Emma Grove starts her graphic memoir with an author’s note that lays out her focus on what actually happened in terms of actions, but especially in terms of dialogue, which will make up the bulk of her work. She explains why some of the dialogue will be repetitive, as it often is in real life. She even ends the note by writing, “No dialogue has been invented or tailored to suit the author’s point of view or for storytelling purposes.” And then Grove tosses the reader into an introductory scene with no context that will only make sense much later in the book. Both the author’s note and introduction set up the themes that will dominate the book.

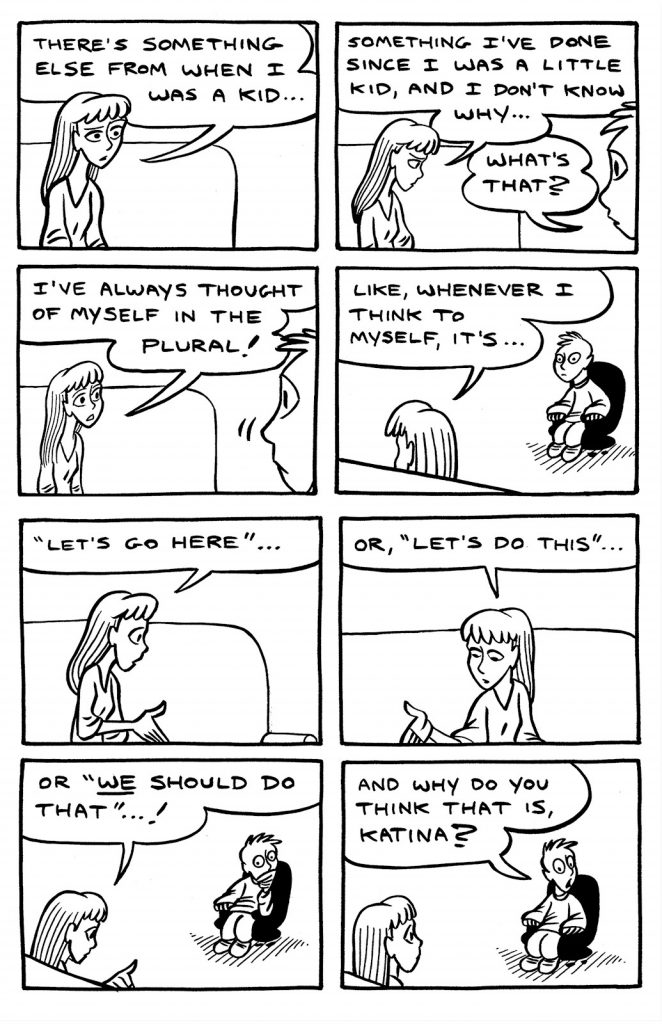

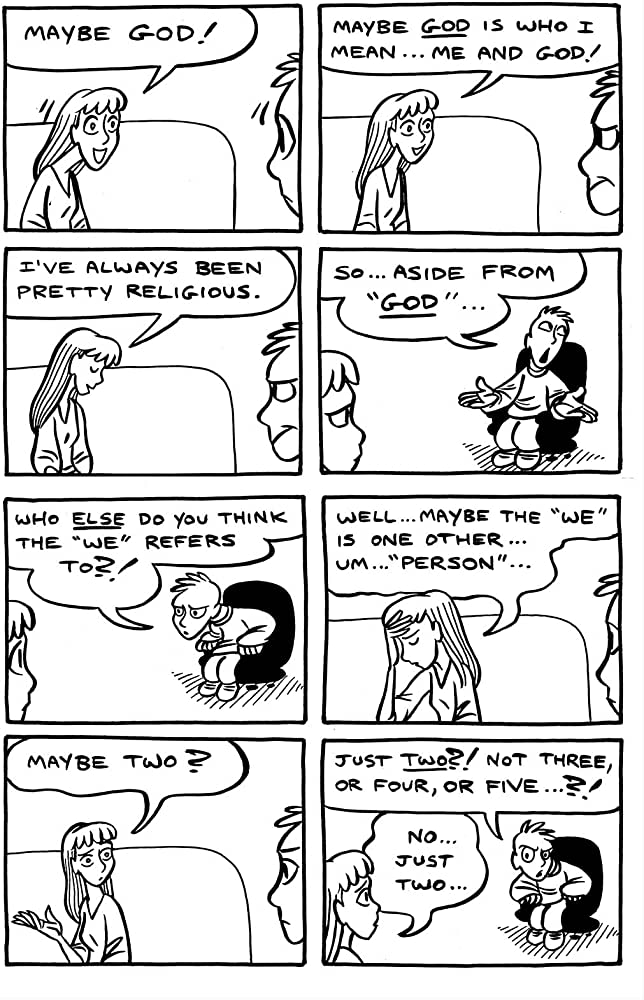

First, much of the work is dialogue, as there’s little plot really to speak of. The main development comes from the main character’s (named Ed) exploration of his personality and desire to transition. The overall narrative is that Ed (or Edgar) wants to transition to a woman and so must see a therapist before being allowed to do so. During those therapy sessions, it becomes clear that Ed not only desires to be a woman, they’re struggling with Dissociative Identity Disorder (D.I.D.) due to trauma in their childhood (Author’s Note: I have tried to be consistent in my use of pronouns: when speaking of Emma Grove, the author, I use she; when speaking of Emma or Katina as characters in the work, I use she, and I use he when referring to Ed; I often switch to they when talking about Ed/Emma/Katina as characters, given the complexity of personalities there; when in doubt, I use they. Any mistakes are solely mine, and I apologize in advance for them.). Thus, not only does Ed present as a male, while wanting to transition into Emma, a female, there is also Katina, the third person of the title. Katina is a personality Ed/Emma has developed to protect themselves from the trauma of their childhood.

At least three-fourths of the work consists of therapy sessions between Ed/Emma/Katina and Toby, the therapist who can sign off on the surgery required for transition. However, Toby spends much of the time disbelieving Ed/Emma/Katina, often questioning whether or not their desire to transition is real, but, more importantly, questioning whether their D.I.D. is even true. Instead, Toby believes they are simply pretending to have D.I.D. as the manifestations of the disorder are so in line with the textbook definition, a problem that becomes even greater when Toby catches Emma looking at the books in his office when he has stepped out for a moment.

Grove’s focus on the veracity of the dialogue, then, makes sense, as Toby is often abusive, both in his lack of belief in his patient’s explanations and in his questioning of their desire to transition. When Emma begins to fade away at one point, almost switching to Katina, but coming back as Emma, she responds with thanks to Toby for bringing her back. However, Toby responds, “Well, now I know you’re faking it!” When she questions him, he continues, “This is just too textbook!” He then uses the definition of D.I.D. almost as a cudgel that he wields against Emma, while she is struggling simply to breathe.

To Toby’s credit, there are moments where he tries to recommend Emma see a specialist in D.I.D., but she chooses not to. Instead, they stay with Toby because they feel they’ve built a relationship with him. Ultimately, they realize that relationship is an unhealthy one, and they find a therapist who is much better suited to deal with their D.I.D. and childhood trauma. However, Grove doesn’t dismiss the personality that manifests as Katina, the one she developed to deal with that trauma. Instead, she dedicates the book to her and ends the book with a section where Katina defines a friend. She says, “You do things together…you look out for one another…you never leave your friend in the lurch! You look out for your friend…you protect your friend! You never hurt your friend! You would rather lay down on the road and die than ever hurt your friend! And you would give everything…everything…to keep your friend from being hurt! You would give your own life if you had to…you’re always there when your friend needs you! You love your friend, Toby!” Katina talks about how she and her friend (Emma) plan to write a book one day; of course, that book is The Third Person. Even though Katina ultimately sacrifices her life for the mental health of Emma, it’s clear that Emma and Ed needed her to help them through their suffering.

Katina is Ed and Emma’s friend in that they developed Katina to protect themselves from the abusive childhood they suffered. As a boy, Ed didn’t behave as a typical boy, knowing from as early as four years old that they were a girl (in a flashback at age two, Edgar also believes his penis is supposed to be “in,” so it might be as early as two years old). Grove relates a flashback to when she learns to write her name, and her grandmother forces her to write with her right hand rather than her left, the one that’s more comfortable for her. In the same scene, Edgar believes their name is a girl’s name and is confused when her grandmother says that it’s a boy’s name. Given that they believe they’re a girl, the assumption around the name Edgar makes sense. The combination of the confusion over the name and her grandmother’s forcing her to write with her non-dominant hand reinforces the idea that her grandparents and society will force Edgar to try to behave in line with their expectations of masculinity.

Society reinforces those expectations in the scenes that take place outside of the therapists’ offices. Both before he visits Toby and during the therapists’ visits to be able to transition, Ed struggles at his job at a restaurant. He wants to be able to work there as a woman, but Vikki, his manager, makes it clear that he cannot, despite how good he is at his job. Emma tries to find work as a woman, but, after a month, it becomes clear that nobody will hire her, so Ed has to return to the job, despite the emotional and mental toll it takes on him. He needs the money to pay for the therapy sessions, but the only way he can get that money is to create more psychological dissonance.

One of the most effective ways Grove communicates this disconnect is how she portrays the multiple personalities within herself. Not only does she draw the three ways she presents herself differently, but they also exist within each other at times. Especially when alone, Ed might be driving to work, but an additional head will appear out of the back of his head, and Katina will speak. At times, when one of the manifestations blacks out—which happens when they dissociate and switch personalities—the reader will get to see two of the personalities interact to decide which one will manifest to talk to Toby. Otherwise, Grove uses black-and-white artwork to keep the focus on the dialogue. The one exception is when Emma has gotten a job in a call center and seems much more comfortable as a woman. She goes to a club on “Girl Twirl” night and finds a group of women to dance with. As they are about to leave, she requests “99 Red Balloons,” and Emma dances completely and utterly as herself, all in color. However, rather than leave the reader with the impression that her life is now perfect, as the song ends, the scene shifts back to black-and-white, as the other women have moved to their own groups as they prepare to leave. Emma still misses Katina, her friend.

There are scenes in the work where Grove shows the importance that art and books have played in her life, which reveals the irony in the conflict between her and Toby over the textbook. During his abusive childhood, Ed would take comfort in books, as they were a neutral activity, not as clearly tied to gender as some of the other interests he had. He tries to use the books as a refuge from his abusive grandfather, but the grandfather ultimately forbids Ed from reading, as well. His grandmother, though, to distract Ed from bothering her, gives him some tracing paper and tells him to fill it up. Through the process of tracing, Ed ultimately learns how to draw. When he is six and a boy tells him that the other boys look at him strangely, Ed asks if the boys “hate [him] because [he] can draw really well?” He doesn’t understand the ways he doesn’t fit the masculine stereotype. Grove sets up the artist she will eventually become, though it’s not clear early in her life that that will become a way for her to process the trauma she has endured.

One other minor idea she develops is her connection to religion. Given the way some dominant strains of Christianity portray the LGBTQ+ community, it seems that Grove wants to remind readers that there are trans Christians and that she takes her faith seriously. Several times during the therapy sessions with Toby, they will bring up that faith or react when Toby says something negative about God. When Emma is trying to convince Toby that she’s not made anything up, she says, “If you know how much God means to me…or maybe you don’t, I dunno…but, right hand to God, I swear I haven’t ‘made up’ anything with you!” Near the end of the work, when they have transitioned to Emma (the scene right before she goes to the club to dance, in fact), she goes to church, receives communion, and shakes hands with the priest on her way out. These brief mentions reinforce the idea that Emma has moved toward an integration of who she is: a woman who can live and work in the world and who values her faith.

Grove openly shares her struggles to get to that place of integration, revealing all that prevented her from working toward a core self. They endured an abusive childhood and abusive therapy, both from places that were supposed to be safe, but they ultimately find a therapist to help them process their trauma and work toward a place of wholeness. Given how our society continues to treat the LGBTQ+ community, Grove’s work is an important story for all readers, well-told and well-executed and well worth readers’ time.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply