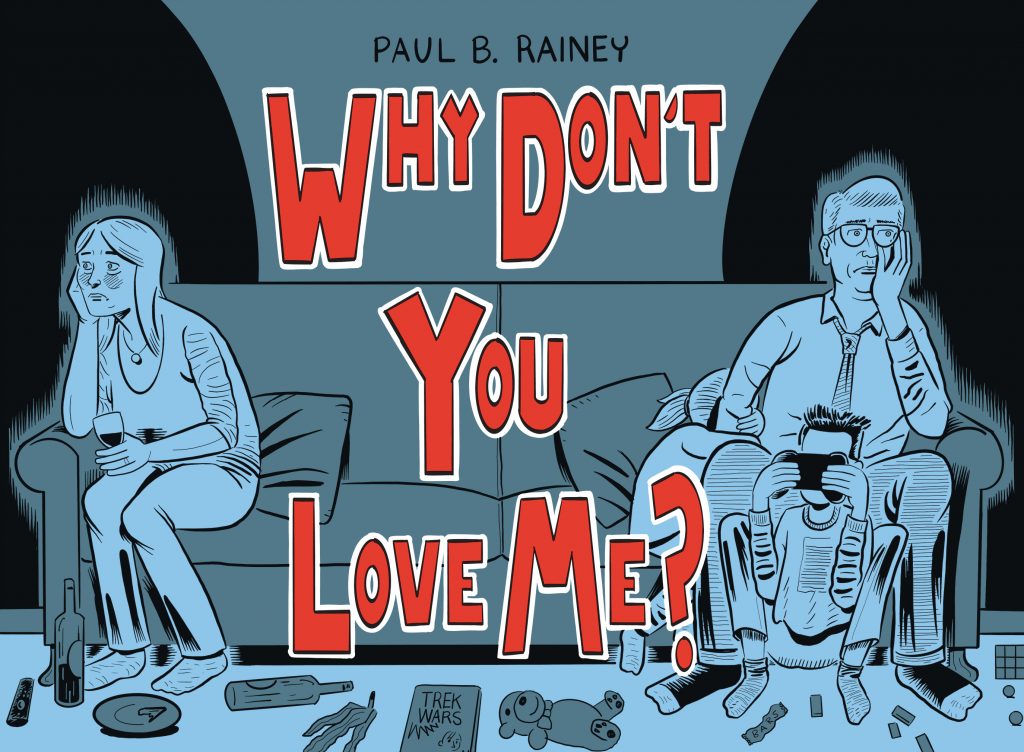

Paul B. Rainey has made it difficult to review his latest work, as there is not merely one major development a reviewer shouldn’t spoil, but there are the consequences of that development that lead to another significant event. Part of the enjoyment of this comic is tracking through those major shifts on one’s own. Thankfully, that’s only part of what this book has to offer. Even if I were to tell you the entire plot of Rainey’s work—which I won’t, I assure you—the questions he explores would still be enough to motivate most readers to pick up his work.

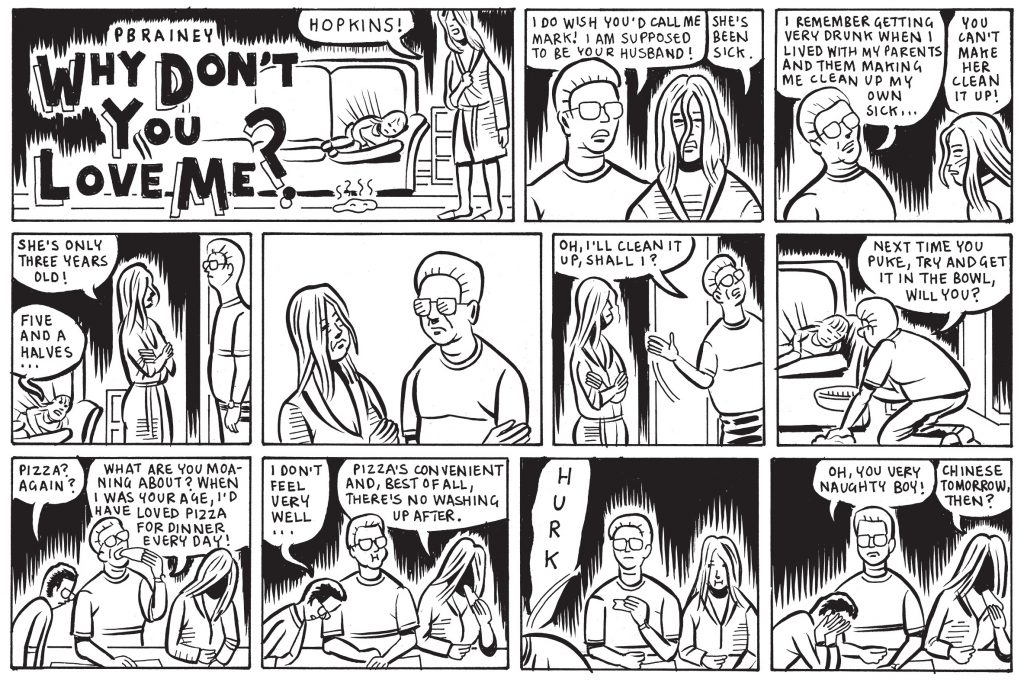

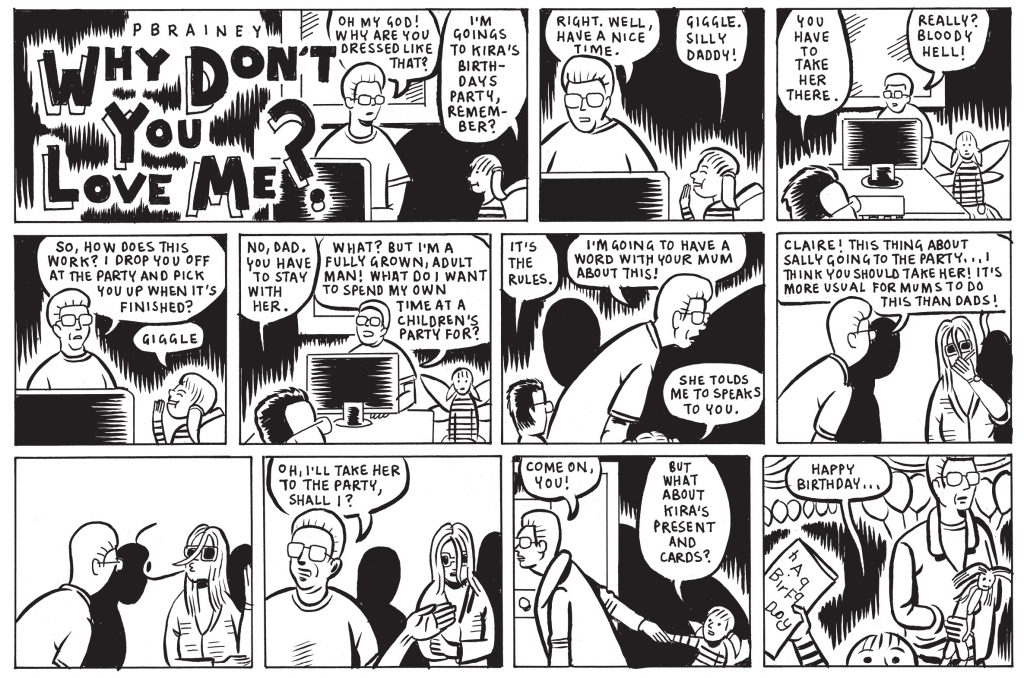

The first part of the book is clear enough: Mark and Claire are living together, perhaps married, with two children, Sally and Charley (though Mark almost always refers to Charley as Tommy, Mark’s brother’s name, as Charley looks like Tommy did when he was young). Their relationship with one another and with the children, however, isn’t going well. If Claire isn’t clinically depressed, she shows all the signs of being so, using alcohol to self-medicate. There are weeks where she doesn’t leave the house, counting on Mark to bring home wine and/or beer. She doesn’t engage with the rest of the family much of the time, even lying to get out of obligations, such as going to see Mark’s family.

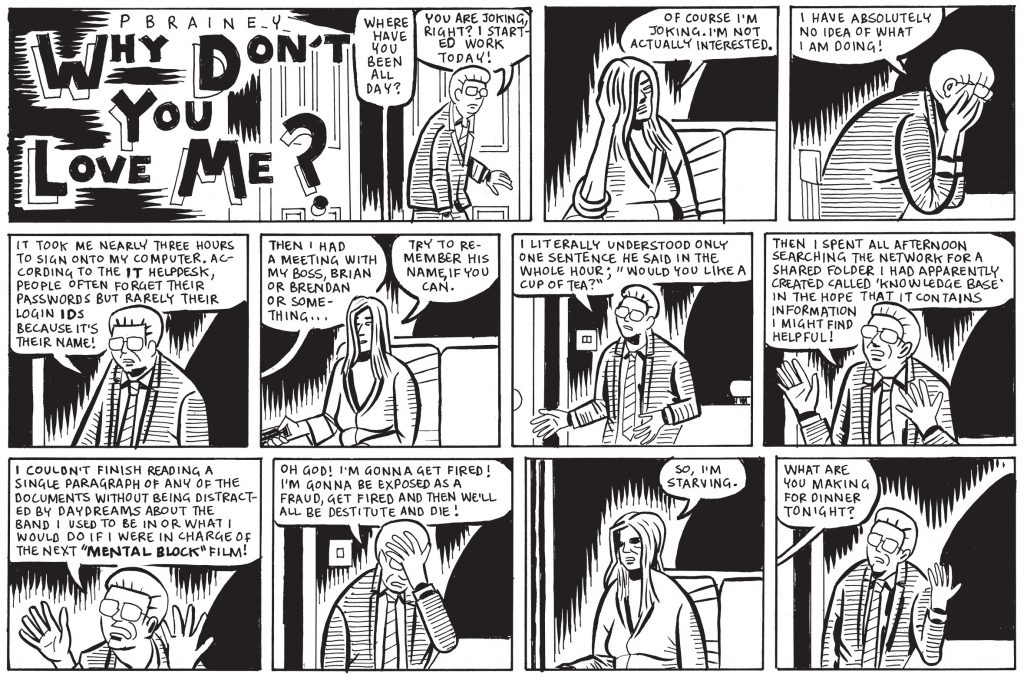

Mark struggles early in the book, as he’s been off work for several weeks, seemingly for a disability, probably depression, as well. That’s the reason he gives to his doctor when he negotiates for two more weeks before he has to go back to work. He has a job as a web manager, but he claims to know nothing about how to do that job. He even insists he’s a barber. However, once he goes back to work, he finds he’s better at the job than he expected even though he seems to be doing nothing other than dropping jargon at the right times and allowing Suresh, who works under Mark, to do all of the work.

Their relationship is strained to the point of breaking, though neither of them seems all that upset by it. At one point, in fact, when Claire has stopped drinking, partly due to Mark’s leaving her for several days, Mark has brought her wine, thinking she would want some. She tells him she would rather him pour it all out. As he pours one bottle after another down the kitchen sink, she comments, “There. Just like our ‘marriage.’” Both of them simply laugh. That ending is reinforced by the structure of the book, as Rainey has printed each page as if it’s a separate comic strip, much like one might have found in the Sunday newspapers. Each new page has a new title spread, as if it’s a weekly or daily strip, even though the storyline continues on from one to the next. However, this structure makes each ending feel a bit like a faux-sitcom ending, where the final panel feels like it should (or, at least, could) end with a joke as a traditional comic would do. It’s almost as if Rainey has combined the strip format with a stereotypical strip from the mid-twentieth century about a family that doesn’t get along, but without the joke, subverting that setup to ask more significant questions.

This strife between Claire and Mark has a clear effect on the children, who seem like afterthoughts for the two of them. They go weeks without taking the children to school, but also barely feed them. It takes the school’s having to call Mark in before he begins to try to take care of them, though, even then, he barely acknowledges their existence and continues to call Charley by Tommy’s name. It’s only when Claire meets Karl, the father of one of her children’s friends, that the children begin attending school more regularly, as Claire is clearly attracted to Karl, and she believes the opposite is true. Mark also meets a woman when he is out walking the dog, and she makes a pass at him. That woman tries to encourage Mark to leave Claire and begin a relationship with her, but Mark chooses not to. He tells her, “The thing is, I don’t understand how it is we fell in love with each other in the first place. It’s vital to me that I understand how that happened. If I leave her now then I will never find that out.” That question is one the reader has probably been asking since the second or third page of the book.

At this point, the reader probably has other questions, as well, given the inconsistencies in the narrative. Claire asks her mother about a previous boyfriend, but the mother has never heard of him. Mark finds a guitar and starts playing it, though Claire has no idea he can do so. Claire asks her mother how her father is doing, even though he’s dead. Mark calls up a friend to go see a movie, and the friend says it’s been ten years since they last talked. All of those concerns dovetail with how Claire and Mark treat each other and the children, leaving the reader to wonder if there’s something else that’s wrong with this family.

That’s as much of a plot as I can give, as saying more would ruin the rest of the enjoyment of the book. However, I can say that, by the end, the reader will have plenty of significant questions to chew on. On one level, Rainey is dealing with the basic question of human connection, as the title conveys (even though it doesn’t come from either Mark or Claire, at least not directly). Readers can see an unhappy couple who desperately want connection, but they don’t find it with one another or really anybody else, leading to the ways in which all of us long for such connections and often struggle to find them. While most of us don’t treat romantic partners or family members as Mark or Claire do, we often choose to take such people for granted.

That idea leads to the question of how we define success and happiness. Mark and Claire have a decent life, but neither of them seems satisfied by it. Early in Why Don’t You Love Me, this lack seems due to the depression both characters appear to be struggling with, but as the novel progresses, Rainey moves his characters beyond that condition. Instead, they both, at various times, don’t see the positives they do have in their lives because they are either looking toward a romanticized past or a future self that could be different. Rainey complicates their search for a different self. as people around them don’t seem to want them to be different. When Mark expresses an interest in a different career, those around him aren’t encouraging; similarly, when Claire tries to reshape her life, others try to push her back into the person they already see her as.

Underlying all of these contradictions and questions is one of the most significant human questions, the eternal question of fate versus free will. While both Mark and Claire change in rather important ways in the book, there are ways in which the world doesn’t change and doesn’t seem able to change. Rainey doesn’t seem pessimistic about that overall lack of change, even though a world that could change would make for a better place, both in his book and in the world we know. Without that possibility, though, Rainey seems to come back to human connection. Throughout the work, which Rainey draws in black and white, he often uses dark or plain white backgrounds. When there are more detailed backdrops, they are simple, as if he wants the reader to focus on Claire and Mark, as well as any other characters in any particular scene.

Rainey’s focus is both on the macro and micro level, then. While he wants readers to ask large questions about existence and the world, he points toward individuals as answers to those questions. Whether his characters have choices or not, he seems to be saying they can at least be engaged with those around them; they can at least find one moment here or there to enjoy the company of another human being. After the last strip, readers aren’t going to have all the answers they need to answer the questions Rainey is asking. In fact, they won’t have many answers at all, though they will have theories. More importantly, though, they’ll have questions that will lead them to examine their own lives. And they’ll have had the time they spent in Rainey’s world, with Claire and Mark and the rest of the characters. Whether that was their choice or not seems irrelevant.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply