Takako Shimura’s manga are about queer awakening. Her simple, warm cartooning is gentle and inviting, welcoming readers into stories of painful marginalized experiences that feel accepting and beautiful, granting her queer protaginists dignity without sanitizing their experiences. Wandering Son follows a journey of transgender self-discovery from the childhood of its protagonists onward, Sweet Blue Flowers begins with the blossoming of lesbian feelings among high school girls. Even Though We’re Adults is also about the realization of queerness, the painful, tender road to coming out, first to yourself and then to others. But unlike Shimura’s prior works in translation which have focused on adolescence, the women who must step out of their respective closets in Even Though We’re Adults are in their 30s.

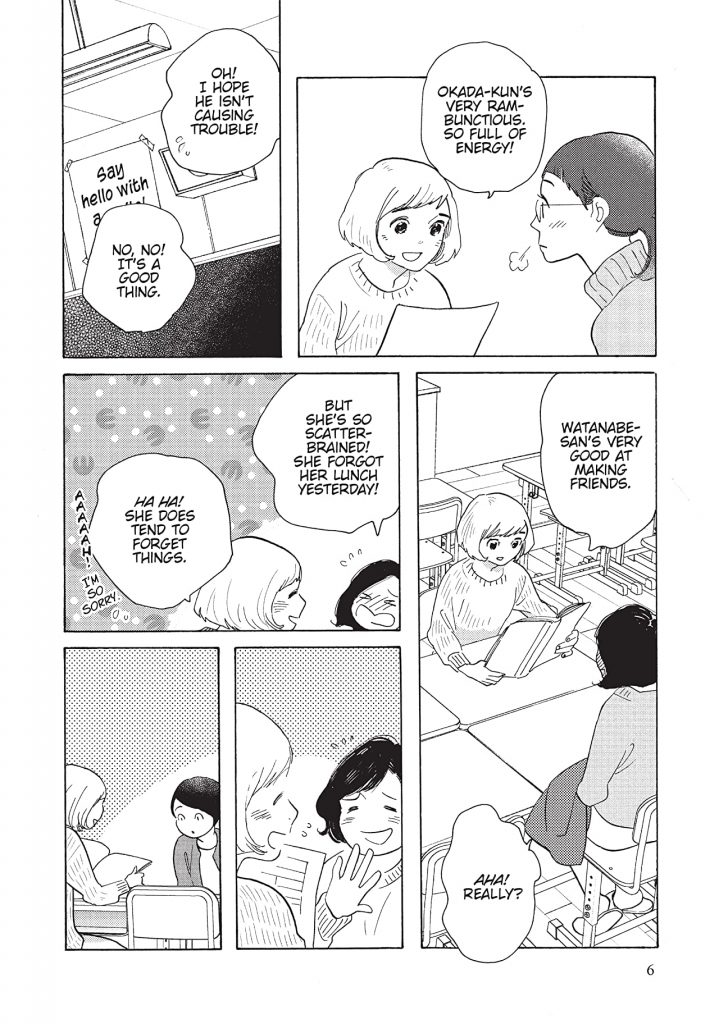

Even though We’re Adults brings together two queer women, one deeply repressed, the other jaded from years spent in the closet. Both are professionals settled into a stable life in feminized careers: Ayano is an elementary school teacher, Akari is a waitress. A chance encounter at a bar leads to a kiss and an exchange of phone numbers. They are connected, they like each other, they are both women, it is exhilarating. Something is beginning, but cannot be expressed. Ayano is married.

That brief moment of blissful mutual acceptance opens up a labyrinth of conflicts, Ayano confronted by her repression, Akari by distrust and resentment built up over years of grief and unfulfilled possibilities, both by the lives they built for themselves where their own happiness was never really part of the plan. Sapphism flies in the face of all their careful planning and preparation. Finding love creates the possibility that life might not be good enough without it. But Akari and Ayano are not the fetishized glamorous yuri manga protagonists who can throw it all away for each other, or simply live with a beautiful secret. Changing your life to accommodate a sexual awakening that brings you happiness is inconvenient and scary. The tension fueling the manga is as much “Will they or won’t they?” as it is “Will they both have the confidence to?” “Do they trust each other enough?” “Do they trust themselves?”

The question is never if Ayano will be able to keep her feelings for Akari a secret because she confesses them to her husband immediately. Not long after this she tells her parents as well. Her motivations are not bravery or proud self-acceptance, but fear and a desire to restore normalcy. “Coming out” is neither a resolution nor a climactic event; Ayano is unable to contain her secret lesbian attraction because she can’t bear the weight of a secret after a lifetime of oppression and acclimation to a stable heteronormal life. In repressing herself, she could ignore the deep discomfort of silencing herself. She wants everything to be fine, and, in turn, her husband and her family want everything to be fine as well. But they do not care about Ayano’s feelings — feelings that she, herself, doesn’t really have a grip on enough to understand as needs — they want to maintain a life and social construction that makes sense, that seems to be happy. Nobody in this comic is standing up to a recognizable, nameable homophobia. Ayano struggles to give herself permission to be happy and makes the mistake many of us make at the precipice of exiting the closet, asking for permission, and the people in her life who say they love her wield their authority as family to say “no.”

Akari is likewise stuck in a cycle of self-denial, jaded from years of quietly fizzling out relationships with bicurious women who tried her but did not try to love her. Atomized by her emotional labor and long hours as a bartender, Akari is committed to a life of mildly unhappy but stable anonymity. It infuriates her to be tempted to find happiness with yet another woman too scared to love another woman. Inconveniently, Ayano never quite seems to forget about her. Even as she pushes Akari away she always returns, timidly asking for just a little more time, too soon for her to leave her thoughts. Both women are accustomed to a life of denial, and their meeting brings with it the dawning painful realization that they cannot keep denying themselves anymore.

Even Though We’re Adults is a delicious melodrama that captures in its page-turning heart-wrenching moments the struggle to come out after a life spent not knowing. Not everyone realizes they are gay from a young age – many of us don’t know what those feelings mean or what they are, because there is nobody there to tell us. We feel it, and later we will remember how it was always who we were, but we don’t know until it becomes desperately, painfully necessary to reconcile. Ayano and Akari’s romance is like this – it begins at the moment they realize that they can be happy, that they can be lesbians, and becomes a drama when that possibility becomes something real, the pain of its absence becomes real, something they will have to struggle with themselves to maintain the urgency to fight for. I can’t wait to read the next volume. I want to know what happens next.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply