Author’s Note: I wrote an essay about Peter Gallagher’s Heathcliff comics which was published on SOLRAD in April, 2021. The day it was published, a friend let me know he was buddies with Gallagher, and within hours, Gallagher and I were corresponding via email. He agreed to a phone interview, and I compiled a list of topics to refer to when I inevitably started rambling.

Gallagher was friendly and easy to talk to; when he answered the phone it felt like we were continuing a conversation we’d been having for years. There’s more of me in this piece than I’d intended, so up there in the title, I’m calling it a conversation rather than an interview. I think that’s alright, though. If you enjoy reading this conversation half as much as I enjoyed having it, it’s a win.

Thanks to Casey Burns for the introduction.

Peter Gallagher: Andrew, hey.

Andrew Neal: Peter, how are you doing?

Good, good. How about you?

I’m all right. Thank you for agreeing to talk to me for this thing.

Oh, yeah, I was kind of blown away by your article. It was really great reading.

Well, I appreciate you saying that. I was hoping that you would see it, and hoping you would understand my reason for including all the different viewpoints on it. I felt like the intent was pretty clear, but you never know.

Yeah, definitely. I don’t know, sometimes you’re toiling away and with social media, you get to see reactions to things. But sometimes you’re doing stuff here, and you’re just hoping that people are understanding what you’re trying to do. [The SOLRAD Heathcliff Week essays] really were great. I really appreciate that.

Thank you very much for saying that. You know, I haven’t done a ton of stuff like that. But I feel like when I connect with something – it’s probably true for everybody – if I connect with something, then it’s a lot easier for me to write about it than if it’s just, hey, here’s a thing out there in the world.

Right, right.

So I think clearly, people are connecting with your work. Not everybody, because everybody doesn’t connect with everything. My intent with the essay was a response to the fact that so much of what is said about Heathcliff is just, “Hey, that’s weird.”

Right.

I just kind of wanted to say, hey, there’s a way to talk about these comics without just saying, “This is weird,” over and over and over again.

You know, it’s funny… On Twitter, there’s the guy who does the “Actual Heathcliff Comics” account, and it’s just gotten huge amounts of attention, which is great. And then there are a couple of other ones – and I appreciate anybody who’s doing stuff – but there are guys who are just taking random Heathcliff comics and putting different captions on them. So they make absolutely no sense. I’m like, “Hey, come on.”

Yeah.

I’m not just doing stuff that doesn’t make any sense at all, you know. I mean, it’s kind of funny to see that, but it’s also a little bit like, “Wait, I don’t want people to think that’s what I’m doing.” You know?

Yeah, you kind of have to let it go out into the world and do what it does, but I feel like that definitely indicates a kind of a lack of understanding on their parts. Their messing with your comic in that way is almost like someone trying to speak a language they don’t understand. You know what I mean?

Yeah.

Like, it’s almost like they’re trying to communicate back to you, or maybe just saying, “Hey look, I can make a Heathcliff too,” but they don’t get what you’re doing or how to do it.

Right.

It’s like they’re catching a piece of it, but not the whole thing. And, by the same token, there is a bit of an opaqueness to what you do, which invites that misunderstanding in some ways, right?

Oh, yes.

You’re not explaining it, you’re just putting it out there. You’re not saying, “Hey, here’s what my joke means, guys.” I feel like there has to be a level of acceptance on your part if you’re putting something out there. It’s basically just a question of the conflict probably most artists have. You have to accept that people are going to interpret it the way they interpret it, but you also don’t want them to get it completely wrong.

Yeah, I think so. I mean, it’s funny, because when I started doing Heathcliff, I was studying under my two uncles, George Gately and John Gallagher. And sometimes if you look back at some of the old ones, it was always a little bit offbeat. But it was traditional gag writing. And it was great. I mean, I was learning. I felt like I was going to graduate school for cartooning, you know, and before I ever took it over, I did maybe four years of what I would consider an apprenticeship.

Right.

I was writing ideas, they would accept certain ones, they would talk to me then, and then I remember them saying, “Look, Heathcliff’s been around for a long time. What you’re going to do is ideas that we’ve already done. That’s the first thing that’s going to happen. We’ve done so many ideas about a cat cartoon that you’re going to repeat, and so we can’t use those.”

Yeah.

But after a while of doing it, I always think the fine line that you walk, when you’re writing gags, you know, is over-explaining it. If you over-explain it, you ruin it. If you under-explain it, then people are confused, and they don’t know what to do. And after doing it for a number of years, that’s the thing that I’m always concerned about: the amount of explaining and over-explaining, and I think I’ve decided on the under-explaining. And it’s a daily comic. So if you don’t understand this one, I hope that if people read it on a regular basis, maybe they’ll kind of start to understand what’s going on with it.

Right. That all makes a lot of sense. It’s great that in working with your uncles, that was one of the things they told you: “You’re going to repeat us because that’s how this works.” That exhibited an understanding of what they were doing. And it was just a fact. If you’re working on something that isn’t yours initially, if you’re trying to emulate what’s been done before, you’re by necessity going to copy, right?

Without a doubt.

So is that really when you started cartooning? Or were you cartooning before you started working with them? Ever since I was in kindergarten or so, I always drew. I drew almost every day. It was like my favorite thing to do. I loved sports and playing with my friends and stuff, but I would sit down, usually in front of the TV, and draw. I have an older brother who’s a musician, he would like to sit and play his guitar, you know. But I would draw. I would always have to have a piece of paper and just draw cartoons. And I would draw all kinds of different things. I even had my own comics group, like Marvel, when I was a kid. And my younger brother had a rival comics group, you know, and, and we had our own superheroes and stuff. But I was always drawing. I was always drawing.

Right.

We got the newspaper every day. We got the New York Daily News because we lived in New Jersey, and I loved reading the comics. And I would try to draw BC comics by Johnny Hart. That was one that one of the first ones that I started trying to copy the drawing style of.

Okay. You mentioned the superhero stuff, but it sounds like the comic strips were definitely a huge thing for you from the beginning.

Yeah, yeah. And also there were my uncles, my dad’s family. My dad was the youngest of three boys. My dad was a lawyer, but my two uncles, George and John Gallagher, were both cartoonists, and they were kind of famous and I remember as a kid going to their house. And it was really cool – not the fame part of it, just seeing that this was their job. They each had a studio. And I used to try to sneak into their studio –

Ha ha ha!

– and you’d see like, all these cool pencils! They would have tons of pencils. It’s one of the things that I do in my studio, I buy so many pencils, and I just have tons and tons of them around my table, I think just because it looked so cool to me.

Right!

But my dad would try to discourage me from going in there. He’s like, “Hey, that’s where they work!” But I loved going and looking at what they did.

It is where they worked but they were working on something fun.

Oh, yeah.

I mean, it was cartooning! So that was definitely one of the questions I wanted to ask you, if being around them was a big important part. And clearly it was.

Yeah.

The strip itself started in ’73? Is that correct?

Yeah, that’s right.

You were a kid?

Yeah, I was probably in third grade or something like that.

About 10 years older than me then. I’m 46.

Yeah, I’m 54.

Okay, was Heathcliff something that you were particularly aware of as something that they were working on, or was it just George working on it at the time? I don’t know what the timeline is.

Yeah, when I was probably around that age, I knew it was in the newspaper. It wasn’t like I aspired to take over the stuff at all. I just loved to draw. It was almost like a compulsion. Like, up until maybe high school. I still was drawing in high school. But before then, when I was like in grammar school and younger, I felt like I had to draw every day. If I didn’t draw, if I missed a day of drawing, I felt kind of uncomfortable. I don’t know, I felt itchy. I just had to do it.

I understand that! I didn’t start drawing comics until later in my life, but I’ve always drawn. The way I made it through classes in school was drawing in class –

Ha ha ha!

That’s just the way I persisted, and as long as they didn’t require me to turn in a notebook, I did okay. So I definitely identify with just needing to draw.

Yeah.

So you apprenticed with them, and when you started working on Heathcliff, that was the late ’90s?

Right. I think I maybe started working with them around 1994. You know, they were kind of getting older. And then in ‘98, I took over drawing. Before that, I was doing ideas. It was my two uncles, and another guy Bob Laughlin, who was their inker. It was the three of them doing it, and they would use my ideas. I would see my ideas published, and it was really exciting. But then, the big leap was drawing it and getting their drawing style down and laying it out. Like, that was really time-consuming and hard work. When they decided to retire, it was like kind of being thrown into the deep end of the pool. When I first started, I don’t think my drawing style was up to snuff. Back then the syndicate used to mail us a proof of a week’s worth of daily comics. I would get that in the mail every week, you know, and it was hard to look at because I knew it wasn’t good enough.

You were judging your stuff against your uncles’ stuff.

Oh, yeah, yeah. It was like, “oh, man.” But I tried not to worry about it too much because I did feel like it was getting better. So I was like, “At least I’m getting better. Try not to look at that and judge it too harshly. Just keep working on getting better.” And then I was able to start doing it faster and better. And then, even adding my own twist to it. Trying to maintain that style, but also getting my own drawing style in it as well.

What I’ve seen of your work isn’t everything you’ve done. Gocomics has it starting from 2002. So you’d been working on it for several years at that point.

Yeah.

But there’s almost 20 years on there! It’s a huge amount. If you count the time that you were assisting and apprenticing on it, then I guess you’ve put more time into it than George did at this point.

Wow, that’s such a weird thing to think about. I would never think of it that way. When I started it had been going on forever.

But 1998 is 23 years ago, plus four years apprenticing on top of that, so 27 years total. George did it from ’73 to ‘98. That’s 25 years. You haven’t been the artist on it for as long as he was, but you’ve been involved with it for longer than he was. It’s kind of astonishing!

I’m astonished hearing it!

So you’re not the original creator, but you’ve been working on it for longer than most people work on the strips they work on, and it has changed over time. And you’ve kind of already said this, but you worked hard to emulate what it was before, and then slowly let your style in.

Yeah.

So the stuff that you’ve added to Heathcliff, was that something you wanted to do from the beginning? Or did it just kind of sneak its way in there?

You know, it’s funny. I always would say one of my biggest influences was probably Mad Magazine, all of the different artists and the humor. I would always do, like, very weird things that I thought were funny. And you know, when I was doing Heathcliff at first, I was really just trying to do a good professional job and trying to do professional gags. But as things were more online, I was getting feedback and stuff. There’s this website, The Comics Curmudgeon. The guy, Josh Fruhlinger, who does it, makes fun of newspaper comics.

Right.

And I would read it. And they never mentioned Heathcliff, they never made fun of Heathcliff. And I was kind of like, a little bit annoyed. Like, “What? I don’t warrant getting made fun of?” And they finally did, and then I kind of regretted that.

Ha ha ha!

He was like, “I can’t believe we haven’t made fun of Heathcliff! You know, like, now we’re gonna rip him to shreds every chance we get.” I was like, “Oh, no.” So, you know, they start doing that and there was this feeling of like, “Alright, you’re doing Heathcliff, you’re going to get attacked.”

Right.

And I was like, “You know what, I’d rather go down with my own humor than trying to be like, this middle of the road, kind of safe comic,” so it was good. It was a good impetus. I was starting to do that anyway, but then I was like, “You know what, I’m just gonna do what I think is funny.” Honestly, I’ll tell you, when I first started giving ideas and gags to my uncles, I would bring them a group of gags, like usually it would be like twelve or something. They would go through them and tell me “all right, not this one” and I was like, “Oh, I thought you would think this one’s really funny.” And they’re like, “Don’t do what you think we think is funny. You should do what you think is funny.” And I thought that was great.

That’s incredible for them to encourage you to actually change the humor of it.

Right. They weren’t so dogmatic. Their feeling was that I was working on it. I was bringing something to the table and I should do my own humor. I do think though, like when you asked before, was it gradual? I think it was. I think it was like I was trying to do a standard kind of gag writing and then throwing some of my own weird – or maybe not weird, but you know, my own – humor in there. And at a certain point, I was just like, “You know what, I’m just gonna go all in on what I think is funny, and we’ll see what happens.”

But you had to work up to that.

Yeah, right.

There was some internal conflict about it. I mean, it makes sense to me. I’ve only been drawing my comic for three years now. It’s all mine and still, every time I could feel it changing, I’ve kind of resisted at first. Every time I’ve let that happen I think it’s gotten better, but it’s not easy! I only can imagine the internal conflict and pressure when you’re changing a legacy comic.

Yeah. Right. All the time online, I see comments from people who are like, “Oh, he ruined Heathcliff, I used to think Heathcliff was so funny.” But, you know, at the same time, if I were doing the same ideas and the same humor that they were in the 1980s, I would be the worst comic writer. You know, humor does change, I think. it evolves a little bit.

It absolutely changes and evolves. And you can’t please everyone all the time, but it seems like comics fans, in particular, seem to have a very, I don’t know, time capsule idea of the things they like. They want repetition. And repetition is a key part of a newspaper strip, so that makes sense. The repetition of a daily strip is interesting. You don’t want to just repeat yourself, but to some extent you kind of have to.

Yeah, I think that you got it absolutely right. It’s funny, I teach some illustration classes at Montclair State University, which I graduated from, and I just fell into it kind of accidentally. I have this class that I’m teaching now this semester, and it’s just virtual. I had the students do a New Yorker cartoon, like just a one-panel New Yorker cartoon. But before that, I showed them this documentary called Funny Business on YouTube. And it’s about the history of the New Yorker cartoons, and they talk to the cartoonists now. I think it’s this guy, Mort Gerberg, who is one of the long-time great New Yorker cartoonists who talks about this idea. He’s like, “Here’s a cartoon I did about a cow.” he says that what you try to do is milk – not literally milk the cow –

Ha ha!

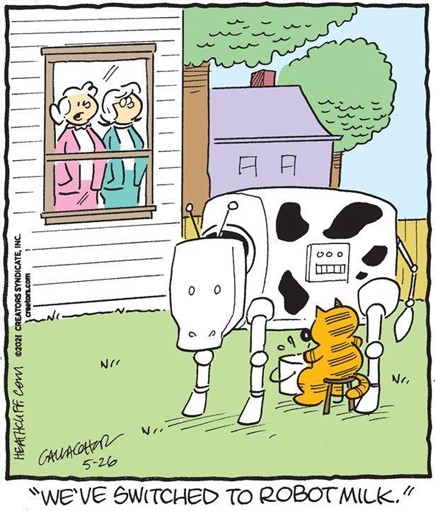

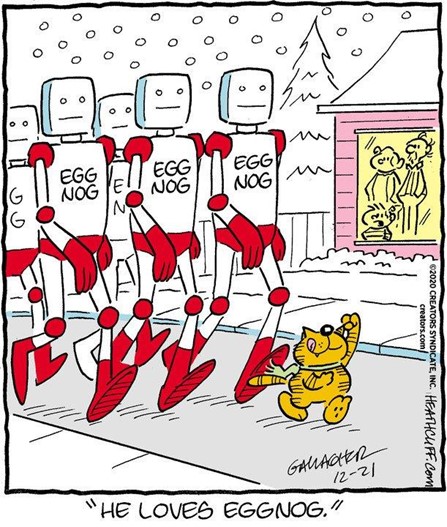

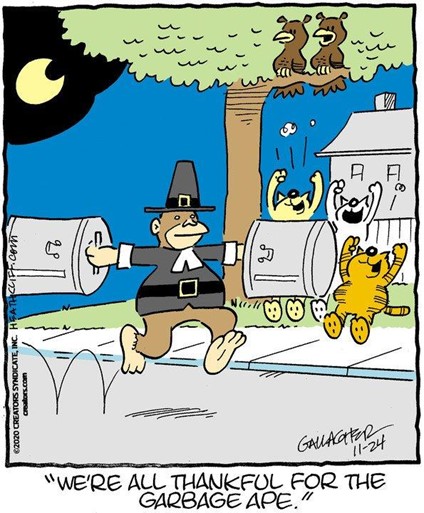

Like, you try to wring every drop out of a gag, and just keep going back to it and trying to get anything you can from and it’s true. I’m not going to do a helmet joke just to do it. Or, or even like the Garbage Ape, I don’t do the Garbage Ape that often because you want it to be funny, and you don’t want to overdo it. I think if you overdo it, it’s gonna ruin it and not make it enjoyable anymore.

It’s a fine line. Repetition is such an important part but you don’t want to wreck it. Now with these things that you repeat, like the helmets and the Garbage Ape, do you come up with an idea for something that would be fun to draw, or an idea that you think is funny, or what?

Yeah, say, for example, like the bubble gum, Heathcliff is floating away on it. Like, I might have done it one time thinking just the idea was funny. And, my uncles, before they were syndicated, with Heathcliff, used to do gag cartoons in the Saturday Evening Post, in like the 50s and 60s. And I have books that are like these collections of cartoons from the best of 1958, or the best of 1965. Not so much now, but I do go back and I look at them, and sometimes there’s just a drawing of somebody in the air. You know, something like that. I’m like, “Ooh, I love how that looks,” you know, and maybe I drew it with bubble gum. I guess it’s something that I think is funny or humorous, or I like how it looks in the cartoon.

With these repeating themes do you come up with an idea that you think will work over and over again, or do you just come up with something for one strip and then maybe go back later if you have another idea?

Yeah, I’m not trying consciously to do that. I’m trying to think of something recently like that. I’m not like, “I need a new repeating thing.” There’s one I just did, that’s going to come out in the middle of May, and I’ve done this a couple of times. I think maybe I’ve done one or two of this. It was in Heathcliff’s house. There’s a fish tank and there’s a lot of fish in it. And they’re all saying “bro” and they’re known as bro fish. So you see “bro bro bro bro.” The one that I just did was I have the bro fish again doing it and Heathcliff and Iggy are standing there and Iggy says “it’s a close relative of the dude fish.” And just the idea of having a million bros in the air was something that I felt was funny.

A lot of your jokes are really visual. Are a lot of them just based around things you think are fun to draw or funny to see?

Yeah. I sit down to draw, come up with ideas – you probably do the same thing – I just have a piece of paper, and I just start scribbling and sometimes writing words and drawing things. Sometimes you get an idea from just the things you’re sketching, like, a beekeeper or something. But yeah, I think it has to be kind of organic. I don’t know if you have the same experience, where there are times where you do something and you’re like, people are gonna love this and they don’t care about it, or the other side is you don’t think that much of one and they love it. It’s funny how you can think, “Oh, this will really go over big, and there’s silence.”

Definitely. For me, I have a very small readership, but one thing I’ve noticed is almost every time I draw a strip and I think, “Well, that’s just for me, nobody else is going to like that,” that’s the one someone reaches out to me about.

Ha ha! Yeah, you don’t know.

Now, what’s your process for making Heathcliff? Do you write and draw one comic and then move to the next one, or do you have days where you write and days where you draw? Do you do a week’s worth at once, or what?

Yeah, I try to do the writing first. On a day like today, I have to write stuff. Every week I’ll send six dailies and a Sunday to my editor. The daily writing you could say is maybe a different rhythm than the Sundays because Sunday is multiple panels. Sometimes I’ll find it easier to do the daily writing, and sometimes Sundays are easier. It varies.

That’s a good thing to have figured out.

One thing I found that’s interesting is that I’ll be working away at it and I’ll probably get four that are legit – like good, usable ideas – and then I’ll just go ahead and start drawing them. I’ll have four that I’m working on. Like I still don’t have two ideas, but I’m going ahead and I’m finishing the four that I have and as I’m doing that, I’m like okay, I still need two more. I’ve found that the times where I have those last two to do and the pressure’s on, and I just get them done at the last minute, for some weird reason those end up being my favorite ones. I don’t know if it’s the fact that it got pulled off at the last minute. Sometimes if you have a lot of time to work on something, you’ll use every second of that time, but if you’re forced to come up with something, you get it done, you know? I don’t know what it is, maybe the immediacy, but I have found that those one or two last ones when I’m under pressure end up being my favorites.

That makes sense. Sometimes with creative work the best stuff you do is the stuff you just have to get done. You just go ahead and do it, and somehow it turns out.

Yeah.

There are so many people, I think, who want to create something, and never create it because they’re wringing their hands about getting it perfect before they make it, which you can’t do! It doesn’t exist until you make it.

Yeah, exactly.

So do you still work with pen and paper as opposed to making Heathcliff digitally?

I do, yeah! I start with a pencil and on just a regular typing paper, or computer paper, and I rough it out in pencil. Then I have Bristol with the Heathcliff border printed on it for a daily, and I have a light table in my drawing table, and then I’ll ink it. I like the original pencil drawing to be rough because I’m not just tracing, I’m kind of drawing it in the inking stage, which I like. It’s like you’re leaving some stuff undone that you have to draw.

Absolutely! In my experience, if I do a pencil drawing that’s too good I’m going to ruin the inks!

Right. It’s so true! Yes.

If the pencil drawing is perfect, I know I’m just gonna wreck that thing.

Ha ha! Right, right. And I’ll just say one thing, too, about the idea of people trying to make things too perfect. When I first started doing this, the idea of doing a daily comic strip that has to be out every single day… You know, it was a little daunting. It felt like if you didn’t stay on top of this, it was like waves on the ocean just they would start crashing over you, you know. You’d just get obliterated. But that constant sort of need to get it done? Really, I found it to be very helpful because everything isn’t so precious.

Yeah.

It’s like, I care about these comics when I’m doing them, and then I scan my stuff, and then I clean them up in Photoshop, and then I email them to my editor. And then that night, usually, I’ll look at them digitally, like on my phone, just see what I did. And I like that, but then I’m on to the next thing. It’s not too precious. It’s just something you have to get done and do your best work doing it. And then you move on.

There’s something in the process of comics that means you can’t worry too much about the perfection of any individual drawing. Whether it’s comic books, or comic strips – even an ongoing single panel comic like Heathcliff, you have to be able to accept the drawings or jokes or whatever that aren’t exactly what you wanted them to be and move on to the next one because it can’t be about the one little piece of it, right?

Without a doubt. I’ll tell you a quick thing. I remember when I was just giving my uncles ideas. I would usually try to bring in twelve ideas. And this one time I just said to him, “I’m sorry. You know, like, I tried my best but…” and my uncle George Gately looked at me, and he’s like, “That’s the way it is. You try your best. You can’t hit a home run every time that you’re at bat.” You just try your best and you make do with what you have. I’ve had people – friends of mine – who are like, “Oh, isn’t that a lot of pressure doing it every week?” And you know, because it is every week, I feel like it’s less pressure. I just can’t worry about fixing it forever. I have to get it out and get it done. You’re doing it every single day. You try your best, of course, but every one’s not going to be the best comic you’ve ever done.

It’s all about the rhythm too, right? The fact that you’re making comics on an ongoing basis is what means you can make the next comics after those. It’s a building process where even if you’re trying to make things that work on their own, there’s a cumulative effect, where even if they’re completely, I don’t know, self-contained in theory, they’re still all connected. You build. Is that making too much of an assumption?

No, you’re right. I belong to the National Cartoonists Society. Basically every year they have an awards thing, the Reuben awards. I’ve met a lot of cartoonists, and it’s great. It’s a great community. But I’ve heard this a lot. We all kind of agree that if you’re doing a daily strip or panel, you’re in your rhythm, and then like, then you go away on vacation for like, a week or two. You almost regret going away for vacation. Because when you come back, you’re cold. And getting started is the hardest part. The first time back, you feel like, “Oh, no, can I even do this anymore?” It’s a real struggle to get warmed up again, you know? You just feel like, maybe, a runner that took a year off from running or something.

Yeah. Keeping that routine going is key.

Yeah.

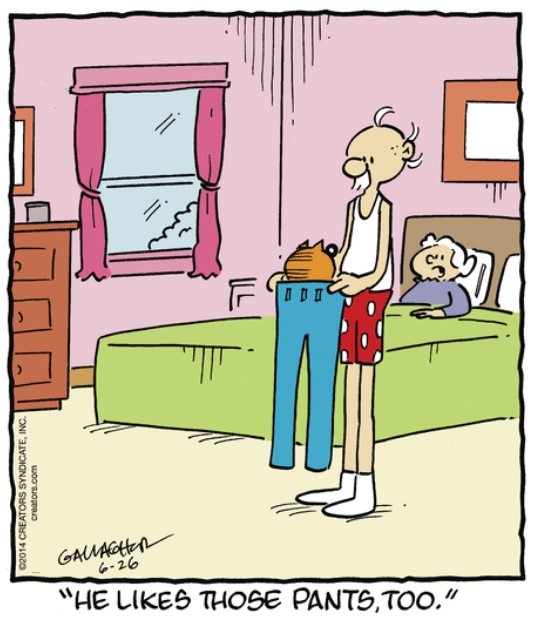

Listen, I wanted to ask about timing in your comics. It seems like even though you’re doing a single panel comic – or maybe even because you’re doing a single panel comic – there’s still a lot of thought about timing. You do this thing where you don’t show the middle of events. You don’t necessarily show the climax of what’s happening. You show either before it happens or after it happened.

Yeah. Right, right. I think that maybe that’s just kind of the humor that I really think is funny. Like something insane has happened, and the person’s calmly walking away from it. Another recurring thing. I do – it’s not a big theme, but it’s something I go back to – is Heathcliff is way up in the air about to pounce on somebody.

I know what you’re talking about.

There was one time I had two old men sitting on a bench and one of them goes, “We should probably stop calling each other ‘dog.’” It was when everyone was calling each other “dog.” Heathcliff was about to pounce on them.

Ha ha!

I would say your point is really interesting. The idea that it’s not in the middle of doing it. For example, I think a Sunday comic does show you what’s happening in the middle. It shows a beginning, middle, and end of something. But the daily, it’s more like one point in time. I had Heathcliff being chased by all these clowns. You know, they have torches and pitchforks. And they’re just like, “What’s he done this time?” You know, like, that type of thing.

Having to wonder or imagine what he did is funnier than actually showing it.

Yeah, it’s way funnier than anything I could come up with, probably.

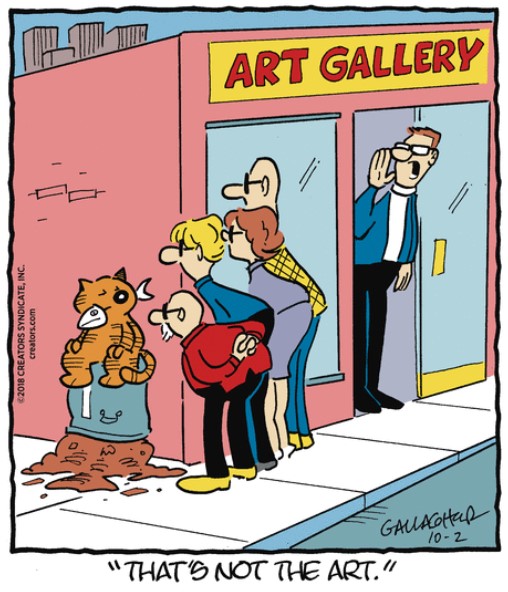

Another thing about the way you put it together is that generally, your caption is dialogue from an observer or someone who – maybe they’re involved, but they’re not the main character. It’s never Heathcliff saying what he did. It’s someone else, and it’s just very matter of fact. Matter of fact weirdness is always funnier to me than someone going, “Holy shit!”

Ha ha, right! I agree. That makes it funnier, in my opinion. This stuff’s going on, and, you know, it’s interesting. You talked about that with the observers. I mean, Heathcliff doesn’t speak, so it’s a challenge. That’s an extra challenge, but I like it. It’s something I welcome.

Right.

But I’ve had people online say, “Oh, here comes, I don’t know, another couple of guys in the background commenting,” and it’s like, well, yeah. I’ve done a few where I have had no caption, but not a lot of them. But what I mean is, I’m aware of that. I don’t want it to seem like it’s a formula, you know, and you try to write it in a way that it’s not the same thing all the time.

Repetition is an important part of art and humor, and repeating something can make it funnier or it can kill the surprise or just turn it into, like, a nostalgia thing. But there’s got to be some level of repetition even if there’s not an ongoing continuity or storyline or whatever.

Right. Like you say, in Heathcliff, there’s the helmets, or the robots, or the Garbage Ape, and all those things. And then in Peanuts, you have the football that Charlie Brown’s gonna kick or Snoopy is the World War One flying ace, and there’s the Great Pumpkin. Those are part of what makes it great.

Yeah, definitely.

I feel like every strip, every comic that I do can be read by somebody who’s coming in cold. I’m not doing an inside joke. There are things that repeat, but it’s important to me that people understand that every comic strip you see is just what it is. You know, there’s not like a hidden clue that you have to know to understand it. People think that it’s inside jokes, and they get annoyed by it, and I think that’s a legitimate thing to be annoyed by, because they feel like, “You’re leaving me out of this.”

So you’re very aware that every Heathcliff might be someone’s first Heathcliff, and that they might think you’re making it purposely hard to understand or, I don’t know, purposely obfuscating?

Right, of course, and I’m not doing that at all. I always feel like even if it’s hard to understand, if you give it a chance, and you read some more, you’ll understand what’s going on. But I never want to make it not understandable to somebody who came in and is reading their first Heathcliff comic.

We live in this world now where everything is explained to death on the internet, right? Where you can just look up “what does something mean” and either the creator or some expert or someone is just there to tell you what something means, and for some people without that, they can’t enjoy the art. Do you know what I’m talking about?

Yeah. Right. I do.

And you have people reading this comic in different ways. They might read it on an ongoing basis or they might have a particular comic pop-up because the internet decided it was weird or whatever, like “here’s this crazy thing that this maniac made! What could it possibly mean?”

Yeah, ha ha! You know, it’s funny…you know, there was a Heathcliff TV show in the 80s. There were a few of them. They were successful. They were hits, you know? There are people who remember that, who are older, like my age, and that’s how they know Heathcliff.

Right, of course.

But the thing that I love is young people. I just got an email from somebody – she was like 20 years old – she was saying how much she loves Heathcliff. One year, a few years ago, the Reuben awards were in Philadelphia, and they had this great event the day after the awards show. There’s this beautiful old library in Philadelphia, and they had all the cartoonists that wanted to set up booths, and we just drew comics for free for anybody who came in. I was there with all these great, great cartoonists next to me. At one point, this young woman who’s probably like college-age – late teens, early 20s – came up and she was talking to me. Occasionally I’ll do like a theme week, where it’s the same theme for the whole week. She goes, “I just want to tell you, when you did dirt week, my boyfriend called me. He’s like, ‘I can’t believe it! I think it’s on, I think it’s gonna be dirt week!’ He was so excited about it.”

Ha ha ha!

I loved hearing that. It was great!

That sounds like a great fan interaction.

I loved it, yeah. I think you’re right about people reading it online. The fact is, it is online and it is reaching so many people, which is so great. When I first started, you know, email was around. The internet wasn’t really around like it is now, but I would get emails or fan mail. But now you get a running commentary, a lot of comments on everything you do every day. I say to the students I teach, “It’s hard as an artist sometimes to get destroyed.” Your work, you know, people can really kill you with their comments, you know? I’m like, you just have to develop a little bit of a suit of armor about it, and not let it destroy you and just, you know, be like, “Okay, well, that was a good comment.” But you also do get a lot of positive stuff. And I love it. I love that I can get immediate feedback every day. It’s really such a great thing. When I started cartooning that was not a part of it. When you’re, say, a standup comedian, you know, the audience is part of what you do. That was never really a part of cartooning, but now it sort of is.

Right. With the newspaper you might have had people write letters to the editor about Heathcliff, but because of, I don’t know, I guess the distance involved, a lot of people wouldn’t take the time to do that. Now, it’s more immediate.

Yeah, exactly. There’s also the Facebook page and Instagram page, so there are different ways for people to contact you. I don’t interact as much as other people, but sometimes people ask you things, and you write back to them, and it’s really great.

There are two sides to that, right? You don’t want to get to where you’re just out there defending your comic online against people who don’t like it or don’t get it. I’m always embarrassed when I see something like that happening. You have to be willing to let your stuff go out into the world without you at some point, right?

Yeah. Exactly. Like, I’m not comparing cartooning to fine art, but you don’t go to an art museum and the artist is standing there next to the painting and he argues with you if you say something. No, you let the art stand for itself, and they can hate it or love it, but it’s just, you know, you put it out there.

Yeah. I got an art degree, a painting and printmaking degree, and one reason I didn’t personally go to grad school is because it seemed like talking about your art was more important than making your art. I really just hated artists’ statements because it seemed like they were doing the work the art should have done. I hated seeing any words on the wall in a museum, but then I went to a Norman Rockwell exhibition –

Oh, wow.

– and there was historical context there on the wall next to the art. Like, it talked about how he was only allowed to depict Black people as servants at the Saturday Evening Post.

Wow.

And then to go from that to the one with the little girl, uh, Ruby Bridges, walking to school [The Problem We All Live With] and to talk about how part of that was a result of what he was allowed to do… because of that, I understood the art a lot more. So that changed my thinking on words about art to some extent, but I’m still dubious about the artist using their statement to try to make the art say something it doesn’t already. Does that make sense?

Yeah, yeah.

You know, a lot of people who are new at comics – I don’t know if you’ve seen this – will post all this stuff online about the characters and the background to where there’s more background stuff than there is comic, and maybe that’s the extreme, but to me, that is where over-explaining or defending your art online kind of leads… to where the art is like, less important than the discussion.

Yeah. I think The Far Side is great. There are so many comic strips or panels that just were born from The Far Side. And The Far Side was so unique. The guy, everything he did was hilarious. Even his style. I remember getting this book when it came out. I don’t know if you ever saw it. The Prehistory of The Far Side.

Oh, that’s one of my favorite books.

One thing I loved in it, is seeing that he could draw way better than he did in The Far Side. He did that type of drawing on purpose. And it fit the humor exactly, which is really something. You talk about commentary, I think there was some stuff where he talked about his comics. And you know, I didn’t want to hear from him about it. You kind of want to, but I felt like he should just be up in this laboratory creating this stuff. I don’t want to know too much about him, what he thinks about it.

Yeah, exactly. But that’s something that came out before the internet age that we’re in now, so it was, like, a rare look into what he thought that wasn’t just available online. And it was him saying stuff as it came out. He was saying it later, after the fact.

Yeah. Right.

So I guess there’s a thin line between when someone is over-explaining or if they’re giving important context. Who am I to say when it’s alright and when it’s not?

Yeah. And it’s like, as I’m saying this about not wanting to know, I’m also dying to know this.

Ha ha!

I want to hear from this guy. And it’s just because he is somebody who really has stayed out of the public eye even though he’s such a huge figure. Same with Bill Watterson. Calvin and Hobbes. There’s a documentary about it. He just avoided talking to anybody and never did any licensing of his products. He only did the books, the book collections, you know?

He definitely took the thing about not talking about his art seriously. Maybe to an extreme.

Right? I mean, I’ll put things out on social media. And sometimes if somebody asks a specific question, I’ll respond. But for the most part, I feel like I’d rather have the people say their piece, and they can have a discussion. If they hate today’s comic or if they love today’s comic, they can still see what I did tomorrow, and maybe that will be different.

You don’t want to explain what the comic means, though.

I’ve always felt this way. If you like a certain painting and you’re like, “Oh, here’s why I like it,” but the artist comes out and says, “No, it’s not that at all,” that’s telling them what they’re supposed to think. Again, I’m not saying that the daily comic strip is fine art. But if somebody sees something about it that they really like, and I had no idea that that was what they were gonna like about it, and I say “that’s not what it is,” I just ruined it for them by opening up my big mouth. Just let it sit and let them enjoy. That’s kind of the nature of any type of any of the arts, you know?

The reader has to bring something to it.

Yes! Yeah, right. I think with music, for example, you love a song for a certain reason. And you don’t want the artist coming in and telling you, “No, you can’t like it for that reason, you have to like it for this reason.”

Absolutely. You know, you’ve done a lot of Heathcliff comics at this point, and as near as I can tell, there aren’t any book collections out there. Are you content with it existing just as a newspaper and internet strip, or would you like to get some books out there?

I’m hopefully going to get something together. I’ve been talking to people about getting book collections of stuff that I’ve done in recent years. And I’ve put together something just to hand out to people when there’s some kind of like, business thing or something, or given it to friends of mine, and they’ve really liked it a lot. I’ve talked to a couple of people, and, hopefully, in the near future, there will be some collections of the Heathcliffs that I’ve been doing. There are so many of them, you know, the 70s and 80s books.

After I wrote that essay about your comics, some people I know messaged me like, “I want to get this guy’s books. Where are they?” I think especially now the way some of your comics blow up on the internet there’s a market for it in a way that there might not have been in the past, beyond people like me who are just obsessive about comics.

Great. Thank you for saying that. I definitely want to do that. You know, I’ll tell you, I just really enjoyed your articles, yours and everyone else’s, from Heathcliff Week. You know, you’re joking around saying that you’re obsessed about it, but that’s what I do. I obsess about it because I’m doing it as my job. And really, it’s a great feeling to have somebody kind of thinking along with you. And the stuff you said, I was so happy reading it.

As much as we’ve talked today about how important it is not to interfere with the art and to let people interpret it, it’s also really important sometimes to know that someone is receiving you, that you’re on the same frequency. That’s always a good feeling. Those two things are maybe a contradiction, but they’re both true in my experience.

Yeah, right. You’re mostly alone when you do comics, and connecting like that is great.

Just to switch up, I have seen from a couple of other articles out there about Heathcliff that you draw other stuff. Is any of that out there and easily available? Are you working on other stuff simultaneously and putting it out, and I’m just missing it?

I’m not doing that. I do my own stuff, and I really should maybe start putting it out there. I have tons of notebooks of just my own. Just stupid things that I’ve drawn, or things that I think are funny, maybe kind of weird, but just my own thing. And I would say it’s in my own style, which is a little bit different than the Heathcliff style. A lot of times, if I’m done with work for the week, I’ll work on that stuff. I have my main office in my house. It’s on the second floor. But in the basement, there’s like this dungeon.

Ha! You switch to the dungeon to draw something other than Heathcliff!

Yeah, yeah. I have this room where I have another drawing table. And I like going down there. I like to come up with ideas and just sit down at the end of the week, maybe look at what I did. And then I like to just take a little bit of time and draw my own stuff. It’s a nice release, you know, not having to do this thing that’s very regimented as much as Heathcliff is. I just kind of do some stuff freely. I do really think about getting my own stuff out there a little bit more

Even though you like the freedom there, it doesn’t sound like you resent working on Heathcliff.

No.

The idea I get from talking to you is that you really enjoy Heathcliff.

Yeah, yeah. I have to say, when it comes to it, I love being able to draw Heathcliff. I’m telling you, I’m so thankful. If I have to imitate a style, I love the style of Heathcliff. I love coming up with jokes, it’s like my favorite thing, to be able to sit down and come up with ideas and do comic strips. Heathcliff is a great character… Yeah, I’m very thankful. I love it.

How many people get to have a job they love so much?

I know. I know! And like you said, I’m not resentful of it. But it is just one way to draw, and it’s something I’m doing all the time. So sometimes I like to change from that and do something different. I even got an iPad, and I’m doing more digital stuff on Procreate. I’m learning that a little bit more. It’s amazing, all the students that I teach, they work completely digitally. I’m amazed when I see the work that they do. I’m, you know, still getting my feet wet, trying to do that kind of stuff a little bit more, but I’m still a traditional cartoonist. I love the feeling of a pen or pencil on paper. That’s my thing. I love that.

That sounds like a good place to wrap this thing up. I’ve loved talking to you, Peter. This was great.

Same here, Andrew. Glad to speak to you. Bye-bye.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply