At his core, Liam Cobb has a fairly uniform style of linework; his people—the driving force of his stories, ever at odds with their surroundings—always bear an elegant blankness to them, an aversion to overt articulation, allowing them to melt into their successors in the book; the environments, meanwhile, are unwaveringly, alienatingly precise. Yet he is also acutely aware of his fixed underpinnings as an artist. In fact he uses color and texture to mask these constraints, and to great effect—leafing through What Awaits Them, the latest1 (and largest to date) collection of short stories by the accomplished cartoonist published by London’s Breakdown Press, one might be forgiven for assuming it’s an anthology with multiple participants; at a total of 200 pages, its six short-form pieces sport a striking variety of textural styles, settings, and tones, displaying an artist for whom a resistance against self becomes a driving force.

Under Cobb’s hands, the stylistic-aesthetic component becomes dialectical as well. What ties the collection together is a staple in his work, a sociopolitical chronology that runs, one might say, from Joseph Conrad to J.G. Ballard: that is, between an immediate and long-term misery of decadence and decay (I think here of Tommi Musturi’s one-man-anthology series Future, though Musturi has a greater tendency to lose himself within his stylistic play, often at the detriment of his messaging). As the cartoonist goes back and forth in time, one can see Cobb’s ascription of style to period: his fin de siècle trio, “Green Graves,” “Slow Drift,” and “Two Men in the Jungle,” are decidedly grimier and more tactile, as their narratives bears more of a physical impact; “The Fever Closing,” “Adapting Walls,” and “The Inspector,” however, tilt heavily toward a modern sleekness, their lines sporting a mostly-uniform weight and precision, their colors fuzzy and cotton-candy pale. Their decay, while just as visceral, has its sheen of newness: new skin pulled taut over an old corpse.

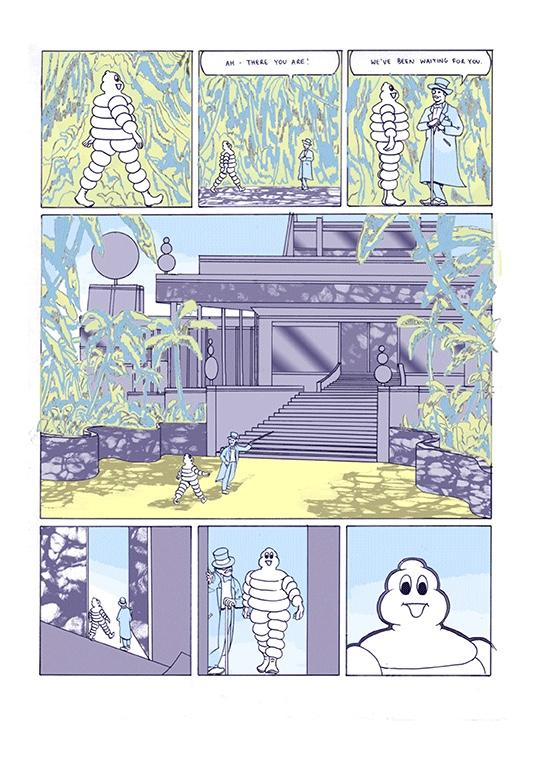

The opening story, “The Fever Closing” (2016), sees a man arriving at a lavish party on a jungle island; upon arriving, he dons his costume, taking on the appearance of the Michelin Man. Yet, as we have already come to learn from other media about this sort of gathering—I doubt any of us here are obnoxiously rich enough to attend one, but if I am mistaken about you, dear reader, I am more than happy to pass along my PayPal—they hardly ever feel like a celebration. And, indeed, our Michelin Man soon finds out that hardly anyone is really wearing a costume—he is the guest of honor, chosen to be the party’s violent, miserable sacrifice. Here Cobb greatly benefits from the brevity of his story—at less than twenty pages, everything moves quickly, too quickly; his figures are less characters than caricatures, all archetype and stereotype. Artistically, too, everything is drawn all too smoothly, with Ikea-blank characters and unrendered surfaces, their only texture being a light-colored staticky fuzz; the only thing that is rendered is the island’s flora, an unruly mass of overwrought texture, to tell you everything you need to know about the man-made elements: they are not, in any real way, alive. Even the story’s title is less a title than a thesis statement; there is a feeling, more than anything, of a lack of control, of a situation that couldn’t ever result in anything good. Sometimes the light at the end of the all-too-narrow tunnel is just an eighteen-wheeler coming your way.

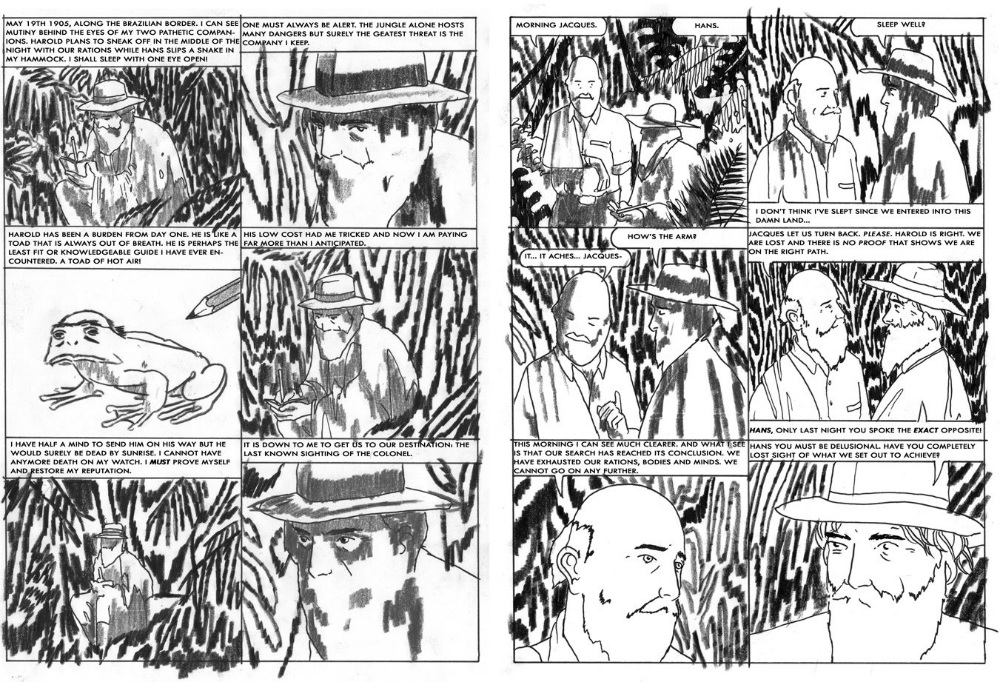

Alliances, in Cobb’s stories, are ephemeral things, formed out of reluctant necessity; they are permanently bursting at the seams, ready to buckle. “Green Graves” (2016) follows a trio of lost jungle explorers whose leader’s refusal to account for anything other than the glory of success—a prospect increasingly out of reach—leads the only way it ever could. We are not given any indication, at any moment, that success was ever an option, not for these men: the leader’s incompetence is equal only to his hubris, and his failure to recognize his companions as his peers. Yet, at every turn of their road, Cobb is eager to remind us that, in spite of their disparity in power, they are all equal in one way, the only way that matters—their deaths are just as pointless.

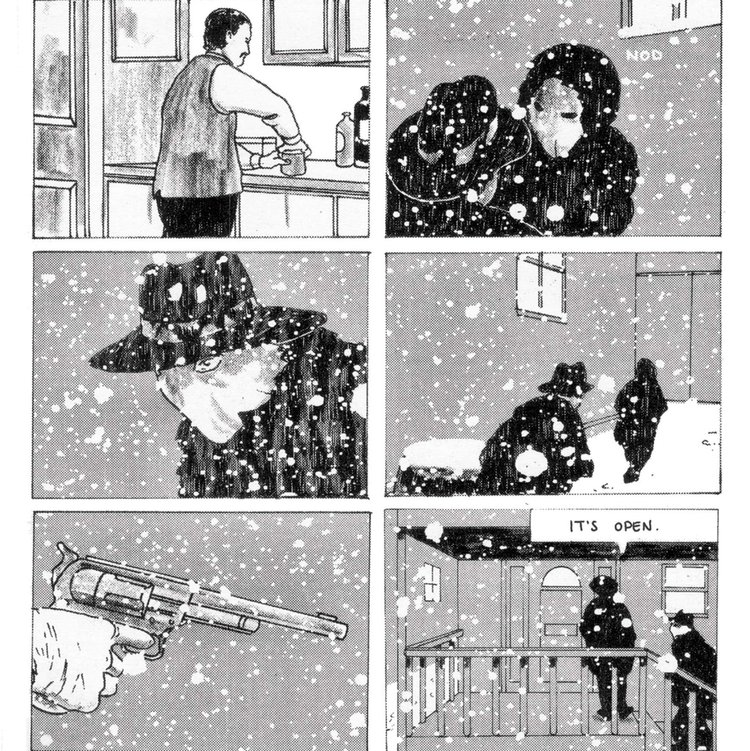

The same air of social dissonance carries over to “Slow Drift” (2017), Cobb’s stab at a western narrative, and maybe the most straightforward of the six stories. From the beginning, its two vagabond outlaws are a profound mismatch; the unnamed older one of the two is at peace with his slowness, with his meagerness, while the younger one, Dunleavy, is rushing to get things over with before they have even started.

As far as artistic approaches go, the story appears to side with the older man; it’s a sparing, almost oppressively rhythmic affair, rarely diverging from its six-panel grid. There are two moments in “Slow Drift” where the austerity of Cobb’s cartooning shines; at two different points, the cartoonist breaks away from the two characters for twelve panels of trees in the snow. The combination of the flatness in his art and the intensity of his mark-making makes the trees look almost abstract in their simplicity, somewhere between Craghead and Breccia, their forms not rooted so much as engraved into the view. In another spread, Cobb draws his two characters on horseback in the snowy expanse, as one moves faster than the other; yet, instead of opting for a Muybridge riff, there is an oppressive stillness to it, as if they are moved instead of moving of their own volition.

Early on in the story, the two characters break into a man’s house, and the cartoonist depicts his killing with a striking detachment: we only see the house from outside, in a sequence of twelve mostly-unchanging panels, its doors and windows shut. All we get is the report of a gun, presumably Dunleavy’s firing far too many times. By now, the fourth story in the collection, the rules of Liam Cobb’s work should already be clear, and here the cosmic weight of inevitability that anchors his stories metastasizes into something infinitely more brutal, more intentful: retribution. When Dunleavy kills his partner’s aging horse, his partner finally snaps and kills the young man. We see this killing, and we see what follows: again, too many shots fired. Dunleavy’s rush, of course, was futile: in Cobb’s work, the only direction you can rush in is down.

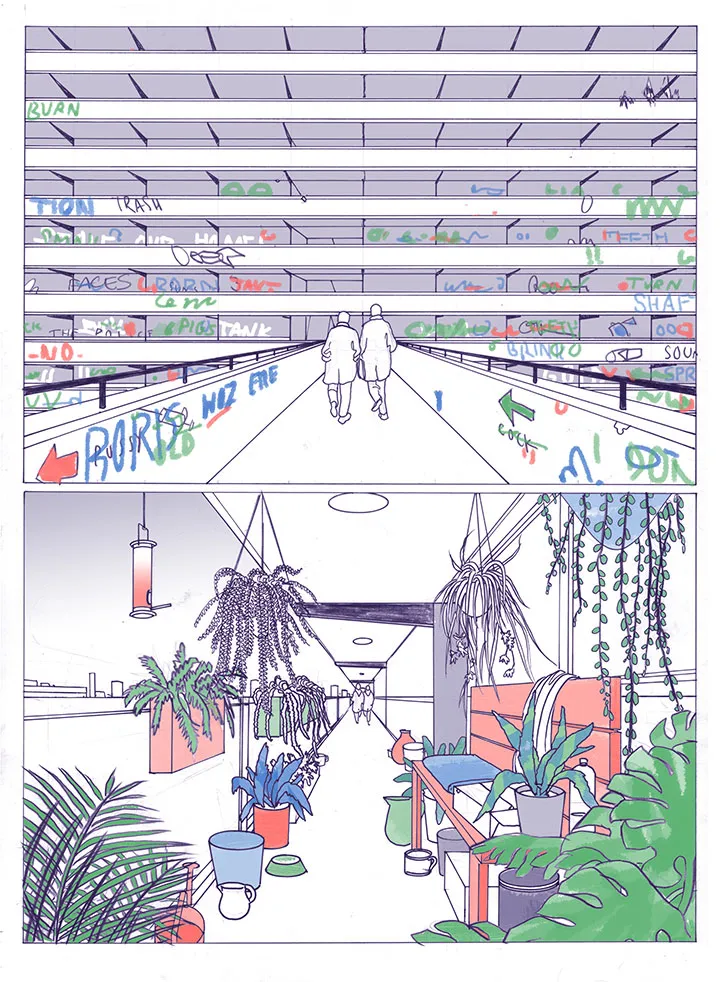

“Adapting Walls” (2017) is the sole piece in the book to take place in a modern urban environment, though the apartment complex at its heart, based on London’s demolished Heygate Estate, is about as unruly as the author’s jungle landscapes. As the story’s estate awaits its demolition, it becomes feral. Plants accumulate, watered but untamed; rats swarm through its halls, escaping floods. The apartment complex itself is unmoored; in recurring external shots, it is surrounded first by city, then by water, then by jungle, then, finally, as it is demolished, by desert. The cityscapes are reminiscent of the urban vistas of the final movement in Vaughn-James’ The Cage, dilapidated and worn yet not quite alive, while the deserts distinctly call to mind the cartoonist Lando, so archetypally blank and vast that to compare it to Ozymandias would be so obvious as to reveal the narrowness of a critic’s vocabulary. Taken as a whole, the story is a howl of despair; there was life in those halls, first abandoned and neglected, then, when the neglect reached a certain level, promptly discarded. Yet the building still stands amidst the dunes—a reminder, or a scar, if there is even a difference at all.

There are, in spite of it all, some moments of respite. “Two Men in the Jungle” (2017), the shortest piece in the book, revolves around an English scientist studying fungi in South America, who finds himself attracted to his assistant, Juan, in spite of the language barrier between the two. Tyler Landry’s cartooning comes to mind here, especially the restraint in Landry’s mark-making; Cobb’s characters are drawn, as they often are, in broad strokes, yet you can tell exactly what they are supposed to look like. It is not blank so much as purposeful and economic. Noteworthy, too, is the contrast in Cobb’s coloring, which here takes on a shade of Joe Kessler; there’s a four-panel sequence that shows the two men in their tent, almost as though in night vision, their contours drawn in orange lines of unvarying weight onto a deep blue. As the two characters eat a hallucinogenic fruit and transform in one another’s eyes into lumpy sprites of hair—part of me wonders if a visual cue was taken from the gag in the Tintin album Explorers on the Moon, wherein policemen Thomson and Thompson accidentally take pills that gives them similarly unruly tresses—they are freed from their duties as humans, wandering the jungle and melting into one another, and here too the vibrant, searing coloring also has more of a bit of Kessler’s Windowpane in it.

There are two ways to read this story, either as satire or as straightforward effort: in the former, Cobb mocks Conrad’s well-criticized tendency to critique colonialism while failing to view its victims as entirely human; in the latter, Cobb merely falls for the same trapping. The exotic has an appeal that precludes one from viewing it through any other prism; the scientist here passively refuses to enhance his communication with Juan, continuing to shower him with the rapid-fire English to which the latter can only respond with the kindly-laconic “Sí, señor.” Cobb himself describes the story as one with a happy end, though one wonders how happy it may be—in finding their feral common ground, the two men in the jungle appear to lose everything that makes up their identity. Theirs is not a love borne of intimate knowledge, but of a gaping, sucking absence.

There is, I think, a case to be made for What Awaits Them as something of a declaration of aesthetic intent for Breakdown Press as a whole, however inadvertent—the variations in Cobb’s cartooning serve as a point of convergence for several other prominent voices in the Breakdown milieu, between whom one might not necessarily think to make an immediate comparison. The textural haze effect in “Green Graves” and “Adapting Walls” is distinctly reminiscent of Conor Stechschulte; the latter story’s decidedly austere, clean-to-the-point-of-wrongness geometry, contrasted with the desert landscapes, bring Lando to mind; the simplification of shape, contour, and contour in “Two Men in the Jungle” is easily comparable to Joe Kessler—this collection is not just demonstrative of the artist’s stylistic range, but also a striking dialogue between artist and platform. I can’t possibly assert as a certainty that these comparisons are intended by Cobb himself, but even as just a product of sheer artistic instinct we have a creator in command not just of his isolated voice but of his aesthetic context and surroundings as well, and Breakdown does well to emphasize it.

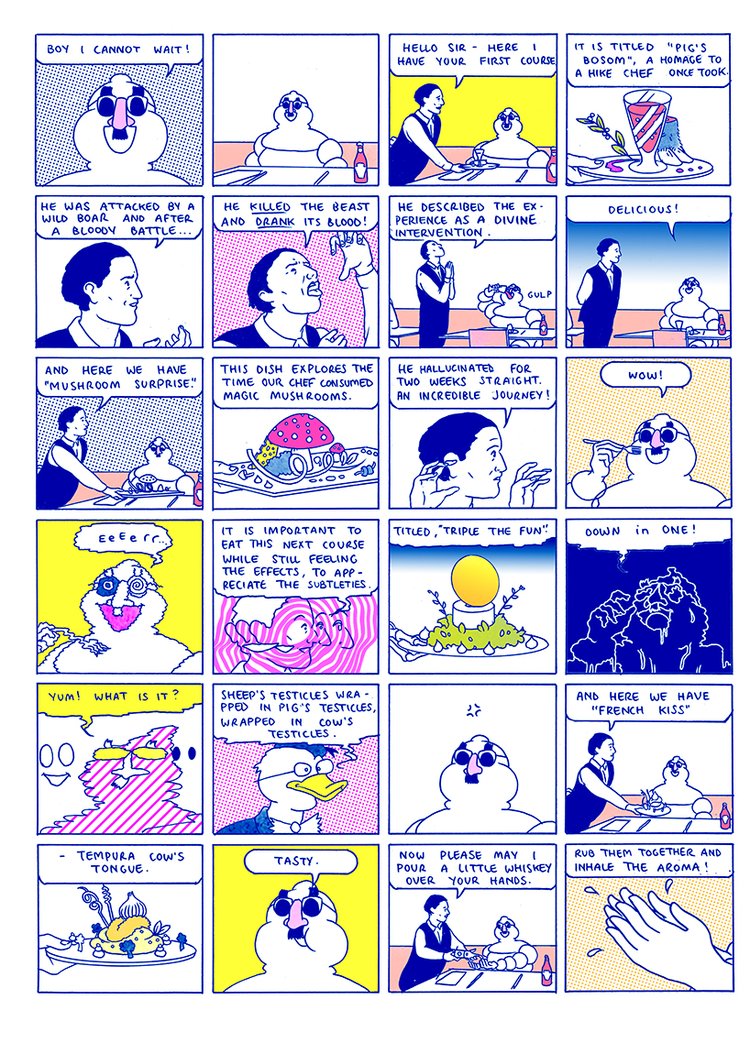

When the end rolls around, it bears a familiar face: “The Inspector” (2018) sees Cobb return to his vision of the Michelin Man, this time not as a costume but as its own persona. As he plops his all-too-lively protagonist into a Kitchen Confidential/Diners, Drive-Ins, and Dives pastiche, we get to see the cartoonist stretch his comedic muscles, an aspect largely absent from—or at least not as overt in—the rest of the collection. He chooses an easy target, being the dissonance between the rarefied airs of the Michelin star and the ‘earthly’ vocation of the tire (‘tyre,’ if you’re British, in which case, my condolences) company that awards it, but he carries it remarkably well by underscoring the contrast. Our Inspector, the story tells us from the very beginning, is completely lacking in any real awareness—he turns around to face the reader as he drives, hitting and killing a deer then driving away unbothered: he is an inspector in name only, incapable of discernment of detail. From this point, the punchline is almost obvious: he goes through a succession of restaurants whose pomposity would make them an obvious candidate for the prestigious award, only to ask for the supposed simple pleasures of steak and ketchup. The incompatibility is absolute, past the point of bridging.

This would be almost tired if not for Cobb’s assuredness of craft. He offers some striking rapid-fire cartooning, fitting several pages with no less than twenty-four panels apiece while sacrificing none of the detail, first as one restaurant presents our inspector with a tasting menu of increasingly ludicrous dishes (and their lysergic impact) then as he finally raises the ire of the pretentious, violent chef. But the inspector, of course, gets the last laugh, as he awards three Michelin stars unto a largely-unremarkable taco place, because finally there was an establishment that could give him what he wanted.

After a delightful fight sequence against several other capitalist mascots (the Pillsbury Doughboy, the Kool Aid Man), we cut to a beachside finale. The Inspector sits by the ocean with a beautiful girl who fawns over him, and winks at the reader as the sun sets—the sun bearing the Michelin Man’s own visage. It’s the restauranteurs that get the brunt of Cobb’s contempt, but their ‘opponent,’ he reminds us, is no hero—just as the chefs are consumed by self-importance, the Inspector is completely immune to art; his (and his employers’) warping of discursive gravity is a net negative for all of us. Perhaps the epitome of Liam Cobb’s vision: all the aesthetic makings of a happy ending, and none of the happiness.

What Awaits Them, then, marvelously delivers on its promise: it’s a nonstop hurtling, an ever-tightening run with no relief in sight, an aesthetic panoply of total exertion. At the absurdity you can laugh, and at the sheer discomfort you can wheeze. In Liam Cobb’s world, the two are one and the same—a desperate rasping sound, and at the end you’re helpless and out of air.

- Curiously, Breakdown advertises this book as the first collection of shorts by Cobb, though it is predated by the publisher’s own riso-printed Conditioner, which collected three shorts in a smaller format, itself succeeding Cobb’s self-published Shampoo. One of stories in Conditioner, “Adapting Walls,” appears in What Awaits Them, though the other two are excluded. ↩︎

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply