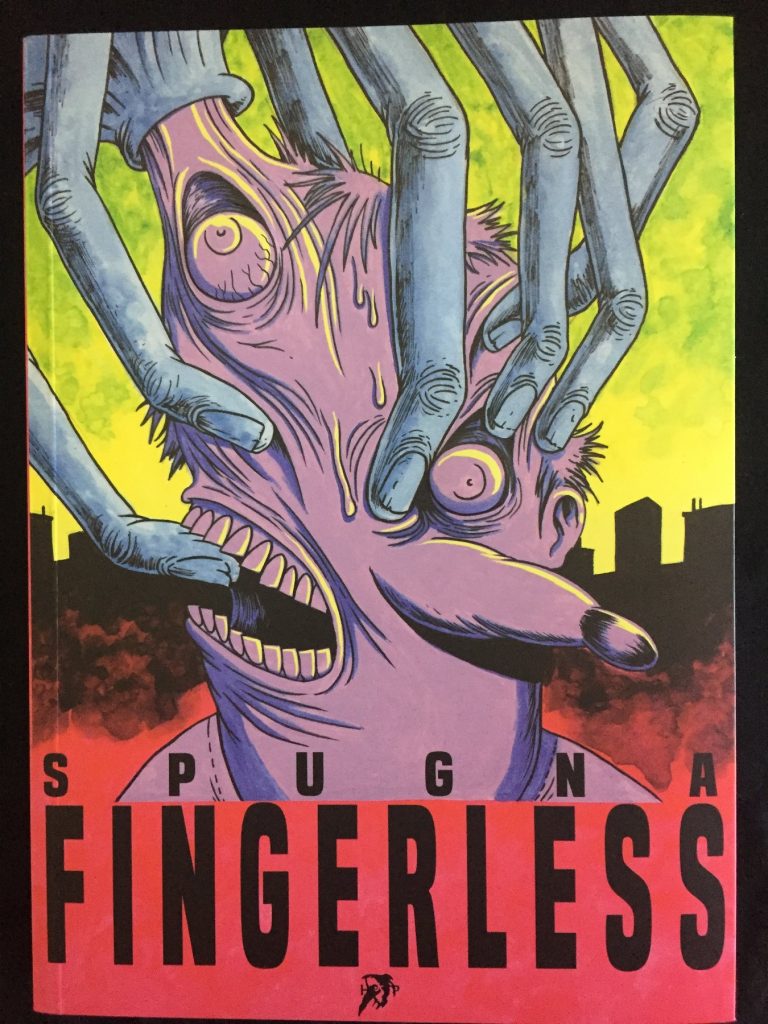

Since its founding in 2015, Michele Nitri’s Hollow Press has become well known for its high quality and sometimes oversized books, and for its love of all things strange, otherworldly, and generally challenging. Spugna’s Fingerless, one of Hollow’s recent releases, is typically engrossing and unsettling.

Fingerless is a silent comic but not an abstract one. Reading it reminded me of the sensation of reading Nicolas De Crécy’s Prosopopus, in that the action is easy to follow but you’re kept wondering who exactly these creatures are and what it all sums up to. In his previous comics published by Hollow Press, which took place in his Rust Kingdom universe, Spunga included text only sparsely and, in one instance, a language based on unrecognizable glyphs. Fingerless includes only onomatopoeia and some phrases on billboards early on. In its refusal to “say” what’s happening the book becomes something akin to a Rorschach test; the reader is left to project their own linguistic explanation onto the action.

The world of Fingerless is populated by characters nearly recognizable as human but which have a pointy, black-tipped flab of fat sticking out where a nose could be and eyes set beneath drooping skin. These character designs sent me on an acid flashback to the time I first saw the Chapman Brothers’ controversial F*ck Face sculpture. They live in a melancholically-colored world of lanky and sad-looking apartment blocks, reminiscent of the way that Gabriella Giandelli draws residential high rises.

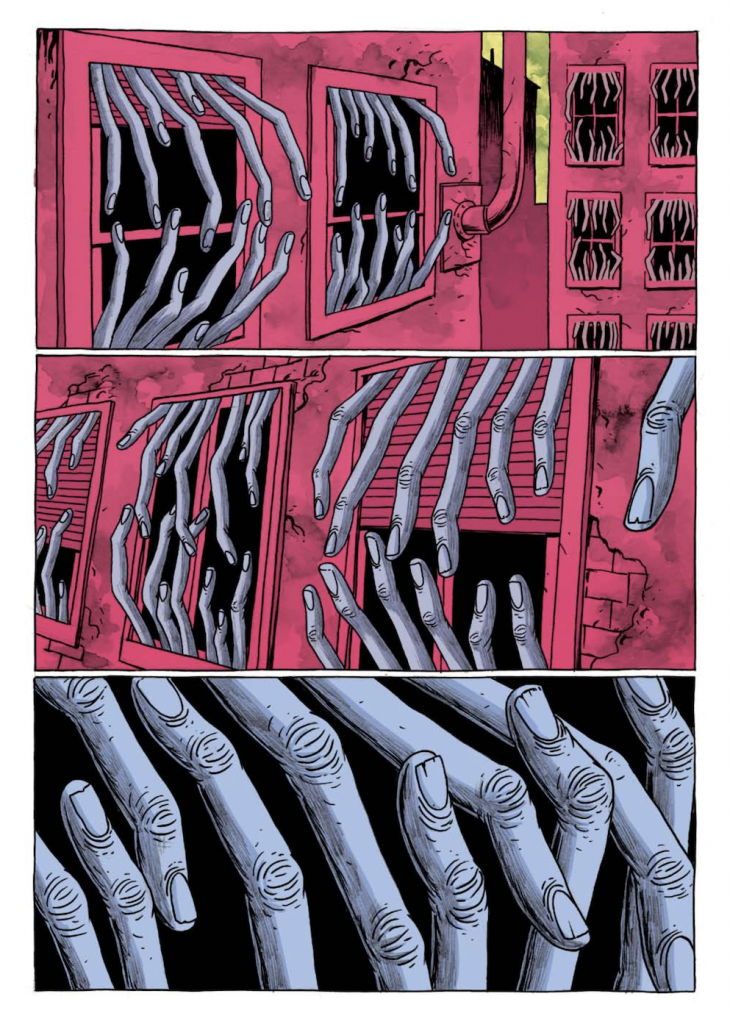

Two friends leave a bar in a drunken manner and are subsequently beaten up in an alley and sent flying into a dumpster where they’ll spend the night. This turns out to be somewhat good luck, as it’s at this moment that a plant pot-headed creature reaches down, recolors the world instantly red and yellow, and births fingers that cover windows and grasp each other, locking inhabitants in. From that moment on, Fingerless portrays a world haunted by monsters out to steal these folks’ humanity and use them as playthings, quite literally. In one sequence, the reader is treated to an increasingly gory game of tennis. The dumpster sleepers arise to find themselves the only fully formed and autonomous individuals left in this world, and proceed to attempt to avoid what everyone else has been subjected to.

I’m not afraid to say that I was quite afraid while reading Fingerless. Though it’s true that it’s clearly metaphorical, the aforementioned ambiguity leaves too much room for one’s own fears of being uncoupled from a body, or of having a personality crisis, of living in a world totally overtaken — out of nowhere, it would seem — by violent and strong forces. “It’s only a metaphor” can also be said of Pasolini’s Salò, but the viewer isn’t soothed in that case either.

Spugna’s cartooning is energetic and fleshy, interested in disturbing representations of bodies and of fears of attacks on personal liberty and agency. His digital coloring is painterly and, a little like in US Golden Age comics, he makes great use out of unrealistic contrasts so that the action on the page pops.

The ending is like some sort of cruelly ironic take on The Shawshank Redemption’s. It’s bizarrely poignant and affecting, but, like all great horror, doesn’t tie up everything in an easy resolution. The boot-headed figures that come down from the sky to steal the faces and souls and fingers of the helpless characters below may taunt my daydreams for a while yet.

Providing fear as entertainment, Spugna creates a space in which the reader can feel themselves being hoovered up, disappearing into the great mass of faceless individuals. The zombie trope plays on a similar fear. Zombies aren’t about us being scared of dying, they’re about the possibility that we’ll become undead, half-living in some permanently uncertain state. Though this may say more about me than the book, I think that Fingerless could be summarised as being about the fear of losing oneself to some other. In some ways, I thought the book may know me too well and devour me as I flicked through it. Even so, I couldn’t put it down.

Leave a Reply