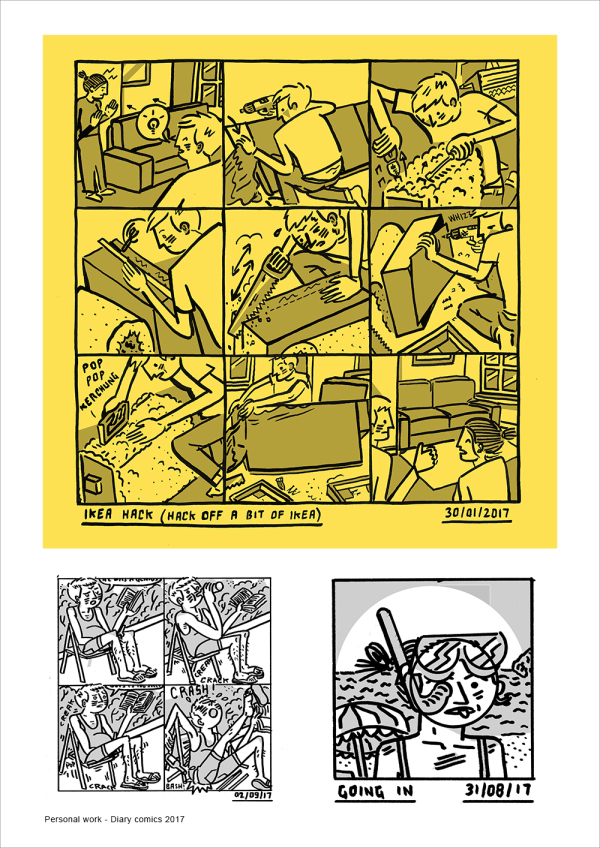

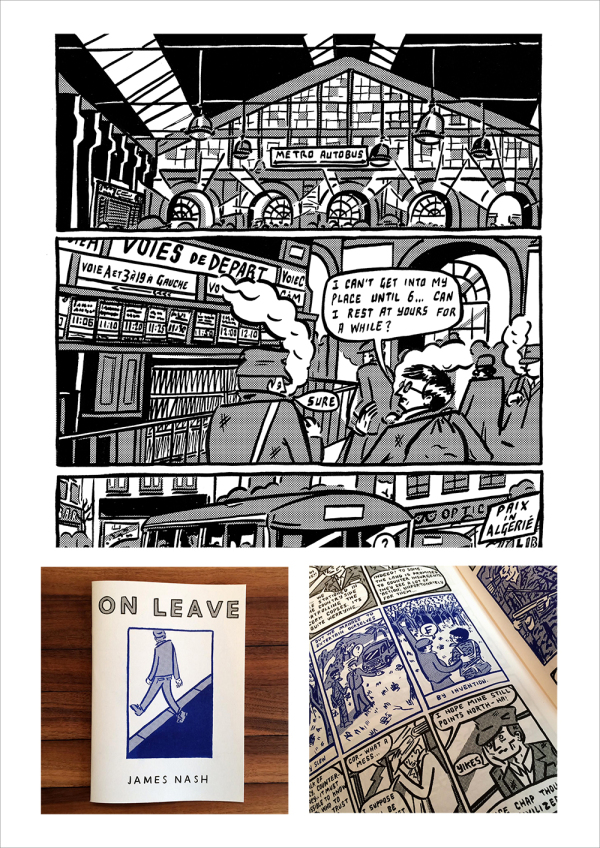

James Nash and Paul Ashley Brown are two British comics auteurs renowned for blending autobiography and imaginative realism. Nash has been self-publishing for around ten years and has placed himself into much of his work. One of his first projects found him recording his life, day by day, three panels at a time, for an entire year. His colour style varies, but his signature energetic and deceivingly simple ink line is notable across all his work. While speaking to Nash about his love of risograph printing for another article, he kindly forwarded me some of his Ashley Brown collection.

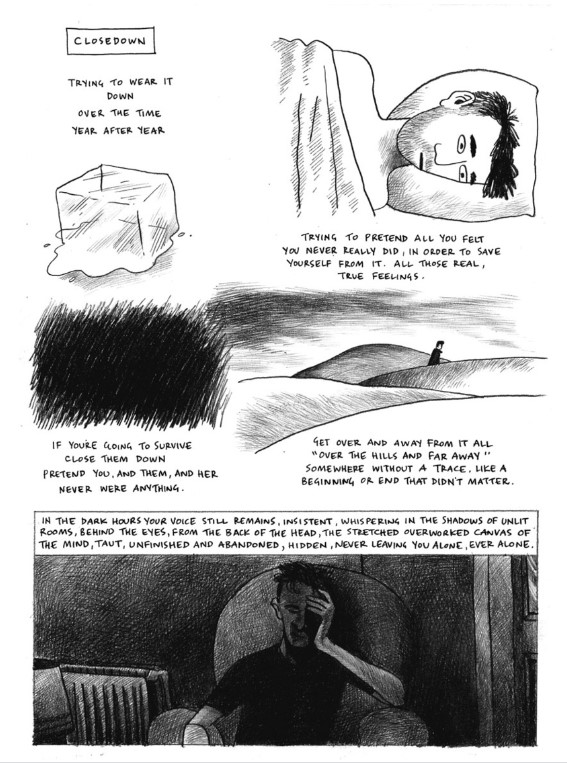

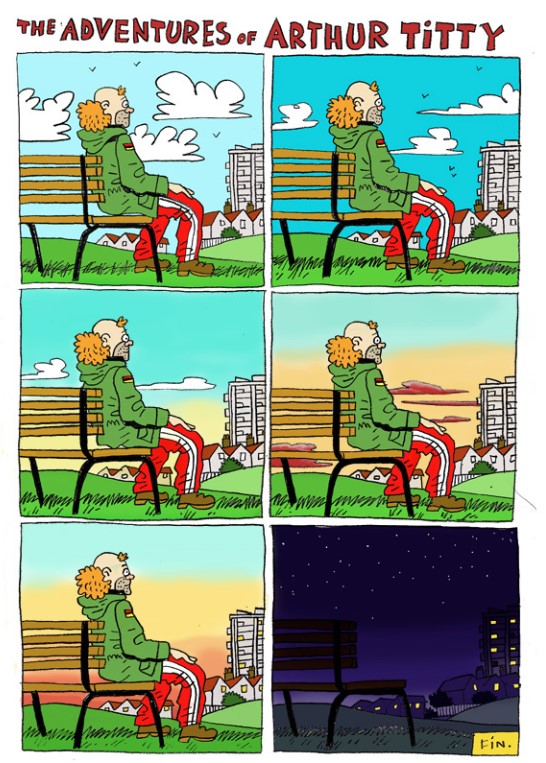

Brown first got involved in comics in the early 1980s, but took a sabbatical in the 90s before returning to the practice after graduating with a degree in illustration in 2001. Since then, he has built a reputation for producing enjoyably miserablist works that boast stretchy, tangible characters and fit snugly into the British social realism tradition. Brown also goes by the name Milo Tindle, a reference to the 1972 film Sleuth. He has also employed satire, such as in the recent Bonbon Fabrika, for which he gloriously bastardised Disney icons.

Knowing that the pair are supportive of each other’s work, I thought it a good idea to bring them together on an electronic settee for a cosy and rambling chat about making comics, reading comics, the British comics scene, and being open to the possibilities of stories. The common theme which appeared during our talk was their reliance on keeping an eye on seemingly unimportant moments and fleeting strangers as a method for capturing life’s minutiae in their work.

Nick Burman: I wanted to start by asking how you met? What was it about the other’s work that drew you to the other?

Paul Ashley Brown: I think we were both at the Handmade & Bound Zine Fair in London around 2008-9, each on separate tables trying desperately to whore ourselves to a vaguely puzzled public. Well, I know I was. I think James may have been more successful. I was a scowling old git with a club foot and a cynical cloud of melancholy gloom hanging above my table.

James Nash: Yes, I think it was at one of those fairs at the St Aloysius Social Club which were wonderful, and gave rise to the Alternative Press Fairs just after. It was people doing all kinds of stuff, not only comics, and the event had a really positive, supportive atmosphere.

Paul: I remember being intrigued by the format of James’ work. His was a long, tall zine, and I loved the wonderful honesty of it. His daily, three panel format had ended up encapsulating a whole year of his life. I thought the discipline was admirable, but the frankness, directness and honesty of the contents was the thing. It was a life you became drawn into and along with via the brushy immediacy of the artwork. It’s a work that I constantly reread and revisit, and has got stronger and finer as time’s gone on. I was so enthused I wrote a small review of it for Terry Hooper’s website. After that, we’d bump into each other at similar zine events and grouch about why we weren’t yet famous comic geniuses, while James batted off a continual gaggle of simpering admirers, and I fought off the usual slew of drunks and ne’er-do-wells in the car park outside. Happy days!

James: Early on I’d share a table with my friend Matilda Tristram (check out her comics!). We’d speak a lot to Paul Gravett, who was very excited to tell us about Paul’s work and had known him from years previous. Paul was making one-off hand coloured original comics and selling his Browner-Knowle zines at the time.

I do remember making a few good friends and creative allies from that scene, particularly Paul, and being excited to debut new annual collections of my diary comics there.

Nick: I’m curious about your uses of alter egos and “cartoon-me’s” — what’s behind these comic versions of yourselves? And, leading on from that, how do you comic “in the moment”? Drawing seems, or at least may be considered, work which requires time, and yet diary comics and comics about experiences rely on the reader believing you managed to “capture” a moment the way a photograph might.

Paul: I don’t know if I think of it in those terms. I tend to put down what I observe, both outside myself, and whatever interior, emotional landscape one finds oneself in. Personally, I don’t want to create anything that isn’t being an honest insight into a current moment or thought. Though equally, I have also tried to produce work that isn’t about me, but might speak to something I feel is an emotional truth or connection. Looking for the stories of other people as well as your own, that you may have some degree of affinity or compassion with, is far, far more important.

I think in recent years, certainly in a lot of work that has come out of what is rather patronisingly referred to as “The Small Press,” there’s been a great weight of comics that are largely autobiographical, and a bit too self-obsessive/self-regarding perhaps. I admit to spending the last ten years being vaguely guilty of such crimes, to be fair. The best you can do is be honest in the words and pictures you put down, and be as compassionate as possible, and hope your work resonates somewhere, that some dialogue of hearts and minds can occur in the intimacy of a small room with your little book.

James: Like plenty of people, I read Understanding Comics whilst I was studying and it blew me away. Particularly the idea that the less information you give to a cartoon drawing, the more likely it would be ‘read’ rather than observed. Until then I’d been making a lot of overwrought graphic work. I liked the idea that collecting this minutiae in comic form, in enough of a quantity, might create some kind of empathy or shared meaning with a reader. This was pre-social media, before everything in the world was a collected quantity of minutiae in search of shared meaning….

Paul: As to drawing “in the moment,” I tend to do lots of observational drawing, or see certain people that will suggest an idea, or stories, or spark a phrase. Maybe it’ll be just a look in the eyes of someone I pass, and then you’re creating a whole life in your head about that. Some of the incidental one-page things I’ve done have been based on very specific incidents I’ve seen and noted at home. It’s very organic, and often waiting for the right time to sit and think, and draw. It’s solely about looking and feeling, and being open to the possibilities of stories. I think it used to be called “imagination.” Remember that?

That whole UK small press/zine environment was just so wonderful for about two or three years. It was just a very warm, lovely community of people that grew up around that time, that then managed to spread somewhat. I found myself in a similar environment to what I remember of Paul Gravett’s Fast Fiction table at Westminster Comic Marts back in the 1980s. Though I found the scene in 2008-09 a lot more diverse. It was a lovely thing to be immersed in again, a really positive space, full of so many lovely, talented, creative people. It’s no surprise it’s flourished, though also it’s changed a lot in that time. But what it is is such an important thing; that very grass-roots, DIY attitude. It’s vitally important to the medium. It allows new young artists to breathe creatively, and find their feet, and an audience, on their own terms.

James: My rule of making a three-panel strip once a day was a sound concept within which I could draw and describe whatever. If the drawing was bad then that was just an honest consequence of the experiment and equally worthy of it. It was really bad and contrived for a long while, but then I hit a groove that I felt was my own visual language and hopefully not too derivative of anything else. Over the few years when I met Paul I was getting a lot of response to my comics. I did get a bit of grief for the bilious and reductive caricature of myself that I’d created, including stuff I’d drawn in the moment about caring for my Dad in his last years, or callous things I’d made about a girl who I was heartbroken by, or my own portrayal of myself as selfish, depressed, and self-destructive become more acute within my comics’ reductive language, and really harmful without the benefit of hindsight.

Ironically, recent diary comics I’ve made have been more guarded and carefully constructed in their production, but have elicited almost no similar emotional responses. So there is definitely something about drawing “in the moment.”

I wanted to also say that Paul’s approach is consistently successful in capturing real pathos in a distinctive voice which is obviously his, but in that he rarely singles himself out as its graphic character. It’s skilled writing and also consistently looks great.

Nick: You both talk about your work being, in a sense, a therapeutic tool. I guess the internet is meant to be a more social version of these sort of direct interactions, but mistakes seem less likely to be forgiven there… There’s something about the page and printed work which encourages reflection, for the author and the reader.

On that topic, as you are both artists who have self-published, I want to create some space for the obligatory “we love paper” bit of an indie press comics interview… Why does self-publishing on paper remain important in the scene? What have your experiences been with digital distribution?

Paul: About what you say about it being a “therapeutic tool,” I’m not sure I’d agree with that idea. I don’t think it’s art as therapy. Art is Art. I think all art is about having a space that allows certain ideas to form and drift off in different ways, and for people to react in a myriad of ways. Art’s about looking at the world and transforming what you find in it into forms that hopefully tell you something about your experience of being alive, maybe in ways you’d not considered before. At best, on my good days, that’s how I like to think of it.

James: It’s good for the work to be made in the moment but not necessarily be consumed in that same moment. I also guess that whatever you write and draw might benefit from the context of the whole zine. Context is certainly missing on the screen, where something can certainly be, but where there’s too much stuff for you to be able to specify a relationship.

I’m a big fan of playing with format, my earlier diary comics were A3 folded lengthwise. I made some big broadsheet style ones including a pink one which was meant to be like a Gazzetta dello Sport but came out more band-aid coloured… My recent ones were made via risograph printing and I love its process, even just using two colours. Recently, for short stories, I’ve been appreciating the charm of the simple A5 folded zine, hot off the photocopier — the better the comic, the less physical frills it needs to have.

Paul: As to the value of printed matter, I think it simply comes down to the fact that people will always be interested in physical objects. Technology has changed the way we look and read. Our ability to take information in so rapidly, often in a split second, means we’re not really “looking” at things on social platforms and networks or screens. There’s a difference in something having a very physical presence in front of you. I think your response to it existing in the same physical space to you is very different to something you find on a screen.

The tactile quality of objects is also the thing. There’s a wonderful poetry and sensation to a book, or something handmade: the texture of paper, the smell of it, the fact you can hold it. It’s more of an immersive thing. As to zines, I find something quite lovely about the idea of buying a comic or zine from the person who made it, taking it home, and spending a moment enveloped in someone else’s thoughts and feelings. Those feelings may resonate with you, and tell you something valuable about the joys and sorrows of life. Life’s minutiae, as James said. The little truths we understand, but barely talk about.

If you go to zine fairs, what becomes apparent is the sheer diversity and invention of creativity within the medium. That’s so wonderfully inspiring. I love the times people who have never been to these things come along and get wrapped up in the possibility that they too can go away and create something. That’s proper art happening, giving people the enthusuiasm to find a creative spark in themselves. I have often found that aspect of the zine/small press environment more rewarding than people buying my stuff.

Nick: Paul wrote in 2009 (while reviewing James’ work, no less): “While previously the influence [on comics] was primarily the comic book world, and it’s own fandom, many of the new artists using this medium originate from the Illustration and Graphics courses around the country’s Universities.” This legacy has continued to grow, especially in abstract and experimental comics, where the lines between art book, art piece, and comic/zine are very blurry. Both of your stuff is very much story based, in that you draw characters and plot. The crossover and friction between genres, such as abstraction and realism, or drama and ambience, seems to be one of the core themes of contemporary comics. Looping back to the discussion on autobiographical work and “imagination,” such a push towards abstraction and surrealism also seems like a logical development for people uninterested in writing about themselves (or who perhaps don’t feel as if representation of people like them is lacking?). Thoughts?

Paul: I was aware while writing that the landscape of comics and who was making them had changed dramatically. Most young artists engaged in the zine environment were coming out of university courses and looking to get their work into the world. They weren’t necessarily interested in doing comics in the traditionally accepted way, if at all, and the small press “scene” afforded them a way of making work and building an audience. I’d seen similar attitudes in the Punk movement.

I’d done zines and comics back in the ‘80s, when I had wanted to be a “proper” comic artist (whatever that is!), and had tried to get work published to little or no avail. Beyond my zines, I’d only made a couple of things with publishers, one of which was an awful experience that put me off completely. I returned in 2008 after graduating as a mature student from an Illustration Degree course which made me rethink my approach to making comics and stories. I realised there was a new environment, that there were people using the zine fair as a way to create and experiment as much with form as context, and new approaches that simply suited them as creative people. And, of course, they push each other on with what they do. That’s the beauty of an environment that gets made in that way, and it happens sometimes because there’s a creative vacuum elsewhere, either in the traditional environments you’re supposed to go into, whether that’s illustration, graphic design, comics, movies, literature. Or because there simply is nowhere you can make that kind of work, unless you create it yourself. And then you’re going to change the landscape, hopefully, even if it may not be in obvious ways. Maybe a diversity of approach, and different ways of storytelling. But that’s what makes a medium develop. Taking risk and having the courage to go somewhere on your terms, and fuck what everyone else thinks.

James: It’s interesting to read Paul touching on the small press phenomenon from ten years ago, as that group has become the mainstream in what we consider to be comics today. Thanks again for that kind and incisive review Paul, I’d like to think it was reciprocated when I had the urge to post out copies of Bonbon Fabrika to Nicholas…

It has been interesting seeing that change in recent years. There’s definitely a thirst from visual communication and graphic design students to inject new energy into comics, and also to make the medium more accessible for themselves. The process of making a zine is perhaps the thing people play with and subvert. I definitely felt that during my time in self-publishing in Amsterdam that I was swimming against the stylistic tide. The younger people who saw my work not only ignored it but were actively standoffish about it at times! I suppose that, especially there, making stuff like what I do seems kind of antiquated, certainly not challenging or contemporary. That’s just my experience though. Representationally speaking, it is deeply uncool and unnecessary for someone like myself to be trading in on my perspective, I respect that critique too.

Bonbon Fabrika by Paul Ashley Brown

Paul: Is abstraction just a way for people who can’t draw well, to get away with bad drawing? I’m joking, but only slightly. Thinking of people like Richard Diebenkorn and Philip Guston, artists whose work I really like, who went from figurative work to abstraction… perhaps because they realised you have to say different things at different times in different ways. That to me does make sense. There are really no rules for any of this. To be honest, all approaches are valid I think, as long as they’re done well, and wanting to connect with people, and it’s not a load of self-indulgent masturbation saying nothing to no one. Also, I think we still tell each other stories because we need them. Fiction is often the only way you can tell real truths, funnily enough. Is all that matters finding a way to be humane? Especially when often our sense of the world is rarely that?

Nick: Abstract comics aren’t interested in “drawing,” and certainly not in cartooning. I love abstract comics, they seem to encourage you to find a story where there isn’t one (in the traditional sense). I recently wrote two articles, one on riso printing and the other on internet aesthetics in comics, and they both sort of came to the same conclusion: that while artists are dealing with and utilising very mathematically precise digital illustration tools, there’s also this need to be make that art tactile through relatively labour-intensive printing methods such as riso, where the outcomes are indeterminate. It’s a dialectic between the material and the seemingly immaterial.

James: I love abstract art, especially in painting. I’m a big admirer and wannabe student of graphic work and typography and love to experiment with riso printing methods. Those things aren’t comics by themselves, but it’s cool to think of their potential influence in comics. As I attempt to write and draw better comics, I’ve found that my appreciation for coherent narratives, that lean neither too much on text nor graphics in their method, only continues to grow. The thing about good comics is that they’re almost too easy to read!

I really love Dash Shaw’s recent work for this. It’s so well written that its aesthetic seems like an afterthought almost, but stronger aesthetically for being that way.

Paul: About abstraction with respect to how those ideas are changing comics: as I said, I do think any way of thinking about the medium that takes it into different directions is valid. If we think of comics as being a language, which they are, a combination of visual and literary information that collides and caresses, then it’s no different to any language in that it can be incredibly elastic and ever-changing. It has codas and rules, but they change over time and in relation to who uses the language.

I personally find a lot of the traditional methods of comics and how to think of them as being somewhat stifling, all those panels endlessly repeating for instance. I’d rather think of comics like music and poetry and memory, whereas normally people make the very tedious and lazy comparison to film, which is something very linear. I don’t think we work like that necessarily, so why make comics seem like that? The possibilities for where and how stories move in comics is endless really.

Nick: Let’s get on to other comics artists and books you’ve been reading. What have you been obsessing over recently?

James: Aside from Dash Shaw, I’ve been lucky to know other people from the comics fair scene who’ve gone on to do really cool stuff.

Antoine Cosse especially is a genius I think! Lizzy Stewart also, Luke Healy’s stuff is really good… While I was in Holland, I was introduced to all the insane comics of both Michel Budel and Maia Matches, whose works were a revelation! Also, Japanese artist Saki Obata is great, I’ve been collecting all her zines for a couple of years.

Like Paul, Jaime Hernandez is my favourite ever, Just off the top of my head, work by Tim Hensley, Joost Swarte, Archer Prewitt always stuns me.

I try to keep it all at arms length a bit so as not to be too influenced and/or insanely jealous of my peers, otherwise I wouldn’t make anything for feeling defeated… So I also take in a lot of fiction, art, films and music too.

Paul: As to what comics I obsess over lately. I rarely obsess over comics these days. I don’t really buy comics anymore, as there are very few that truly interest me. I personally find most of them visually boring, to be honest. I often can’t get past the art if I think it’s awful. There are certain people within the zine/small press environment whose work I really like, not just because I’ve got to know them, but because I love their work. People like James, Simon Moreton, Alex Potts, Lord Hurk, Dave Lando, Jayde Perkin, a few others. I’m always glad to see them doing new work.

As to the wider comics world, I think Eleanor Davis is astonishing. Everything she does is just staggering really. The best comic artist out there I think, the one artist I do think that can be considered a “graphic novelist,” if I were forced to use that dreadful term. I mean it in the sense of her scope and breadth of subject matter, which is akin to a literary novelist. Tillie Walden is pretty great — On a Sunbeam was a wonderful book. Her other work is equally beautiful and moving. Jon McNaught’s books are lovely. He understands the poetry of the quiet moment and stillness better than most.

Nick: I totally agree on the “comics are not linear” thing. I’m often referencing Thierry Groensteen’s description of comics as being primarily about the arrangement of things in space, which is how the comics page can do all sorts of strange things in terms of narrative time and associative logic.

Paul: Oh, I like that description. I tend to think about comics as a language which primarily requires a certain compression or reduction of forms within space often. You have to understand spatial composition, and how to compress words, fragments of image. It’s about editing out a lot of the time. Good cartooning is essentially always about that, too. Reduction was something I was interested in when making my Browner-Knowle zines. What is the essence of a story, or the fragment that tells you enough for you to create the rest in your head as a reader? Cartoonists play with levels of abstraction, and leave the reader to do some work and, as you state Nick, make associations that may not be explicitly provided.

A lot of my stuff doesn’t feature “whole” narratives, with beginnings, middles, and ends. It’s mostly moments, incidental stuff, that hints at a larger narrative perhaps, but sometimes doesn’t. Sometimes it’s more about trying to create a mood or feeling that resonates rather than create a story in the conventional sense. It’s why I like thinking about how poetry and music and lyrics work. I remember reading an interview with Lorenzo Mattotti where he stated something along the lines of looking for a deeper feeling, a poetry in comics: can it be found? That always stuck with me. Again, the medium has huge potential for saying so much about what it means to be alive, sharing things that tell us about who and what we are. There’s been a huge shift, with more diverse stories and voices coming to the fore in the last 20 years. That can only help expand comics’ parameters and appeal.

Nick: Both of your works remind me of “poetic realism,’” a phrase I’ve heard in relation to recent in British film culture. I guess it could be summarised as a slightly more literary, somewhat meta evolution of the kitchen sink genre.

Paul: When I returned to making zines and comics, I was aware that being older, and having studied illustration, I had begun thinking of different ways of telling stories using pictures and words. Illustration made me think differently in terms of what you may be attempting to communicate in a single image, rather than a succession of images like comics. Sometimes you’re just not ready as an artist, or a person. One time it’s not the right time, and then it is. That’s also become the way I approach my work. Sometimes it pays to wait, to be quiet and still.

The Smiths were a huge artistic influence — does that make sense? A bruised, everyday poetry of Working Class Romanticism. What are the riches of the poor? For me, it could be paper and pencils and a decent cup of tea. And endless unrequited longing. Those have been the only constants in my life, the beauty and poetry of ordinary life. There’s nothing meta in that I’m afraid. But there’s always beauty and poetry and art to be found. It’s all in the seeing and feeling, isn’t it?

James: I definitely love the working class romanticism vibe in Paul’s comics. I had a big walk through the Bedminster area of Bristol recently, and I felt that I was inside an issue of Browner Knowle. There there are rolling, hilly streets populated with scattered, desperate characters, separated by roaring arterial roads. Paul’s bold pencil drawings are so evocative of that.

I grew up on a Wolverhampton council estate but don’t really make work specific to it. I think my upbringing is just this thing that’s at the core of my perspective and how I describe things. I was always aware that there was a world outside of it and my obsessions with skateboarding, art, and music opened that beyond up to me. Most people where I’m from think I’m a pretentious idiot, but I still love them and the place. I’ve been making a story that juxtaposes some of those things, like the time someone threw a snake through our window, or the time I got a knife pulled on me while skateboarding past the “wrong” house, but I’m not sure what the voice for that work is yet. I’d like to think that my perspective and politics are at the core of anything I make, especially my visual language, but I’d also prefer to look forwards and explore new things.

Nick: I wondered if we could touch upon the “British tradition” in cartooning. If such a thing can be said to exist. From my perspective, it’s mostly split between satire and domestic settings, though those are often together too. The combination seems quite close to the root of the “working class romanticism” you describe. Actually, I think those two types work themselves into British TV and cinema and novels as well. Do you feel anything about the conventions and the styles your national environment has imposed upon you?

James: Having spent six years living outside of the UK, considering it from the outside before moving back, I’ve really come to appreciate its conventions, its anachronisms with regard to culture, class, and the landscape it engenders. I think cultural products strive to capture what that is, but I don’t feel that it’s something that imposes itself on you as a writer or an artist, or that there’s a “style” to conform to.

The differences that are imposed on us politically and through Britain’s tiers of inequality are the things that drive the kinetic energy in its culture.

Paul: I’d agree with what James says. I think if you’re any kind of artist, you soak up everything around you, though a form of cultural osmosis. Some things get embedded within you without you seeking them.

I grew up in the UK in the 70s, culturally and politically, it was a very radical and polarising time. I feel incredibly privileged to have grown up when I did, in the 1970s before everything was ruined by Thatcherism, before the world became completely obsessed with selfishness and the needs of the individual over the community or society. I found things like Punk and Post-Punk very exciting and liberating. I loitered shyly and awkwardly in political environments associated with those movements, things like Anarchist-Punk, Crass, Class War, and feminist arguments that had emerged from the 60s and amplified through the Greenham Common movement. These were fantastic dialogues that I guess informed my thinking.

Television then was more diverse I think, and quite mad, and offered incredibly interesting singular voices and opinions. There were very good writers who had a wonderful darkness, people like Dennis Potter and Nigel Kneale, who wrote odd, poetical things. British comics was a very odd place to find very odd stories. And then there was 2000AD, which seemed to tap into a social zeitgeist, and continued a certain thread of off-kilter anarchy, a satirical rebellion I had found earlier in the likes of Leo Baxendale and Ken Reid, Ralph Steadman and Gerald Scarfe, plus glam rockers such as Bowie and T-Rex, and the punks and new wave artists. This period produced a continually opposing and dissident voice, one that refused to kow-tow or doff its cap to supposed betters. That all interested me.

Nick: On more practical terms, how do you two actually go about affording to print, visiting fairs, etc.? Is it just a case of having a “proper” job and then subsidising your passion, or is there any money to be made from being a storyteller? I’m asking this question for the benefit of the young and budding artists who may be reading this and looking for some suggestions regarding how to sustain their talent.

James: There are certainly more financially rewarding things that you could do! I’ve always had to work alongside making comics. But then again, I know plenty of people who’ve had more success. It also depends to what degree your comics practice bleeds into your other revenues of income, such as teaching, design, animation, writing, etc.

It’s a wonderful thing to cover your production costs through sales and commissions, and who knows what putting your work and ideas out there might mean for you.

Paul: Ha! Yes, I have a “normal” regular job, four days a week. Which finances my printing costs, table costs at fairs, and materials to make drawings and comics and zines.

If you want to make money, don’t do comics. Anything you want to do you’ll probably have to attempt to find funding for, whether that’s through things like Kickstarter, or Arts Council funding, or Grants if they’re available. If you’re lucky, and what you do ticks certain artistic and thematic subject-matter boxes, you can probably get a graphic novel deal these days, as that’s seemingly the only valid way you’ll be taken seriously or have any visibility, irrespective of whether that’s artistically or financially worth your while. The one subject everyone avoids discussing is the economic value and worth placed on and by artists in the medium, and for me, it’s the subject that requires more transparency and discussion.

We may well value the creative and cultural significance of the medium, but I’m incredibly doubtful and cynical regarding how much of that is reflected in the economic situation a great many artists find themselves. So much of the landscape we’ve discussed seems, certainly from where I stand, a cottage industry with little real financial support or providing many decent livelihoods. Yes, there are a lot of publishers out there, and it seems that “we’ve never had it so good,” but I often feel in an emperor’s new clothes sort of situation.

For those “young artists” out there, my advice would be nothing to do with money, other than don’t do anything for free. And everything you do, or as much as you can, do on your artistic terms, even if that may mean narrowing potential opportunities. Try to have as much control over your art as possible. Try and create your own space and your own voice, even if it flies in the face of what’s supposed to be acceptable or commercial. Have a sense of your own value and worth as an artist and person. If you don’t, nobody else will. And just keep going. There will be someone somewhere who will not just “get” what you do and why, but they will also like it, and want to know it, and stay with you. If your art can speak to someone, that person will always want to be part of that conversation. To me, that is what it’s really about.

I guess I’d ask: “What do you want me to know of you, and your art? What do you want to tell me and share with me about this living thing we’re trying to cope with?”

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply