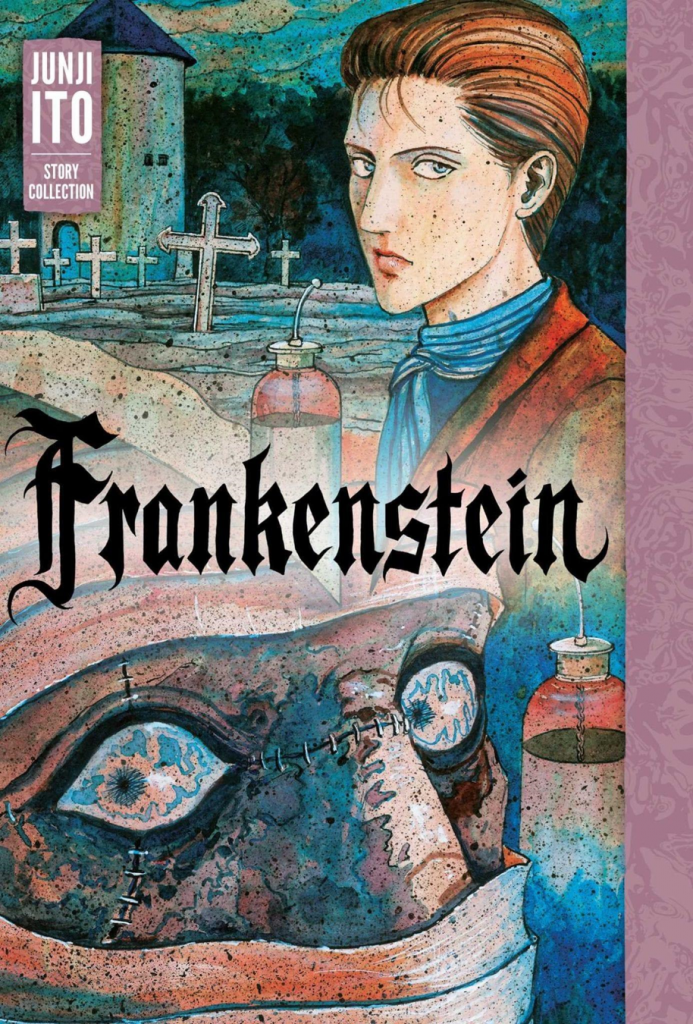

Any way you slice it, Viz Media’s 2018 hardcover English-language packaging of Junji Ito’s Frankenstein is packed to the gills — for one thing, Ito’s titular adaptation of Mary Shelley’s horror classic only takes up roughly 40-some percent of the book itself, while the bulk of the page count being taken up by a story called “Neck Specter” which features a young boy who murders his best friend and is subsequently haunted/tormented by visions of the people around him with preternaturally (hell, supernaturally is probably more accurate) long necks, and a series of early-days strips revolving around a recurring protagonist named Oshikiri who falls victim to a subtle “invasion” of dark, parallel-reality versions of people he knows, himself included — but while this “bumper volume” presentation can probably be explained away by the publisher’s need and/or desire to get as much of the Ito content they hold the rights to out into the hands of an eager fan base, it’s nothing compared to the sheer bulk of visual information (barely) contained by the main feature itself. In a funny way, then, Viz editorial’s business-driven choices reflect Ito’s artistic ones, but fair warning: it takes a little while to suss this out, and the early going is, harsh as it may sound, at least a little bit of a slog.

It’s a breezy enough slog, though, paradoxical as that no doubt seems, but given that most readers are likely coming to this work already well-familiar with the unofficial master of horror manga’s track record for the grotesque and the obsessively-detailed, the dry and surprisingly faithful re-telling of Shelley’s story initially offers little for the artist to sink his teeth into — or for audiences to get particularly excited about. Patience is a virtue, though, of course, and while Ito’s sunlit Victorian rooms, fancy dress, and wedding planning — beautifully and delicately rendered as it all is — curiously and conservatively offers no visual translations of the confining and restrictive social norms and customs of the time, it mercifully gives way to what we’re all here for, that being sheer, unrelenting terror. And that, as you’d expect, is when things get well and truly interesting —

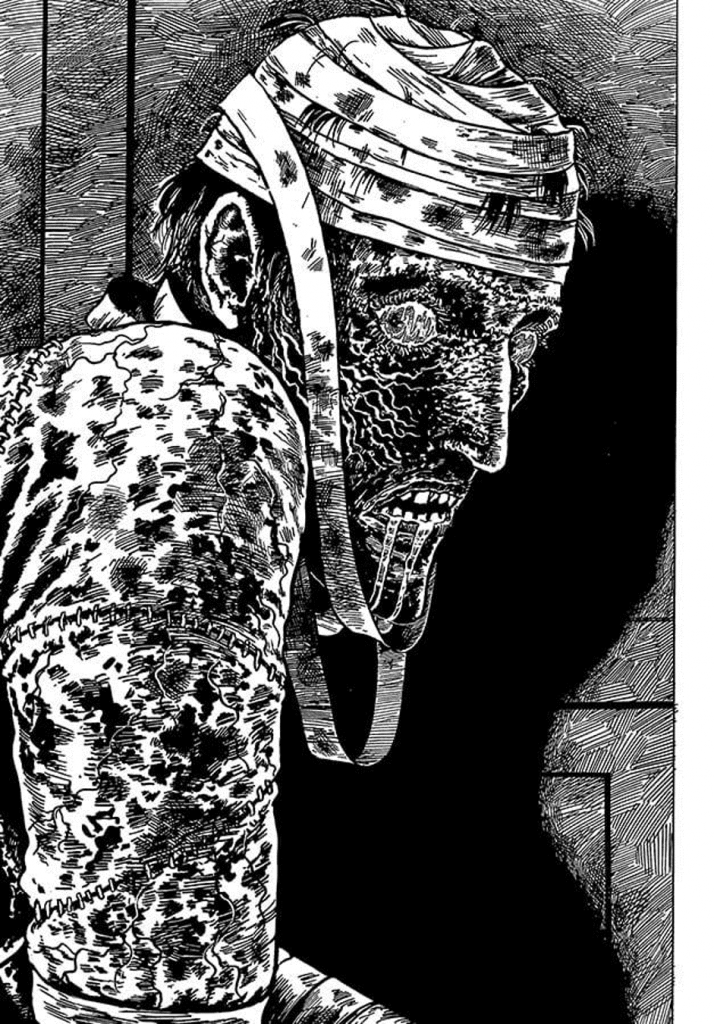

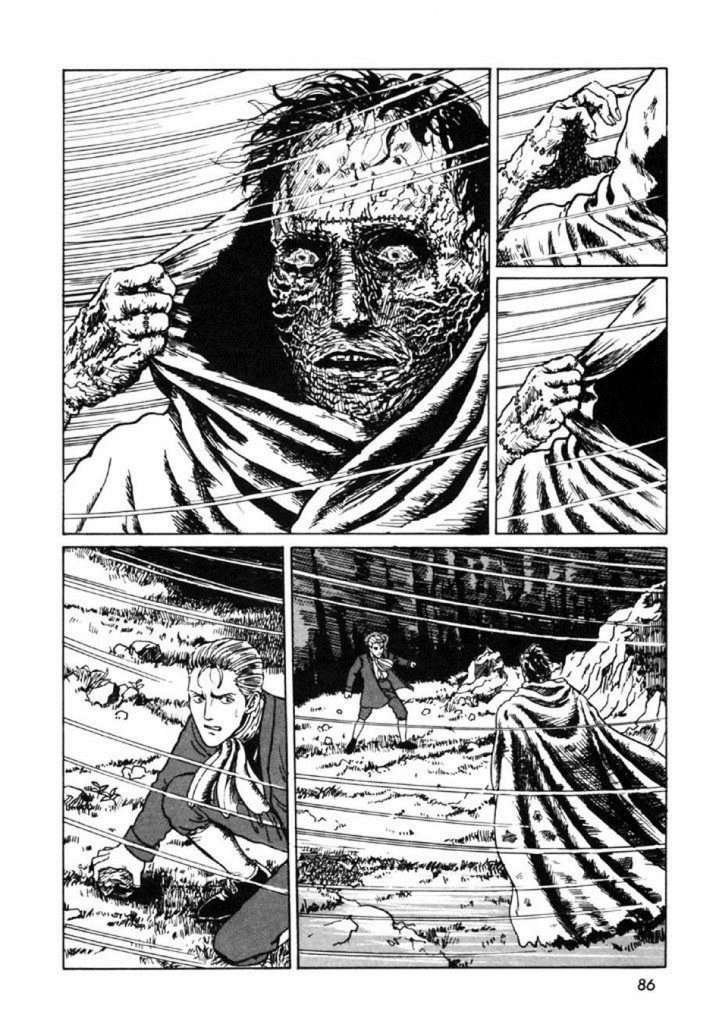

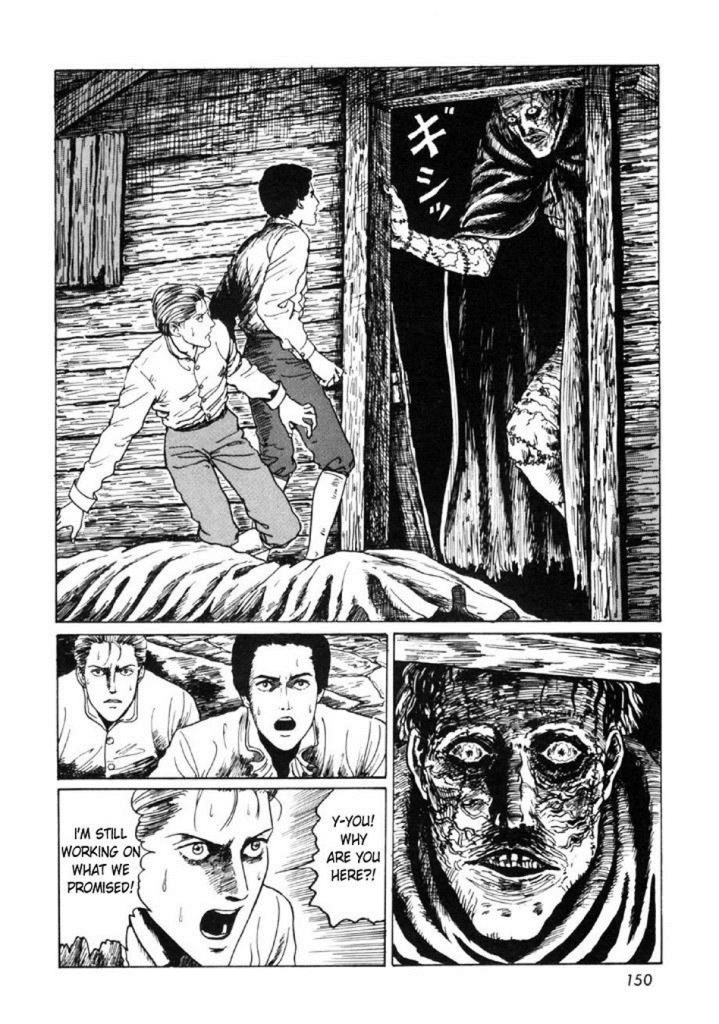

Ito’s interpretation of Dr. Frankenstein’s monster is a revelation, an admittedly literal realization culled straight from Shelley’s text, but one that has arguably never been presented in a manner so altogether effective by anyone this side of Bernie Wrightson. Ito’s monster is a hulking, space-devouring monstrosity of epic proportions and intricately-rendered details. The idea of a shambling brute comprised of stitched-together corpses that has been brought to life in every form of media from literature to cinema to comics is brought to unlife here, and that’s the crucial difference. Ito’s monster can barely be contained within his panels and pages, constantly pushing against the physical boundaries of the flat, two-dimensional image in a manner that borders on the metafictional, the artist utilizing the strictures of the format itself to emphasize the outsized nature of the unnatural horror he’s depicting. It’s all too much by design and in the best possible way. Or worst, I suppose, being this is a horror narrative — arguably even the prototypical horror narrative.

This shift is more than just visual, though. While Ito’s script in Frankenstein doesn’t take any serious liberties with its so-called “source material,” it does become more appropriately economic at key junctures. He intuitively (and accurately) knows when his duties as a writer are best served by taking a back seat to his duties as an artist. This may seem like a “no-brainer” to modern readers, but considering both the “purple” nature of Shelley’s prose and the downright over-wrought scripting of many earlier comics adaptations of it, clearly the idea of telling this particular tale through mainly visual means is far easier said than done. It’s this critic’s contention that Ito manages this feat by concentrating his considerable creative prowess on one crucial aspect and riding it for all it’s worth and then some.

Unsustainability is the key idea and emotion that Ito meticulously, even mercilessly, drives home from the time Frankenstein’s monster first stands to the story’s end. His shambling, cruel mockery of existence can’t possibly move; can’t possibly think; can’t possibly develop agency for itself; can’t possibly even be. And even if it defies all this and can, well — it shouldn’t. From its oozing, festering sores to its bursting stitches to its bloodshot eyes to its salivating mouth, this is a being that looks, feels, and is intrinsically wrong; it’s an abomination worthy of pity, certainly, as events play out, but no less spine-chillingly hideous for that fact. Destruction of life, we’re told, is the single most evil act one can conceive of or commit — every legal system in the world is predicated upon such a belief — but in Ito’s hands, it is its attempted creation that is the true evil, the true abomination.

None of which precludes this new interpretation of perhaps the most famous horror story ever told from being the tragedy — hell, the double tragedy — it’s always been, though. Both Victor Frankenstein and his creation are inextricably entwined with each other on a divergent-but-mutual road to damnation, and that die is cast from the moment the creature awakens in the lab. The sheer mass of the creature’s being, in fact, is nothing compared to the mass, the scale, the weight of its fate — so painfully-well-crafted is Ito’s rendering throughout that the very idea that things could ever be any other way for either principal protagonist is a non-starter, a folly, a pipe dream. Crushing finality encroaches early and only tightens its iron grip as the book continues — or, if you prefer, spirals downward. And therein lies the true horror: creating life when one shouldn’t is only a gateway here, the key incident that, if you will, gets the ball rolling. It is inevitability, immutability, even pre-destination that is the true existential evil in Ito’s take on Frankenstein — and there’s nothing that any being (living or unliving, a product of nature or a product of mad science) can possibly do to escape their fate.

Ryan Carey is a lead writer for SOLRAD and a prolific comics critic. You can find more of his writing here.

If you like the work we’re doing here at SOLRAD, please consider making a tax-deductible donation to our parent company, Fieldmouse Press, to help keep the lights on. Thanks!

Leave a Reply