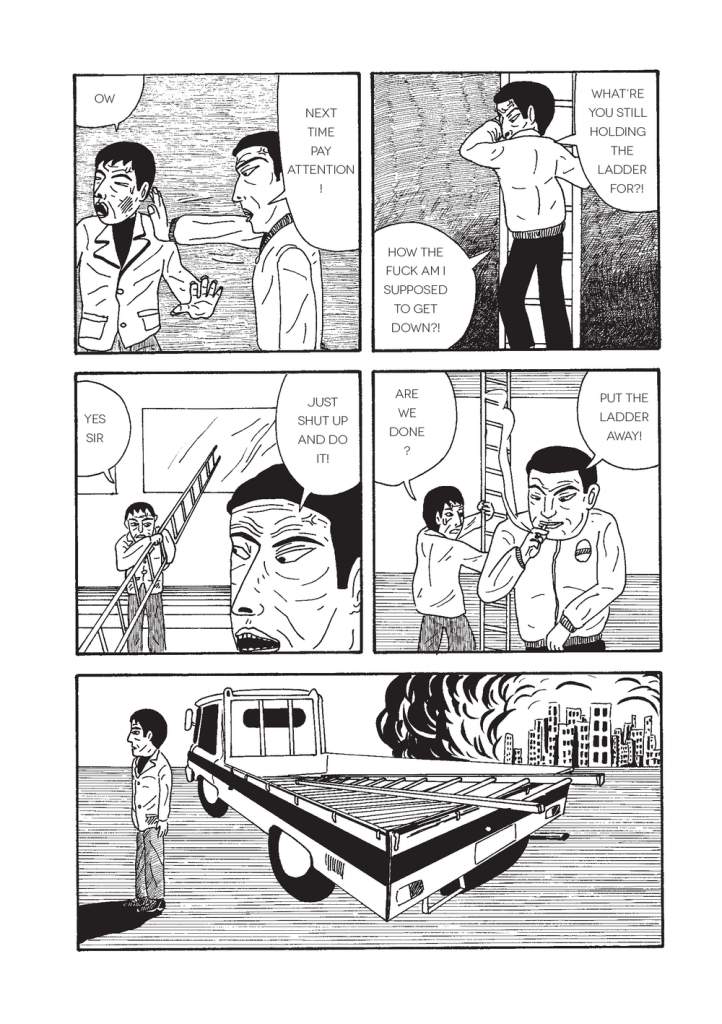

The disillusionment and nihilism that are Yoshikazu’s stock in trade affect people from all walks of life, regardless of circumstance and economic status, and while it’s fair to point out that all of his protagonists are men, they’re men from all quarters of society: put-upon schoolteachers, put-upon students, put-upon worker drones, put-upon bosses, and especially put-upon gamblers, a segment of the population he trains his sights on no fewer than three times in a nine-story collection. This might seem like overkill, sure, until one considers that Yoshikazu was himself a well-known gambler (as well as a television star and father of three) and that he worked as a poster artist in his youth, an occupation shared by another of his protagonists.

So — how much of this is autobiographical? My guess is just enough to pull the material down to Earth. Yoshikazu probably bet on a fair number of boat races when those were a big thing in Japan, for instance, but controlling them through telekinesis, as his nominal stand-in does, would clearly fit into the “you wish, buddy” category — which might also be extended to the idea of smashing in “his” boss’s skull with a hammer in front of all his co-workers, or decapitating a rambunctious youth (violence to the head is a recurring theme in these pages). One can only hope, however, that there’s nothing of the artist himself in the story about a beleaguered CEO who murders his wife before doing the same to all his employees.

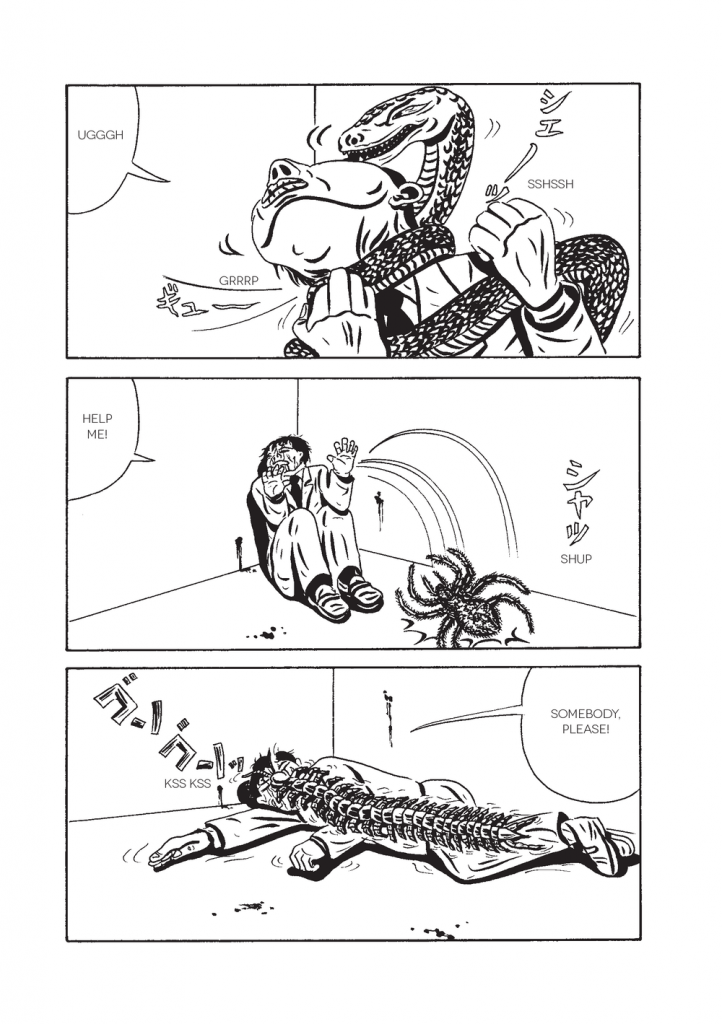

Much of the horror on offer here is more outrageous, surreal, and largely-metaphorical, though — and bizarre as it may sound on paper, that’s actually a bit of a relief. The various and sundry animals and creatures attacking the downcast suit-and-tie worker in “Salaryman In Hell,” for instance, are clearly stand-ins for the numerous and all-encompassing physical and spiritual and emotional dead-ends in his life, and while the utterly casual nature of their absolute ruthlessness is unquestionably disconcerting, it appears at a juncture in the book’s “running order” by which we’re pretty well used to such things, and the added layer of batshit insanity adds a frisson of gallows humor just when it’s probably needed most. The overall tone remains constant, but the shift in methodology is welcome, if temporary.

It has to be said that the cartooning remains pretty constant throughout, though — sparse on the backgrounds, sparse on the differentiating characteristics from person to person, sparse on the variety of facial expressions. This probably sounds more critical than I mean it to be, however: Yoshikazu is by no means the most technically proficient of manga artists, but his uniform style fits the uniformity of his themes and narrative tone. It can get a bit repetitious, sure, but deliberately so, and, as a result, there’s a kind of hermeticism to the storytelling here that works well in all its facets.

As much as this is a “your mileage may vary” work on the whole, though, one piece of advice is consistent for any and all audiences — read the backmatter. Not only for the typically superb essay by translator/project co-ordinator Ryan Holmberg but for the insightful afterword by Minami Shinbo and the notes on each strip provided by Yoshikazu himself. Putting these stories within their historical and cultural context is very near essential to fully forming one’s opinion of them, and, while some details may come as no surprise — such as the fact that most of these stories originally ran in the pages of the legendary Garo — others are genuinely surprising to the point that saying more about them would be saying too much. Suffice to say that Yoshikazu’s entire career inside and outside the realm of manga had a way of cross-pollinating with itself, and much of that is reflected not only in the subject matter of his stories, but in their overall structure, which often feature no discrete beginning, middle, or end, and have a habit of circling back on themselves in ways both foreseen and decidedly less so.

As challenging to readers’ stomachs as it is to their minds, aesthetic sensibilities, and preconceptions, The Pits Of Hell is a truly singular manga. You may like it or you may hate it, but one thing’s for sure — you’ll never forget it.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply