Hazel Newlevant has done a lot of autobiographical comics, but most of them are roughly contemporaneous with their life at that moment. No Ivy League is their first full-length graphic memoir, and its focus is on an experience from a decade ago. The difference between being 17 and 27 is a wide gulf, especially for Newlevant, who has been quite open about their transmasculine transition. No Ivy League, though, is about transitions and awakenings of a different kind, as Newlevant’s “Hazel” character slips out of their home-schooled, bourgeois safety net to find the harsh realities of kids with very different experiences from them. No Ivy League is a bildungsroman where the knowledge Hazel gains over the course of the book is transformative, but the real lesson they learn is just how much they didn’t know about the world.

There’s another way that No Ivy League is different from Newlevant’s earlier comics. There are a number of different ways to do comics memoir. There’s a first-person narrative style, where the observations of the protagonist generally tend to supersede all other points of view. There’s vignette style, which often shifts point-of-view in favor of short episodes that tend to have a tenuous narrative connection but which often have a strong emotional connection. Indeed, for most memoirs, that emotional narrative is usually more important than a conventional plot. That is true in Newlevant’s earlier book Sugar Town, which is more about a particular kind of romantic feeling and experience than it is a real story. No Ivy League is the rare example of a story told from the point of view of the protagonist but without first-person narration. This is a deliberate decision on the part of Newlevant’s, because they want to carefully establish who Hazel is and what their life is like before they experience events that shake those foundations. The various visual and textual cues that make up the backbone of the plot itself are crucial in understanding the book’s themes.

Newlevant’s use of tone is masterful throughout the book. They make Hazel a likable enough protagonist in the opening scenes, as the pointy-nosed protagonist hangs out with their homeschooled friends, makes out with their boyfriend, eats vegan food, and plans a cross-country trip to see a concert. They seek out a summer job not out of necessity, but to help fund their trip with their friends. Hazel and their friends work on promotional videos for homeschooling, hoping to win a contest for a cash prize. During these scenes, Newlevant plants little clues as to just how insular and privileged their life is: making enough money for her to be homeschooled, fancy equipment for their computer, and other trappings of comfort. It’s subtle and doesn’t seem remarkable until later in the book, when Hazel makes some hard realizations about their life.

The bulk of the memoir focuses on Hazel’s summer job working with the “No Ivy League,” a park department job that hired teens in order to clear out invasive English Ivy from Portland’s forests. Coincidentally, it seems, most of the kids Hazel works with are African-American, Latinx, or Russian natives. In other words, either immigrants or people of color. Early on in their interactions, it is clear that Hazel wants to portray themselves as “down,” asking one of the African-America kids who their favorite rapper is. His response is a sneering dismissal, and it isn’t the last time they get that kind of reaction. For example, when they make a point of (politely) refusing some chips after checking the ingredients and seeing they aren’t vegan, the reception they get is icy–like Hazel thought they are better than the others. In another scene, Hazel feels humiliated when someone says, “No white girl has rhythm like that” when they are shimmying a bit.

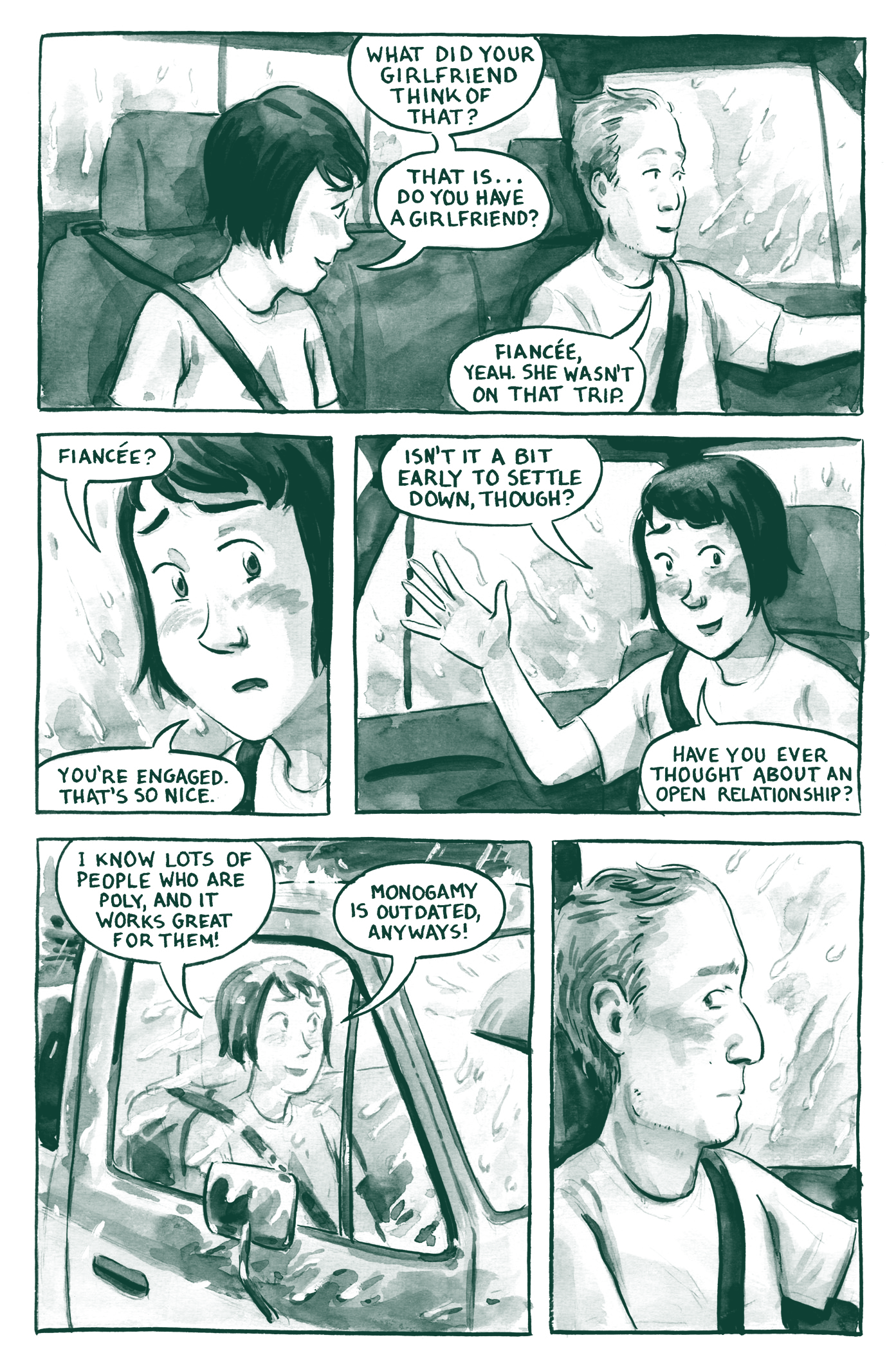

Newlevant intimates that Hazel’s inability to make friends and be seen as cool is perhaps the first time this has ever happened to them. All of this is accomplished through Newlevant’s sensitive brushwork and attention to body language. One thing that Newlevant gets across is that privilege begets entitlement. Hazel thinks they are cool and clearly feels that they should be treated that way. They brazenly hit on their 32-year-old boss, playing the Rick James song “Seventeen” in the car with him. That song includes the less-than-subtle lyrics, “She was just seventeen, but she was sexy”. The look of sheer terror on his face as they are giving him their best seductive look in that panel is hilarious. Later, Hazel suggests a poly lifestyle for their boss when he mentions that he is engaged, and he politely but immediately shuts that suggestion down. Though Hazel cries afterward, Newlevant depicts that scene more like a spoiled kid who doesn’t get a pony rather than being genuinely emotionally crushed.

As the story proceeds, Hazel slowly gets to know their co-workers and starts to feel more accepted. Newlevant seems to be telling a story about how Hazel finds ways to fit in. Then there are two incidents that point out certain double-standards. The first is when one of the boys steals one of the girls’ erotica novel and starts reading it out loud as a way to humiliate her. The second is when one of the boys loudly asks Hazel if they want to suck his dick. The difference is that the girl in the first incident doesn’t report it, but Hazel did. The result is that the boy is fired for sexual harassment. Newlevant depicts a lot of interesting ambiguity here. The misogyny and harassment present amongst the boys are real and palpable and shouldn’t be minimized. On the other hand, the other kids noted that when a white girl speaks up about it, a black kid gets fired. This isn’t Hazel’s intent, but they are naive as to the ramifications of their actions. Hazel realized that the intersection of various kinds of oppression makes day-to-day interactions complicated.

That incident unravels a lot of threads in Hazel’s understanding of the world. They feel enormously guilty when the boy who harassed her is fired, especially when they learn that he really needs the money. When Hazel brings this up to their boss, he reveals that this program is actually designed for “at-risk youth,” and the main reason they were hired is that the bosses had hoped Hazel would be a good influence. Again, subtle, institutional racism rears its head. When Hazel brings all of this up with their mom, their mom notes that this kind of interaction is why they had decided to homeschool Hazel in the first place. Their mom then reveals they had been badly harassed as a result of being part of a school integration program.

Learning that they are being homeschooled as a reaction to integration leaves Hazel crestfallen, as this is a perfect example of how even the most progressive white people can engage in racist behavior. There’s a pointed scene where Hazel tries to discuss this with one of their co-workers who isn’t black, but he isn’t having it. He rightly says that if Hazel wants to talk about it, they should do so with their African-American co-workers. Chastened, Hazel starts to ask questions. Why weren’t there any black or brown people in their homeschooling group? Instead of demanding that others give them information, Hazel educates themselves, looking up Portland’s shameful history with regard to race. Founded as a whites-only community, its race-related problems continue to be a huge issue in spite of its liberal reputation.

The denouement of No Ivy League emphasizes that the essence of the story is not that Hazel learns a lot of answers, but rather that they finally start to ask the right questions. An argument with an African-American girl about privilege when Hazel declines to take a frisbee as a prize later leads to a discussion and even a little understanding. When Hazel wins the contest for the homeschooling promotion, they are now embarrassed at how naive and insular their video was. They finally understand that homeschooling is a privilege that many people simply can’t afford. Newlevant is careful not to portray Hazel at this point as someone who has suddenly achieved enlightenment, but rather as someone who starts to think about other people’s feelings and perspectives instead of perseverating on their own. True self-awareness of one’s own biases and assumptions is the first step in developing empathy, Newlevant argues, and the end of the book is best seen as Hazel’s fumbling, fledgling first steps at trying to understand others. More to the point, Newlevant argues that this is a journey that never ends.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply