The subtitle of Julia Wertz’s latest book effectively sums up the overall arc of the narrative, as it tells the story of her realization that she was an alcoholic, then covers the years in which she got sober. If there were such a thing as a “completely average” story, hers seems to be that. There are no terrible lows where she loses family members or jobs or significant amounts of money/possessions; there are also no amazing highs where she realizes how great her life is now that she’s gotten sober. Instead, she recounts a fairly steady progress, with a few moments where she slides back into drinking or, at one point, using pills. Of course, it is that seeming simplicity that hides so much more of what’s going on in this book.

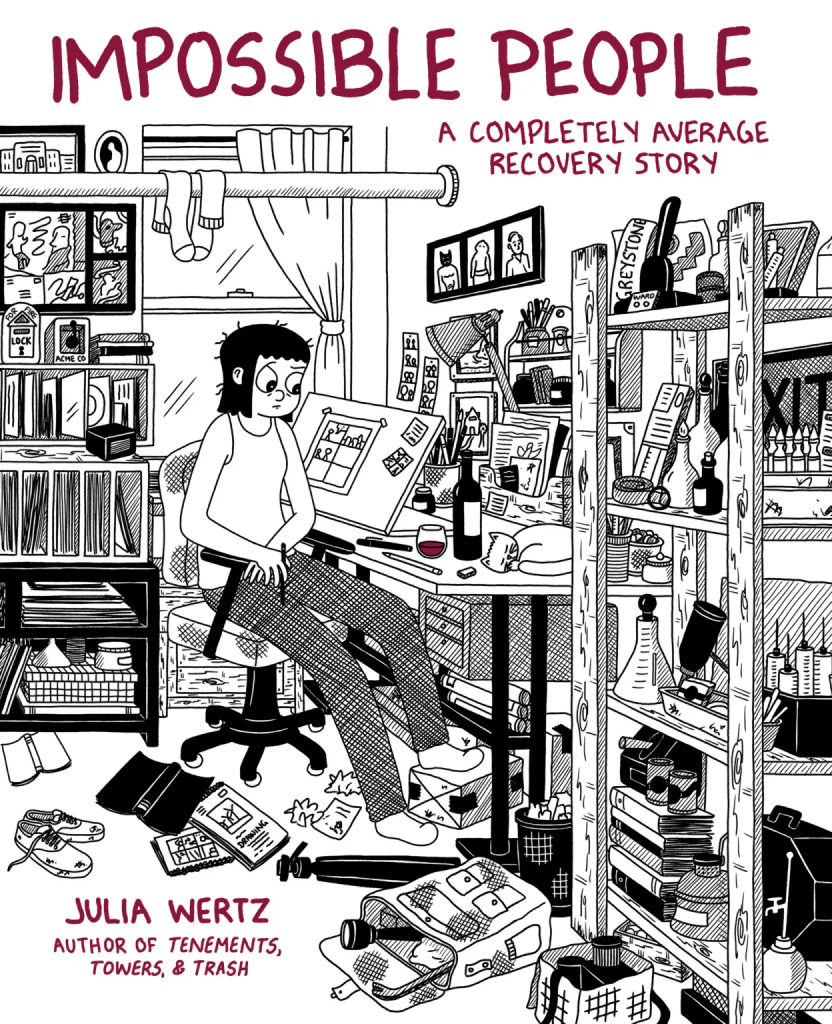

Similarly, Wertz’s artwork is superficially basic, but with much more going on in panels than readers first notice. She composes the entire book in a black-and-white palette, using lighter and darker shades of gray for the various lighting in abandoned buildings or when it’s dark in her apartment. However, the level of detail in some of the panels is almost overwhelming, especially when she walks the New York City streets—which is often—and when she’s in her apartment—also often. Both of those types of panels reveal Wertz’s intense focus on the details of her life, especially when she talks about the collecting she has done from abandoned buildings. When she’s interacting with others, though, the backgrounds often become less detailed, almost fading from view, as she’s focused on whoever she’s with, a theme that becomes more prominent in the book as it progresses.

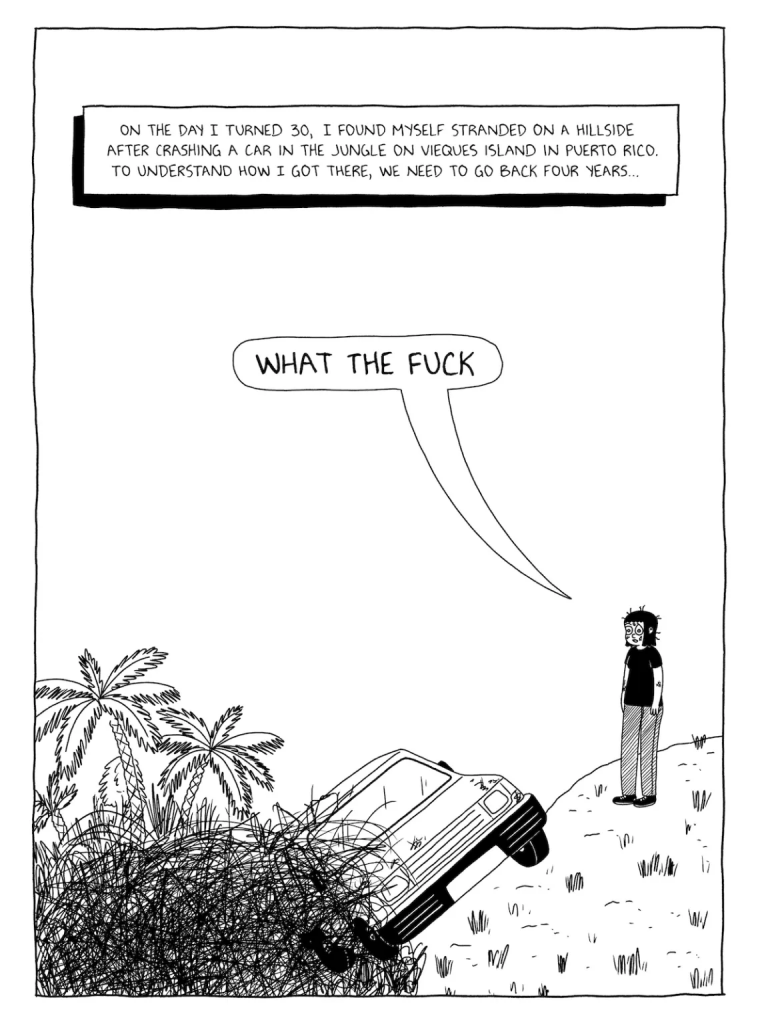

She opens her story with a flashback to when she is stranded in the jungle of Vieques Island in Puerto Rico after crashing a car. Given the focus of the book, Wertz sets the reader up to believe this event is the result of her drinking, but it’s not related to alcohol at all. Instead, it connects to a relationship that she was in at the time, a sub-theme throughout the book. Most of the book takes place from 2009 to the mid-2010s, the time when she was not only becoming sober but also dealing with her community moving away from New York, while she was also experiencing more and more professional success, even landing work at The New Yorker.

Both of those experiences directly connect to her sobriety, but not in the way readers might expect. Given that Wertz doesn’t provide a traditional recovery arc—person gets sober, then experiences success—she connects her themes in a more insightful way. One of the main ideas she takes away from her recovery from alcoholism is how dependent she is on other people during that time. In fact, her move from focusing on herself to focusing on others is one of the ways she truly begins to improve. As she writes, “It had taken me years to understand why having people in my life on a deeper level was the key to staying out of trouble. It wasn’t because it filled up my social calendar, but because it gave me accountability. Not just for my own actions, but also to show up for others. It was really quite simple.” Of course, it’s not that simple, as many of us struggle with showing up for others. Wertz is finally at a point, though, where she is ready to hear that idea and live it out.

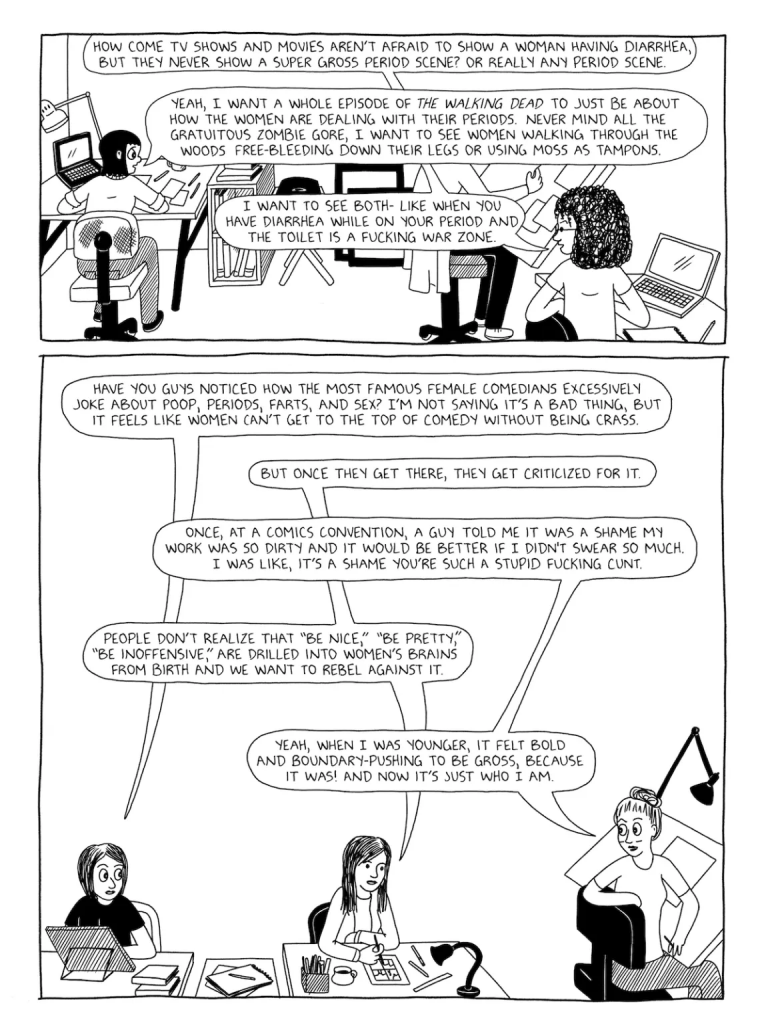

That idea shows up in her creative work, as well. Early in the work, she goes to work at Pizza Island, a shared cartooning space with women, such as Kate Beaton, Lisa Hannawalt, Karen Sneider, Domitille Collardey-Adebimpe, Sarah Glidden, and Meredith Gran. The book, in fact, reads like a who’s who of comics artists of her generation, given all of the conferences and readings she either attends during these years or thinks back on. In fact, it’s a meeting with Roz Chast that leads to her work at The New Yorker, which then propels her into other high-profile jobs. However, Wertz makes it clear that she gets to do what she wants for a living and get paid for it, while so many in creative endeavors don’t, and when so many people who do important work don’t get the pay or appreciation they deserve. She feels that way well before the supposedly-important publications began printing her work.

Lest any of her experiences sound dour or depressing, I should also point out that the book and Wertz are flat-out funny. Part of that humor is certainly self-deprecating, as is Wertz’s wont. For example, at one point, she is talking to her brother Josh, and she says that she is worried about boring people with her problems. She adds, “The last thing I want to do is be like a protagonist in a story who just keeps making the same idiotic mistakes over and over and at first the audience is sympathetic but eventually they’re just like ‘Oh my God, just fucking stop it!’ And then they hate her.” The next panel shows her holding the phone away from her ear looking directly at the reader with an expression of fear on her face. That comment comes roughly a third of the way through the book when, of course, she has been making the same mistakes again and again. Some of the humor, though, is simply observational humor during conversations with her friends or the situations she finds herself in, such as when she’s stranded in the jungle and ends up getting a signal for her cell phone by standing in the middle of the creek. So, when she calls her friend Jen, who asks, “Where are you?” her only response is, “Uh…never mind about that.” The situation isn’t humorous at the time (and it’s even worse than it sounds here for reasons I don’t want to spoil), but, of course, Wertz can later make jokes about it. She even admits that her earlier work (called The Fart Party) was her way of ignoring the hard parts of her life she didn’t want to deal with. In case fans of scatological humor are concerned, Wertz still has fart and poop jokes.

She’s now writing the book that does deal with the difficult parts of her life, though she still only alludes to some family background without going into detail. In fact, the title of the book shows that, even in the midst of her move to sobreity, she was thinking about writing this book. Her friend Jen is talking with her about why some people don’t get sober: “A lot of people fail to get sober because they don’t let people in, they don’t follow advice, they don’t seek real help. They just keep struggling alone. Change is impossible under those circumstances. The world is full of impossible people, don’t be another one of them.” Wertz thinks for a second, then admits she was thinking that Impossible People would be a good title for a book about this time in her life. Jen chastises her and says that they’re talking about her real life, not a book. Wertz responds, “I know, I know. I’m just goofin’.” The look on her face in the next panel lets the reader know that she is serious, as she’s always thinking about her art.

Wertz makes it clear throughout her book that, while the world may be full of impossible people, the people in her life are anything but impossible. They’re kind and forgiving and caring, and they help her be a better person, partly by allowing Wertz to help them, as well. She clearly loves her family, especially Josh, whom she talks to more than anybody, given that he has also gone through rehab and gotten sober. Her friends and family care about her, and she cares about them, which enables her to weather bad relationships, the years of getting sober, and anything else that comes her way, enabling her to produce great work like this book. If her story is completely average, then I wish that we all had such a story to tell.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply