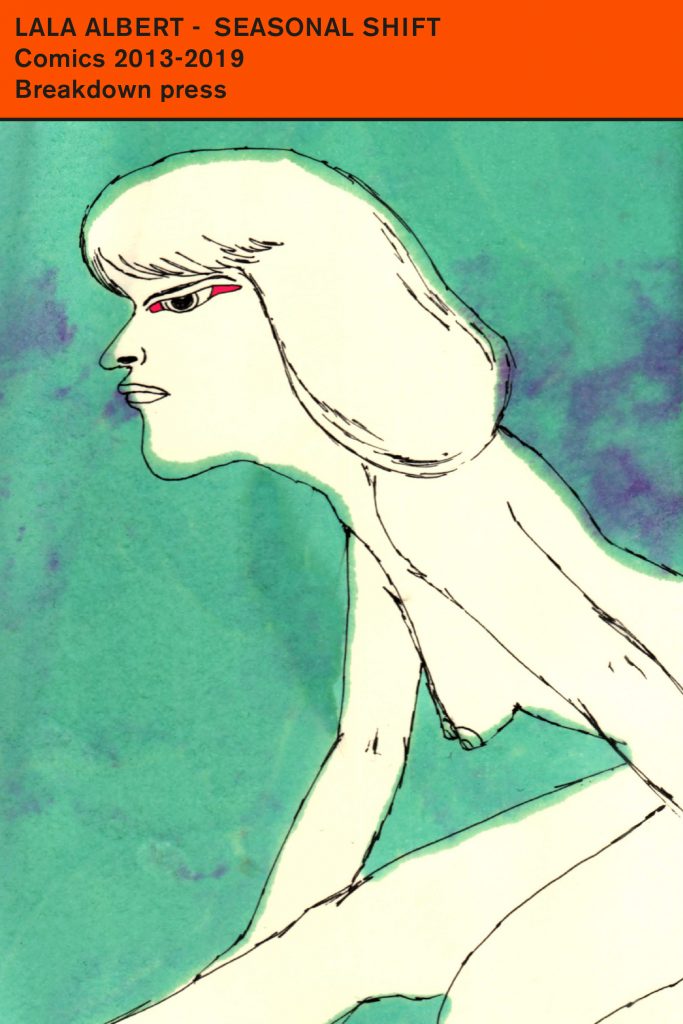

Right from the start, I was prepared to love Seasonal Shift, a collection of Lala Albert’s works from 2013-2019. Like Albert, I despair about how our impact on the world is exacting ever new unfolding dangers. I, too, fear the aimless ways that 9-5 jobs transform our thinking. I, too, try to dwell among non-human beings, wishing to observe and love them in a way they’ll register as sincere. So, yes, I am raving here, madly as well as throwing my hands up in great acclaim after reading Albert’s collection.

In spite of the prevailing hopelessness present throughout Seasonal Shift’s stories, their mostly nameless characters reach out fingers, tongues, and wings towards momentary grounding. This book is an exploration of the falsity that separates individuals’ lived experiences and the, often misdirected, attempts of those trying to exists beyond those separations through forming bonds with other beings. The results are often horrific, but never nihilistic as Albert refrains from judging the characters’ responses to the world as they live in it. Call these comics’ affective experiments noble, silly, or horrific; Albert renders all tones sublimely.

Seasonal Shift comprises ten comics of varying lengths plus an introductory interview with Michael DeForge and a handful of sketches spread throughout the collection. In the interview, DeForge states he doesn’t see Albert’s comics as body horror due to their often emancipatory results. However, I believe that the horror element is intact and intentional on Albert’s part, the horror existing not in the changes from one state of being to another, but from the characters’ and reader’s shared disillusion that the state prior to transformation had any true permanence.

This is most apparent in Seasonal Shift in the pieces “Starlight Local” and “Brainbuzz”, comics that are sensual while developing a foreboding sense of the eventual transformations to occur. In “Starlight”, the two humanoid leads meet on an interstellar commuter vessel, deciding to pass their travel time with screen watching, sex, and meals from the food cart. Initially, the story operates as a sci-fi romance without any evident tension between the characters. This remains until one invites the other to a previously unexplored form of intimacy, leading to a change in physiology and sex play that ends the burgeoning relationship. Once the reader arrives at the story’s end, the aesthetic choice of one character’s anatomy is no longer a visual detail from the characters’ first sexual encounter, but the instance where horror is foreshadowed.

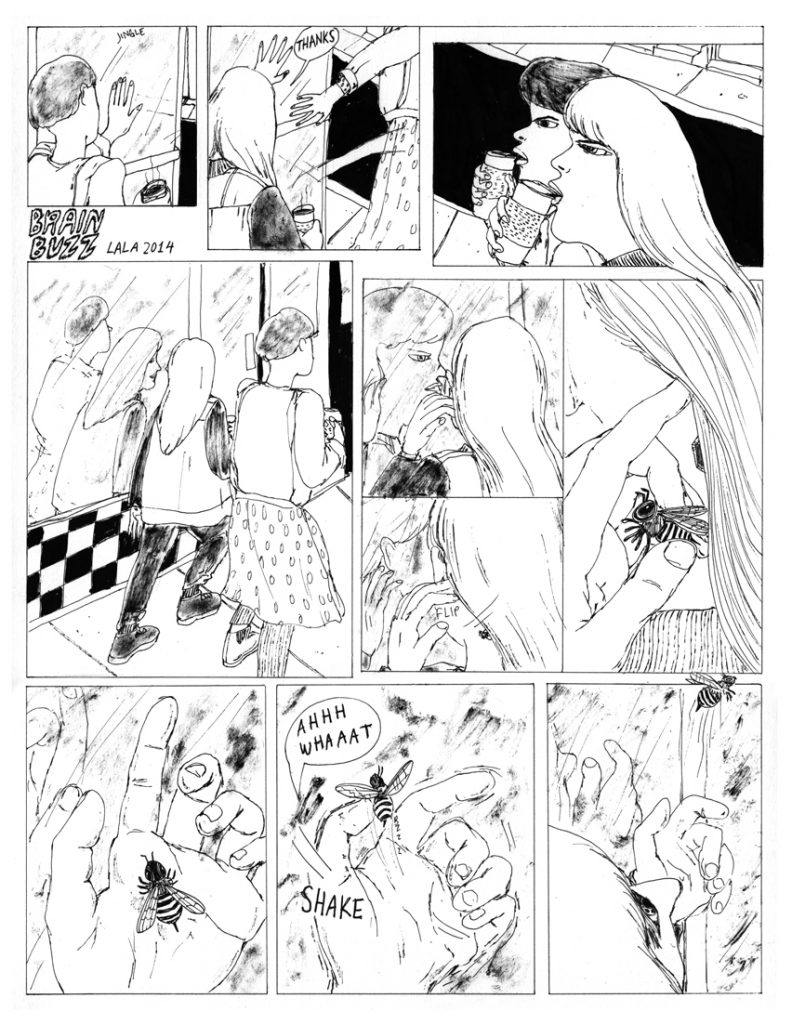

“Brainbuzz” focuses on a woman attempting to quell an internal buzzing that initially presents as bees in her hair and a sensation akin to a migraine. She leaves work, masturbates at home, then invites a crush over as the buzzing continues despite her efforts, their sex triggering an internal vision that results in the emission of a honey-like cum that coats her and her crush. “Brainbuzz”’s main character seeks an escape from monotony, depicted in her urgency to leave her job as the clock hits five and in the furious urgency with which she conducts every act. As the ejaculation of honey ends, a smaller version of the woman emerges from the side of her head and leaves the scene, now free of its larger counterpart.

“Starlight Local”’s characters aimlessly travel the galaxy and “Brainbuzz”’s lead gets caught up in a flurry of monotony that has her screaming at pigeons to get out of the way. The relationships nurtured through the characters’ sexual encounters are not capable of addressing these characters’ social alienation and bodily disassociation, respectively. Characters’ transformations are not played as punchlines or jump scares, but the inevitable result of not directly attending to the emotional crises within their bodies. As “Starlight Local” subverts the sci-fi trope of fun interspecies sex to traumatic ends, “Brainbuzz” disintegrates the border between the mind’s distress and the material body holding that frustration. Their endings don’t illustrate metaphorical outcomes about the characters’ interiority but rather demonstrates revaluations of that world’s physical reality by the characters, and the reader by extension. These stories rupture their existing reality, and readers are meant to understand that its characters come to exists in the world differently ( one as a sexual assault survivor and the other as an emancipated inner self).

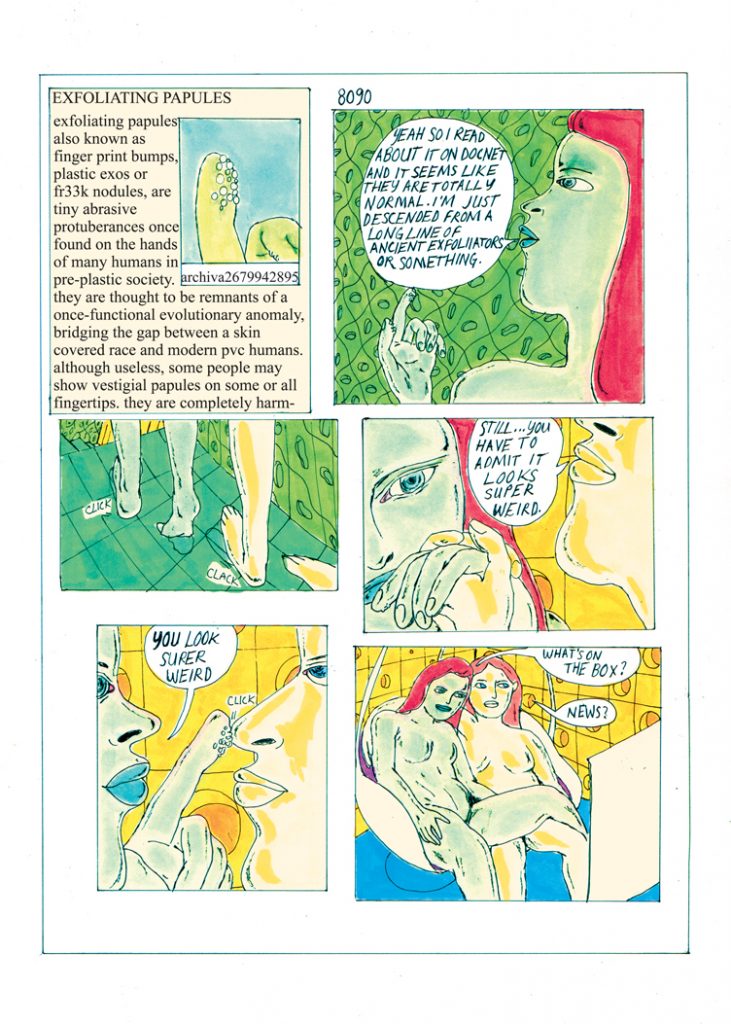

Albert’s collection also drew me in with its renderings of environments, using interior design to ground high-concept speculative narratives and deepening the stories’ undercurrent of dread. This impact of Albert’s design choices on tone management is best illustrated in “Future Shock”, a story where Albert imagines how microplastics might generate new evolutions in human life.

This story explores how this evolution, catalyzed by anthropogenic activity, impacts humans’ physical interactions by altering human physiology and proposes that, even amid those changes, humans are going to want to and chill. Leaping across several millennia, “Future Shock” uses a combination of news reports, doctors’ visits, and interactions among lovers to depict how even the most horrific changes can become mundane. Physiologically, these changes first present themselves as traces of microplastic in people’s blood, then abrasive protrusions on fingers, culminating in a more complete transformation where human skin becomes replaced by a shiny PVC exterior. The benignity with which these drastic alterations are received by the characters is further underscored by the scenes’ occurrence in domestic spaces also alien in their design to 21st-century readers.

Standing in contrast to the dark or sterile palettes more typical of dystopian fiction, the home spaces Albert creates throughout “Future Shock” are brightly colored. The home interior’s yellows and reds, as well as grid patterns, hint at construction materials that don’t presently exist. These choices tell the reader about the world’s affective and tactile changes over the millennia. This sensory world-building nicely complements the medical and scientific exposition that runs throughout, ebbing in and out of grotesqueries chronicling humanity’s plastic evolution.

The uncanny and horrific aspects of this story come through in the contrast between the radical alteration to human bodies, and the seemingly mundane existence of humanity’s far-flung descendants who are as equally concerned as their 21st-century counterparts with finding something good to watch on a screen. Albert exposes the relativity of normalcy here and human capacity to cope with change, ending the story foregrounding the queer domestic lives of PVC people rather than levying an environmental critique even as a final news report suggests another impending change to humanity.

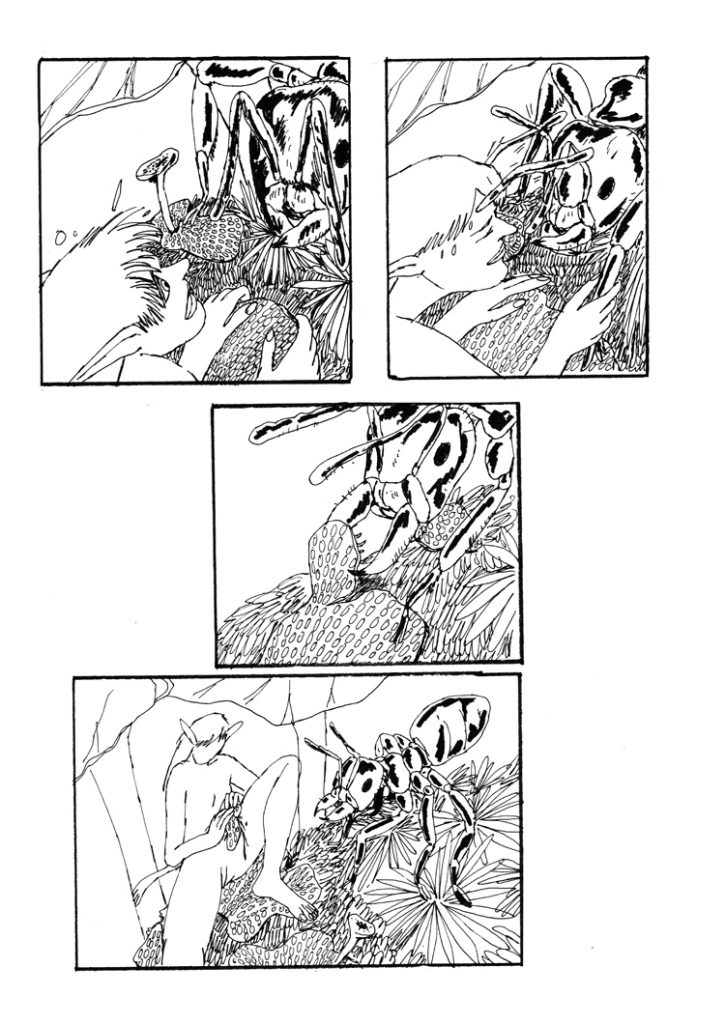

“Wet Earth”, the collection’s penultimate piece, demonstrates Albert’s deep interest in observing non-human activity. Here, Albert swaps out text-heavy sci-fi narratives for a wordless story that follows a small bipedal humanoid figure’s attempts to survive among birds, crabs, and insects on a marshy coast, employing an art style that utilizes black inks for photorealistic illustrations of the many beings in various establishing panels. “Wet Earth” will easily gain fans among folks who dig nature documentaries, as Albert renders various animals with a level of detail that evinces her extended time spent in study and observation of these creatures. While “Wet Earth” primarily takes a slice-of-life approach that follows these humanoid figures’ survival attempts, it shares with Albert’s other works a deep appreciation for the momentary connections between different beings, in part achieved through insert panels that linger on the physical touch that occurs between the story’s various living beings.

The blend of fantastical and Earth-based beings in “Wet Earth” invites the reader to ask whether their sympathies remain with the humanoid figures solely due to their appearance, even as they kill and consume much of what they encounter. One scene, in particular, depicts the humanoid characters in a sexual encounter throughout which they change physical form, becoming insects, and birds all the while maintaining intimacy. The scene induces a mixture of revulsion and sensuality, and I was left questioning what disturbed me about seeing an insect and humanoid creature makeout, a line of contemplation I haven’t previously considered.

Breakdown Press released this title under their new Library of Contemporary Comics line which aims to make contemporary works more widely accessible. Albert’s works, collected as they are here, demonstrate an artist with plenty to say and feel through. What I came away most attuned to after reading Seasonal Shift is how little of what is most tender and transformative to people can be visualized literally. Albert’s refusal to abide by a stable physical reality within these comics gives us entry into these spaces fluctuating between despair and ecstasy, a wave-particle of dazzling efficacy.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply