Gabrielle Bell’s work defies categorization. If autobiographical comics can be classified as either “open” (where the artist provides a great deal of emotional context and shares these feelings with the reader) or “closed” (where a cartoonist either provides no emotional or narrative context and deliberately tries to distance themselves from the reader), Bell’s comics appear to be open at times, then often suddenly flip into magical realism or straight fiction. As a memoirist, she’s aware of the utter absurdity of the concept of “truth” in autobiography, because the artist controls every detail of the work.

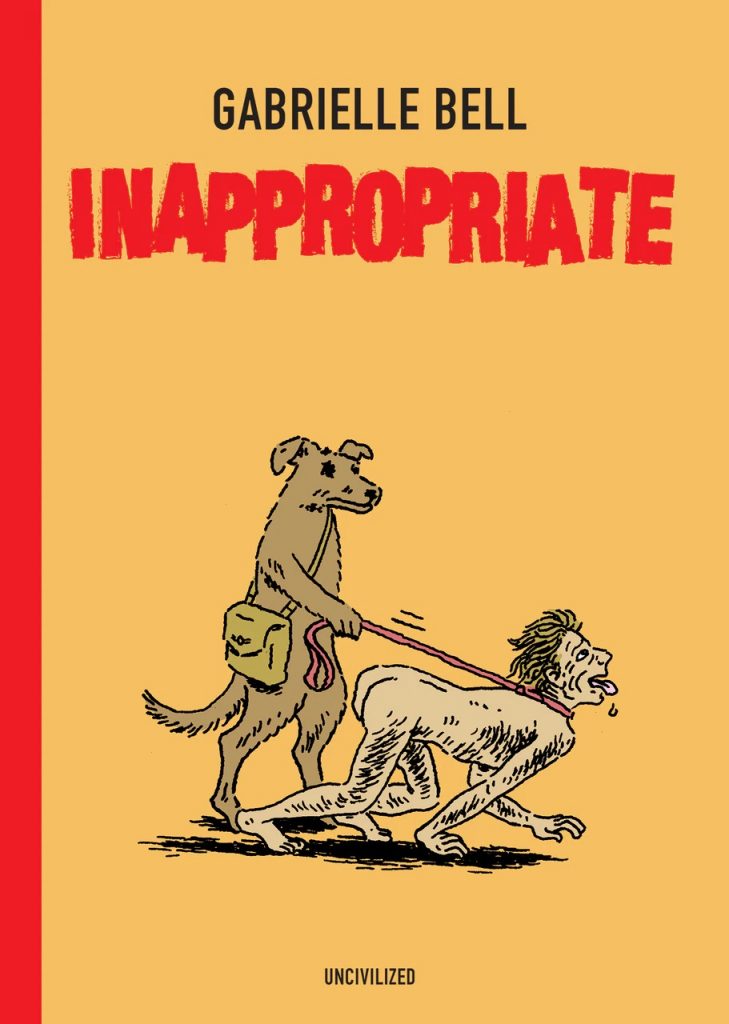

What Bell chooses to do is drop the reader straight into the middle of each of her stories with no warning or background. Sometimes it’s clear that it’s a work of fiction, like in her take on “Little Red Riding Hood,” and sometimes personal anecdotes mutate into narratives with fictive or fantastical elements, like in “Dentist,” her story about going to get her teeth fixed at a dental school. These stories appear in her new book, Inappropriate (Uncivilized Books), along with 23 other short stories. The book is a departure from Everything Is Flammable, which was mostly about a long visit trying to help her mother buy a new house after the old one burned down. That was Bell’s first attempt at something resembling a long-form narrative, and even then it often broke down into the sort of smaller anecdotes that she usually prefers.

Most memoirists, especially those who work longer-form, are trying to get across certain ideas beyond just the details of their life. Leslie Stein wanted to explore existential beauty in I Know You Rider. Carol Tyler was interested in the concept of generational trauma and mental illness in Soldier’s Heart. The way they get these ideas across is through sharing their own thoughts and experiences. This isn’t what Bell does. Bell puts a lot of distance between herself and the reader, but she shares a great deal about herself through the topics she chooses to write about, and that’s especially true in this book.

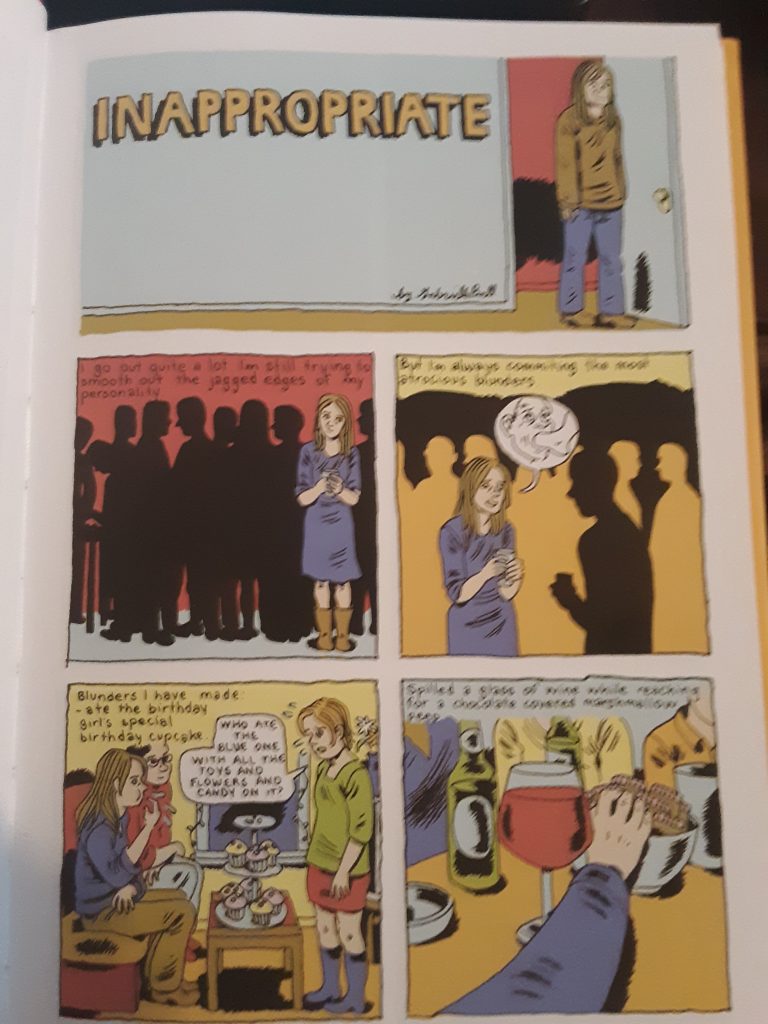

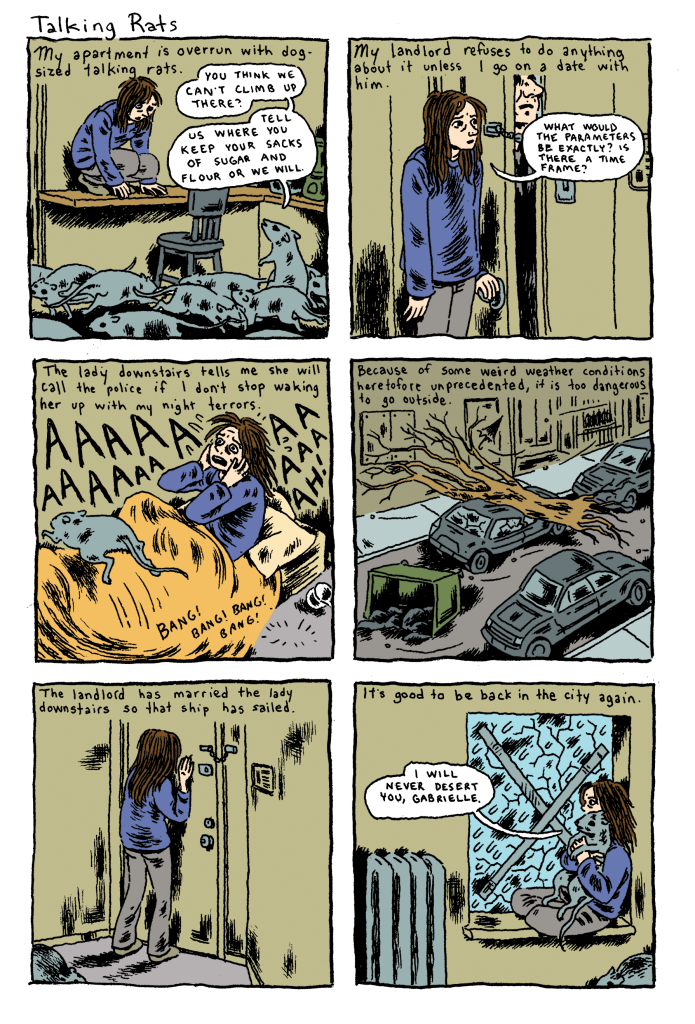

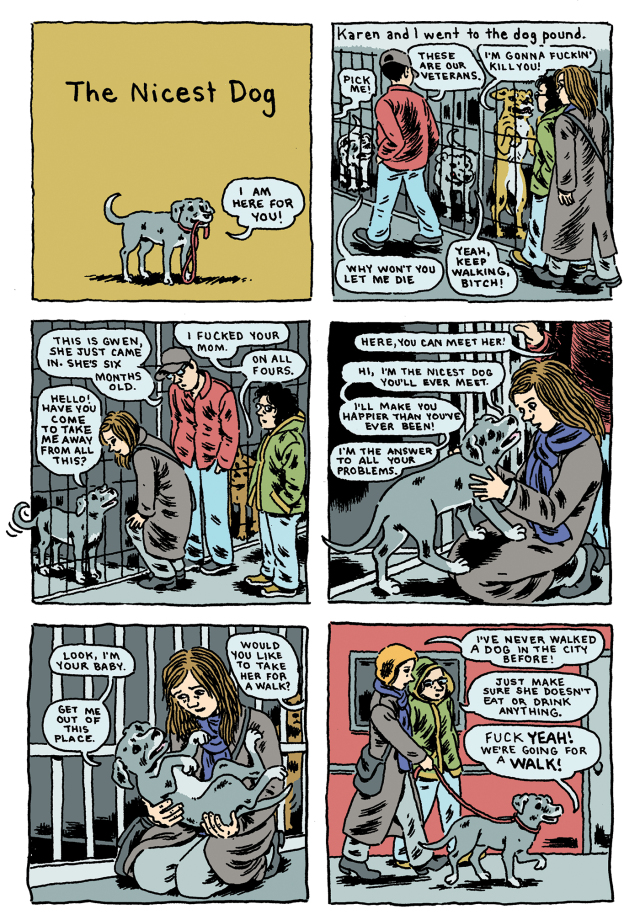

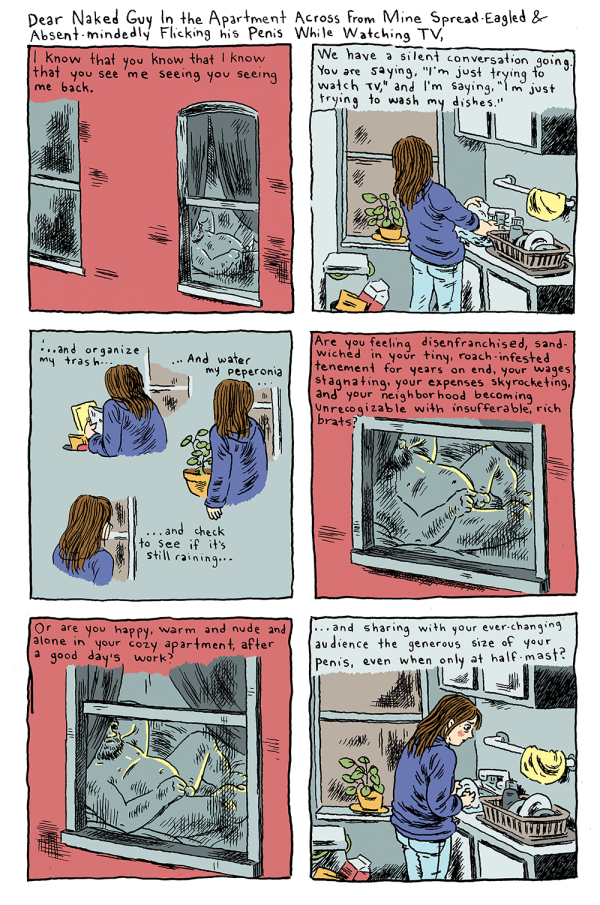

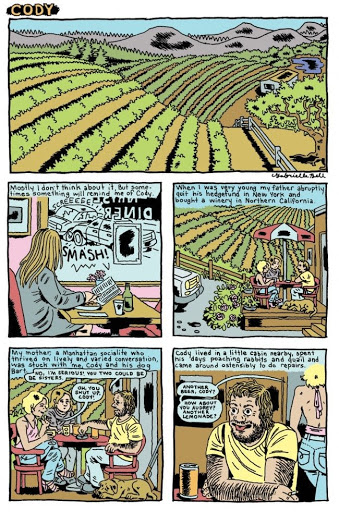

As always, Bell divides the page into six identical square panels, two by three, in an effort to create an easy rhythm for the reader and to get them to focus less on the composition of each page and more on the content. Her thin line is given definition and depth by the mostly muted use of color, and her drawings have a weight that’s also supported by her own unique style of smudgy spotting blacks. Her line has a slightly tremulous quality that even extends to her panel lines, which are clearly hand-drawn and mostly freehand, because one can see those lines wobble in places. It’s all part of Bell’s overall aesthetic, balancing a rock-solid structure against her fragile line.

There are recurring tropes in the book, and they all center around her primary contradiction as an individual. On the one hand, Bell often presents herself as a shy and anxious misanthrope who plays up her quasi-feral tendencies. On the other hand, she’s also engaged, witty, and intellectually and emotionally curious. The titular story “Inappropriate” was chosen for a reason to represent the collection, because it’s about how “[Bell goes] out quite a lot. I’m still trying to smooth out the jagged edges of my personality.” She notes that even in the isolated town where she grew up, “we were always weird.” However, despite these “rough edges,” Bell’s need to reach out to others is ever-present, even if she’s “creeping into rooms as if I might be chased out with a broom, smiling too readily, trying too hard.”

“Inappropriate” is a recapitulation of her entire career. While introducing the reader to this premise of Bell as someone constantly acting in a socially awkward manner, it segues into a sophisticated but also hilarious analysis of Carl Jung’s philosophy, a critique of Sigmund Freud, a historical digression about Marie Antoinette, and then finishes up with exquisitely painful slapstick comedy, a clever callback to an earlier premise, and a callback to one of Jung’s theories. As Bell said in Truth Is Fragmentary, “It is humiliating to expose myself like this, but it is worse to try to hide it.” Bell distances herself from the reader with her gag work and digressions while simultaneously revealing devastatingly intimate information.

She doesn’t always do this in Inappropriate. Such intimacy is doled out in dribs and drabs, as she mostly reveals herself to the reader through the aforementioned recurring tropes. One of them is her obsession with animals. This plays out as straightforward memoir, magical realism, and pure fiction. “Lipstick” imagines a sentient hipster dog walking on two legs with his naked pet human on a leash. Bell encounters them on a walk, utterly enthralled by the pet human despite him trying to hump her leg with his visible erection (charmingly infantilized by Bell saying “Look at that lipstick!”).

Bell establishes identity and agency for all of the animals she encounters in Inappropriate, even the bedbugs in “Nocturnal Guests.” As much as she hates them, she’s almost grateful for the material, getting a hug from a giant, anthropomorphized bedbug that she describes as “worthless, insidious, parasitic.” She imagines the life story of the 43-year-old trap door spider that made the news for being so long-lived as one where she constantly bemoans being left alone by her children, her mates, and even her eventual predator. Bell comes to embrace the “dog-sized talking rats” that infest her apartment in the face of apocalyptic weather. She fantasizes about polar bears in several stories, acknowledging their bloodthirsty qualities while longing to snuggle with them. “1-800-CATS” sees Bell hiring an anthropomorphic cat to exterminate the mice in her apartment, but, instead, he takes a nap, perches on her computer in order to shove his ass into her face, and makes a tuna fish sandwich. The punchline of the piece is Bell calling a dog service.

These are all gag pieces, and it’s fun to see Bell flex her precise, dry, comic sense of timing. She reveals more of herself in stories like “The Nicest Dog,” where Bell and a friend visit a dog pound as Bell ponders getting a pet. The dogs are all just dogs, but instead of barking, they speak imagined dialogue like one dog named Gwen: “I’ll make you happier than you’ve ever been. I’m the answer to all your problems. Get me out of this place.” It’s funny, but also poignant, because while Bell turns down Gwen because she wasn’t ready for a dog, she clearly had all of these thoughts in her mind. Bell later goes back to look at puppies, one of whom says “You and I are made for each other. Don’t tell me you don’t feel this,” as she imagines a dog as a surrogate for other kinds of affection and attention.

At the other end of attention and devotion are “Bucket” and “Hospice,” where Bell has to take care of their friends’ dying dog, Bucket. She also depicts him as speaking in English, but this dog is more akin to Bell’s idea of growing old and taking care of her own mother. It’s more of a grim duty that nonetheless has more meaning than an emotionally fulfilling experience, but she nonetheless tries to provide an incontinent animal with some small degree of comfort. Bell’s unique skill is to alternate quiet moments of poignancy with quiet moments of killer sight gags and to have them all fit snugly together. They are all part and parcel of the same absurdity that is her life.

The only thing that Bell seems to love as much as animals are her fellow weirdos. Her own self-image as someone who is “just barely passing” as a functioning, neurotypical person makes her a magnet for fellow oddballs. While she notes that some of them, especially homeless people, can see right through her and resent her ability to pass, this book is about her encounters with those people who are similar to her in terms of awkwardness, invisibility, and an indifference or inability to comply with certain social norms.

For example, “Inappropriate” features her friend Jami from their Jung discussion group. She’s afraid that she will blurt out that she’s forty and hasn’t had sex in a long time and then won’t be able to stop talking about it. After Bell’s own blunders at a party, the abandoned Jami, of course, starts talking about this when introduced to Bell’s friends. It’s a perfect counterbalance to Bell’s awkward antics and a funny callback. In another story, there’s the naked guy in the apartment across the way, and he and Bell have a shared understanding as secret performer and secret audience. “Doctor Emmanuel” features a bizarre, aggressive, and highly inappropriate doctor who responds to her worry about a potential breast tumor by saying “You don’t even have a handful, not even a mouthful!“

Some of the weirdos are dear companions, like “Caroline.” She’s someone who realizes that she’s socially invisible. No one ever pays any attention to her, and this realization allows her to give herself a huge retroactive raise at work and then crash a party with Bell. It goes unstated, but her energy is precisely the opposite of Bell’s, who is always noticed no matter what she tries to do. “Late March” features her frequently-appearing friend Tony, whose dry sarcasm and calm demeanor prove to be a different kind of compliment to a frazzled, cold, and anxious Bell. Of course, the ultimate beloved weirdo is the star of “John Porcellino,” in which the minicomics legend goes with Bell and a friend to see the Marcel Duchamp room at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. In particular, they go to see Etant Donnes, Duchamp’s final piece that requires going to a cave-like small room and peering through a peephole in order to see it. Porcellino passes on some wisdom about art before Bell writes him into a superb final punchline.

While there are obviously fictive elements and exaggerations in most of the stories of Inappropriate, there are only three stories where Bell makes it clear that she’s writing fiction. “My Prince” begins with Bell wondering if Kate Middleton draws comics, imagining her asking Madonna if her latest strip makes any sense. That segues into her fantasizing about being a princess, only her prince is the black sheep of the house of WIndsor, having renounced his claim to the throne to study feminist philosophy, join a cult in India, get caught up in violent protests, and wind up homeless in New York. The most hilarious part of the story is how reading Bell’s minis in a hostel brought him comfort, bringing them together as she saved him. Even in her princess fantasy, Bell still depicts herself as freaking out the royal family with her “provincial ways.” Bell is less interested in being a princess and more interested in drawing comics with Kate Middleton. Having to deal with the Royals is a heightened and exaggerated version of her awkwardness in every social situation, and it fits snugly with the rest of the stories in the book.

However, both “Cody” and “Little Red Riding Hood” are outliers. Neither story features Bell as a character, and both stories depict the kind of violence that’s rare in her work. “Cody” is given a bit of distance by being told in past tense, as a young woman named Audrey is menaced by a brutish neighbor named Cody, and his advances are ignored by her bored mother. When she tells her father about this, he comes up with a plan to ambush Cody. He kills him, and the rest of the story involves them getting rid of the body. The story is less about the trauma than it is about this unusual moment of closeness and connection Audrey felt with her father. As Bell has continued to develop as an artist, fewer of her stories are about feeling alienated and more of them are about connection, even and especially in the most extreme of situations.

If “Cody” was a serious examination of the complicated feelings on how an act of violence drew two people closer together, then Bell’s retelling of “Little Red Riding Hood” is a ridiculous send-up of this idea. Red is a drug dealer who has a romp with her boyfriend the Wolf, and she pushes him to murder her rich grandma. Bell concocts a ridiculous happy ending to this murder romp that grows increasingly bizarre with every passing page. The only things that connect this story to the rest of the book are its slapstick humor, disdain for traditional relationships, and focus on anthropomorphic animals doing strange things.

Inappropriate doesn’t blaze new territory for Bell. Instead of the sprawling travelogues and forays into rural living that marked her other books, Bell seems content to be in the city, mining its inhabitants for material. This book is a refinement of Bell’s skill as a humorist and short-story specialist that lacks none of her typically thoughtful intellectual curiosity and desire to subvert cultural mores. Bell just doesn’t fit in, but the book’s willingness to ask why winds up being more of a statement on society than a judgment on Bell herself.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply