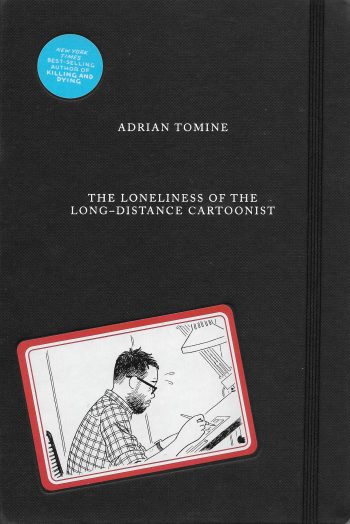

Today, I am following behind our lead critic Ryan Carey and his review of The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist. Ryan has written an incisive review of the comic, and I invite readers to check it out as well. Published in July by Drawn and Quarterly, The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist is a collection of autobiographical vignettes detailing some of the most cringe-worthy moments in Tomine’s career as a cartoonist, constructed in the form of a Moleskine diary complete with blue-grid paper and an elastic band. Ryan’s review is sharp, almost deadly, and it focuses on the “why” of Tomine’s latest work, specifically focusing on the questions, “Why this project, and why now?” He digs into Tomine’s other recent books and history as a cartoonist and illustrator and ultimately finds that Tomine has come up lacking.

For my part, I’m not as interested in talking about the why; Ryan has done a bang-up job and I don’t care to put myself behind that particular eightball. Rather, I want to talk about the what of The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist; more specifically, the way that Tomine tells the story of his life in the corners of panels, and how The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist, while based on “true stories,” ultimately feels like a closed-off narrative of the life of one of alt-comics’ most celebrated creators.

The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist begins its relationship with readers with an immediate reference to another work — Alan Sillitoe’s short story “The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner,” a story that was published in 1959 and adapted into a film of the same name in 1962. The film has long been considered a classic of British New Wave cinema and features a working-class boy who finds solace in long-distance running and uses his talents to defy the administrators of the borstal he is confined to after being convicted of robbing a bakery. The main character, Smith, starts the movie by explaining his situation:

“…It’s hard to understand. All I know is that you’ve got to run. Run without knowing why, through fields and woods, and the winning post is no end, even though balmy crowds might be cheering themselves daft. That’s what the loneliness of the long-distance runner feels like.”

The power of individualism against hierarchical systems and the goal to demolish these systems, despite personal consequence, is a theme that Stillitoe’s work often revolves around. This ideological framing is similar to that which Tomine uses for The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist. Tomine is the working-class artist, lost in the work of cartooning, drawing despite not knowing why, pursuing his art. The hierarchies he fights against are his bullies, his contemporaries, his critics, and perhaps even comics itself.

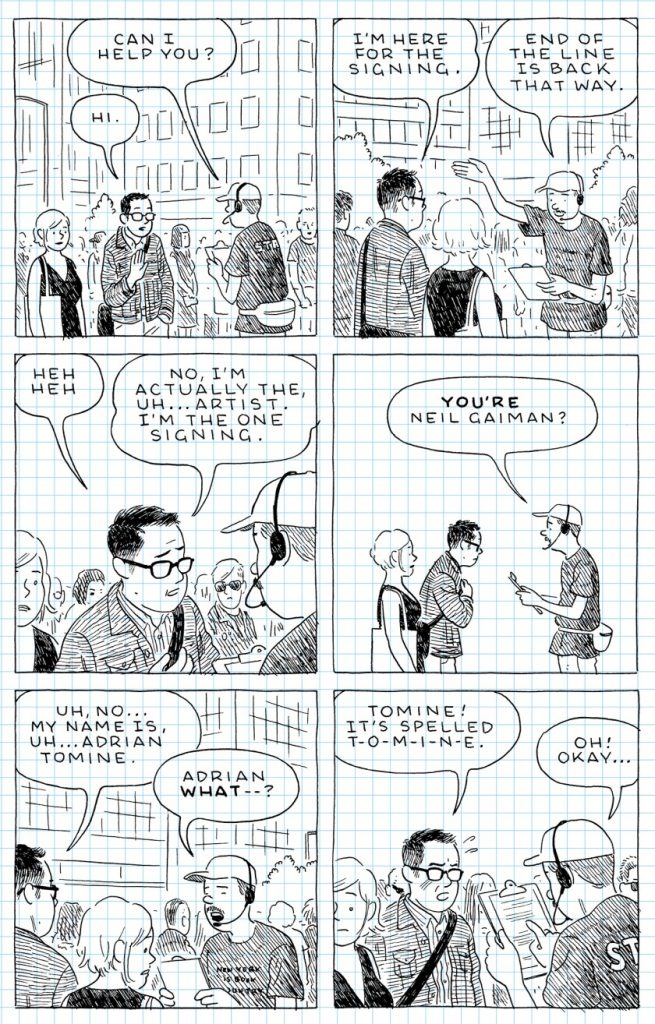

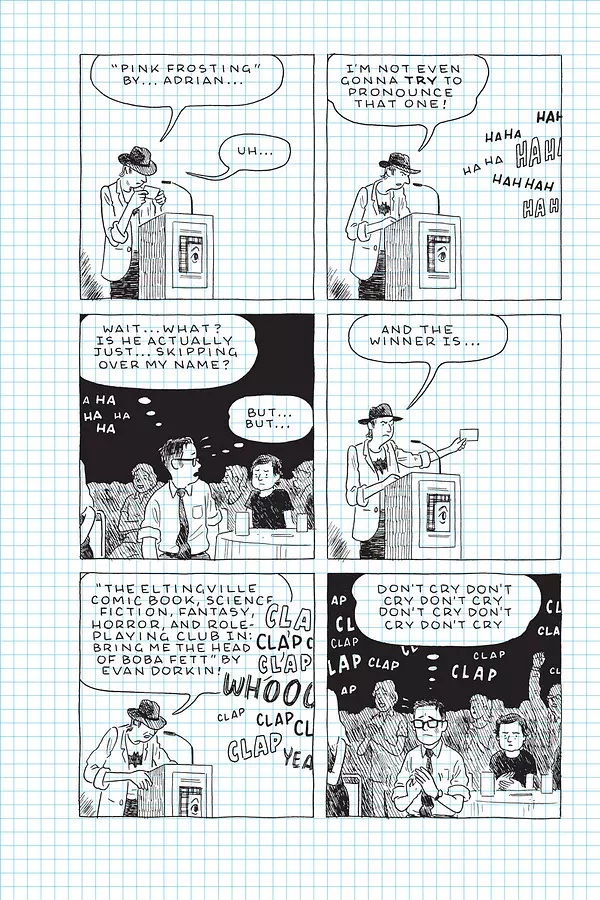

Tomine, by all accounts, has had a career worth celebrating, and he isn’t done yet. There’s been a general evolution to his work; a rocket of stardom through his alternative comics series Optic Nerve that he has parlayed into many successful books and a career in illustration that has also reached a pinnacle (award-winning illustrations on New Yorker magazine covers, among others). His work has been nominated for multiple Eisner awards, Ignatz Awards, the prestigious Angouleme Fauve d’Or, and his comic “Killing and Dying” won the 2016 Eisner for Best Short Story. But in The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist, these awards and nominations are set dressing. They are the things that happen between all of the various disappointments offered by a life working as an illustrator and cartoonist. Each of the stories in The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist plays to this idea of disappointments. An interview with prospects for a date ends up with a massive bout of diarrhea associated with lactose intolerance. The big line for his book signing ends up being for someone else. He is mostly ignored as a special guest on a comics cruise while people at his dinner table crane their necks to hear the words of Neil Gaiman. To Tomine, bad things are the only things worth remembering.

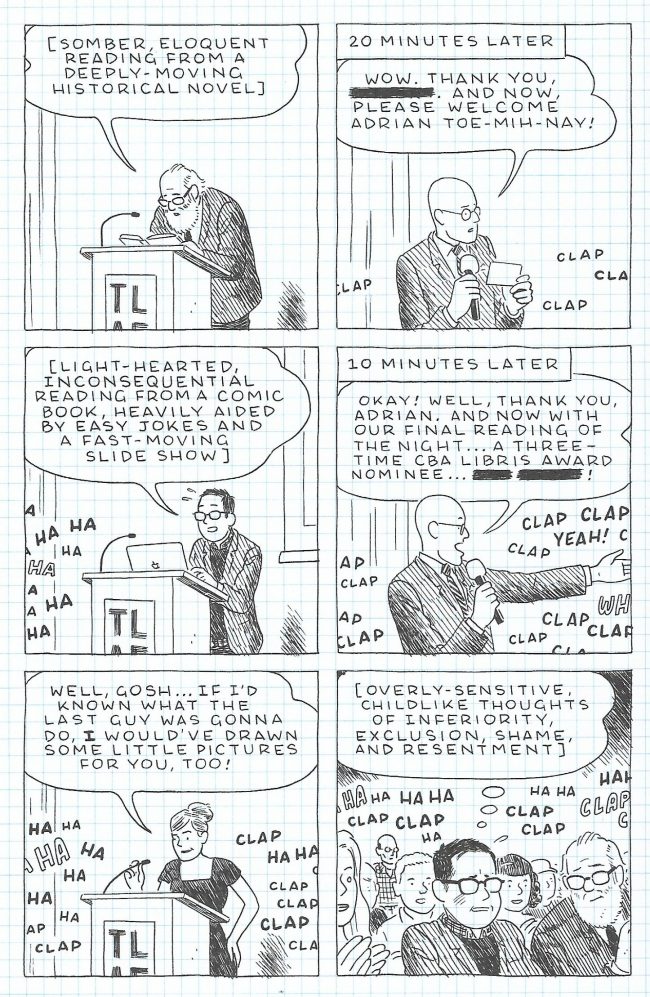

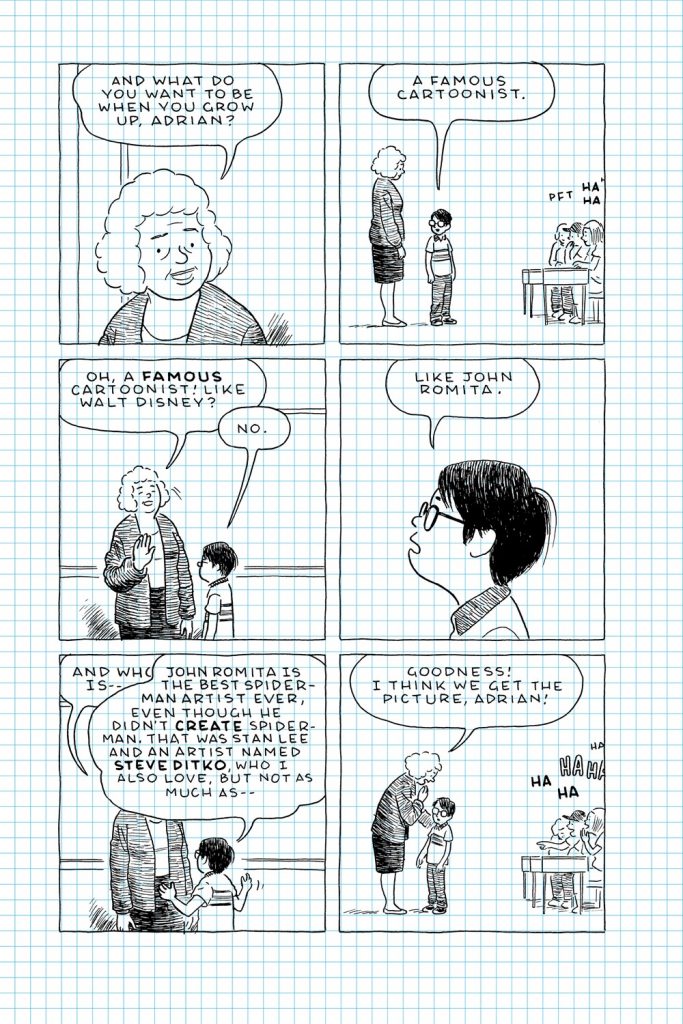

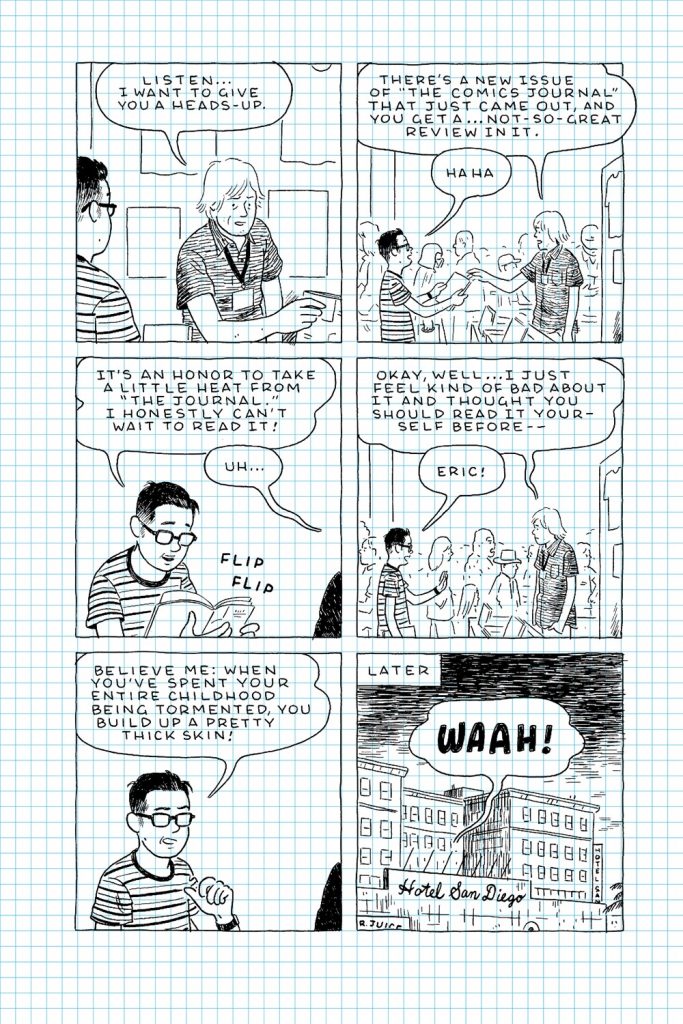

Tomine is a potent observational comedian, and most of the stories in this book are funny. Tomine is a master of cringe humor, the kind of comedy that revolves around social awkwardness and violation of polite norms. Tomine seems to be interested in examining his relationship with comics and his memory in these vignettes, and he uses his wit as a humorist and this specific self-deprecating storytelling style to generate laughs. This is the root of Tomine’s earlier success – while his work on Killing and Dying stepped away from humor and moved to storytelling that was more literary in scope, The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist is a clear return to form for the artist.

Tomine’s art style in this book, which seems less composed and, perhaps, less cinematic than previous work, serves this type of writing well. Rather than using a variety of page and panel composition, detailed shadows, shading, and the like, Tomine centers his character mid-panel, often in profile, in a 2×3 grid that is maintained throughout most of the comic. Tomine uses the grid to his advantage; it allows him to dial in his pacing perfectly so that his jokes land exactly as intended, and it works. His cartooning is also less detailed, but I think it feels more alive and more assured than earlier work. I like the hatching and stippling in the drawings of The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist, and I think it improves the way his line feels on the page. The way Tomine draws faces throughout the book is specifically quite nice, and a lot of the strength of the cringe comedy is in the little details or the reactions Tomine has to a specific situation, often only visible in the distress on his face.

When applied to his personal life, this cringe humor has a somewhat endearing effect on the reader, and I largely think that this is intentional. For fellow cartoonists and other artists working in literature, I imagine there is some empathy to be had in these depictions. Having a shitty signing at one of your favorite book stores is probably something that happens to a lot of writers. For readers without a shared background, the situations he depicts himself in engender sympathy for Tomine, and it’s clear that most of his critics in the mainstream press have had this reaction. I’ve read through much of the criticism of The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist, and a common refrain is a sympathy for Tomine’s foibles; the artist is a human, just like you, dear reader! Despite the constant parade of his embarrassments and failures, though, Tomine is the author of the book, and he makes sure to keep himself centered as a likable, if neurotic, everyman.

What I find fascinating, though, is the way that Tomine addresses the idea of memoir as an artist with The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist. Is his palpable sense of disappointment “true?” I use the emphasis on the word “true” to highlight a specific point that comes up in the criticism of memoir as a genre. When an artist, especially a cartoonist, shares their life as either a full-time or part-time memoirist, those of us in the sphere of comics criticism often fall back on the word “true” as a way to describe their work. Often, the word “true” is used in a way that indicates the reader’s connection with the material; it’s a positive descriptor, a word that generally doesn’t mean “accurate” but rather means “affecting.” I’ve made that same criticism, and it’s a weak one, a weakness that betrays a lack of observation and introspection. “Truth”, as it is experienced in memoir, is a creation of the author and an indicator of successful narrative building.

Rather than saying The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist feels “true” or “false,” it might be more accurate to describe it and other comics memoir as “open” or “closed.” How open has the artist made themselves to the reader? As my colleague Rob Clough might say, “Has the artist spilled any ink?” Openness, or at least my interpretation of it in memoir comics, can be described as a feeling of connection between the reader’s life to the author’s life; that their struggles are not merely identifiable, but feelable, that their insights are not narcissistic, but shared. Cartoonists like Kevin Budnik and Carol Tyler have a very open style of memoir writing – you can see my previous reviews for more on that subject. Lucy Knisley, a best-selling comics memoirist, has, on the other hand, a very stringently “closed” style of memoir writing. If openness is about shared connections, closedness is its antithesis. A closed memoir may be elusive in both its experiences and aims, and any connection forged between author and reader is solely forged by the reader. In the case of Knisley, everything on the page feels tightly controlled, and very often it feels like the character of Lucy in her comics and the actual artist herself are vastly different people. In truth, it feels as if Lucy the character is less an interface with the reader as she is a didactic tool. This feeling of closedness detracts from the work and makes it less accessible. On the other side of the coin, Laura Lannes is another cartoonist whose closed style of memoir makes her work all the more powerful by obscuring Lannes as a person from the reader, clouding the reader’s perception of the work.

It seems clear to me that Tomine is approaching his work in this same closed-off perspective as Lannes and Knisley. To hear tales from people who were at those same signings and events where Tomine feels mortified or embarrassed, you would think they were on a different planet. The perceptions of Tomine’s fans and audience are often vastly different – remembering full lines, insightful interviews, and intelligent conversation. While I don’t believe that there is such a thing as “verifiable honesty” in memoir comics, Tomine’s tendency to emphasize the negative shows a creator that is more interested in the punchline than the personal. Tomine is not interested in building a connection with the reader, but rather explaining a set of circumstances in a way that makes himself the butt of all the jokes. This makes his drive to garner reader sympathy through the work even more fascinating since he deliberately avoids building connections through his work.

Tomine seems to define his comics career via The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist by the things that went wrong. But take a closer look and you see something different. It’s very clear that there have been many more things that have gone right. The true joys of life – of getting married, of having children, of being a parent – are right there on the page. They’re just in the corners of stories, on the sidelines of story arcs, and in the detail that fills up individual panels. An example: at the end of a presentation at his daughter’s school, Tomine reads an email from the teacher apologizing for his offensive presentation. It’s great, one of the funniest strips in the entire book. In the last panel, as Tomine reads the distressing email, Tomine’s wife, clearly pregnant, walks by. It’s a small detail, but it’s a detail that offers an insight into the major things going on in Tomine’s life that he’s not addressing. In another instance, a dinner with his family at a restaurant is centered around a “gifted” dessert pizza that Tomine can’t eat due to food allergies. It’s easy to ignore the surroundings to see the cringe humor of the situation, but take a moment to stop and focus on the actual situation. Tomine is in good health, his wife and children are happy and healthy, and they have the financial stability to eat a meal at a restaurant. He has reached a place in his career where he can sustain a family with the work he loves. There’s a beautiful life here, hidden in plain view. While Tomine is intent on sharing his failures, his great successes are also on display.

Tomine is a successful cartoonist and illustrator, and so to see him dance around his success as an artist can be a little frustrating. So much of the economics of comics is the exact opposite of what Tomine is relaying in The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist. Ryan gets at the essential heart of these material concerns in his review, and I suspect I will see more criticism of Tomine in that same vein. But I think the center of his closed-off style of memoir is specifically the way he avoids addressing these major milestones in his life. This is most evident at the very end of the book – a major health scare preoccupies the finale of the comic, and when Tomine gets home, he addresses some of his major failings as a parent and a husband. The joke is that his wife is asleep and doesn’t hear his confession, but the mea culpa echoes backward through the rest of the comic, putting into context the things that have been left unsaid throughout. Even in this moment of cathartic realization, Tomine has to end things with a joke. There’s no resolution, no shared understanding, and therefore no connection to be had.

This isn’t to say that Tomine is ungrateful for his success, nor is it to say that Tomine has no right to be aggrieved by alternative comics. The casual racism he encounters, especially from Frank Miller at the Eisner awards, from elder artists, and even at a signing at a comic book shop, are potent observations of the whiteness of the comics arts and the way that casual racism infiltrates the artform. Tomine makes a note of how people introduce him, almost always saying his name wrong, and it’s a subtle reminder that it doesn’t take much to make someone feel excluded or othered. That said, the disappointments and embarrassments detailed in The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist tend to blend together, increasing the propensity for the reader to see all incidents presented in the book with a similar emotional tenor. Because each strip in the collection has to be a gag, the timing has to be just right, and each strip has to be constructed in a specific way. It’s an effect that pulls the reader away from Tomine, keeping him at arm’s length.

As a collection of humorous anecdotes, The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist is a winner. Tomine is an accomplished illustrator, the book is funny, and it’s a beautiful print object. I like Tomine’s writing here, and I think he manages to maintain a sense of his previous work in this memoir. But because of the closed nature of the work, I doubt that I understand Tomine any better than I did before I started reading this book. I’m left at the clifftop, not knowing if Tomine took the leap. I doubt I ever will.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply