“An old sight, too, has its moment of birth,” writes Natan Altermann, one of the most well-known Hebrew poets of the 20th century, to open his poem Moon. It’s a pleasant notion, the idea that there is always room for a renewal in perspective, the implicit call to action placing in the hands of the reader not only the onus but its enabling power as well.

This moment of birth is what serves as the thesis statement at the heart of 20KM/H, the newest collection of short comics by Chinese cartoonist and web sensation Woshibai. The bulk of the cartoonist’s work takes advantage of social-media publishing, particularly popular globally on Instagram, which Woshibai employs as a length constraint, with his comics no longer than the ten two-panel pages allotted by Instagram’s image-per-post cap.

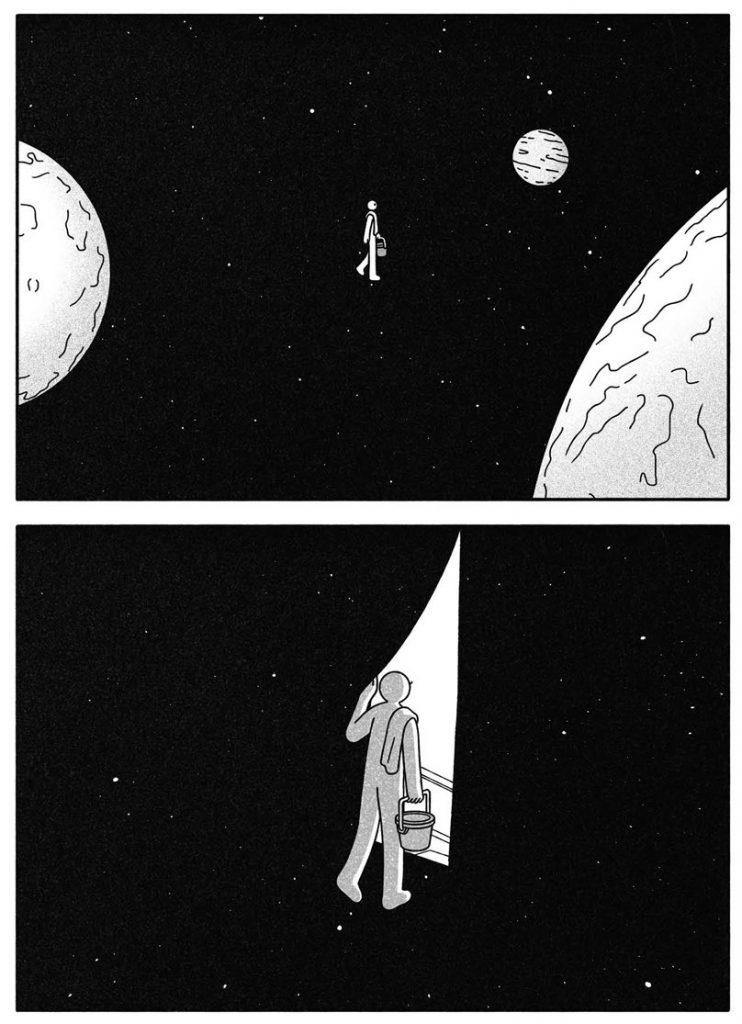

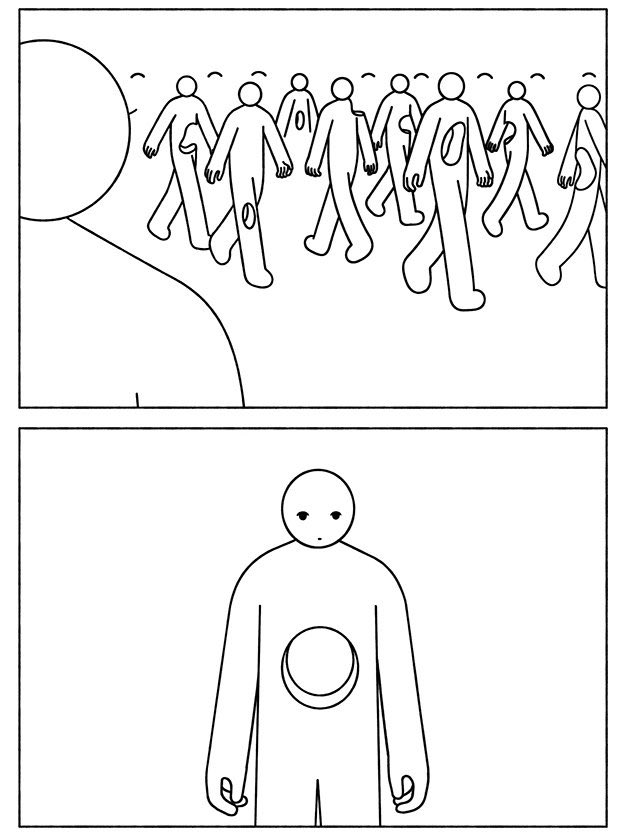

Woshibai’s cartooning can best be described as a blank, simplified cartoon-realism, which is to say an unvarying concreteness that, while not relying on photorealism or representationalism in rendering, still makes its laws of physics and dimensionality self-evident. His people, featureless beyond the broadest figures and facial descriptors, are recognizable as people from context, existing as semiotic cipher more than a proper human existence; their environments are depicted only insofar as they need to be, with the cartoonist frequently reserving his right to withhold detail where such is unnecessary. The work sports a utilitarian purity, rendered in a fairly thick uniform line, not varying in weight or quality. This internal dialect of shorthanded solidity is what affords the work the sense of established reality that the author takes great pleasure in subverting.

In part because of the brevity of his chosen format, Woshibai does not attempt to depict stories in the traditional narrative-structure sense. His comics have more to do with the motion and geometry of the world; there is a pure externality to his work, a physicality of engagement that does not preoccupy itself with the interiority of mundane life, instead only broaching ideas with the simplicity of raw image, allowing the idea to linger for but a moment before leaving the reader with whatever they could extol from it. Again I think of Yokoyama Yūichi’s mission statement, drawing people “as if they are being watched by insects or by animals or by the gods or by the room.” But, where Yokoyama deals in an externality of sensory overload, pulsing with sound and motion, 20KM/H takes the opposite approach, toning down sensory embellishment to a minimum.

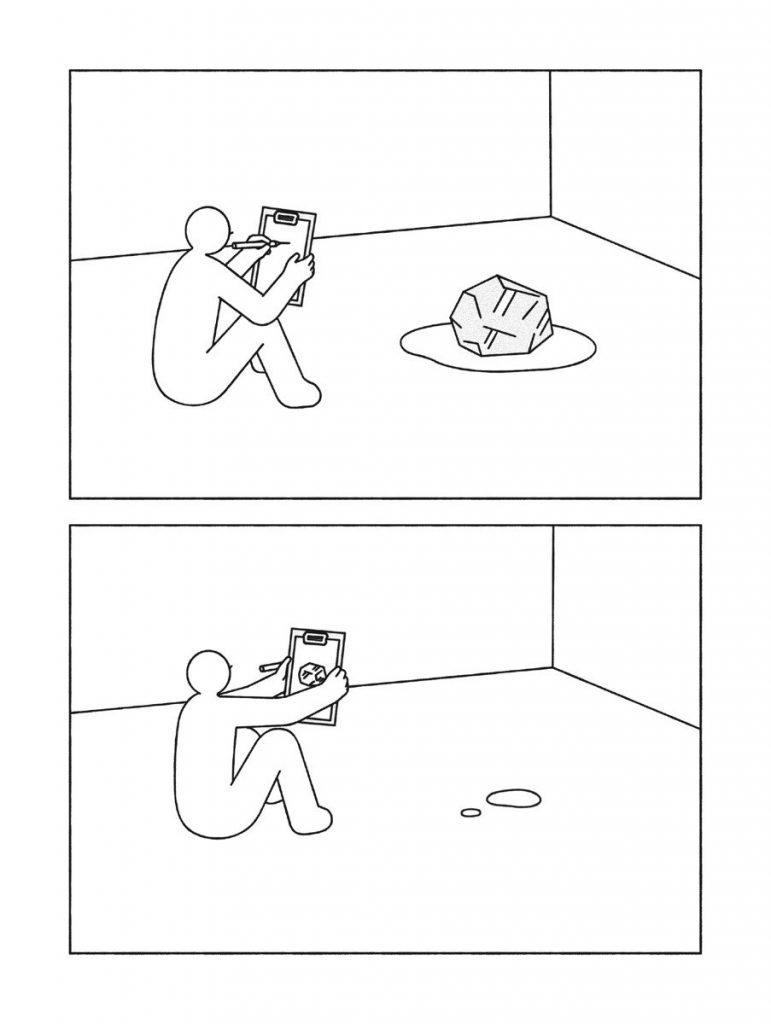

Woshibai takes great pleasure in reimagining, or otherwise deimagining (that is, entirely stripping away), the theretofore-ostensible function of the inanimate, through either manipulation of its geometry or plays on the relation between the geometry of the object and its function in progress. The first panel of Sleeping In, for example, shows a protagonist waking up in their bed, with the foot of the bed stretching past the panel border; the author uses the panel transition to shift angles, as in the second panel we see the bed from over the protagonist’s shoulder, as it stretches far past the edge of the panel. The rest of the story then follows the protagonist as they stand up on the bed and simply walk along it as it stretches out the house, through a forest, and over a canyon, ending at a different house where the protagonist promptly lies down and tucks themself in. It’s a cute visual pun, depicting the gradual “travel” from one sleep to another, which also subtly erases the existence of the bed—the object—as a narrow servant of function. In this way the cartoonist inverts the traditional perception of geometry as derived from its function; the geometry becomes either the dictator, not the dictatee, of function, or otherwise completely detached from it.

Other stories opt for a different approach, questioning not the what of the perceived function but the how. In Mirrors, for example, Woshibai’s protagonist walks alongside a long corridor of mirrors, examining each one as they go. Upon seeing a broken mirror, they look into its frame and find it transformed into a window into a completely dark room. Lined up behind the wall, at equal intervals (the intervals, of course, between each of the other mirrors), are the protagonist’s mirror images, looking at the empty space left: by virtue of the destruction of the barrier between it and its corresponding real, the reflection, the signifier, the decidedly-not-real becomes real in itself.

Where intrinsic function is not directly touched upon, the cartoonist often opts for a denial of the spatial relation between the protagonist (being the stand-in for the reader) and the object, casting doubt on the idea of physical fixity. In Woshibai’s stories, the two-dimensionality of comics renders spatiality arbitrary, calling into question the supposedly self-evident positioning of the external object; the cartoonist employs the treachery of composition-under-flatness to estrange the object out of its perceived scale. In Night Time the image of a moon hanging in the sky over a lake gets a literal etiology, as the author depicts the moon literally coming out of the rippling waters and suspending itself in the night sky; panning downward into the pond, we see its floor, crowded with many moons, not much bigger than the fish populating the water, awaiting their own evening-time. Another moon story, New Light, sees its protagonist stepping downstairs in a public building and happening upon a vending machine; sifting through their pockets and finding no loose change, the protagonist simply approaches the window and nips the moon out of its night sky, as small as a quarter between the protagonist’s thumb and forefinger. The cliché of the compositional reduction of distance under two-dimensionality, tantamount to a photo of tourists pretending to hold up the Leaning Tower of Pisa, is vitalized through tangibility, a cliché no longer.

This theme of decontextualization often carries into the narrative itself, and it is here that Woshibai finds the idea of art, particularly the printed book (being art as mass-object), to be a poignant vessel. Two of the stories put forth complementary narratives: in Petty Theft, a protagonist breaks into people’s houses in order to approach their bookshelves and tear one solitary page out of a single random book, only to return home and organize a multitude of stolen pages into a new book, binding it and tucking it into a tightly-shelved bookcase, filled, one can only assume, with similar non-books; Sorting, meanwhile, sees a different protagonist sifting through a newspaper and cutting up every single comma, finally pasting it into an album filled with commas and placing the album on a shelf alongside similar albums dedicated to other punctuation marks. The notion is, of course, absurd: both a random page in a book and a comma are rather meaningless on their own, imbued as they are with context only by their surroundings. And yet it suggests a compelling relation between part and whole, in which the part receives its new meaning by way of sheer chance and accident, surrounded by units it was in no way designed to be surrounded by.

This approach—this annihilation of the familiarity between object and subject, perceiver and perceived, user and used, as well as the mediating space between them—serves as fertile ground for the fascination with alienation that Woshibai shares with the aforementioned Yokoyama. Although the two cartoonists diverge in aesthetic approaches, Woshibai’s landscapes are innately antisocial (or at the very least asocial), hardly making mention of direct interpersonal interaction and often featuring only one human character. Indeed, social interaction is substituted for an interaction with one’s surroundings, typically in demonstration of the malleability—and erosion—of the perceived function of external reality and its self-expression via the inanimate; in a world where even the inanimate can hardly be trusted enough to be declared as known, it’s little wonder that the animate cannot even be touched upon.

At its grimmest, 20KM/H is a Sisyphead, finding no hope in its landscapes; in Void, the protagonist chops down a tree and builds a ladder into the sky, passing through the clouds in order to see an implied beyond, only to find nothing but the broken bits of the ladders of those that came before him. And yet, in the light of this despair, one finds a revitalization of one’s surroundings to be hope enough. The titular story of the collection sees a carriage, driven not by horse or donkey but by butterflies. The carriage slowly approaches the reader, then it drives away, unremarked upon. It’s not particularly fast, this carriage of butterflies, driving a mere twenty kilometers an hour. But, if you surrender yourself to its slowness, you may find beauty in it. Unknown, hard to articulate, certainly open-ended. A moment, perhaps, of birth.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply