This month’s column is dedicated to Amity Jules Harper.

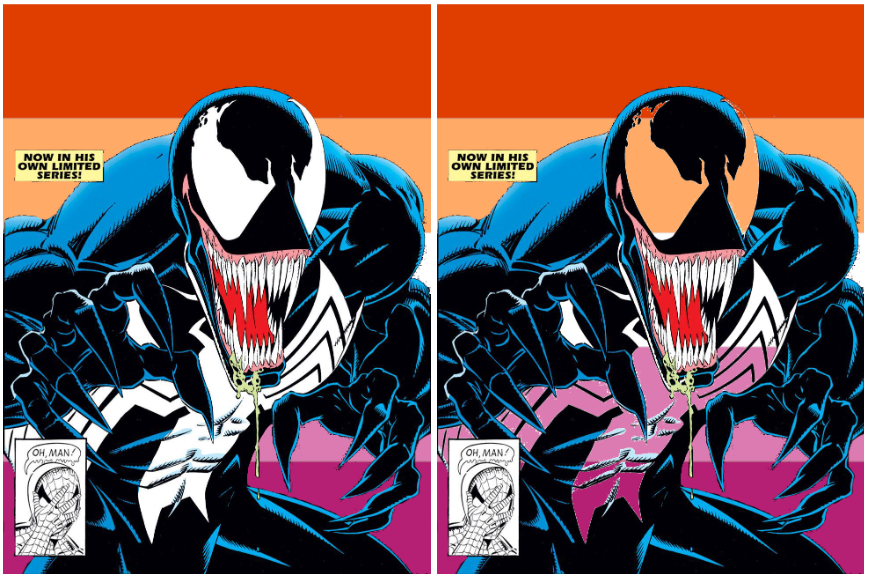

This month’s Comics Gridlock is all about queer yearning. Reading comics is not an inherently homoerotic activity, but if you want it to be, it can be. Case in point: the first superhero comic I ever read was Venom: Lethal Protector #1, and I suppose there’s nothing especially gay about that – although, like, come on, Eddie Brock literally has another man inside him. However, I happened to mention this to one of my girlfriends, and she squealed in delight and astonishment, because, as it turns out, this was also the first superhero comic she ever read. Somehow, it illuminated and deepened the true special nature of our sapphic bond. We were no longer just two girls who love each other, we were two girls who love each other and Venom: Lethal Protector #1!!!! Show me a horoscope that illustrates the romantic entanglement of souls as vividly as that. Comics aren’t just able to depict queerness – comics themselves can become the very stuff of queerness. And so, let’s look at some comics with gay and yearning vibes… and what vibe could be gayer than ROM Spaceknight?

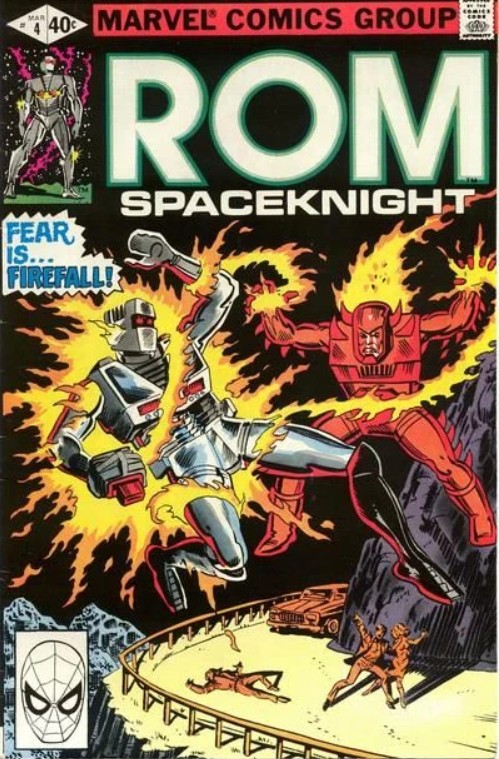

ROM SPACEKNIGHT #4, Bill Mantlo, Sal Buscema, Jim Novak and Ben Sean, Marvel Comics Group

ROM is one of those early 80s Marvel comics spoken about in hushed tones by a small-ish number of fanatics. It’s a sort of talisman of everything that makes that era of Marvel so juicy – a toy tie-in that can never be reprinted due to rights about a completely fucked cosmic battle awkwardly butting its way into Marvel’s New York, with the creative team of Bill Mantlo and Sal Buscema (and later the man himself Steve Ditko) cementing their legacy as Marvel’s vulgar auteurs. Our hero ROM is an alien from space eternally clad in cool powered armor, his eyes hidden behind the red glow of his sensors which peer out from the darkness of his helmet’s visor, a little tense, a little sorrowful. He has come to Earth to purge the wicked dire wraiths who have infested the human population, a task as devoid of joy as it is grand in heroism. Caged in the tragic chastity of his spaceknightly duties, ROM might be as explicitly fascist as pre-DKR superhero comics ever got, and also the most homoerotic, with their emphasis on personal denial and quiet longing in the face of a greater purpose, the beautiful, tragic-yet-glorious annihilation of the self – call it The Spaceknight Who Fell From Grace With The Cosmos.

ROM Spaceknight #4 opens amid an incredible aerial battle beyond earth’s atmosphere between ROM and Firefall, a human deluded by wraiths disguised as human scientists to believe that ROM is a cold-blooded killer of people, grafted to the armor of a fallen spaceknight which he believes to be a human weapon made to destroy ROM. While ROM’s human form is forever concealed behind his inhuman armor, Firefall’s human face is always displayed, shrieking with slashing lines of mad rage as hot as the flames boiling upon his suit, setting a perfectly Ditkovian visual binary of rational good and irrational anti-good action. ROM realizes he may have to break his code of never harming humans – or disgracing Spaceknight armor – to defend himself against his aggressor, and is tempted by rage as he realizes that the wraiths’ possession of the Firefall armor means they have slain the original Firefall – Karas, ROM’s comrade whose bond connected the two warriors “as surely as marriage links two lovers!!” Overtaken by mournful anger, ROM batters the new Firefall’s armor, crushing him into the earth’s surface, but finally stops before the sin of taking a human life. Indeed, the pain harbored within the suit, whether it be the agony of the dents inflicted by ROM’s punches or the grief of slain Karas’ lingering affection for ROM, is so overwhelming and haunting as to permanently cripple its deluded human dweller. He begins to feel the suit’s agony, amplified by the sensors which bind him to its powerful structure, he shrieks under the weight of the seething space metal: “TH-THE ARMOR!, IT WON’T COME OFF! I CAN’T GET IT OFF!” ROM stands tall, stoically, reflecting with remorse that his very soul will one day succumb to the meaningless violence of his holy war. ROM Spaceknight #4 is fundamentally a comic book about gay sex. It’s a great comic, let’s have more like this, 10/10

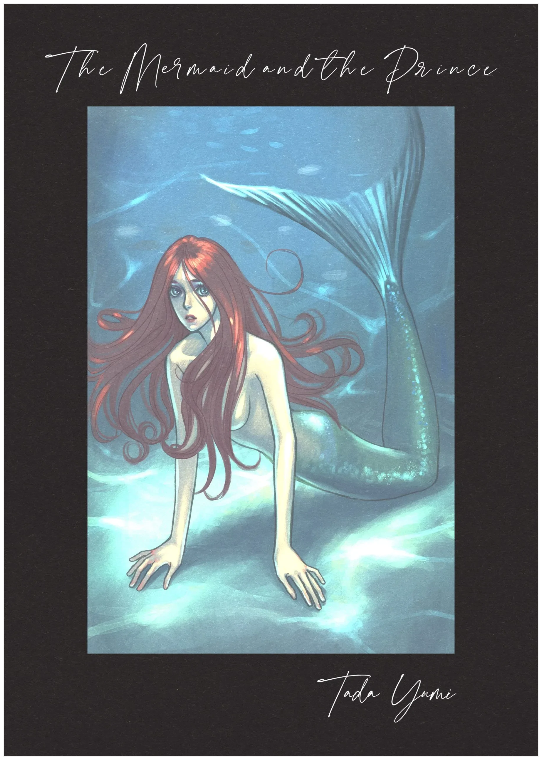

THE MERMAID AND THE PRINCE, Tada Yumi, translated by Anna Schnell, Glacier Bay Books

The Mermaid and the Prince is a cute little small-press manga about two hot people who are really sad and love each other. A prince, who is very hot and sad, is shipwrecked on an island before his wedding. He meets a mermaid who is also hot and sad and takes care of him because he is way too hot and sad to take care of himself. The two fall in love, but it’s doomed because the prince is betrothed to another and the mermaid is a mermaid. They get really sad about that and look pretty. Eventually, they figure it out and find a way to be hot and a bit less sad together. This probably reads like I think this comic is superficial or tacky, but it really isn’t. It zeros in on a really basic human desire – the desire for hot people to be sad and in love with each other – and explores that particular yearning lovingly and artfully, in vivid, tender color artwork. The book also includes a small gallery of illustrations by Tada Yumi of other hot people who look like they might be sad and/or in love. Definitely an artist to watch if you like hot sad people in love and/or really good comics.

EVEN THOUGH WE’RE ADULTS vol. 4, Takako Shimura, translated by Jocelyne Allen, Seven Seas Entertainment

I don’t have a lot to say that isn’t generally expressed in my review of the first two volumes, but I want to note that at this point Shimura is introducing a compelling parallel storyline to the main frustrated romance of the series, a social rivalry between three girls at the primary school Ayano teaches at. Two childhood friends, Yuka and Mana, become a small clique with a third new girl named Nitta, trading an exchange diary nightly. After Mana forgets to write in the diary for a few days, Mana and Nitta begin trading a new diary together in secret. Yuka becomes jealous and the friendship is broken up by rivalry and jealousy. Innocent, childish stuff, but the sapphic frustrations are there, and, as Ayano finds herself involved in managing the children’s conflict, one senses her awareness of the unspoken emotional turmoil and confusion brewing underneath this schoolyard drama. Quietly, she has to confront how she remembers the feelings these kids are expressing, how they’ve stayed with her in her mostly closeted adulthood, how she can’t really tell these girls about what they are going through, how much she can understand, any sort of real guidance, because it isn’t even permissible to say these things about herself in polite company. This is the sort of queer melancholy that sympathetic hets often neglect to imagine, the loneliness that is never really just your own but the loneliness in others that might not always be safe to name.

And as long as I’m writing about this manga again, I would like to note a recurrent theme in reviews of Even Though We’re Adults that really ought to be put to rest: noting that Ayano’s husband is sympathetic and well-intentioned. He’s not evil, to be sure, Shimura isn’t an artist who is going to demonize anyone in interpersonal dramas. The pressures and expectations he is placed under are explored with great sensitivity; his perspective is legible. However, his treatment of his wife is sexist and disgusting. Like many homophobes with intimate authority over a queer person, he begins from a place of alleged forgiveness and promises to his partner that she has room to “figure out” feelings that she’s finally claimed confidently enough to take the step of acting on. His patience negates her autonomy. He waits only for her to match his expectations. He refuses her wish to leave. Because of his apparently sympathetic struggle to understand that his wedded property is gay and human, he traps her. I think it’s wonderful how Shimura’s fiction provides space to appreciate his internal conflicts and motivations with empathy that is hard to afford for a man like him in daily life. The fact of the matter is, I’ve known many people like him, they are normal and they are frustrating. I think the desire to read him as kindhearted is wishful thinking on the part of heterosexual readers. Instead of applauding him as the goodest comphet sofboy, I would encourage readers to notice that his normalness and niceness doesn’t stop him from hurting his wife in a terrible way, and how many normal, nice people are capable of acting just as cruelly under the kyriarchy that all of us are subject to.

—

Okay, that’s enough for this month, I’m out. Next time… well, I dunno, my approach to this column is to write about what I want to write about at whatever point I read something that sparks a paragraph in me. But I would like to do something special for Halloween. I think that would be great! Until then, if you are someone who has the leisure to buy zines and/or imagine fictional superheroes kissing, you also have the time and/or money to materially support marginalized queer and trans people, even a little bit can mean the world to many of us. LOVE COMICS XO

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply