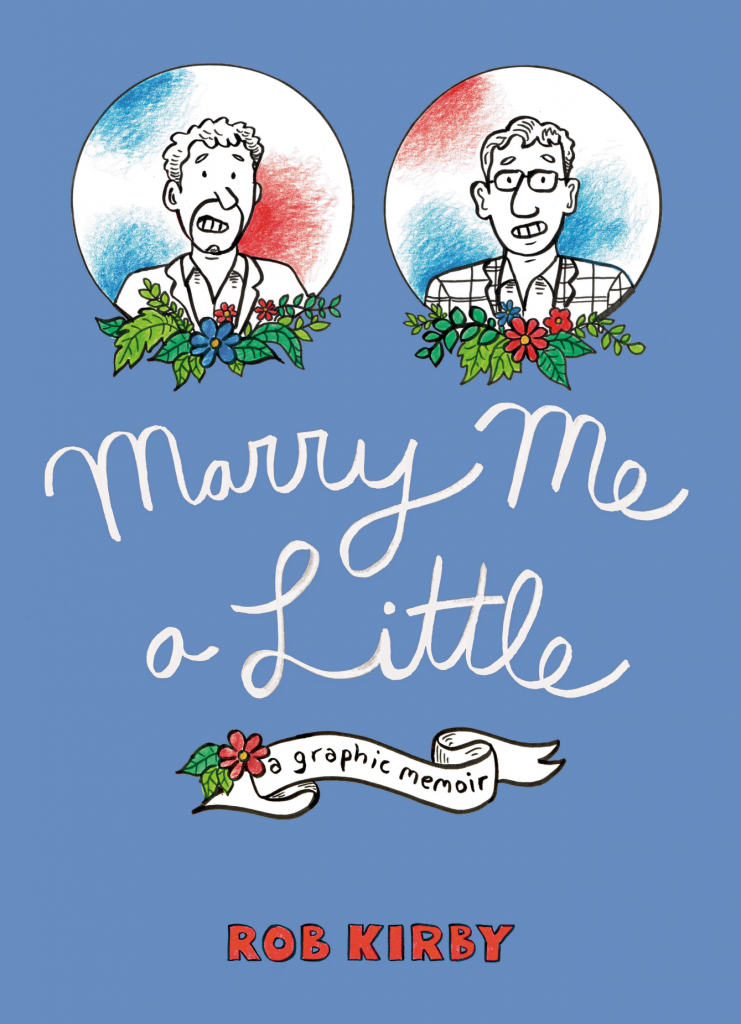

At first glance, Rob Kirby’s Marry Me A Little feels a little thin and a little light to justify it being a full-length memoir. A close examination reveals that it is less a narrative than a series of pleasant anecdotes. Two nice men, now allowed to legally get married to each other, do just that and have a lovely time. There are no hindrances on their wedding day, no melodramatic events before or after. There’s no story here, per se. It ignores every convention of genre, as there is no real conflict or resolution to the conflict.

This is exactly the point.

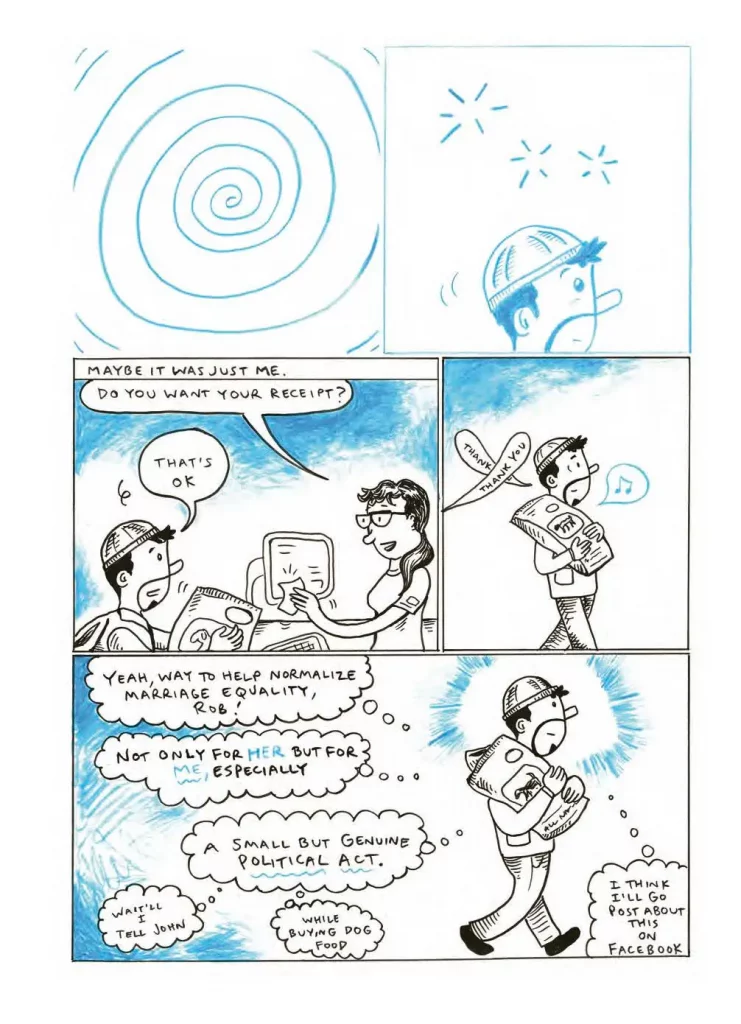

Kirby is almost apologetic for writing this story even as he’s telling it. Not just for how pleasantly conventional and fun his wedding day was, but for even participating in an institution that he was always leery of in the first place. He feels a pull between queer anti-marriage rhetoric that decries it as a conservative, patriarchal relationship structure and wanting things like equality under the law. Beyond that lies the gnawing feeling that rights like this could be taken away at any moment, something he explores toward the end of the book. In the first scene, Kirby is buying dog food and gets a discount when he says it’s under his husband’s name. It’s the first time he referred to him as his husband, and he realizes that this completely ordinary interaction with a cashier is a small but pointed political act. It’s normalizing gay marriage, once a political football exploited ruthlessly by the right in a manner similar to trans rights today. It is making concrete the idea that gay marriage harms no one, does no damage to any societal institution, and is fundamental to the idea that the “gay agenda” is simply wanting to live a life without persecution.

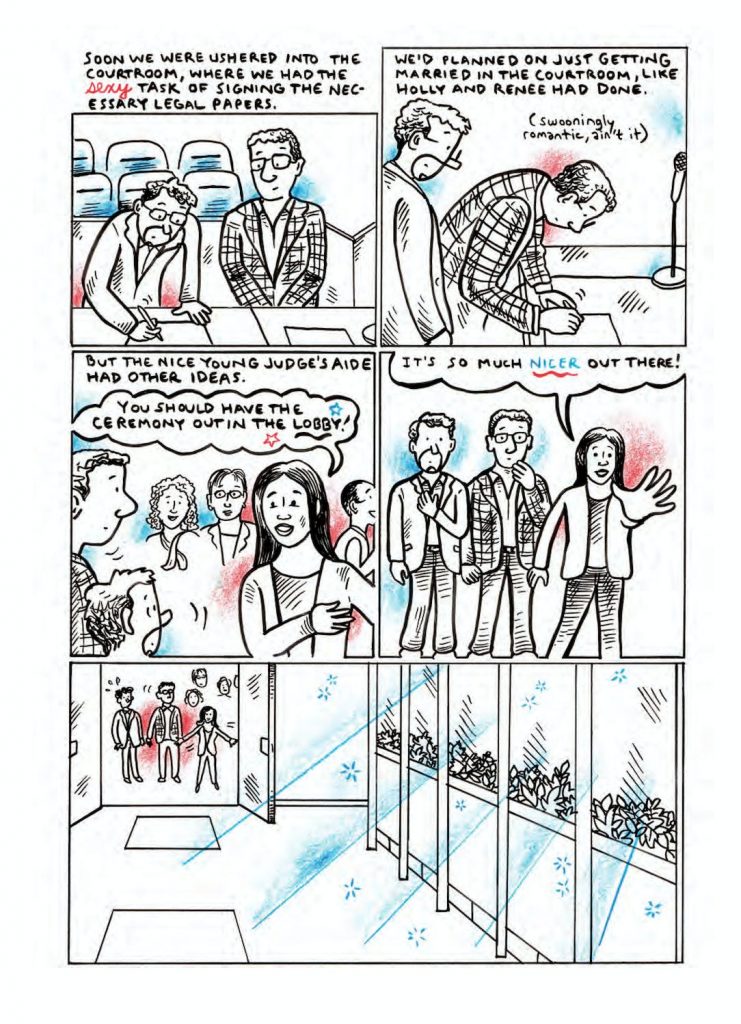

Kirby could have easily made this book a polemic and gone much further in arguing these points. However, this would defeat the purpose of the narrative: getting married wasn’t a big deal. The marriage didn’t define the relationship he had with his husband John; they had been monogamous partners for well over a decade before gay marriage became legal. Over the course of the book, their lives don’t change much as a result of getting married. They are simply given the opportunity to make a life together: sell their house, move into an apartment, grieve when their beloved dog Ginger dies, and a thousand other mundane things straight couples have been able to take for granted for years.

For marginalized groups, very little can be taken for granted, however. If nothing else, this pleasantly-told story is a snapshot of a particular moment in time of a mundane act that nonetheless had radical implications. The fear of rights being one day lost is precisely why this book is so important. I have no doubt that someone, somewhere, will try to ban Marry Me A Little from a public library. The reality, of course, is that the book is entirely inoffensive. It’s a book about committed relationships with a touch of romance, and it’s in no way sexually explicit. None of that will matter, but what’s important is that Kirby got to share these anecdotes publicly. It’s important because small narratives like this matter much more in the future than they do in the present.

For marginalized groups, preserving that history is crucial because it’s so easy for it to be erased. Kirby himself discusses a bit of this history in the course of Marry Me A Little, detailing a bit of the lives of Jack Baker and Michael McConnell. They were a couple in the early 70s who fought to get married and used a bit of subterfuge to get a license. He also described a documentary about Proposition 8 in California, which banned gay marriage until it was challenged by two different couples.

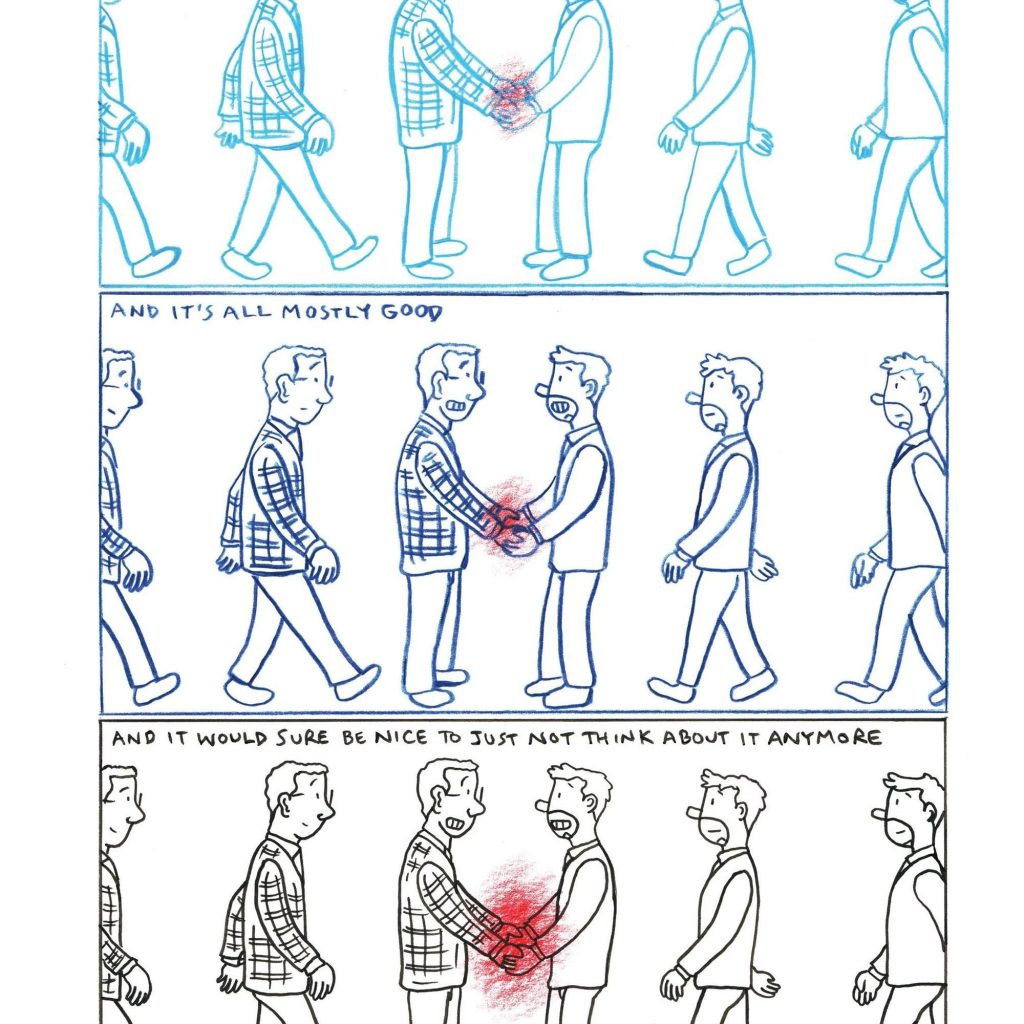

Kirby emphasizes that he never thought about getting married until it became legal for him to do so in Minnesota. He didn’t want to think about it, yet being at the center of historical progress is something he simply couldn’t ignore or take lightly. He doesn’t frame it as a duty, per se, but he’s aware that this public and legal institution is something that a lot of other people had fought for. While not the be-all, end-all for all queer people, it still meant a lot to a lot of people. Kirby also points out that as a white, middle-class male, he was in a position to be dismissive of arbitrary rights not being available to him, and knew that he had to resist that dismissiveness. There’s a beautiful sequence in the book where Kirby, who uses red and blue as accents throughout, is walking toward John as a ball of red crayon is furiously scrawled over them, representing the reality of homophobia and the right’s eventual backlash. As though he was drawing paper dolls, there’s another page where he scrawls in his face and John’s face on two groom paper dolls, asking if they took this for granted.

After the first part of Marry Me A Little finds Kirby wrestling with his perspective about marriage, the bulk of the book is essentially giving himself permission to be indulgent in talking about the big day. The planning, him surprising himself by wanting to get dressed up, the musical playlist, and a pop culture exploration of how movies about weddings are always melodramatic are told with Kirby’s usual breezy charm. Family and friends showed up. There was a nice dinner. It was a nice day for nice people, and while not exactly compelling reading, Kirby adds humorous asides and jokes to keep things moving. (In the interest of full disclosure, I’ve been friends with Kirby for quite some time and was credited in the acknowledgments.)

And yet.

There’s a sense, as Kirby is amazed when marriage is legalized in all 50 states, of waiting for the other shoe to drop. That there’s no such thing as a happy ending, or any ending at all, really. The reality for marginalized groups is that any progress made in the eyes of the law and the culture at large can easily be rolled back. Kirby rapidly rolls the calendar forward from that moment in time in 2013 into the Trump years, COVID, the execution of George Floyd, job loss, the death of his dog, moving, and other peaks and valleys. Through it all is John, the days stacking up to form a strong foundation that’s weathered tragedy and accumulated joy. Kirby points out that this is what’s intrinsically most important, but the reality is that there are existential threats to freedoms that must be opposed. Being married, buying dog food and mentioning your husband while doing it, fixing a billing issue that mentions your husband are all forms of daily opposition. The personal is not only political, but the quotidian is a form of protest. The title of the book is a joke that Kirby makes, trying to downplay the significance of marriage as an institution in his life, but the reality is that in this case, simply getting married to John was getting married a lot.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply