Takeshi Kitano’s sophomore directorial effort, Boiling Point, concerns a baseball team’s loyalty to their ex-yakuza coach. Incensed by an attack committed by the old gang, hapless Masaki and a friend decide to buy a gun in Okinawa, where they meet Kitano’s washed-up gangster, Uehara, in a karaoke bar. Uehara oozes danger and predation, and he wastes no time encroaching on one young man’s personal space. In great part, Kitano plays the role for uncomfortable laughs, a blackly comic atmosphere ramping up over the course of the film. However, there is an air of tragedy about Uehara, a suggestion of sadness, and a fascinating juxtaposition between Uehara’s violently aggressive sexuality and Masaki’s own airheaded, accidental attraction to a waiter.

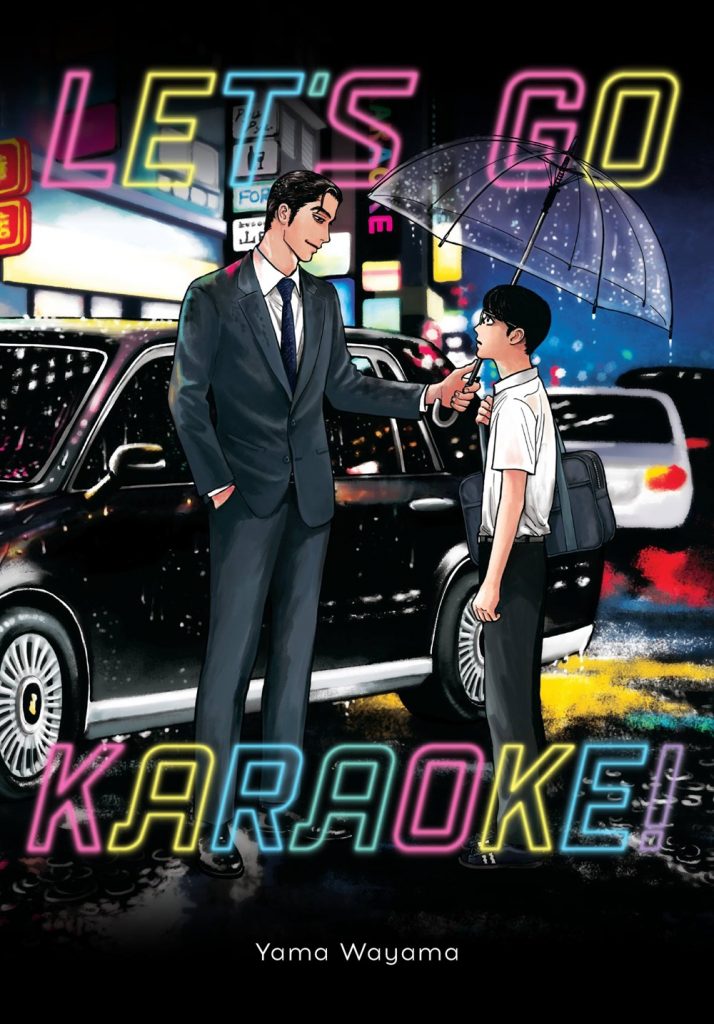

Kyouji Narita – the yakuza featured in Yama Wayama’s originally self-published manga Let’s Go Karaoke! – recalls Kitano’s gangster in circumstance, if not in action. Kyouji isolates a younger companion in a room at Karaoke Heaven, encouraging him to skip extra-curricular activities, and monopolizing his time away from family, friends, and school. Unlike Uehara, however, Kyouji poses no real threat to his fifteen-year-old friend. The nature of his work affords him an undeniable level of intimidation, but he never takes advantage of this where the teenage protagonist is concerned. Criminal activities he handles coolly, but, elsewhere, Kyouji softens, undeniably fond of the talented teenager he has pursued.

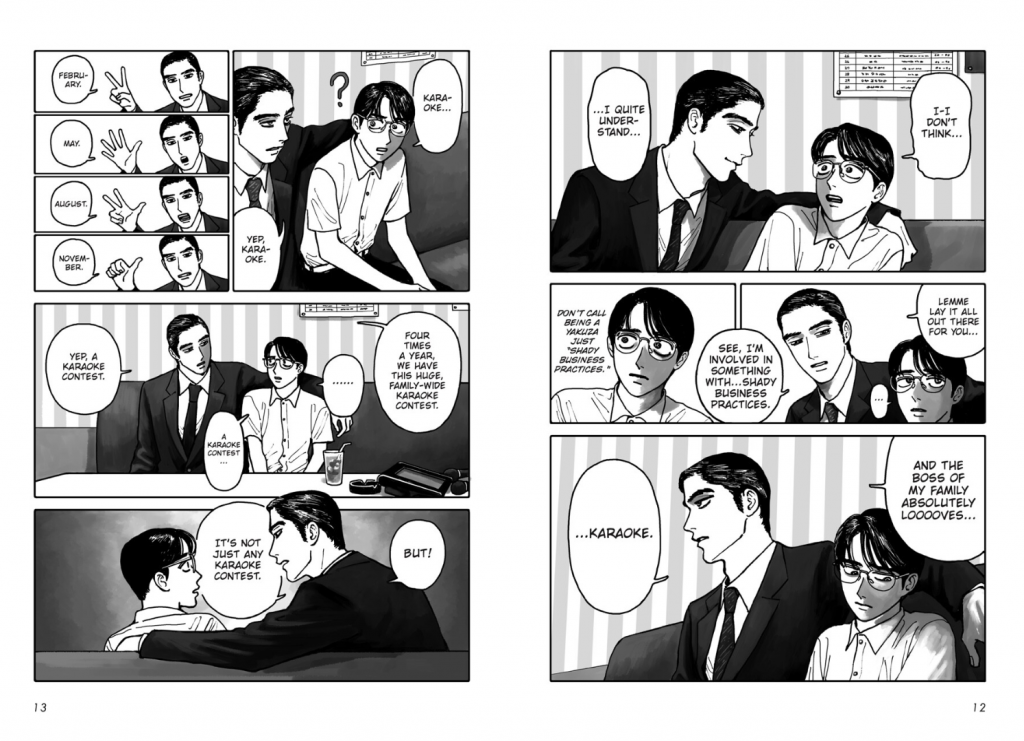

Star sopranist of his middle school choir, fifteen-year-old Satomi Oka dreads the inevitable: puberty. Already his teacher has lined up a younger vocalist should Satomi’s voice break before their summer festival performance. In the meantime, however, he faces a bigger problem. Kyouji Narita, fourth-generation assistant lieutenant of the Sairin family, has trawled middle school choir competitions searching for the most talented singer. He reveals that his boss loves karaoke, expecting all members to flex their vocal muscles in regular competition. The loser must sacrifice a patch of bare skin to the boss’ amateur tattoo skills. Intimidated but intrigued, and with no way of knowing how completely the agreement will change his life, Satomi decides to help.

Let’s Go Karaoke! presents a thoughtful portrait of a teenage boy cracking under self-imposed pressure. At the tender age of fifteen, Satomi begins to confront the loss of the one thing that drives him and that, in his view, gives him value. As a young achiever, he has experienced a high level of success in a short period of time, but no one has prepared him for the next step. He endeavors to nurse his rapidly weakening instrument. “It felt like my own voice was betraying me,” he writes. Alone, mulling over the appointment of a younger classmate as his backup, he recalls simply: “It hurt.” Twice weekly sessions with a yakuza add unnecessary stress, but it becomes clear that Satomi has found a new calling. Unconsciously, he transitions from singer to teacher. His critiques are accurate, if blunt, and he never hesitates. Still, his anxiety is palpable; sweat pours off him constantly, and he blushes and weeps at the drop of a hat.

This pressure to succeed crushes Satomi. In brief encounters with his family, we glean a warm, supportive home environment. At school, however, he has no close friends. He isolates himself from loving parents and affable classmates, subconsciously worsening the already unbearable pressure. Moreover, being involved with a professional criminal causes him to retreat further into himself. He worries for his personal safety (“I should apologize,” he thinks after an emotional outburst, “before he stabs me.”), as well as the safety of his family. Left unsaid is the way his parents might react if they knew that their fifteen-year-old son is spending time alone with a man twenty-five years his senior. Satomi’s problems are valid and varied, and Wayama presents them vividly. He is haunted one sleepless night by a horde of crying-laughing emojis: a reminder of a clumsy message from Kyouji. Satomi gives so much of himself – his talent, his knowledge, or simply his time – that paramount to his coming of age is the realization that he is allowed to ask for help, not only offer it.

Wayama’s depiction of this whirlwind of emotions ranges from reserved to righteous. Satomi is somewhat unpredictable. He appears delicate, almost waifish, and deliberately androgynous (Wayama casts him as her personal Mona Lisa). Kyouji dwarfs him in size and personality, but heavy smudges under his eyes imply stress and strain. Not only do criminal activities and the threat of an amateur tattooist’s needle weigh heavily on him, but this arrangement with Satomi invites personal reflection that we are not privy to. His behavior changes: cigarettes grabbed reflexively are stashed away, unsmoked, because he “shouldn’t send a middle school kid home smelling like smoke.” Practical decision-making comes naturally, whereas emotional intelligence needs practice. In one scene, he monologues obliviously to a silent Satomi before the teenager snaps. The outburst screams in huge black letters, his mouth a sketchy cavern. Kyouji handles such raw emotions poorly, but we gather a desire to understand.

It is impossible to ignore Kyouji’s interest in Satomi. His willful disregard for personal space blurs the line between intimidation and predation. He squeezes close to an awkward, blushing Satomi and, at times, can’t resist teasing and touching him. He is “adorable” to Kyouji, “like a liiitle puppy.” He is also, tellingly, “too damn nice.” Still, no lines are crossed. The attention can be read as innocent, even fraternal: the annoying older brother, pushing the younger’s buttons. However, a revelation in the manga’s bonus chapter concerning a twenty-year-old Kyouji and an older man suggests a deliberate testing of boundaries. It is hard to deny the pleasure he takes in provoking Satomi. Obvious, too, is the gradual shift in his approach. From the initial flagrant invasion of Satomi’s personal space to a peace offering of punnets of strawberries, we are invited to draw our own conclusions. Once Satomi’s work is done, Kyouji disappears. Is this an allusion to his true nature – cutting contact when he has no further use for Satomi – or a step taken to protect a schoolboy? Is it, perhaps, an act of self-preservation?

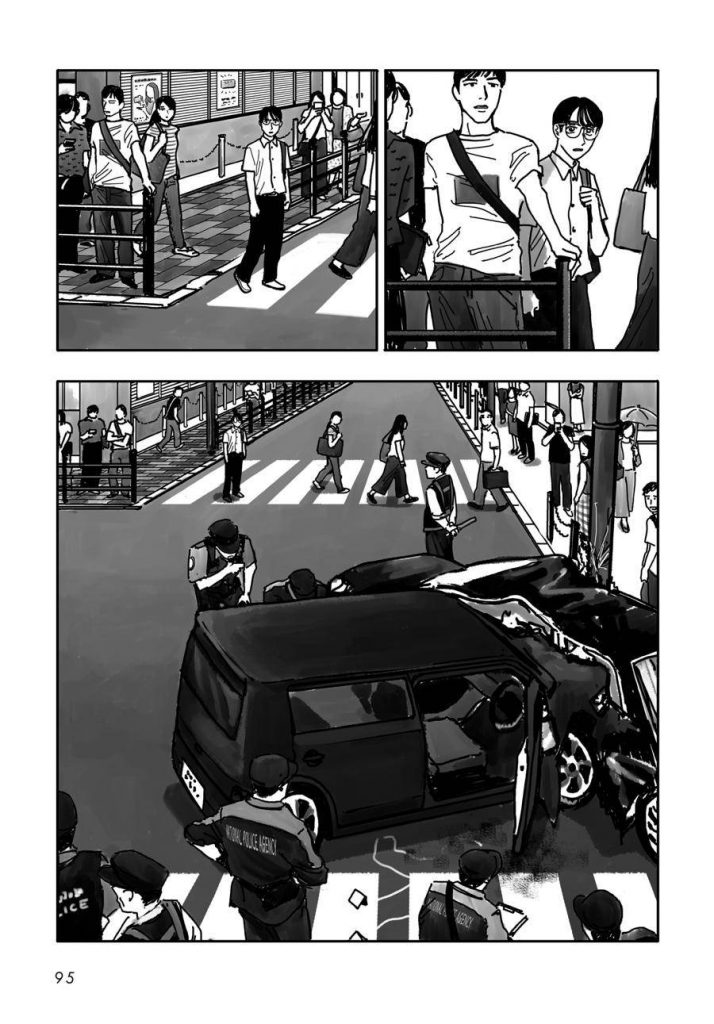

Together with this ambiguity goes the inherent silliness of the premise. It would fit well alongside Kousuke Oono’s The Way of the Househusband, which also concerns an incongruous, mean-faced yakuza. Wayama’s book is gently humorous throughout, playing on Satomi’s genuine fear shot through with adolescent bitterness, and Kyouji’s nonchalant underworld dealings set against his commitment to the singing lessons. During the first, Kyouji delivers a passionate rendition of X Japan’s ‘Crimson’ while a stone-faced Satomi orders a plate of fried rice before calmly and precisely tearing him to pieces. Later, Kyouji casually discards a severed finger and catches blood spatter in the palm of his hand. Kyouji’s detachment is obvious, his young friend’s horror all the more amusing in stark contrast. However, despite the humor, both realize the danger. At fifteen, Satomi is smart enough to know that he ought to keep his distance, but not quite sensible enough to stay away. Kyouji takes steps to protect his young companion, and Satomi (literally) clings to him. For once, he has purpose beyond the choir, and that is more than enough to overlook reasonable doubts.

Speaking in hindsight (the narrative forms his high school graduation essay), Satomi acknowledges the inherently predatory nature of Kyouji’s calculated approach. The yakuza’s initial appearance is in silhouette: a shadowy figure lurking at the back of an auditorium, incandescent eyes fixed on an adolescent boy. Once isolated in the private karaoke room, Kyouji introduces himself, passing his business card across the table and through the panels. Rules are being broken here: formal rules, societal rules, and, as Satomi comes to realize, the rules of his own existence. Kyouji, too, finds himself confronted by ethical questions and lines that even a professional criminal should not cross. Satomi’s painfully honest emotional outburst prompts an initially unsympathetic response, followed by a simple apology. Kyouji re-evaluates both his own and Satomi’s respective maturity, acknowledging the need to modify his behavior and examine his detachment from the situation. He is so far removed from his own adolescence that he has forgotten how acutely felt is every emotion, how every struggle – every failure – is paramount.

Yama Wayama crafts a thoughtful coming-of-age narrative from an inherently absurd premise. She couches the nature of the central relationship in layers of humor, suggestion, and plausible deniability. Indeed, many readers may not catch the undertones. Kyouji’s intensity can be read solely as a facet of his criminal lifestyle, Satomi’s confusion and distress aspects of his anxiety. Either way, Kyouji’s steady presence helps Satomi realize that his protective shell could stand to be broken. Where Boiling Point revels in its career criminal’s amorality, Let’s Go Karaoke! allows for a code of ethics. Uehara is an opportunist, spicing up an empty life with casual assault. Kyouji’s intimidating façade, cultivated out of necessity, hides a fiercely protective streak. He cares for Satomi, to the point that he understands when his own interests put the middle-schooler at risk. Three years later, reflecting on the experience for the first time, Satomi finds himself ill-equipped to understand it. “For some reason” a thoughtful gesture from Kyouji turns his brain “mushy.” This flimsy grasp on his own emotions heightens his suffering, compounded by the fear surrounding his murky future. For an intense few months, Satomi is the focal point of another’s life. Suddenly, the attention he never knew he craved is removed, and he is alone again, left to wonder what exactly happened.

Let’s Go Karaoke! began life in 2019 at the COMITTIA 129 doujin event. Yen Press’ 2022 release translates Kadokawa’s 2020 publication. Leighann Harvey’s English translation is mostly solid, though some phrasing is clumsy. Chiho Christie’s lettering fares similarly; Satomi’s emotional outbursts are beautifully rendered, as are the descriptors of his body language, but sound effects often remain unaltered. Yen has opted for the tried and tested method of providing an English equivalent onomatopoeia besides the Japanese original. This is no great problem, but the inconsistency is distracting. Still, the book itself looks lovely, with Yama Wayama’s cool yet intimate neon nightlife cover presented with a matte finish. The second of Wayama’s books to be published in English (the first, Captivated, By You, comprised stories of teenage outcasts), Let’s Go Karaoke! is a deceptively complex book, balancing silliness, warmth, and a hint of controversy.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply