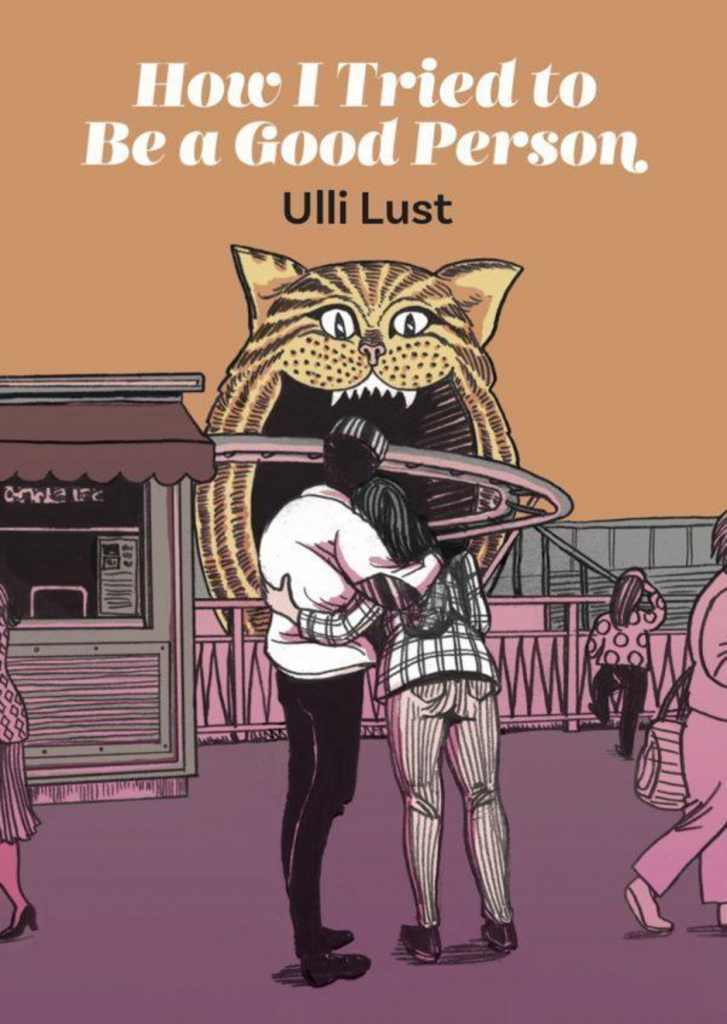

Following directly on from her Ignatz-winning 2013 memoir Today Is The Last Day Of The Rest Of Your Life, Austrian cartoonist Ulli Lust’s latest, How I Tried To Be A Good Person (Fantagraphics, 2019), is equally as formidable a work, clocking in at a whopping 368 pages, and equally as frank and confessional in its tone and temperament, but rest assured: it stands on its own as a self-contained work of self-examination, as well as a painfully accurate and hyper-detailed reminiscence on a momentous period of time in the author’s life and the people who made it that way.

Crucially, the title itself gives away both the point of view and the narrative strategy of Ulli Lust: it admits to shortcomings, if not outright failures, but also couches them in an entirely human bit of self-justification: she did, after all, at least try.

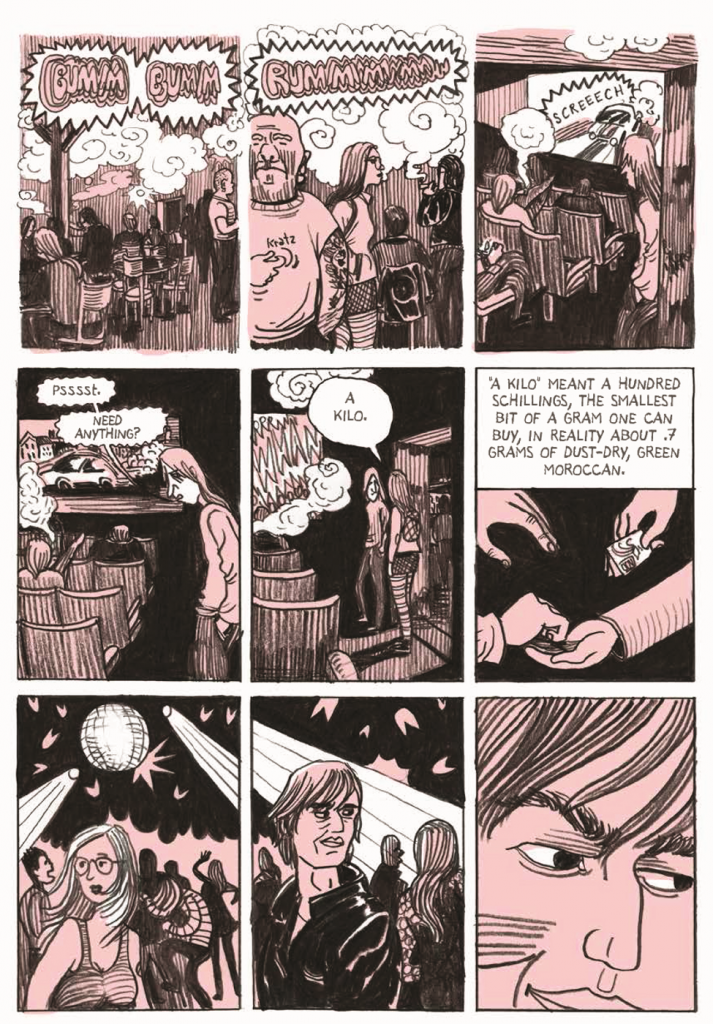

And it’s probably fair to say that, as a young artist in 1990s Vienna struggling to balance her urge to create with her need to take dead-end jobs to survive, as an anarchist activist looking to balance her idealism with her need to remain grounded in social and political reality, and as a single parent required to balance the needs of her child with her own need for love and intimacy, trying is probably the most — and the best — Ulli Lust could reasonably be expected to manage. The conflicting stresses exerted by all these diametrically-opposed forces goes some way toward explaining why she both missed and deliberately chose to ignore the various alarm bells that were going off in all directions as she pursued romantic relationships with two men concurrently.

“Bachelor number one” is Georg, a warm, affectionate, and caring actor 20 years Ulli Lust’s senior who provides almost-fatherly guidance and stability but can’t keep up with her physically or sexually — and that’s where “Bachelor number two” comes in, a Nigerian immigrant Lust’s own age named Kimata, who brings to the metaphorical table the across-the-board excitement Georg is incapable of but comes with plenty of baggage of his own in that he’s emotionally volatile at the best of times, downright dangerous at the worst — and as events progress (and as you’d no doubt expect), “the worst” becomes a more and more frequent occurrence. Lust ends up becoming downright fearful for her life, in fact, and not without justification.

Interestingly — and bravely — Lust’s narrative views both Gerog and Kimata as full people, with unique backgrounds and life experiences unto themselves entirely apart from their relationships and interactions with her. In Kimata’s case, especially, she gives due consideration to his difficult relationship with his family and his increasingly estranged relationship with his own son — something she fears is happening with her and her kid, Phillip, who is often more notable for his absence than anything else, and with whom she shares reasonably warm and cordial relations, sure, but always with an undercurrent of emotional distance that is pretty well out of step with how most parents and children act toward each other. Hell, if I had to put it bluntly, I’d say Lust seems a lot more like Phillip’s aunt or big sister than she does his mother, showing him affection with more than a bit of remove, and not playing a tremendously active role in either his educational or social development. One gets the distinct impression that having a child doesn’t trouble her overly much, but raising a child is something well beyond her emotional abilities.

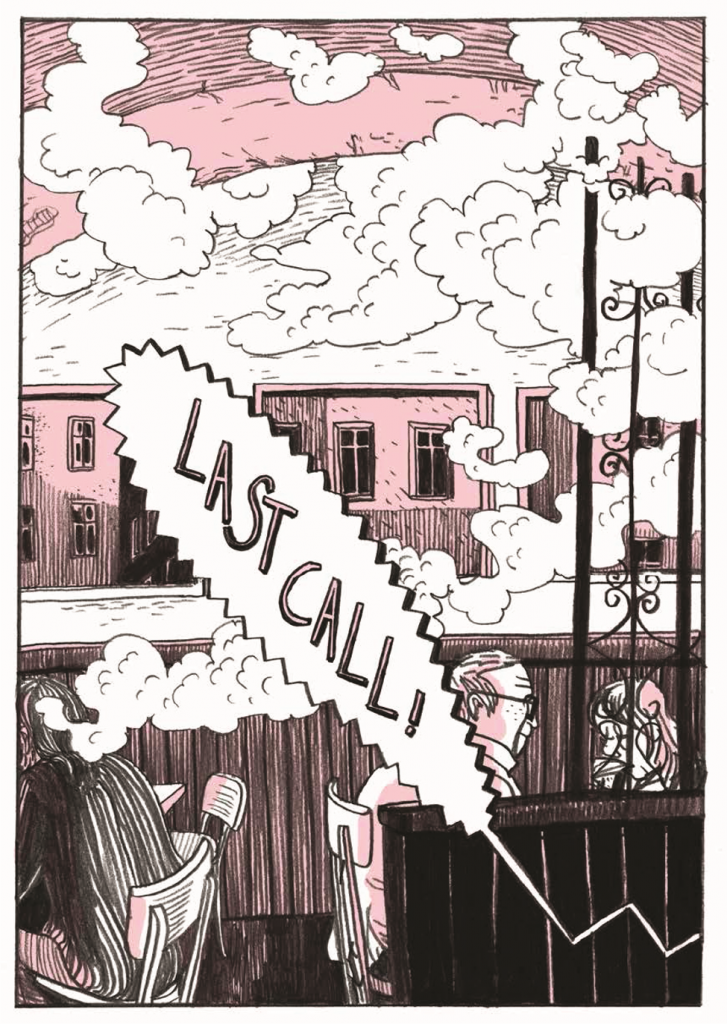

One of the most interesting choices Ulli Lust makes is in her depictions of her interior and exterior lives. Her illustration is uniformly expressive and emotionally literate, teasing out the details in people’s reactions and their body language, but while she keeps matters admirably “workaday” when drawing consensus reality, all bets are off when she’s showing her interior mental landscape. She’s not afraid to show things as being as surreal and “trippy” as she views or, more importantly, feels them to be. These two realities combine, conflate, even conflict during the book’s many — and intensely revelatory — erotic scenes. It’s the overall character and tone of Lust’s phantasmagoric illustrations of these moments that communicate her dangerous attraction to Kimata, and her outright need for the kind of emotional and physical intensity that his love offers, far more than mere words ever could.

In point of fact, Kimata becomes an addiction at best, obsession at worst, for her — even (arguably especially) as the relationship becomes more combustible. While Ulli Lust is more than blunt about intimacy being her drug of choice (a paradigm that she traces back to her own childhood, which comes in for a fair bit of examination itself), she nevertheless is telling this story from the vantage point of the present day, and, as such, she in no way shies away from intimating that she should have known better. Hell, maybe she even did know better at the time.

Even with all these various and sundry ups and downs in mind, though, this is in no way anything so unambitious as a mere “cautionary tale” or litany of regrets. Clearly Ulli Lust is still coming to terms with the lessons learned from this period, but while her holistic point of view that sees the good and bad in everyone, herself included, can at times be devastating (there are numerous instances that feel very much like she’s making justifications for her abuser), it nevertheless hews far more closely to emotional and strictly situational accuracy than perhaps any other work of comics memoir in recent memory. No one is entirely innocent in this story, no one is entirely guilty, and none of the principals involved may even be entirely in control of their actions or reactions.

Life’s a messy thing, love doubly so, and while Lust’s philosophical commitment to her own personal autonomy ends up being the closest thing to a “saving grace” this narrative offers, it also ensures that she can’t simply let go of these tumultuous memories and must examine both what led to them, and what she can take from them going forward — a process that is still ongoing, and that will no doubt continue even now that this work has been completed.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Check out more of our Memoir week coverage here.

Leave a Reply