Tummy Bugs, published by Breakdown Press, is the first volume in a series of what Leomi Sadler has declared The Leomi Library. Collected within are a dazzling array of comics, drawings, and paintings spanning 2009 to 2020, finally introducing Sadler’s work to a larger audience. A lucky few have seen some of these pieces before in publications like CF’s stellar (and criminally limited) mini-anthology Off the Press from 2012 or the long-running Kramers Ergot and Decadence anthologies. More limited still are those published by Sadler and her brother Stef’s Famicon Express, a cult publisher in the best sense of the word, who, alongside themselves, have also published like-minded outsider individualists like Jonathan Chandler, Kitty Clark, Yannick Val Gesto, and GHXKY2.

Despite its lengthy timeline and wide range of material, Tummy Bugs is incredibly cohesive, feeling less like an odds-n-ends collection and much more like the gathered work’s ultimate form. This is a testament to Sadler’s ability to deftly stitch together seemingly chaotic elements into a whole much greater than its parts.

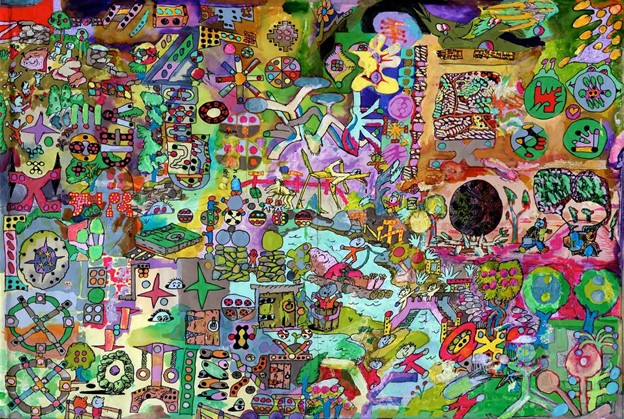

Sadler’s world is one of tension and contradictions, a world of play and pain where the line between tire swing and stockade is wobbly and smeared. This world is populated with a wide range of characters: frequently humanoid creatures, bugs of all sorts, anthropomorphic machines and vehicles, or faces grown out from symbols and shapes that otherwise decorate the world. Scenes are often bustling with activity and frequently cramped for space. There is a feeling reminiscent of Richard Scarry’s Busytown, everyone busy with a job to do, but here under the cloud of capitalist realism. Is there enough space for anyone to really live comfortably? Are they being paid a living wage? Do they have purpose outside of their work? The line between person and machine is blurred, the Transformer, the Gundam, the Amazon warehouse employee. Frequently the characters speak of loneliness and boredom.

This isn’t to say that Sadler’s world is bleak and dystopian. Quite the contrary, the pages here are always playful, full of color both beautiful and gaudy, flowers and fauna sprouting widely. Almost everything in Sadler’s world wears a smile — though most with a mischievous tilt. It’s complex, not so easily written of as a depiction of fantasy or hell, but eerily reminiscent of modern life.

Sadler’s paintings slip between the comics. In a few, so many things are layered that it feels as though stickers have been placed over our field of vision, or a videogame HUD is trying to show us how much stamina we have left before we pass out. A neon square peeling back on the corner of the sky advertises a sale price, a lopsided star decal from a coin-op vending machine is stuck on the page. There is the chaos of a child’s toy box mixing with the plastic bins of Happy Meal toys at a flea market. Sadler has spoken about being drawn to “stuff that’s gone slightly wrong, like on crisp packet packaging for cheapo brands or funny signs for shops.”

In a recent video, Sadler pointed to a small collection of Thomas the Tank Engine toys as a source of inspiration. Their soft, round faces growing out of transportation machinery make for a natural fit and it’s hard not to recall the episode (The Sad Story of Henry) where a train named Henry is afraid to leave a tunnel because of rain so the Fat Controller turns the tunnel into a prison cell, bricking Henry into solitary confinement for his refusal to move and confront the rain. In the press release for a 2018 exhibition, Sadler speaks about Thomas’s world and its hierarchy, which she finds appealing. “What does it feel to be chained to the backside of Edward and dragged back and forth with no independent engine? It’s melancholic but they also seem to have such glee in their misbehavior.” You can’t play in an industrialized world without getting a bit dirty, pain and pleasure blur together as simply as the living and the mechanical.

Sadler’s world is certainly not without plant life, strange gangly trees that reach up and around, branches that end in bulbous shapes like Mickey Mouse’s shoes. Despite schooling in graphic design, Sadler’s work is decidedly not full of clean lines and slick curves but rather the organic gloopiness of mud and the drip of too-thick paint, the uncontrollable. Sadler’s graphic design background comes out through mechanical diagrams, the layout of instruction manuals, the methodology of simplified technical training. One could draw a line from one of Sadler’s characters that passes through homemade stuffed animals but ends in a car manual.

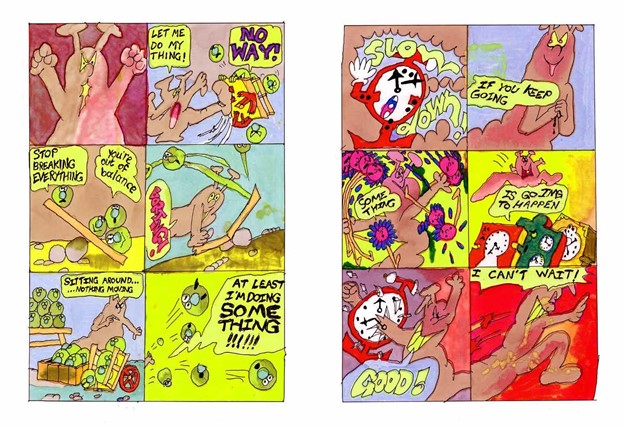

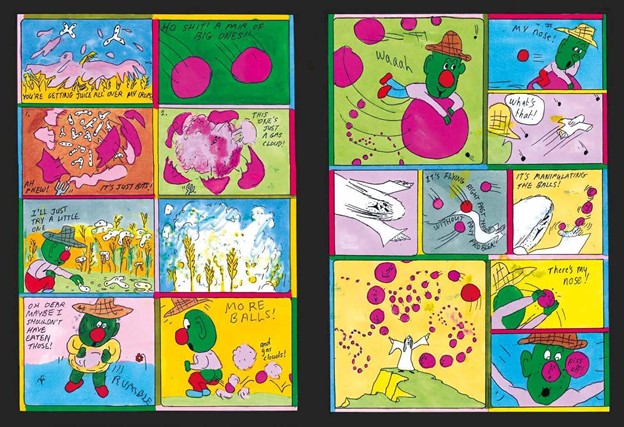

In comparison, the comics that populate Tummy Bugs are often quick bursts as opposed to the frequent layering accumulation of the paintings. The lines in the comics are sharp and quick, everything looks on the verge of eruption, falling somewhere between a messy amateur manga strip and Gary Panter’s Screamers logo. The punchlines are reminiscent of gags quickly scratched into a school desk while the teacher’s back is turned or penned on a scrap of paper while the boss is out. Their subversive quality comes not entirely from their content but also from the associations the style and context bring – a textbook that tells you to turn to page 43 only to find “you’re a wanker” or an excessively veiny penis scrawled on the page. The characters often interact with each other and the world around them through trickery of one form or another.

Frequently the text in the comics takes the form of a character’s internal monologue, offering themselves words of comfort or encouragement as they make their way through the world, encountering bugs and slugs speaking in Zen koans or giving advice on the road ahead, gnomes with big red noses and funny caps, something like the Smurfs mixed up in a stoned game of D&D. In one strip a mass of bugs provides peace by consuming those in need, quite literally begging to be devoured.

Some will surely be baffled by this book — its unwillingness to avoid the messy or the abject, its garishness and unbridled energy too difficult to grab hold of — but for those willing to be taken away, they’ll surely find the work endlessly fascinating and absolutely unlike anyone else making comics today. This book isn’t just an introduction to Leomi Sadler, it’s a defining statement of sorts, even for those familiar with her work over the years. Never has there been such a deep and dense collection of her work in one place. It’s stunning to see it all together, beautifully bound, old black and white strips now bursting with color, zines that disappeared in a blink finally readable, the old work communicating with the new across pages. Here’s hoping that this is only the first volume of many more to come.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply