Much of My Life to Live, a one-shot comic that marks the first published work by Austin-based cartoonist Chloe, takes place in the cinema. This would have made it touching, for me at least, even under normal circumstances. Coming back to the story during the current global health crisis only strengthens its impact, from a closed fist to a falling anvil. After all, we can’t go to the cinema anymore. We can’t be in a closed place surrounded by people, as Alice described in this comic: “both together… and totally alone.” It’s such a joy, floating into a whole other world, sharing the same dreams with dozens and hundreds of strangers.

We can’t escape into the theater anymore (“escaping” has such a bad connotation to it, but as Tolkien noted once – the class of people most hostile to the idea of “escape” is called jailors). We can still see movies, but it’s not the same thing, not the same experience, no matter how big your home screen is, how good your sound system is, how stale and over-salted your popcorn is. You can’t just walk away from the rain, from your troubles, and sit with your eyes gazing up with all these strangers who are your brothers and sisters for the next 90 minutes plus. Alice, the protagonist in My Life to Live, is another such escapee: running away, from her partner-in-crime, from her former life. She runs into the cinema. She runs into being alone, together.

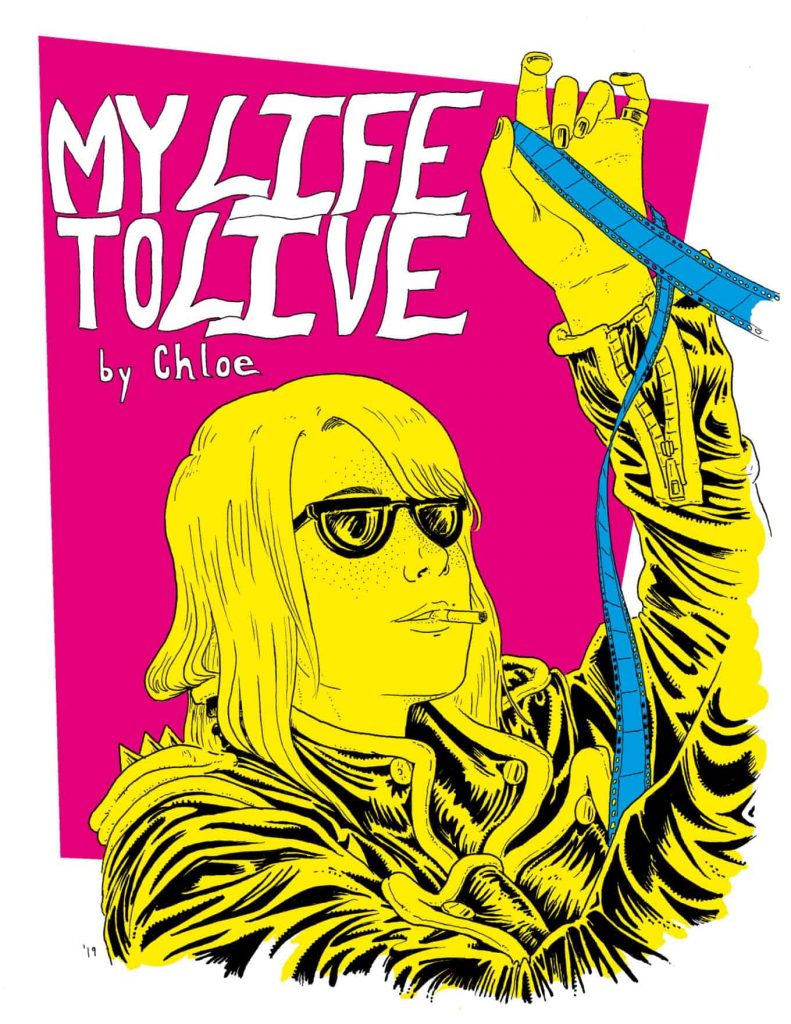

The first thing you notice about My Life to Live is the list of inspirations before the story begins, uniting such disparate talents as Wong Kar-Wai, Jean-Luc Godard, Sarah Horrocks, José Muñoz and others… Other than their sheer level of craft, what unites these various creators is how they often color life with a fantastic brush but never lose their touch with the stuff of life. They can take you into far away worlds while keeping your soul humane.

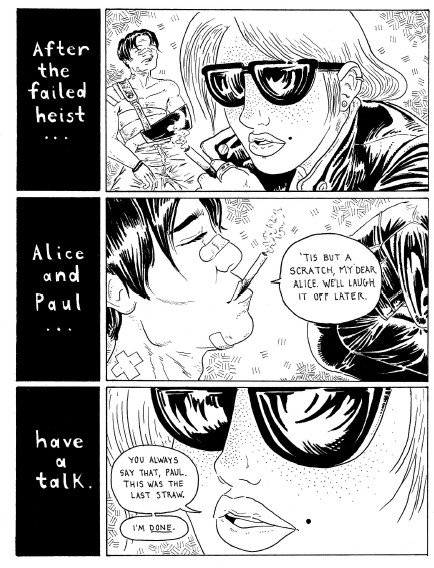

The second thing you notice about My Life to Live is how stylish it is. Everything in the book is slightly heightened, more beautiful and sadder at the same time. Alice and Paul aren’t just any dumb criminal couple, they are our very conception of the criminal romantic leads etched into the white page. They’re almost an archetype in how beautiful and doomed they are. When Paul takes the last puff from his cigarette in the first page, still recovering from his injuries, he looks like he just stepped off an Alain Delon feature. In the following page when Alice walks out on him, she’s the coolest thing on the planet. There’s a little boy looking at her, so astounded by what he sees that he drops his balloon.

This could be perceived as shallowness, as the comic telling how cool the character is instead of showing it; but Chloe’s art sells it – the effortless charm of the characters and the way they interact with the world. “Charm” is certainly an important aspect of the success of My Life to Live; every page of the comics is drowning in such passion for being. Alice smoking, Alice walking, Alice sitting there in front of the giant screen, breathing in the stale air, drinking deep of the life all around her. The comic loves her, and you end up loving her too.

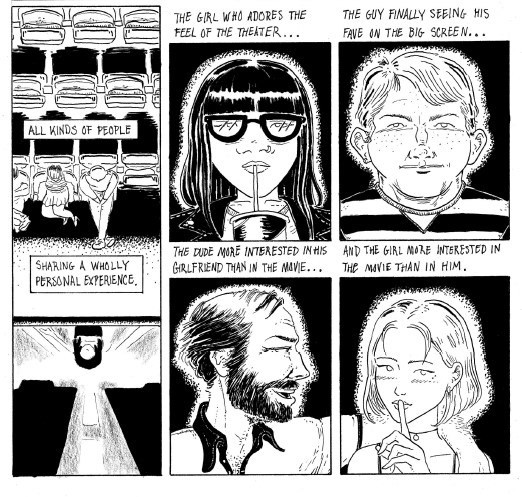

It’s not just Alice though, though she is at the center of the experience, it’s the people around her. That child mentioned earlier, the girl with the large glasses (“the girl who adores theater”), the boy with the determined face (“the guy finally seeing his fav on the big screen”)… they all have vitality to them, an essential quality of respect afforded to them by the text.

Rarely have I seen a work with such joie de vivre to it. Chloe’s line resonates as she draws faces and bodies, objects in space and cityscapes. An early scene mirrors Muñoz’s Alec Sinner work not just in the surface composition, that’s easy enough to ape, but in his understanding of the human spirit amongst the crowd; you are by yourself but you are not alone. Chloe’s art dwells deep into the souls of those depicted in a few simple strokes. I recall a character in Infinite Jest recoiling for the sheer intensity of Marlon Brando the first time they saw him on the screen: “in his quote careless way he actually really touched whatever he touched as if it were part of him. Of his own body. The world he only seemed to manhandle was for him sentient feeling…” I read that line and I think again of the scene of Alice touching the wall of the cinema, we don’t see her features but we see her slightly slouched shoulder, her face shadowed beneath her hairs, and we just know what she feels, we feel what she feels. She interacts with the world, and, through that interaction, she speaks with us.

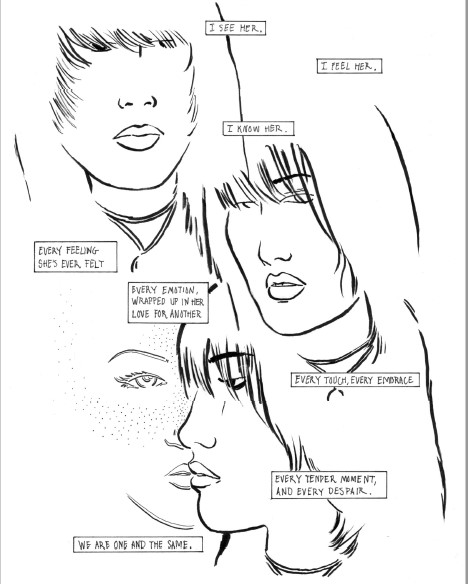

Then, halfway through the book, when we think we know where we stand with the story, My Life to Live pulls the rug under our feet. It’s a gentle pull, not meant to drop us on our knees but to shake us a bit out of our comfort zone. We are still in the world on cinema, we are just seeing things from a different angle, a wider one. We see Alice had become Claire, an actress, and is now watching herself on the screen as a fictional figure. Claire is looking at Alice, the readers are looking at Alice, seeing her on the screen as a fictional figure. She had seemingly become a subject rather than a protagonist. She’s now someone being watched, being directed.

“Movies are like a machine that generates empathy,” Roger Ebert once said. My Life to Live is exactly this kind of machine – something we need more and more in a world such as this.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply