“Look, Hirosawa,” says Tetsu to his friend on the first day of high school. “You already said you wanted to be a big star in your intro.” In lieu of a classroom introduction, we receive a prologue that depicts an eight-year-old Hirosawa rapt before the televised adventures of his favorite tokusatsu hero, Tiger Mask, and the declaration that he too will “become a hero and protect women.” His friend’s reaction can therefore be read two ways. PEYO sows this seed of unreality early; we are invited to interpret Tetsu’s complaint as a reference to Hirosawa’s character introduction, breaking the fourth wall and establishing immediately the theme of performance. On the next page, Hirosawa steps boldly out of the panels, breaking the form to serve the manga’s function. He plans to join the drama club, to work hard and become the star performer – and already he is performing for us. Fukumaru, a friend from junior high, allows that this way of living makes Hirosawa happy. “But reality can be cruel.”

This Seven Seas release, the late PEYO’s Boy Meets Maria, follows immature and impulsive Taiga Hirosawa, who falls deeply in love with a girl on the first day of high school. Other students are quick to inform Taiga that ‘Maria’ is, in fact, a boy named Arima. Upon realizing that, his feelings remain unchanged. Taiga begins to re-evaluate his worldview while also trying to get closer to Arima during rehearsals for the school play. However, Arima is far from open to Taiga’s affections, and it becomes clear that both students are struggling with their roles and identities within and without their burgeoning relationship. Tentatively exploring their feelings and slowly revealing parts of themselves long-hidden, Taiga and Arima begin to address their respective trauma and challenge expectations.

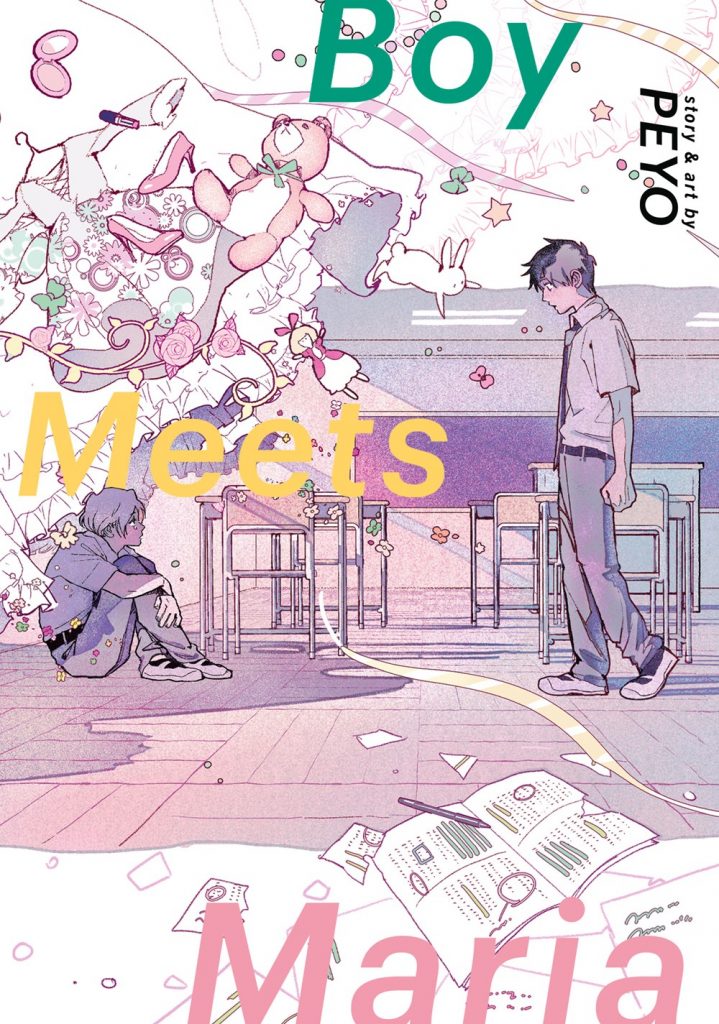

From a young age, Taiga has enforced on himself the role of a hypermasculine hero. Meanwhile, Arima stands in for female students in the drama club and, we later discover, is a member of the dance club. This juxtaposition is depicted on the book’s first page: Taiga’s bedroom in blue, replete with action figures and model cars; Arima’s bedroom in pink, with assorted cosmetics and soft toys. A white stripe bisects the image. The color scheme deliberately recalls the trans flag, and there are clues in both rooms to foreshadow the manga’s rejection of adherence to a strict binary, with bluish flowers and foliage decorating Arima’s room, and hints of pink in Taiga’s (including Tiger Mask’s cape). This first page also establishes another contrast between the two protagonists. A mirror is centered on each bedroom wall. Taiga meets his reflection’s eyes, but Arima is captured in profile. Already we see Taiga projecting a role onto himself, while Arima appears distant, dissociated. Taiga’s role allows him to look in the mirror; Arima must avoid it.

There is a sense in Boy Meets Maria of the need to challenge assumptions and expectations. Despite Taiga’s declaration of stereotypical heroism, we see an establishing illustration which depicts Arima (wearing a dress and a scowl) carrying a besotted Taiga bridal style, immediately foreshadowing his change of perspective. PEYO pushes this further both in the narrative and the aesthetics. Hanase Qi’s cover design is deceptively sweet. Arima cowers beneath frills and flowers and other stereotypically feminine accouterments, but soft pinks and blues offset what could be ominous. Sprinkled throughout the manga are boisterous Taiga’s interactions with an increasingly exasperated Arima. PEYO spends just enough time establishing this tone before shifting. Scenes of domestic abuse and illness, sexual assault and rape jar against visual comedy. This is not an unrealistic depiction of young people processing trauma and abuse. There are good moments – moments of levity and healing – and there are moments of pain.

Arima’s being so detached from the world results in scenes of, at best, inappropriate and, at worst, harmful behavior. Early on, Taiga refuses to see Arima as a boy, so Arima decides to give him “proof”. This linking of physical sex characteristics to gender reveals the characters’ continued reliance on a binary, on a system to help them categorize each other. Of course, as Taiga blurts out: “Even if! You have a d*ck, I still love you!” (Censoring PEYO’s) Later, a scene of spontaneous violence threatens the relationship Taiga and Arima have built. Thankfully, the manga relies heavily on the understanding that victims of abuse and trauma deserve support systems, not only comprised of their peers, but also those in positions of power willing to help. A teacher has been assigned to Arima as an advisor, and when he realizes that he is not experienced enough to help Arima, he calls for further support. It is a small moment, tucked into the corner of a panel, and we never see the resolution of the phone call, but the presence of at least one adult actively working to make a child’s life better helps combat the darker moments.

Taiga suffers homophobic bullying without really understanding it, and Arima suffers transphobic bullying, from students casually dropping slurs, to Tetsu’s claims that Arima “tricked” them, though an upperclassman steps in to refute this. Taiga’s aspirations – his sense of justice coupled with his intense compassion – allow him to recognize when his actions are less than heroic. He has perspective enough to acknowledge when his own assumptions have hurt people, and, by extension, when he needs to work to change his behavior. He expands his view of being a hero from simply needing to “protect girls” to something more fluid and complex. As the story develops, Taiga realizes how much he relies on the role, on the tacit belief that girls need to be protected by boys. If that is not the case, then what is his place in society? Arima struggles similarly. When a fellow classmate asks point-blank if Arima is a boy or a girl, the response is simple: “I can’t decide.”

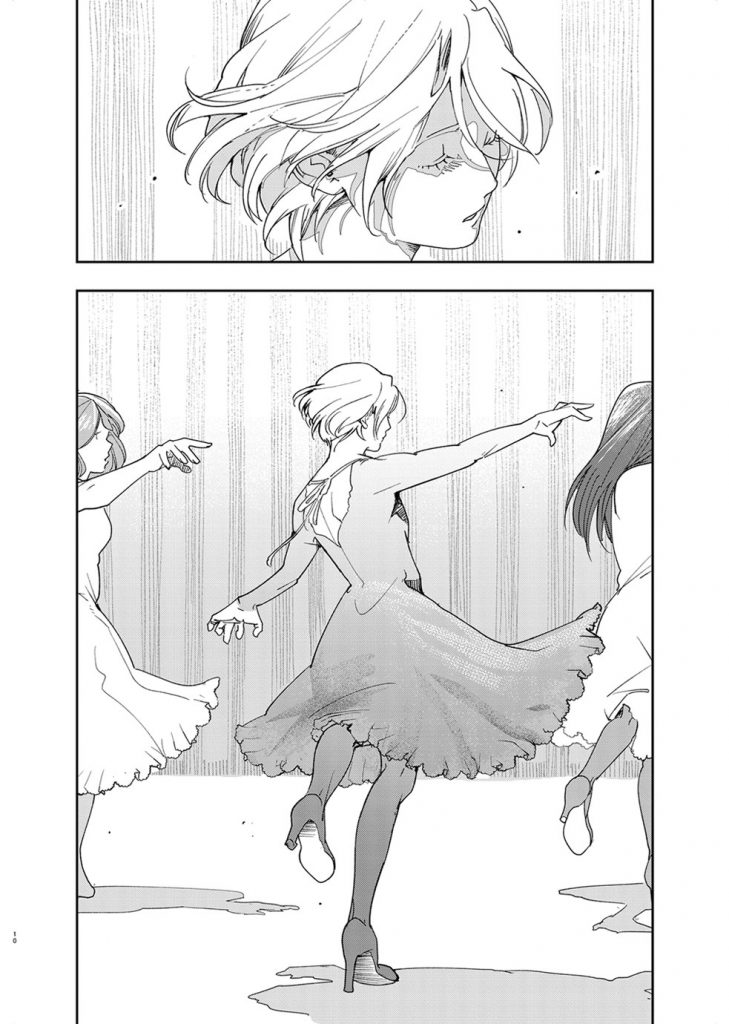

This binary is enforced at school and in the wider culture. Arima cannot comprehend how to fit into the world if there are only two options. Unlike Taiga, who flouts conventions to stride across the page, Arima at first appears fractured in panels: a hand here, a pair of eyes there, and a mouth not quite aligned – an uncanny effect. Onstage, performing a female role, Arima becomes freer, no longer confined by panels. Like Taiga, this performance allows Arima to reject expectations and shut out the world entirely. Like Taiga, it is a false presentation. Onstage, Arima’s trauma breaks through the façade. Panels become dark, borders thick and black, while faceless people twist and tilt and chant (“boy” from one observer, “girl” from another, and on and on). This moment of breathless, awful panic reduces Arima to a rude and stunted sketch, alone and mocked at center stage. The performance – a place of refuge – fractures.

Arima’s reliance on roles to play began early. Arima’s first name, Yuu, takes its kanji from the words ‘haiyuu’ and ‘joyuu’, meaning ‘actor’ and ‘actress’ respectively. This portentous name was chosen by a mother living vicariously through her child. Now, Arima continues to perform both on and offstage out of necessity. Treading the boards as a boy triggers flashbacks and panic attacks. As Arima states: “… it makes me want to reject how I was born. The male part of me. It makes me want to reject all of myself.” Arima has perspective enough on the situation to place the blame squarely at the feet of those who caused the hurt in the first place, but now also struggles to see the way forward. Arima pushes everyone away in an act not only of self-preservation, but also as a way to protect them from becoming “messed up”. To this end, Arima upholds dual façades: the vibrant, untouchable girl onstage; the brusque, aloof boy offstage. His clear desire not to perpetuate a cycle of abuse makes the pretense paramount.

Boy Meets Maria’s protagonists rely on performance. Trauma suffered in their early years informs their need to project images into the world that might protect them from further harm. PEYO explores in deeply upsetting scenes the level of pain through which both characters have suffered. Rather than brushing their trauma aside, we are forced to live through it with them before confronting the painful truth that there are no easy answers. Both Taiga and Arima need support systems, they need understanding and compassion – and they find all of this with each other, with friends, and with sympathetic adults – but their trauma cannot be resolved over the course of a school year. PEYO’s dynamic artwork and writing combine to create a story about trauma, identity, gender, and performance (and gender as performance) that is sweet and messy and, at times, deeply painful, but ultimately optimistic.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply