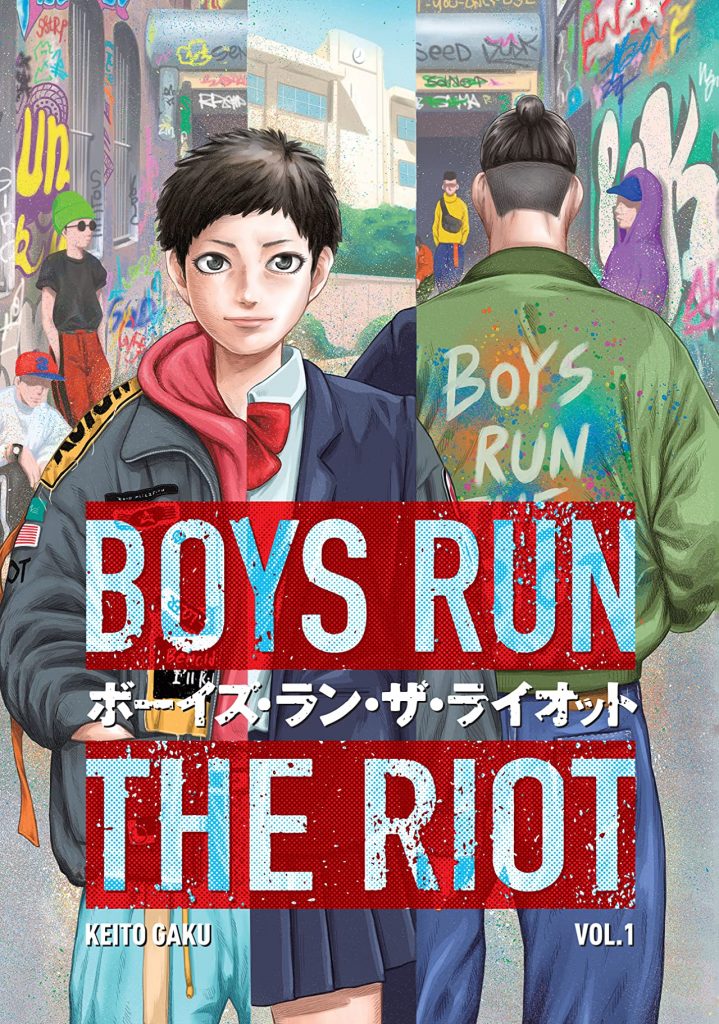

After winning the 77th Tetsuya Chiba prize for his debut one-shot Light, Keito Gaku took the core of that story and built it into the foundations of Boys Run the Riot. The manga follows Ryo Watari, a high school student struggling with secrets. Harboring a crush on a close friend is one thing, sneaking out to spray murals under cover of darkness another entirely; but hardest of all is making sure no one discovers Ryo’s true identity. Every morning on the way to school, Ryo slips out of the girl’s uniform and into a tracksuit. Chest bound and comfortably attired, Ryo can finally relax, but no matter the clothes or the situation, “I still can’t help but wish,” he thinks, “I’d been born a boy.” This struggle, and Ryo’s frustration with himself and the world around him, is at the heart of Boys Run the Riot.

In the first volume especially, Ryo’s frustration is palpable. A new student called Jin flagrantly breaks the dress code, waltzing into class wearing sunglasses and earrings. Ryo declares Jin “cringey”, but, in reality, it is Ryo’s desire to be himself that sparks this misdirected ire. Rattling around inside his head is the Japanese adage, “The nail that sticks up must be hammered down.” Rather than blame the society that wields the hammer, he experiences some level of envy towards those who have apparently avoided it. Ryo’s dysphoria is personal, but his shame and fear are direct results of a transphobic society: a society that has pushed him into blaming himself and other victims of oppression rather than the system itself. Luckily, he and Jin reach an understanding. Their shared love of fashion prompts Jin to invite Ryo to join his budding brand. When Ryo comes out to him, Jin immediately understands and accepts him. Together, they explore what fashion means to them, and how they can use Ryo’s talent as a graffiti artist to make their brand stand out.

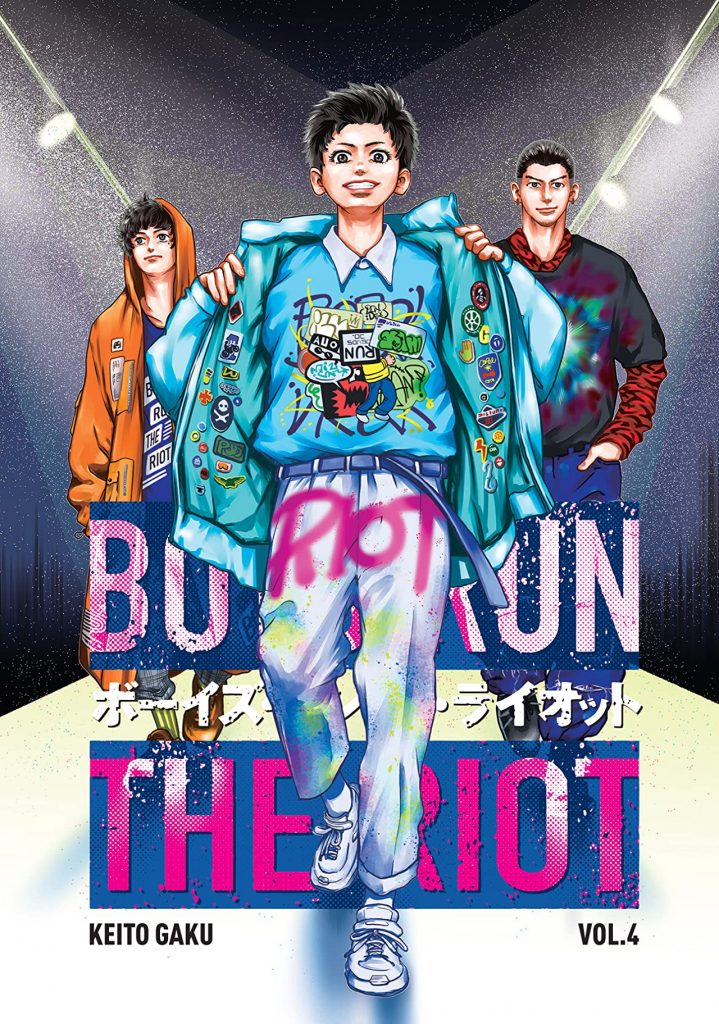

At the end of chapter one, Ryo creates a new mural (in reality created by artist Shinatro Wein) that depicts a young man emerging like a butterfly from the zippered back of a schoolgirl. Artistically, the image says everything that Ryo cannot yet verbally express, and it forms the basis of the brand. Through clothes, says Jin, you can “live as your true self.” His explanation helps Ryo realize that not only does he wear certain clothes to hide a body he hates, but also to explore something he loves. The boys agree that the brand should be more than a company; it should give people a voice. In the fourth and final volume, they settle on themes of rebellion, resistance, and empathy for the oppressed. A transphobic classmate accuses Jin of playing a “cheap trick”, and implies that having a trans designer is simply a gimmick. He is wrong, but another character – a genderqueer YouTuber named Tsubasa – thinks Ryo should use his identity as the brand’s unique selling point. Tsubasa also struggles with their identity and, like Ryo, experiences transphobia. However, their career advanced when they came out, so they believe Ryo should use his queerness to help the brand grow.

There is an interesting conflict towards the manga’s end between the brand’s message and its medium. A popular designer helps the boys take their next steps up the ladder, while admitting that his success comes from an appeal to the mainstream: nostalgia, familiarity, and pop culture imagery. The transgressive power of Ryo’s artwork is not translated to the brand’s designs. Volume four’s cover (designed in collaboration between Keito Gaku and Phil Balsman) promises a brash debut, but the reality is less exciting. Of course, Ryo and his friends are still young, just starting out in this competitive culture. Their desire to make a bold statement is stymied somewhat by their desire to start their careers. The designs are, therefore, simplistic and minimalist: the expectations for these young people grounded in reality, and reflecting an understanding that mass success comes from mass appeal. It is a shame that their righteous ideology is not represented in their catalog, but we can hope that, after the manga’s optimistic finale, the future for the boys and their brand is bright.

Boys Run the Riot’s explicit exploration of a trans teenager’s internal and external struggles sets it apart, but Keito Gaku also examines how fashion and art can offer an escape, and be an outlet for difficult emotions. Ryo uses graffiti to express things he cannot say and finds solace in clothes that fit his identity. Jin, meanwhile, yearns to escape his father’s oppressive expectations and to prove that he can live freely and independently. Another classmate, Itsuka, joins the brand as the resident photographer and experiences real friendship for the first time in his life. Jin and Ryo respect his talent and enjoy his company, something that Itsuka never knew he was missing. In the final volume, a student who appears briefly throughout the manga reveals an artistic talent that inspires Ryo to invite them into the fold and away from bullies. In each case, a young person finds a voice where they may otherwise have had none.

In order to find their voices and identities, the characters in Boys Run the Riot must take risks. Most notably, Ryo risks his safety every time he trusts someone with his identity. Coming out is not something a person does only once, and sharing that information is a risk every time. Ryo makes friends and allies at school, in part only after being forcibly outed by another queer person. Despite knowing Ryo is apprehensive, this person remembers how tough it was for them to be closeted and thinks that outing him will help Ryo find his voice and live freely. “Living feely also comes with sacrifices,” one classmate says, and sacrificing your safety is perhaps the greatest risk of all. Ryo’s bravery, and the tentative and incremental trust he puts in others, is compelling to follow. We realize that Ryo’s risks are building to the biggest risk of all: coming out to his family. Thanks to his friends’ support, and the strength he has found throughout the story, we have a level of hope; but we also know how much he stands to lose.

The aforementioned one-shot, Light, is included at the end of the fourth volume. The short is raw and rough around the edges, not least due to Gaku’s less refined artwork. The trans protagonist, Maki, is openly mocked, and the bullying he suffers is explicitly violent. Homophobic slurs are scrawled on his desk. A teacher tells him to “be more feminine”. Boys call him “insane” and claim that corrective rape can “fix” him. The bullying is so cruel and so specific, that Keito Gaku easily may have quoted his own bullies verbatim. Maki does find solace outside of school, in particular with his manager who knows he is trans and does not out him; but his internal life is the bigger focus here. After a group of boys attacks him, Maki floats naked in the river. “Maybe if I’m lucky, I can just dissolve,” he thinks. His ideation at that moment is implicitly suicidal, hinting at a dark conclusion. However, at the climax, Maki strips naked at school and sets fire to the girl’s uniform he so loathes. His defiant narration reads: “You think I’m crazy? You think I’m abnormal? Well, fuck normal.” Maki strives for liberation, not the assimilation expected of him. This defiance, and the striking transgressive image of a young person committing righteous arson, is missing from Gaku’s follow-up.

Boys Run the Riot sadly lacks the fire, both literally and figuratively, of its foundational one-shot. Maki’s struggle is visceral and raw, his pain acutely expressed through a bold narrative and unpolished artwork. Meanwhile, Ryo’s story fits neatly into the coming-out narrative so popular in trans stories. Additionally, Gaku’s artwork is so clean and refined that, at times, it feels unnatural, and it certainly lacks the raw vitality of the short. As a character, Ryo alternates between carving out his own identity and becoming a typical manga protagonist: an accidental pervert with a penchant for slapstick. There is strength in that. Having a trans protagonist step into a role and genre lousy with cis boys is a statement in itself. Gaku’s balancing act allows Ryo to tell his own story, pursue his dreams, and, perhaps, start a career, while acknowledging that his experience of the world will undoubtedly differ. Including Maki’s story at the end of the fourth volume – incandescent rage licking at the heels of an arguably sanitized tale – is a stroke of genius. The juxtaposition between Maki’s story and Ryo’s story parallels the boys’ desire to create transgressive fashion while understanding that greater success will come from an appeal to the mainstream.

The English-language release of Boys Run the Riot is a true labor of love, from the gorgeous presentation of every volume to Kondansha US’ all-trans localization team. The first volume includes an interview with the mangaka, where he discusses his experience growing up closeted, and his hope that the story will connect with and help other trans men and boys. Kodansha Comics editor Tiff Joshua TJ Ferentini’s acknowledgments express how “poignant” and “relatable” Ryo’s story was to read as a non-binary trans manga fan. Thanks to the manga’s exploration of fashion and art and the importance of taking risks, it cements itself as a powerful narrative even for those who may not share its protagonist’s specific identity. Keito Gaku is a powerful new voice in manga, and we can only hope that he will soon have more to say.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply