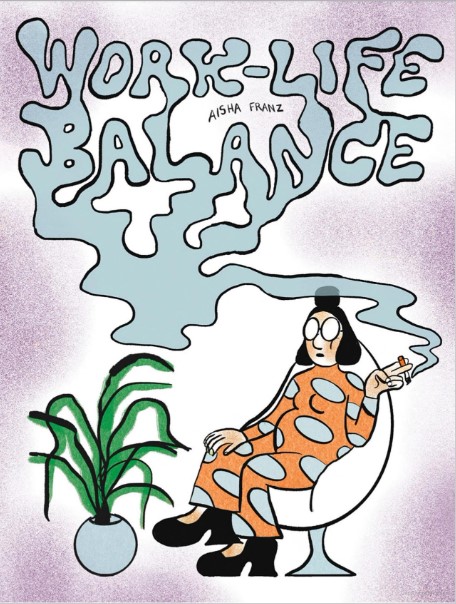

The focus of Aisha Franz’s graphic novel Work-Life Balance is not the plot. It’s not even the characters. Instead, it’s ideas, mainly ideas Franz wants to satirize. As in most dystopian or satirical works, Franz doesn’t develop her characters or make readers wonder what will happen next. Instead, she presents vignettes from the lives of three characters—Anita, Sandra, and Rex—all of whom primarily connect to one another because they visit Dr. Sharifi, a therapist. There are moments of other connections, but they are less important.

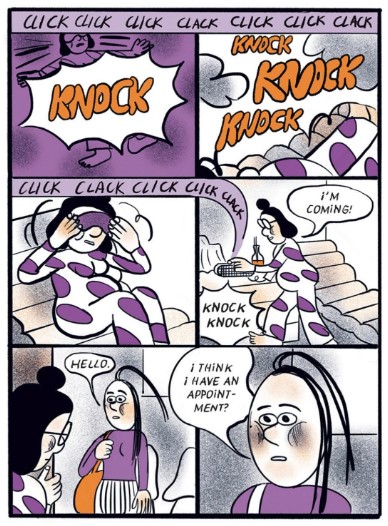

Franz certainly satirizes therapy through her portrayal of Dr. Sharifi who seems much more focused on herself than her patients. At one point, when Anita is in a session, Dr. Sharifi is yawning and typing on her phone. When Anita yells at her for not paying attention, Dr. Sharifi simply tells Anita to calm down, then offers her a pill, one of her frequent methods of dealing with patients. In fact, in a meeting with Sandra, Dr. Sharifi offers her a pill and asks, “Are you ready for the ritual?” implying that she provides a pill every time Sandra comes to a session. Franz uses such scenes to mock some therapists’ reliance on medicine rather than knowing and helping their patients.

When sessions go badly, Dr. Sharifi doesn’t react or adjust her behavior. After Anita storms out when Dr. Sharifi is ignoring her, the doctor simply continues checking her phone, then lighting a cigarette. Sandra becomes infatuated with Dr. Sharifi, imagining making a meal for her, a problem Dr. Sharifi is either unaware of or unbothered by. Sandra, however, runs out of appointments (the “therapy bundle” her employer purchased), but she hopes she can talk to the doctor as a friend. Dr. Sharifi is clear that’s unacceptable, but she offers no guidance to Sandra, such as finding a therapist she could afford. She doesn’t seem to care about her patients as people, just as a job.

Franz uses Rex’s storyline as a way to satirize online therapy, as Rex visits such an online space several times. Rex says he is there to see what the competition is up to, as he is a computer programmer/hacker, and he designed the program Agileal is using, though they never paid him for that work. The online therapist seems to be Dr. Sharifi, given the avatar, and she doesn’t seem concerned that Rex has hacked into the system or that he is unwilling to talk. In fact, she says, “I’m being paid for the time I’m logged on. You can look around as long as you want.” Her comment is a clear reference to the title of the book, as Dr. Sharifi seems to view her job simply as a job, a fairly healthy approach to keeping boundaries. However, she seems so detached as to be unhelpful, with her balance clearly shifting to her life, not to the work she should be doing to help those who come to see her.

Franz breaks her work into short sections that move between the individual characters who visit Dr. Sharifi, with each section ending with a sketch that wraps up that section, and the next, beginning with a more realistic drawing that sets up the next section, often of the location where the next part will take place. Franz makes good use of a wide palette of colors in each section, using purple for Sandra’s flashbacks, blue for Anita’s, and green for Rex’s time in the virtual therapy world. These colors mirror what the characters are wearing in the present day and/or real world, creating a subtle connection between their present and past, as if they don’t or won’t ever change. They all connect to Dr. Sharifi in the same way, as the color of her outfits match what Anita and Sandra are wearing, and she appears in the green virtual therapy space that matches Rex’s shirt. In the same way that they stay the same, she simply mirrors them, providing no help of any substance.

Those three characters need a good deal of help, as they all have real problems, many of which stem from the work they do and their approach to it. Anita is a sculptor, but she makes a living by creating practical objects local stores can buy and use rather than what she views as real art, that which real artists create. She’s struggling with jealousy, as her studio mate has recently landed a major show, in addition to several invitations to artist residencies, including one in Iceland. She emails Anita to ask if Anita can deliver one of her sculptures to the gallery, and Anita begrudgingly complies.

Franz uses Anita and her experiences to satirize the art world, both her education and the ways people speak about art. During one of Anita’s sessions with Dr. Sharifi, she shares a story from her experience in art school. Her professor, during a critique of her work, calls the work “insane,” adding, “not even the slightest hint of irony!” The professor then proceeds to tell Anita about her chances of success: “Let me remind you . . . only six percent of graduates will have successful art careers. And you unfortunately will not be one of them. I find that the naked truth makes the best advice. You should be thankful that you’re hearing it now while you can still turn back.” He offers no critique of her work, no way for her to improve and grow; instead, he simply demeans her.

Later, at her friend’s exhibit, Anita mocks the type of people her professor would admire. She overhears two people praising the work she delivered, and she interjects into their conversation: “The artist’s handwriting is undoubtedly recognizable. It’s a powerful synergy of traditional craftsmanship and the subversion of contemporary art. This is a piece of utter devotion.” Rather than realizing that Anita has said nothing of substance, they praise her comment, with one even asking who she writes for. Franz shows the hollowness underneath much of the contemporary art scene, both in what passes for great work and in the ways people talk about that work.

Franz uses Sandra to satirize contemporary work culture. She is clearly bored with her job, even complaining to Dr. Sharifi that she doesn’t have enough authority or agency to do meaningful work, but she is paid much more than an assistant, which is the type of work she ends up doing. She wants to find more fulfillment outside of work, so she makes videos she posts on a YouTube-like site. Like almost everybody else who creates such content, she constructs and crops them to present the appearance of reality, as when she has the video capture her waking up and beginning her morning routine, only to hide the truth, such as her putting on make-up before she went to bed, so she would be more visually appealing to her viewers when she woke up. On the one hand, then, Franz satirizes this type of content for not representing reality clearly, but she’s also created a character who needs another output for her energy, as her work is not challenging her.

However, Sandra’s lack of awareness of reality becomes much more problematic in the scene following her editing her morning routine video, as the company is suspending her due to a sexual harassment allegation. According to Sandra, the relationship was consensual, but her conversations with Dr. Sharifi reveal that she coerced her co-worker into it by her threatening to accuse him of improper behavior. Sandra’s lack of ability to see reality has disastrous consequences, as she ultimately loses her job, which spills over to her videos, where people post comments about her losing that job because of sexual harassment.

Franz also satirizes start-up culture through Sandra—who works for Agileal—and Rex. When management confronts Sandra about the allegations against her, they talk in vague terms, saying that “we’re aware that this situation can be interpreted in different ways” and that they’ve “decided against immediate termination,” putting her on “unpaid leave” instead. Only later does Sandra find out they’ve actually fired her and banned her from the office. A different employee at Agileal takes a similar approach to dealing with Rex whom they hired to create the software for the virtual therapy. The manager tells him, “Alright, let’s get straight to the point. Everyone on the board loved your proposal! You nailed it, buddy!” However, he then adds, “But there’s a few aspects of your concept which won’t be feasible.” These comments sound positive, and Rex takes them that way, offering to adjust whatever he needs to. However, the manager continues, “Our internal IT team has been working on a possible concept for a similar project. And the final decision was that it would make more sense for us to have it done all together, in-house. Your whole idea was obviously way hotter and more innovative for sure, but we won’t be moving forward with it.” Thus, after months of working on this proposal, Rex is out with only eight percent of their original offer, as there was no contract, and Agileal has taken his idea and adapted it for themselves.

Franz begins with the superficial aspects of the company that are easy to mock, such as its being a shoe-free office where everyone wears bunny slippers or where they sit in ergonomic bean bag chairs, and shows the real problems. Rex’s real problem of not getting paid anything substantial for his work—his landlord repeatedly hounds him for the rent—leads to two other avenues for Rex and for Franz to satirize. Rex spends time delivering pizzas on a bicycle to try to earn enough money for rent, a representation of the gig economy so many people try to navigate. One night, Rex can see his future when he encounters an Uber driver who once believed such work would be temporary. That man began as a cab driver, but had to switch to Uber to make enough money to survive. He leaves Rex with some unhelpful advice, “Don’t take no crap from nobody!” The driver clearly takes crap from Uber, but Rex takes his advice seriously, so he shifts from such piece-meal work to making money by hacking.

Rex explores the dark web to find people who will pay him for taking on hacking jobs, and he uses a hack of Agileal to illustrate exactly how capable he is. Franz draws on the contemporary reality of companies that have to pay a ransom when they’re hacked and shows how they are often, on some level, deserving of those attacks. However, Rex is no idealogue, as he simply wants to make Agileal suffer for how they treated him. None of the characters, in fact, are what one could call healthy or well-balanced, turning the title of the book from self-help into satire. None of these characters, including the therapist paid to help them, are able to establish a balanced life or work or any combination, as Franz reminds the readers that we live in a society that makes such a balance challenging, even impossible, at times.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply