When you feel adrift, go back to what you know, the sage advice goes — and on paper, that makes pretty good sense. Granted, it’s an inherently stifling way to approach life, particularly if your life revolves around creative pursuits, but it’s also inherently practical if you want to keep making a living. Ideally, I suppose, one would adhere to it and blow it off in equal proportion — pushing yourself to try something new, then refining the fresh set of skills that this step out of the nest requires before returning to the tried and true with a fresh set of eyes.

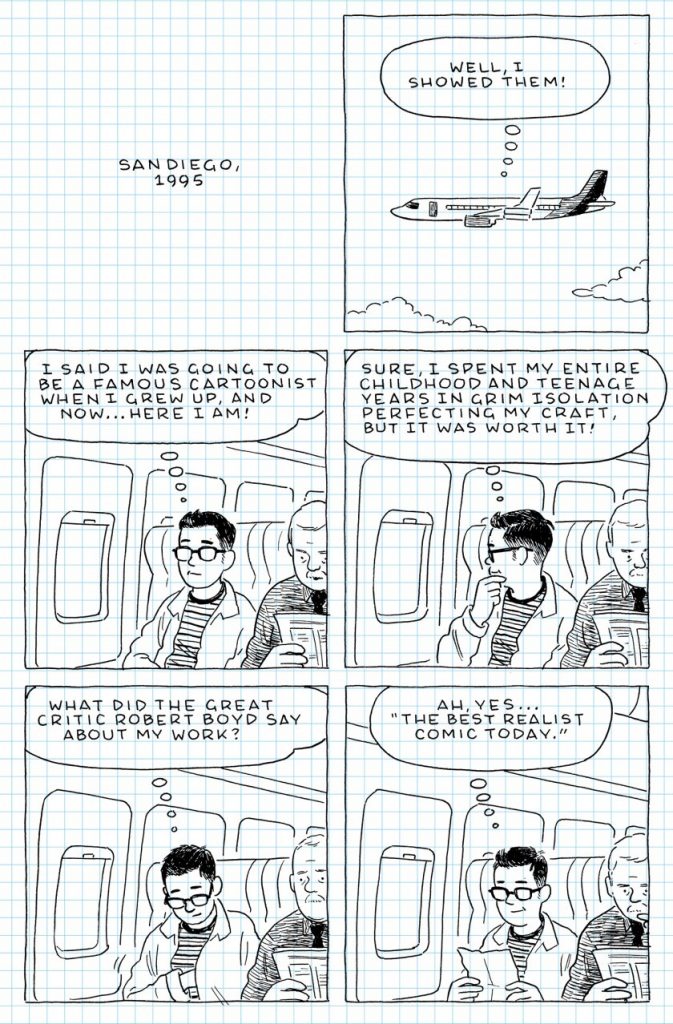

Certainly with his last collection, Killing & Dying, one-time cartooning phenom Adrian Tomine seemed well and truly adrift, adopting a stripped-down illustration style in service of “slice of life” stories that, more often than not, revolved around some kind of cheaply-arrived-at “twist” ending that frankly seemed beneath his talents. At heart, though, Tomine remained something of a deadpan humorist, albeit one who was determined to branch out in new directions both to relieve the tedium of doing the same kind of thing over and over, sure, but also for purposes of, pretentious as it no doubt sounds, growing as an artist.

That book’s tepid critical reception appears to have struck a chord, however, and so with his latest, The Loneliness Of The Long-Distance Cartoonist (Drawn+Quarterly, 2020), Tomine is back to the tried and true, even if his scope is more ambitious: a memoir of his entire artistic life, from childhood to present day, filtered through a lens of befuddlement and bewilderment. On the one hand, yeah, I get it — I’m roughly the same age as Tomine is, and when I look back at my own past it seems as though it really is, to dredge up and old cliche, another country. On the other, though, I have to actively question whether or not an exercise in navel-gazing is really what we need when the goddamn world’s on fire.

Granted, when Tomine — who is hardly what you’d call prolific at this stage of his career — started this project, he had no way of knowing a raging pandemic would necessitate an economic slowdown and its attendant social, psychological, and political miseries, nor that nearly nine minutes of a psychotic police officer with his knee in the neck of an unarmed black man would trigger a round of entirely-justified civil unrest and prompt a long-overdue accounting of this nation’s overtly racist past and present, but shit: it’s not like times weren’t plenty turbulent prior to all of that. We still had a would-be dictator in the White House, we still had rampant income inequality, we still had a corrupt and prejudiced legal system, we still had widespread environmental devastation on a global scale — you get the picture. Introversion is fine and dandy, absolutely, but it’s been a good decade or more since a project approached from a point of view this inherently privileged seemed in any way appropriate.

“But wait,” you may be saying to yourself, “Tomine clearly shows he was bullied as a child in this book. He’s socially awkward. He’s perpetually nervous and self-conscious. Where’s the ‘privilege’ in all that?” To which I respond “news flash — if you have the time and financial stability required to spend a few years doing nothing but writing and drawing a series of vignettes illustrating those very character attributes, you’re in a hell of a lot more comfortable place than anybody who’s actually gotta go out and hustle for a living.” So, yeah, this is a work that’s entirely dependent upon a certain amount of privilege for its very existence.

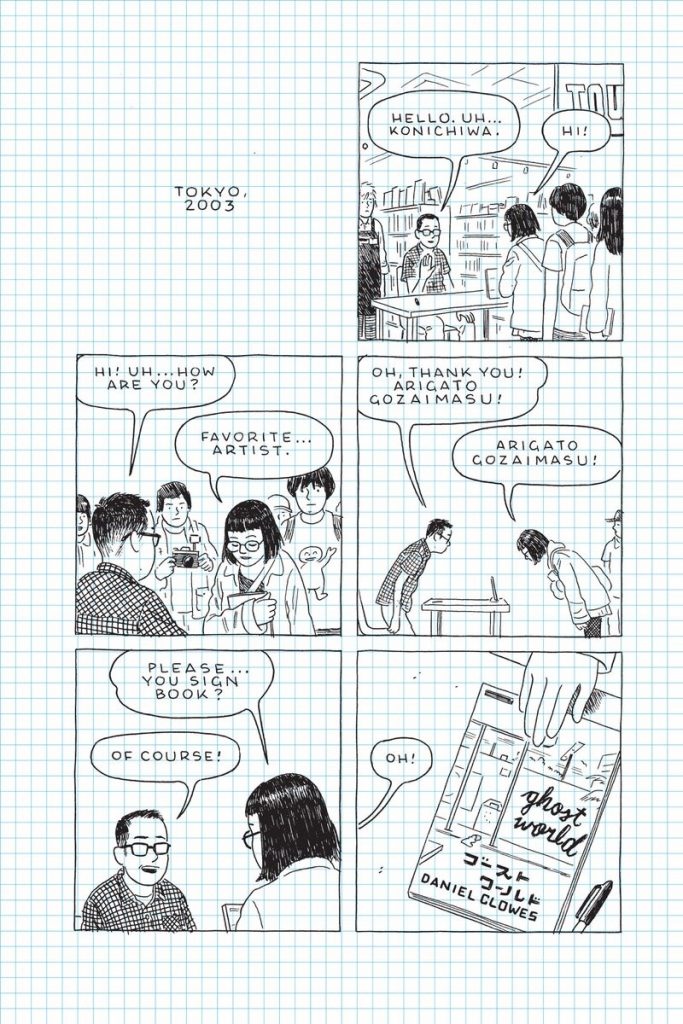

That being said, there are still points at which I feel privileged as a reader for the insights Tomine offers. They’re not as frequent as they used to be, but when he’s on, as they say, he’s on — and in The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist, he’s mostly on when he’s looking back at the early years of his career when he was a critical darling and very much in a creative “groove.” There’s plenty of “inside baseball” going on that only long-time comics readers are likely to appreciate, but the fact that Tomine still feels stung, all these years later, by an early negative review and by Frank Miller not even trying to pronounce his name correctly at an Eisner Awards ceremony at least goes to show that stardom (even small-scene stardom) hasn’t gone to Tomine’s head and that he’s not afraid to show himself as being petty and insecure. In other words, as with most of the best memoirists out there, he’s in no way looking to sugar-coat his own shortcomings, which is all well and good.

Unfortunately, much of the rest of the book isn’t. I applaud Tomine for getting back in touch with his humor roots, certainly — and definitely appreciate the fact that he’s putting forth the effort to do full-figure drawing again — but, by and large, we don’t come out the other end with any greater understanding of who he is as a person than we have by about page 20, and too often the fine line that separates self-deprecation and an obvious play for the sympathy of the readership is crossed here. We get it, Adrian, you’re a little neurotic — now tell us something we don’t know and that might give us some genuine insight into what makes you tick rather than trying to convince us this whole cartooning thing is a touch racket and that balancing creative concerns with commercial ones is such a dreary imposition on the life of an artist.

And then, finally, there is the “cleverness” — the last trick up the sleeve employed by those without a ton to say who are still desperate to convince audiences that they do. Sure, the fact that the book apes the format of an actual journal is thematically apropos and fun to look at, but when you pair it with an obvious and cloying title and an authorial viewpoint best summed up as “the general public will never understand how hard this is unless I show them,” well — the end result comes off as calculated marketing dispatched in service of covering up creative bankruptcy. We know Tomine is better than this, though, because he’s done better than this — and, while he seems torn between being embarrassed at his notoriety and still bummed that his previous work hasn’t received what he considers to be its due accolades, there’s little herein to suggest that he’s used either the “fame” he achieved or been deprived of as motivation to elevate his craft. He seems to feel that he’s had quite the journey one way or the other, and I suppose that he has, but, rather than coming full circle, with The Loneliness Of The Long-Distance Cartoonist he’s returned to the well only to find that it’s mostly dry.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply