Author’s Note: A version of this review previously appeared at Sequential State in 2019. With the birth of my second child, and a recent reread of The Man Who Came Down the Attic Stairs, I decided to revisit the review, and bring it to SOLRAD for publication. Enjoy!

There’s something bewitching about this time of year. Late October is when people go out of their way to be scared. In better times, you might go to a movie or a haunted house – this year, it’s scary enough going to the grocery store.

But more than just a time to tell scary stories, Halloween is a time of change. As a part of the cycle of growth and renewal, Halloween represents the transition from the peak of growth to the decline of life. The holiday, as secularized as it is, is a reminder of the transience of human existence. And just as Halloween is a reminder that all things are finite, no matter how much we wish they were not, the genre of horror gives us the opportunity to examine the world we live in and the assumptions we make of that world. Horror stories can allow people to wallow in hatred – xenophobia, sexism, racism – but they can also be a place to take the darkness of the world and dissect it like a frog in an 8th-grade science class.

Now, a slight confession: I’m a wimp when it comes to horror movies. An L-7 Oscar Meyer foot-long weenie. I will jump at every jump scare; I will pace around the couch as someone gets chased around a room with a knife. I’m just as likely to walk away from a movie into another room of the house as I am to actually sit through a horror movie. I admit to having turned off Texas Chainsaw Massacre (the 2003 Marcus Nispel remake) when it first came out on home video and decided to watch The Replacements instead. I’m not proud of that choice, but I am what I am.

As much as I dislike horror movies, I love horror fiction, especially horror comics. Perhaps my enjoyment of horror comics comes from my ability to control the situation – I can turn the page; I can choose the way I read the book. That means that the cheap tricks from horror movies are less effective, and therefore the decisions that cartoonists make to tell horror stories have to be smarter, more effective, and perhaps more viscerally terrifying than anything that comes out of a splatter film. To be effective, to actually scare you, horror comics need to be smart.

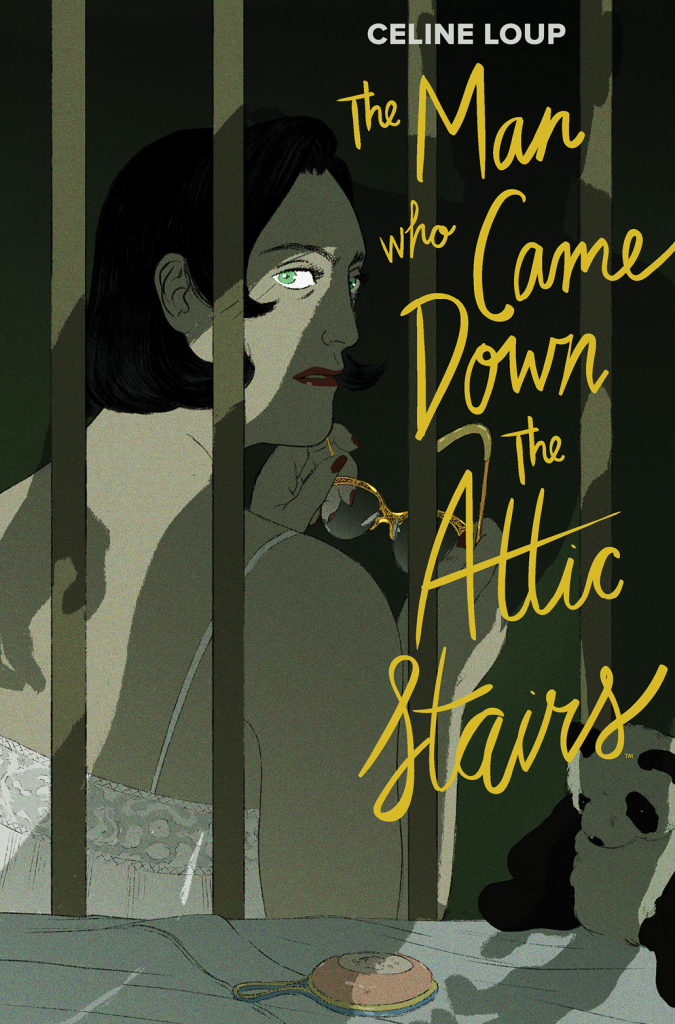

And if you’re looking for a smart comic, look no further than Celine Loup’s graphic novella The Man Who Came Down the Attic Stairs. Loup published a more explicit version of the comic as a zine, but edited and expanded it for publication with Archaia, the Boom Studios imprint. Loup’s slim European-style hardcover album features Emma, a new mother, struggling to raise her baby daughter Roslin while her husband becomes unsettlingly detached. Afraid that her husband Thomas has become possessed or replaced by some ancient horror, or perhaps that she is going mad, she starts to see a psychiatrist at her husband’s insistence.

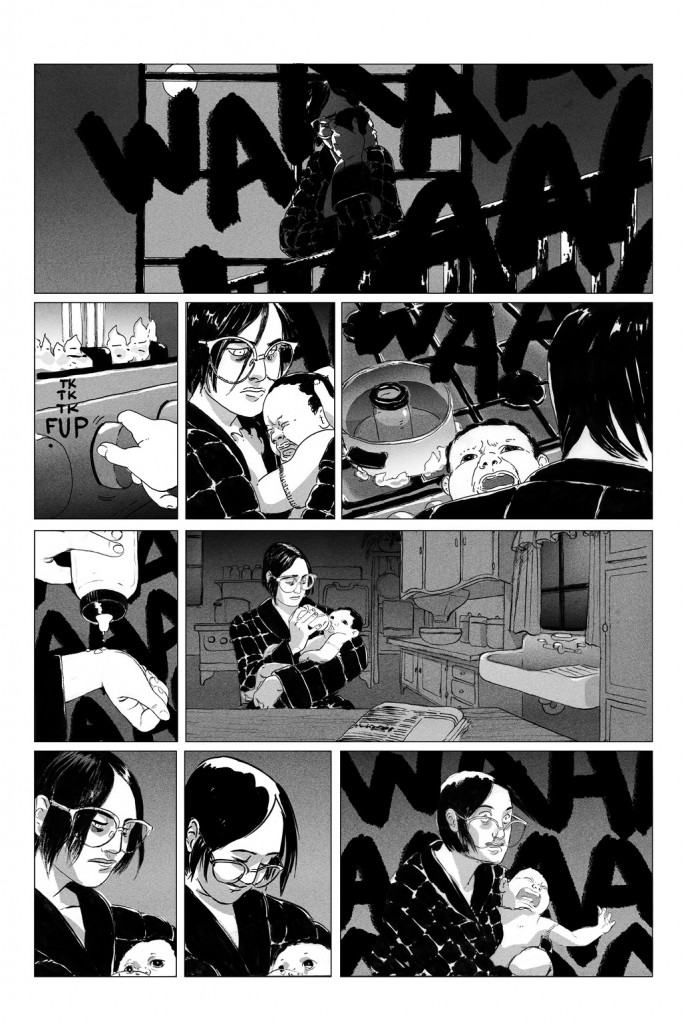

The first thing you notice about The Man Who Came Down the Attic Stairs is the beauty of Loup’s illustration and the setting for the comic. Each page is a visual delight; Loup uses a delicate line to great effect, and the ink washes throughout the book are effective at conveying its menacing tone. Loup’s images are often jaw-dropping, both for how expressive they are and for how oppressive they feel. Much of that oppression comes from Loup’s powerful lettering. Anyone with a colicky newborn knows how bad the wailing can get, but in The Man Who Came Down the Attic Stairs it’s worse – Roslin seems to be attuned to some unnatural force from the attic nursery and never seems to stop crying. Loup’s lettering of those cries is everywhere, crowding the page and making the reader claustrophobic and unsettled.

Loup also manages to capture the harrowing first months of life with a newborn in a way that feels particularly apt. As the parent to someone who is less than a month old, I can confidently say that the lack of sleep will wear even the most healthy and well-adjusted people down to a breaking point. Those first six weeks of life where the baby is awake 3-4 times a night for feedings is a millstone that, as a parent, you’ve volunteered to put your head under. Even two people sharing the duties of early morning feeding can still run you ragged. In The Man Who Came Down the Attic Stairs, Emma faces this challenge alone.

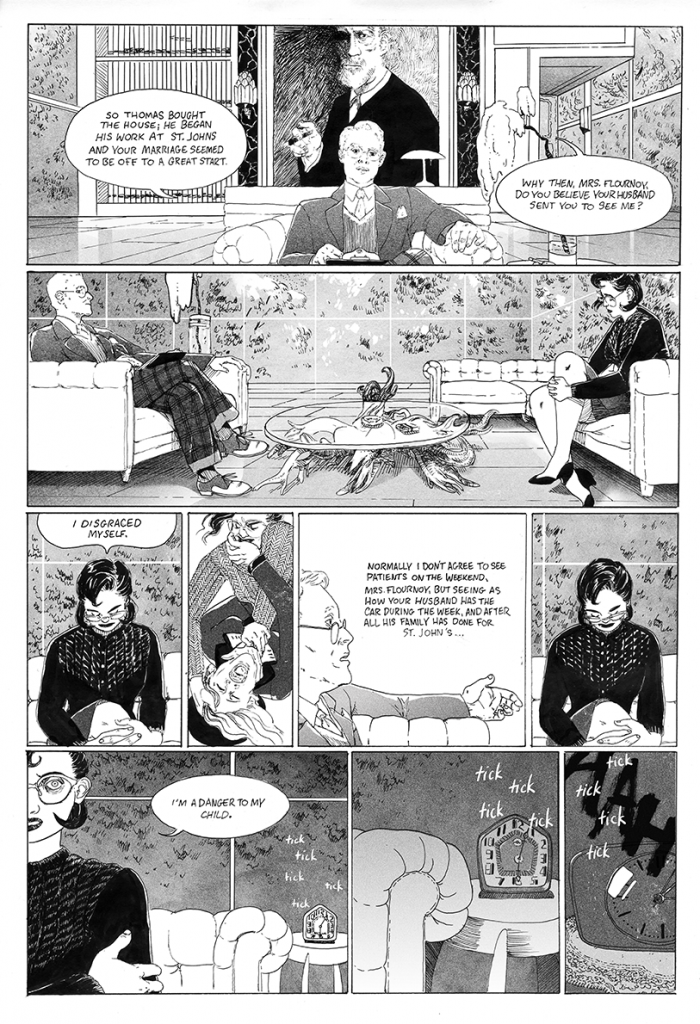

Loup manages to pack a lot into a very short comic and ramps up the tension over the course of the book until it reaches a screaming point. Thematically, The Man Who Came Down the Attic Stairs interrogates postpartum depression and the weight of raising a child alone while being expected to manage a household without help. We see Emma under enormous pressure to comply with a misogynist standard emphasized by the era in which the comic is set. Thomas wants an immaculate house, a beautiful wife, dinner on the table when he gets home from work, to have no hand in their childrearing, and to have sex whenever he wants. At the beginning of the book, Thomas is more attentive to Emma, but it’s clear that he sees her only as a means to his own ends. While the setting of The Man Who Came Down the Attic Stairs is in a past age, the corollaries in the present are evident. The demands of Thomas and Emma’s increasing fear and anxiety force readers to reflect on their own time and lived experiences.

To some extent, The Man Who Came Down the Attic Stairs is also about twilight sleep, a form of pain management used in obstetrics between the 1890s and the 1960s. During the timeframe in which The Man Who Came Down the Attic Stairs is set, childbirth was considered pathologic and unnatural, and the obstetrics and gynecology community, which was a majority male, had wide disdain for the female body. The drugs used in this procedure left women in a dissociated state and impaired the mother’s ability to bond with her child. In this state, women would often thrash on the delivery bed, injuring themselves so much that they had to be restrained and wrapped with blinders and cushions. At one point, Emma calls herself “an unnatural thing” for not feeling love for her child, but the doctors who were supposed to help her have irreparably harmed her and her relationship with her daughter. It’s also heavily implied that Thomas himself is an obstetrician and that he may have delivered Roslin, which further complicates the historical and personal truth of the story.

Another key theme of The Man Who Came Down the Attic Stairs is Emma’s forced isolation. It starts with the purchase of an ancient mansion that is set back from the rest of the town. That physical distance is crucial because it prevents Emma from seeking help from other women around town. What looks palatial in the first scenes of the book reveals itself as a gilded cage. Emma is so busy with housework and overwhelmed by Roslin’s crying that she can’t seem to have time for any other relationships. When she begs her husband for help, he sends her to a psychiatrist rather than change a dirty diaper. The psychiatrist is clearly working under Thomas’s orders because he’s not even charting her case; his writing of her mental condition is just scribbling on a blank page. Men are the only people she is sanctioned to see by her husband. This isolation is the isolation of misogynist violence, and it’s telling that the only people Emma physically attacks are female. Pitting women against each other is a classical feature of patriarchal systems, and this is a theme that appears again and again in Loup’s work.

There’s a clear thread throughout the book, a sensation of doubt that I suspect many readers grapple with. On a surface level, it seems reasonable to question whether or not Emma is a reliable narrator. There’s a reading of The Man Who Came Down the Attic Stairs that suggests that Emma is psychotic, that everything that happens in the book is all in her head. But that reading runs against the grain of all the thematic work that Loup has built on in The Man Who Came Down the Attic Stairs. The choice to read the book in that way is to fully and completely ignore the themes that Loup is carefully threading through the entire plot. In fact, Emma is the only adult character you should trust. The things that happen, however terrible they are, do happen.

The Man Who Came Down the Attic Stairs is about postpartum depression, but it’s also about misogynist violence against women. The way that patriarchal systems damage human relationships and communities is clear in Loup’s work, and her emphasis on the way that these systems ruin lives through seen and unseen violence is the foundation on which the rest of the narrative grows. In The Man Who Came Down the Attic Stairs, Loup explores the effects of the kind of violence that rarely leaves physical wounds. Thomas’ demands of Emma, and his treatment of her when he doesn’t get what he wants, is unpardonable. That violence culminates in an ending that is unforgettable. That ending is bleak, brutal, and it is heartbreaking. It tears at the fabric of you. With The Man Who Came Down the Attic Stairs, Loup delivers a fantastic, unsettling, and uncompromising vision of the horror inherent in the violence against women. If you are looking for horror this Halloween, you should find this book and read it. You won’t be disappointed.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply