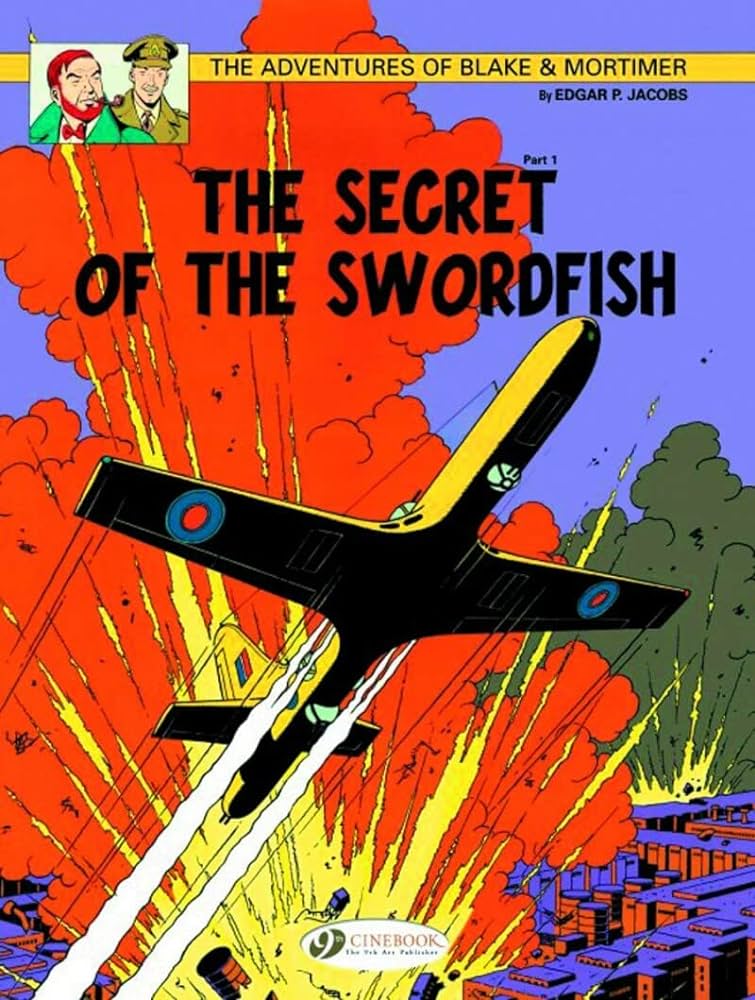

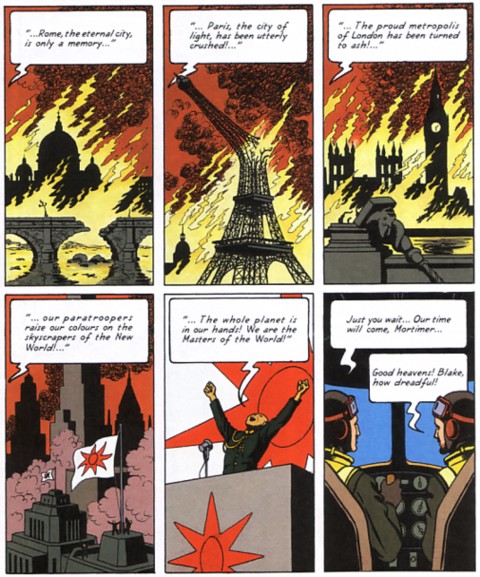

On September 26, 1946, the first issue of Tintin magazine was published. Among its contents was the first Blake and Mortimer story, created by Edgar Jacobs, collaborator, and rival to Georges Remi (Herge), the creator of Tintin. This would be the first of eight tales penned by Jacobs, and other artists and writers continue Blake and Mortimer stories to this day. The Secret of the Swordfish was the first story featuring Blake and Mortimer, set during a conflict that resembled the recently concluded Second World War. The “Yellow Empire of Tibet,” aided by the traitorous Count Olrik, launches a devastating attack that destroys the armies of the world and subjects it to the Yellow Empire’s tyranny. Thanks to the work of scientist Mortimer, a superweapon is constructed in the form of the fantastic Swordfish aircraft, which liberates the world from the Empire’s clutches.

Given that Europe had only escaped the ravages of war fourteen months earlier, it seems a strange story to tell. Of all the possible stories that would interest a younger reader, Jacobs decided to craft his own world war. You would imagine that the survivors of such a conflict would want something like Herge’s adventures: something epic and exciting set somewhere else on Earth. Jacobs drew on European speculative imaginations combined with his personal and his nation’s experience with the war to introduce his characters.

Edgar Jacobs was born in Brussels on March 30, 1904. His favorite authors were HG Wells, Jules Verne, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Maurice Leblanc. Surprising for a future cartoonist, his first creative love was opera. He became smitten with opera after attending his first performance of Faust when he was thirteen. When he was thirteen, he also made the acquaintance of Jacques Van Malkebeke, whom he could geek out with over their mutual love of British authors like Kipling and the movies of F.W. Murnau and Fritz Lang. In time, Malkebeke would become mutual friends of both Jacobs and Herge and lead both men to discover each other. Herge and Jacobs would start off friendly, though become abrasive as their respective comics competed for an audience.

From approximately 1900 to 1930, a proto-science fiction artistic movement emerged in France known as ‘Mervilleux Scientifiques.’ Inspired by developments in science such as the discovery of X-rays, radioactivity, increased understanding of the atom as well as developments in flight and public transportation (the Paris Metro opened in 1900), the genre would play a key role in the development of the bande dessine into an artistic medium of its own. Not merely limited to novels, it also spread across newspapers, advertisements, popular science writing, and children’s literature. For example, one of the genre’s key works was ‘Le siècle vingtieme’ by Albert Robida, a book that contained illustrated depictions of the Paris of the future. Jacobs read similar stories in children’s weekly comic magazines such as L’Intrepide and Le Petite Illustrate. From there he would read stories involving maniacal supervillains and superpowers realized through the science (and pseudoscience) of the age.

Belgium, especially, would witness some of the most incredible military technology of the time. On May 10, 1940, the Germans would strike decisively at Belgium, destroying their small air force, equipped with British-made Hurricane fighters, at a stroke. The Battle of Fort Eben-Emael, also on May 10th, saw German paratroopers armed with flamethrowers and explosives overwhelm the Belgian garrison at Fort Eben-Emael. With only six Germans killed, it demonstrated how swiftly modern warfare could overwhelm the unprepared. Additionally, Belgium and the Netherlands were where the V-2 rocket, one of Hitler’s ‘Wonder weapons,’ had been stationed. V-2s would bombard Belgium, particularly Antwerp from October 1944 to March 1945. Indiscriminate and undetectable, the V-2 could strike targets from hundreds of kilometers away. These developments clearly were an influence on the story, such as the climactic battle where the resistance’s hidden fortress is assaulted by flamethrower troops and poison gas (a memory of the First World War).

Since Belgium had been occupied by Germany in WW1, there was a tradition of active and passive resistance to occupation. It also had a tradition of collaboration (arguably including Herge to an extent, who continued to work with Le Soir newspaper after the Nazis had appropriated it). Flanders, particularly, was courted by the Nazis, being a Germanic language speaking region. Colonel Olrik could easily have been a member of various organizations in the real world courting Flemish sympathies. Jacobs populates his story with partisans drawn from the region (though with a myopia to be expected of the period: the partisans are heavily affiliated with the British, the major power of the region at the time, and while they fight to free themselves from the Yellow Empire, this is the service of the British Empire rather than their own independence).

Jacobs himself would be drafted into the Belgian army. The speed and completeness of the German victory was astounding, both for himself and Belgian society: “There was almost a total absence of reaction…There seemed to be no anger, no humiliation…It was like everyone had been anaesthesized.”[1] Undoubtedly, the stupor with which Belgium experienced its defeat would kindle a desire to refight the war and do it properly. With the opera no longer a viable career, Jacobs laterally moved into comics. He started at the children’s magazine Bravo, his first comic being completing a Flash Gordon comic cut short by America’s entry into the war. Blake and Mortimer emerged as prototypes in his comics series Le Rayon U in 1943. After the war, with Herge’s involvement with the compromised Le Soir affected his ability to be published in Belgian newspapers, Tintin magazine was created. Needing as much material as possible, Jacobs was offered the opportunity to publish his stories in Tintin.

The Secret of the Swordfish does show signs of being an author’s first work. Artistically, Jacobs followed the ligne claire style established by Herge, with a greater emphasis on technical detail and realistic facial expressions. Swordfish’s writing leaves a great deal to be desired, with large speech bubbles with ‘as you know, Bob’ exposition and textboxes repeating needlessly the actions that the reader can discern for themselves. It is probably the most vexing aspect of the comic. It has also been clearly extended beyond what the plot can support (there is no Captain Haddock or Professor Calculus to at least add levity to drawn out exposition). While Jacobs does an excellent job with detail and design, when it comes to composition, Herge has him beat.

Still, on the story’s merits, Jacobs succeeded: the Swordfish fighters successfully prevent the destruction of the world through nuclear war (a possibility that hadn’t emerged into mass consciousness given that the United States alone had the atomic bomb at the time). To Jacobs’ delight, his Swordfish aircraft bore a striking resemblance to the Douglas X3 Stiletto, an experimental aircraft first flown in 1952. Just as The Secret of the Swordfish hinted at the world to come, so too was it a means for ‘anesthetized’ Belgium to process the horrors of the Second World War.

Sources

Rose, Cynthia “By Jove! What did Edgar Jacobs do to comics?” The Comics Journal September 9 2019

“Edgar Pierre Jacobs” Lambiek Comic Encyclopedia https://www.lambiek.net/artists/j/jacobs.htm

“Mervilleux scientifiques” Wikipedia https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merveilleux_scientifique#D%C3%A9clin_et_disparition

[1] Rose

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply