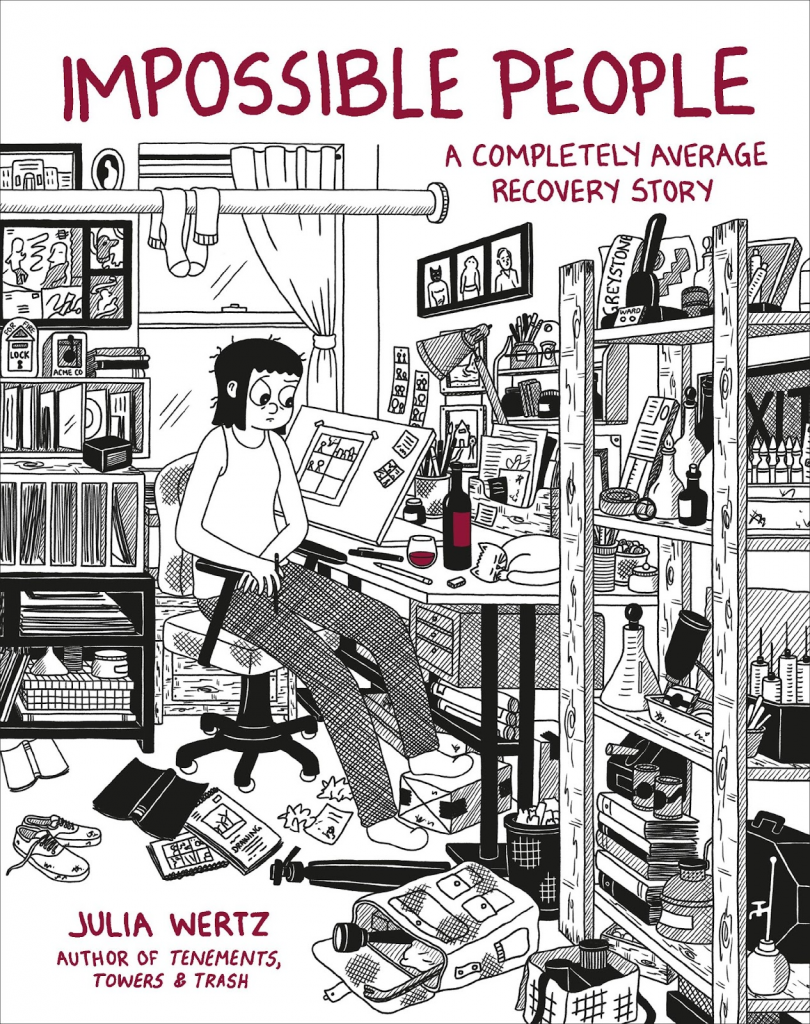

Much has changed for Julia Wertz since her Fart Party days, but there’s plenty in Impossible People, her latest book from Black Dog & Leventhal, that longtime readers will recognize. Wertz’s cartoon self still looks remarkably consistent, with her black, helmet-like hair and mismatched googly eyes. Her new comic, subtitled “A Completely Average Recovery Story,” also readily documents the mundane mayhem of her pretty ordinary life and packages it for our amusement, as usual.

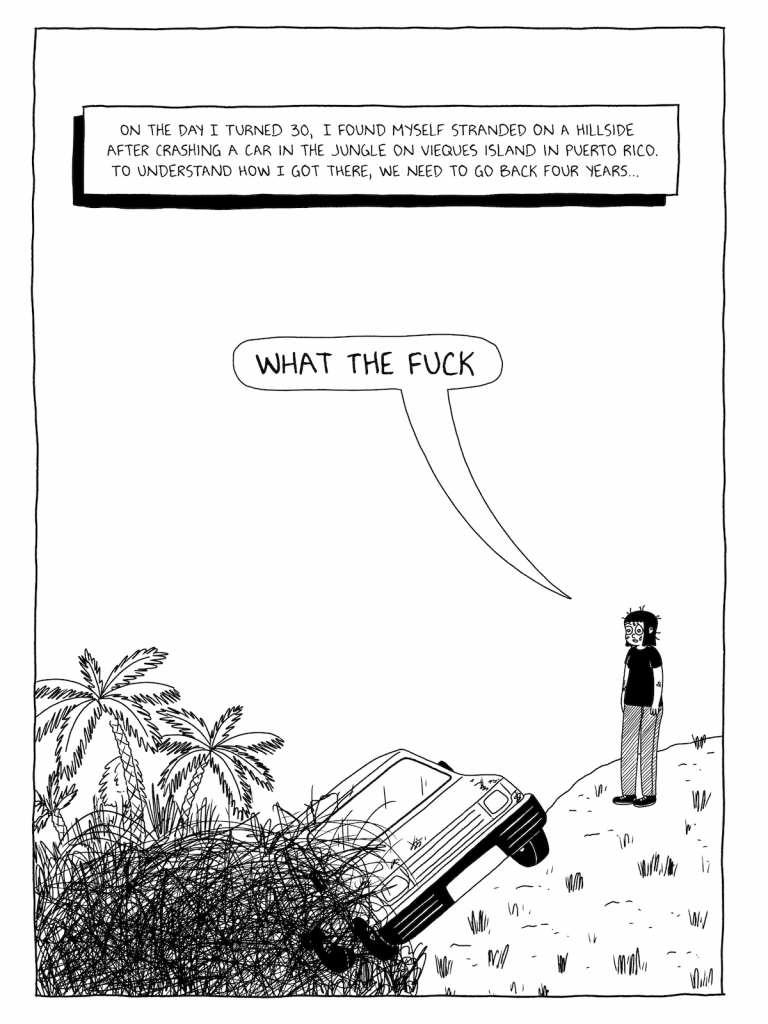

There are also structural similarities to her old work. The opening page of Impossible People closely parallels the first page of Drinking at the Movies, her first full-length graphic memoir; both confront the reader with a half-comedic, half-concerning birthday scene — turning twenty-five in a 24-hour Brooklyn laundromat where Wertz emerges from a drunken blackout (Drinking at the Movies), and turning thirty in a Puerto Rican jungle where Wertz crashes a rental car (Impossible People) — before immediately flashing back in time to tell the story of how she got there.

These continuities, though, are ultimately less striking than Wertz’s departures, from her old work and her old self. Impossible People, which chronicles Wertz’s arduous attempts to get sober during her late 20s, is about the despair of everyday life and the destructive consequences of trying to avoid that despair through substance abuse, and the book explores these themes with remarkable frankness.

Wertz has openly discussed her alcoholism before, of course. While booze is a reliable punchline in Drinking at the Movies, the book contains one memorable sequence in which Wertz draws her experience of drunken dysfunction as a literal battle with her own brain, which has a tendency to run away and get smashed without her. This approach, while arresting and effective, approaches her drinking problem by way of metaphor and self-deprecating humor.

Impossible People has jokes, and Wertz is still adept at depicting the ridiculous trivia of her life with “brilliant old-school comic strip timing,” as Jared Garner once put it. But she no longer feels the need to hide a discussion of genuinely serious problems beneath layers of irony.

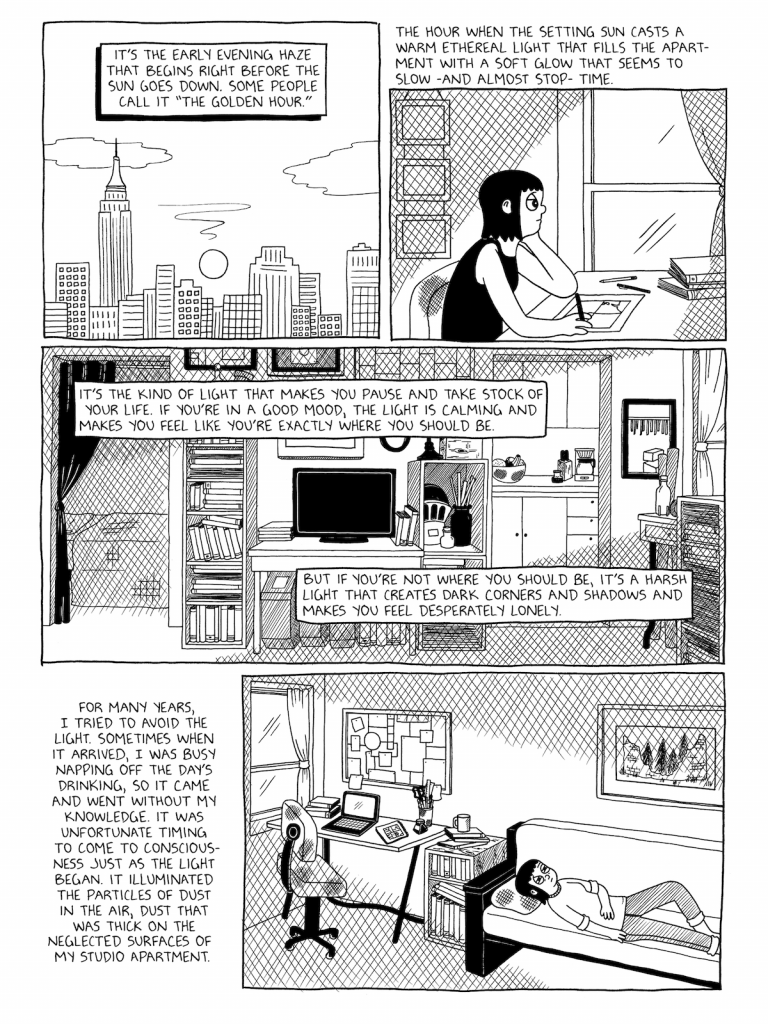

One of the book’s most powerful moments comes during a therapy session when Wertz describes what she and her friends call “the suicide light.” This is the “warm ethereal light” that suffuses her apartment right before sunset. It’s a description that sounds positive, but for Wertz, who is struggling with addiction and possibly clinical depression, the light is a barometer that tests her emotional stability. If she’s in a good place mentally, the light calms her; if not, the light conjures much darker thoughts.

Visually, Wertz represents the light as a negative space that interrupts a layer of cross-hatched shading. While her work is normally free of shadows — unless she draws herself literally sitting in the dark — the “suicide light” seems to summon this unusual pattern that closes in on Wertz’s figure from above and below, literally trapping her on the space of the page. It’s a place, as she puts it, that “was not where I wanted to be.”

The light represents a forced clarity that Wertz actively avoids, even as darkness closes in around her. Encountering it means reckoning with the reality that being a blackout drinker is actually shitty and miserable, not quirky and delightful, so she contorts her life to avoid it. “Most evenings, I drank enough to avoid facing how bad my drinking had gotten,” she writes.

It’s this kind of emotional vulnerability that makes Wertz’s new memoir such a decisive break with her past autobiographical comics (even the personal material about Wertz’s autoimmune disease that appears in The Infinite Wait). The book might be best understood as a sequel to a personal essay titled “The Fart Party’s Over” that Wertz wrote nearly a decade ago. In the piece, which also features earlier versions of panels and scenes that appear in Impossible People, Wertz describes the disjuncture so many professional comedians live with: The need to be funny in public while struggling with depression in private. The hidden misery of her alcoholism was, for Wertz, the source of her comedic talent and the fuel for The Fart Party. But it also led to a bifurcation of self, a split between her iconic cartoon persona and the reality of her existence. As she explains:

“The way I presented myself in comics was in a cartoony style, with short black hair and bug eyes. It was a style I’d settled on years ago, based on a hairstyle I had once, for about two weeks. I chose the style quickly, without much thought, but perhaps I subconsciously did it to separate my real self from my cartoon self. My cartoon self made my problems seem funny, but when I drew my real self in secret diary comics, the tone and style was completely different and much more reflective of the truth during that year.”

These diary comics, drawn in a loose and watery hand, are included in Impossible People, interrupting the narrative with glimpses of an unfamiliar face and scattered objects — books, wine bottles, the same sweater worn day-after-day. Wertz makes clear that she originally drew these pages as a private exercise to get past writer’s block, not as comics to be shared, which lends the images an even deeper sense of intimacy. They are a fragmentary panorama of quiet pain, not a story or joke designed for an audience.

We can argue about whether these vulnerable pages truly represent Wertz’s “real self,” but that discussion feels irrelevant to me. Treating any diary or memoir comics, no matter how private, as an unfiltered look into an artist’s life is a trap. The Fart Party was a representation of who Julia Wertz was, at one point in her life; those comics were one truth, but not the whole picture. Impossible People is hopeful, and not just because it shows Wertz climbing, slowly, out of her depression and addiction. It also proves an artist need not be trapped by their earlier work, even if that’s what their audience might expect and want.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply