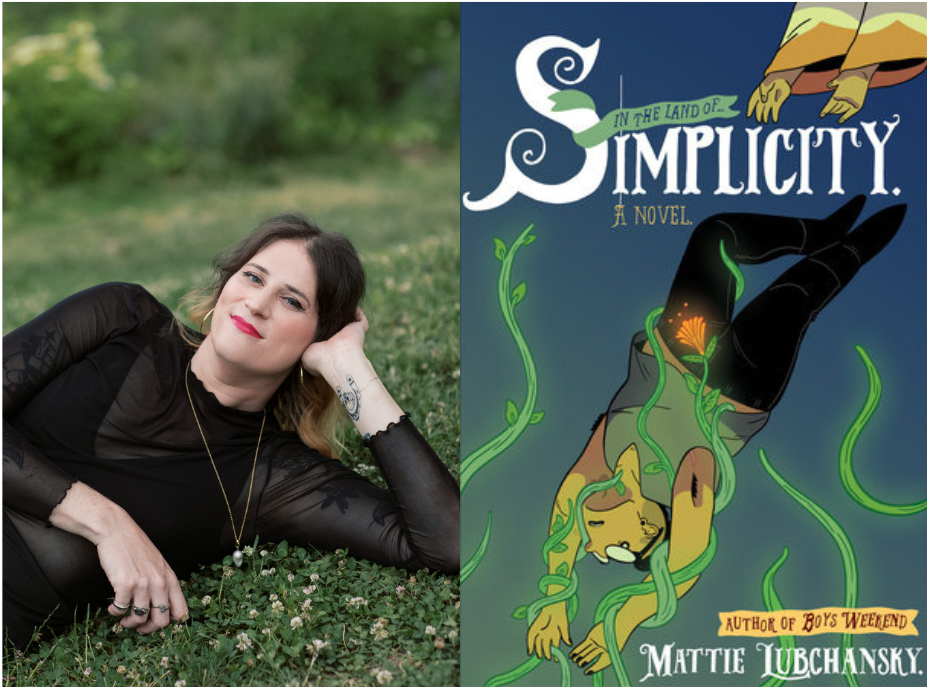

The Catskills have long provided an escape from society. But in Mattie Lubchansky’s Simplicity, gone are the bungalows and resorts and summer camps of America’s past. In their place is a new order, a perfect society created by The Spiritual Association of Peers in 1977. The book opens in 2081, on a tour for the museum where Lucius works, and follows his descent into the community as he immerses himself into the unknown to complete his next project. Along the way, he tries to answer questions about their unique way of being, but his earnest efforts are met with distrust. Who are the people of Simplicity? Where would they fit into the greater story being told by The Museum of the Former State of New York through their exhibits? As the already shaky lines between investigation and immersion begin to blur, so too do the boundaries between Lucius’s personal and professional lives. In order to do his job, he must earn their interviews and try to belong in their community. However, the more he spends time in the woods, the more he understands why people would want to separate themselves from the outside world and start again. I was lucky enough to talk to Mattie over Zoom about her own immersion into the world of Simplicity, her research into cults, and the labor of building a world where everyone can feel safe.

Lara Boyle: Can I ask about the Stephen Sondheim quote that you use in the epigraph because I hadn’t heard of the musical it’s from, but I was curious about the influence of Stephen Sondheim on your work?

Mattie Lubchansky: Yeah, so, I think I was going back and forth from that quote and a quote from Into The Woods, which obviously is a little bit more obvious. It’s a lot of people wandering around the woods lost and not knowing what to do, even if they get what they want, right? But Pacific Overtures is a show I’ve never seen staged, but I’ve listened to it a lot. And the show is not even my favorite Sondheim show, but that song is my favorite Sondheim song. . . And the song is kind of about how history is this unknowable thing and how it is subject to both like intent by humans politically but also the past is this foreign country that we can never get a handle on, we can never know what the objective fact of a thing even if you were there to observe it, and now all this stuff happens because people are there and people are observing it and the idea that, like the idea, like the quote in the book, it’s the ripple not the sea, not the garden but the stone. It’s not the building but the beam. It’s all these tiny pieces, and I wanted that to kind of hang over the book, and they had all this stuff about museums in there as well.

Lara Boyle: Nice. Were there other epigraphs that you were between?

Mattie Lubchansky: It was just that one and something from No One Is Alone from Into The Woods which I deemed too corny.

Lara Boyle: Do you find yourself being influenced by other forms of literature and art for your comics, like besides the world of graphic novels?

Mattie Lubchansky: I actually try, when I’m working on a new book, I kind of shut myself off from reading comics. I’m inspired constantly by many of my colleagues, and I love to go to comic shows and go spend a couple hundred dollars and like lose myself in the last year or two of work or I don’t really like read that many comics like day to day when I’m working on a new thing because I don’t want to be ripping anybody off. I try to draw very eclectically in terms of influence. Like this book, it was a lot of horror movies and specifically The Wickerman, which I think is an obvious sort of draw for that, but also a bunch of like, I was thinking a lot about Henry Sellick’s Stop Motion work. I listened to a lot of music and musicals when I’m writing. And I also, when I’m working on a fiction book, I tend to be reading a lot of nonfiction while I’m doing it. I try to draw from history and like the kinds of things I’m interested in outside of fiction, try to transmute all the stuff I’ve been thinking about into the work.

Lara Boyle: It felt like there was this element of psychological horror in this one as well, and this build up of existential dread throughout the book. How do you go about building the world and creating that lead in so it gets more and more tense throughout? I’m not a horror fan, so I’m not like, well-versed in horror, but I love this book, and I also love that there are queer protagonists that get to just be queer protagonists. But I’m always interested in how you design a whole world coming from a nonfiction writer’s perspective, and how that process is.

Mattie Lubchansky: Yeah, so for me it was sort of with this book, in the past I’ve sort of, like, well, I had the plot already settled, um, and, like, I was kind of, like, looking for characters to fill in the world. With this one, the first thing that ever came to me was that first vision that Lucius has where he has that erotic encounter with that big green-like deer creature, that was the first thing I had for this book. It kind of came to me fully formed, like that sequence. I was in upstate New York in a hammock in the woods, and I was sort of, like, half asleep, and this thing came to me, and I was, like, who’s this gentleman? Which is not normally how I work. Which is I think responsible for the sort of dreamy quality of a lot of this book, was like me trying to work through this weird dream that I had.

So a lot of it was filling out the details around, like, this person who I had a sense of, this is someone closed off to his own sexuality in a way. So I wanted there to be this place that is so free around him. I wanted the place he came from to be as constricted as possible. Or at least constricted in an interesting way to me in terms of being watched and constrained physically in a place. And so I got to the walled city, and I started thinking about how would you get there? What happened to America that this is what it looks like now?

And so I started building off from there, and the building of the world of Simplicity the town and the sort of pseudo religion they have going on, and their sort of utopian commune, that was when I got really into doing research about these 19th century pre-Marxist utopian millenarian communes that were all over New York and Pennsylvania and Ohio in the late 1800’s. Specifically, the groups that I got really obsessed with while I was writing this were The Shakers, who most people have heard of, but we all kind of know about the chairs and that they didn’t have sex. But there’s less about in terms of the popular imagination of the Shakers is that they were the shaking quakers. At services, they would rip off their clothes and run around nude in the woods and get their ya ya’s out because there was no other release in their lives because it was such a peaceful quiet. It was illegal to be horny. And then the other group that I really drew a lot from was this group of mostly like French artisans and middle-class French people that were all fans of this book called Travels in Icaria from this philosopher called Étienne Cabet. The book Travels in Icaria, much like the book in my book, is like a travelogue about a fake place called Icaria and all these French people, basically, they came to America, and they kept trying to build the utopia from the book. They tried in Louisiana, they tried it in Texas, they worked for awhile in Naveou, Illinois, which is a town that the Mormons built and abandoned, and these other people showed up and tried to build their utopia there. But I was just really fascinated by this idea that, oh, I read this in a book, so I’m going to make it in real life. All these people around this time, their idea was, “Oh, I’m going to go start a town and we’re going to see how good our town works and then back in the world, everybody would see how great their commune was and reorder society to be more like it.”

And like to me, that is like a complete misunderstanding of how power is and how power functions and how ideas are propagated and how change occurs, but it is a sort of explicable feeling that I think now we also get, as queer people, if you’re a trans person, you know somebody that knows somebody that knows somebody that has started a farm, somewhere to be like me and five other girls are going to raise goats, and I was trying to understand this separatist impulse, which to me I was trying not to come at it from a judgmental place. I think by the time I was done writing, I was not feeling judgy about it, I was kind of at the beginning, but I was trying to understand this impulse of like why do you go do this, and I think so much of it is back then, and also again in the 60’s and 70’s where you saw a lot of this kind of behavior, and now, for queer people specifically, it feels like the world is ending, and you’re like, well I am completely alienated from, I have no control over the material circumstances of my life right now, so what I will do is go somewhere small where I can exert a certain amount of control over my environment, in a way that is a little simpler than martialling hundreds of thousands or millions of people to storm the White House. And back then, the communes I was really obsessed with it, to them was the invention of Capitalism, like everything being commodified, everything being moved from this largely agrarian world that people lived in previously to manufacturing jobs, to urban life, everything felt like it was slipping away from people and they didn’t know what to do and they felt scared and they thought the world was going to end and they thought like the millennium was approaching, the thousand years of peace when the Golden Cube of New Jerusalem will descend from heaven and land on Earth and they all live there with Jesus. They thought that was going to happen because their jobs looked different very suddenly, and their whole lives were reordered, and I was just trying to get to the bottom of this feeling, and like, what do you do with that?

Lara Boyle: One of the most compelling parts for me with the book was that at the beginning, Lucius does seem very judgmental coming from an outsider’s perspective of the commune, but towards the end, he’s kind of understanding their perspective and kind of gets engrossed in it. Did that help you process these kinds of questions through the book?

Mattie Lubchansky: Yeah, I certainly got more sympathetic to, like, you know what’s really good is community, and this sort of thing is like, not to spoil the book or whatever, but the idea that, on some level, Amity, the people in the commune, have to understand that you can go make a perfect society in the woods for you and a hundred friends, but this is not what the book is about. There’s a different example, but that won’t stop global warming from destroying your crops. Like the world is still there and you are still a part of it, and I think this is like, trying to synthesize these ideas, but you do kind of need this community building for like, sounds so corny to phrase it like this, but for the revolution to occur, right? You have to start with your neighborhood. There’s no way to get people to, not like everyone has to be best friends, but you have to understand that you live in a society first, and there’s sort of like a synthesis of these ideas that I sort of arrived at as I wrote the thing.

Lara Boyle: Did you find any research on the relationship between queer people and communes? Has that ever been a historic link, or was that your way of exploring a new possibility where that might have happened?

Lara Boyle: It’s pretty easy to understand why gay people and trans people would want to go live apart from a society that hates us, like, it’s a very explicable impulse, and, like, you know, the Hudson Valley is still littered with the remnants of all these queer separatist groups out there, but I tried to sort of, like, the book takes place in the 2080s, and in the history of the book, the group left in the 1970s to start this thing. And I was trying to extrapolate what would a 1970s understanding of sex and gender and queerness, all that, if you left that alone for a hundred years, what would get cooked up?

Lara Boyle: Was the supernatural element a way to explore that alienation? Because we don’t get super easy answers on that in the book, so can I ask how you conceptualize the role of the supernatural or the visions with the monsters?

Mattie Lubchansky: Yeah. So the monsters that are in the visions, there’s one good one and one bad one. Sort of like to me, they were originally conceived of as the warring factions of Lucius’s brain and body. One of them is just this big sexy thing that he likes to have sex with and sort of like, this is like the freedom of joining up with this commune and being outside the city and he’s so buttoned up sexually in a way that is interesting because as a trans person, you do have to do so much interrogation of yourself, and you do have to be in touch with your body on some level, but then there’s this other hurdle that some of us face that now I have to like rank in with being in my body again, and it doesn’t solve every problem you have. So this freedom for him is sort of represented in this one creature. And then the other one is sort of like the doubt in the back of his head, like the fear and the shame, and he comes from this place that’s all surveillance, and it’s not a coincidence that it’s a big eyeball with mouths there to devour him living just under the surface of the thing that he wants and desires. And to me, there’s sort of like, I don’t have a definitive answer on whether or not they are real. Like you never see their effects in the real world, except one time you kind of do. And to me, that was sort of like, I think it was just sort of like this person sorting through their feelings in a way that in their waking life he can’t possibly come to terms with any of his own feelings, and this was just him cracking under some amount of pressure from himself.

Lara Boyle: What does your process look like when you get the first idea? How many years does that take you, and do you start with the visuals or the writing or the plot?

Mattie Lubchansky: There are smarter people than me to talk about this, but every time you write a book, you have to learn how to write a book. Every book is different and teaches you how to write it as you do it, and by the time you’re done with it, you’re like Oh great, now I know how to write a book and you go to write the next one, and you’re like I don’t know a goddamn thing. But this one was very much, yeah, I was doing all this research, I have an idea, and then I was like I think I want to do something about cults and communes and I was talking to a friend of mine who recommended a book about these communes in the 1900’s called Paradise Now, which I shouted out in the acknowledgements because it was very important to the research of this thing, and then. Once I had sort of like, I started reading this book, and for a long time, like months and months and months, I was just, you know, I like to apply the take a walk method where I’m just reading. I was just writing a lot of sentences. Is this idea a book? Does this go into the book? Is this a book style idea? And I started doing that for awhile, and after like six months of this, I had a 30 or 40 page Google Doc that was just sentences. Like most of it was gobbly gook. And then I gave that a month or two off, and I went and read it again, and I culled it down until I had, like, okay, here’s the five ideas I want the book to be about. And here’s a bunch of little details from all these societies that I was obsessed with, and New York history, and all this other stuff, and my personal experience with working in museums in a former life, and I was sort of like, okay, I got the meat of what I want to do. And then I do a lot of you know, comics are so labour intensive that, like, every step, I want to get it as edited as early as possible, just because I hate redrawing things, I would rather everything be really cut and dry before I’m inking. So I outline really, really heavily. The pitch for this book that I sent to my editor was like, you know, an outline chapter by chapter, down to individual conversations people were having, not the dialogue of the conversations, but so and so talks to so and so, and they determine that this thing happens. I had everything really really, really built out that way, and then it goes for me pacing is so important, well I have, this book is about 290 pages or something, and I want ten pages, I want this to take up ten pages, so okay I’ll break this down into ten pages and I’ll write the script that way. I script the whole thing, and then I pencil the whole thing, and then I color the whole thing.

Lara Boyle: Do you take the sentences that you had and put them into the script?

Mattie Lubchansky: Yeah, I mean, I try to write as as much of a stream of consciousness as possible. I find it so much easier to edit. I try to get the first draft down as dirty and as awful as possible and then, but not the whole thing. I need to get like, I need to write a twenty-page chunk in a day. And then I’ll edit it tomorrow and fix it then. But I just need to get it out for me.

Lara Boyle: Do you have a drawing routine that you do, or do you go with the flow more?

Mattie Lubchansky: I go with the flow. So the one psycho thing I do is I don’t thumbnail. By design. I just hate it. Like extremely. I don’t like doing it. I find it really tedious. When I’m writing, I try to make my scripts as detailed as possible, and I put in panel breakdowns and layouts, and I have a thumbnail in my brain when I’m writing the script, then when I’m pencilling, I just pencil really slowly. I like thumbnailing while I pencil, which is probably not the most efficient way to work, but it’s just the way that I work, and my drawing routine is like, I have to do the whole thing all the way through. I have to pencil the whole thing first, and ink the whole thing, and then I speed up as I go. I can ink way more pages in a day than I can pencil. So I’ve been working on another book right now, and I’ve been pencilling since this Spring, I’ll be pencilling into February, like a year of my life just pencilling, that’s gotta be a little crazy. It especially drives me crazy when I’m coloring because it’s so, I find it very tedious. But for me, I can’t wait until I’m inking, it’s my favorite thing to do, I find it so sort of like soothing, I can like watch a movie.

Lara Boyle: That makes me feel better with the thumbnailing. Because I tried to thumbnail, I did about thirty of them and I gave up and just started doing it as I make the comic, so I feel better about that, because I was told that was like, an art crime to not thumbnail.

Mattie Lubchansky: I mean, the thing about comics is there’s not a correct way to do it. Like whatever works, whatever gets you to a finished product that you’re happy with, like the method, like I was working on some project, maybe it was for Silver Sprocket, I was like, I’m gonna thumbnail this one, because it’s short, and like, I want to get a handle on it, and I bought a little tiny notebook and I was like this is going to be the thumbnails for this book. I think I got ten pages in, and I was just like this fucking sucks. I don’t know. I just stopped. It just wasn’t adding anything to the process. I wasn’t having any discovery there. And I think, early on in the process, if it’s not adding anything, it’s just repeating what I’ve already done early on in the script, so I was like, well, there’s no point to this.

Lara Boyle: Do you have something you hate to draw when you have to draw it?

Mattie Lubchansky: Ooh. It really depends. Like I did, my first book for Pantheon, Boys Weekend, all buildings, with places like a fake sea setting Las Vegas, and it’s all futuristic buildings. And by the end of it, I just hated drawing the landscapes so much. Because I was sick of drawing windows. And then the city collapses by the end of the book. And I was just, the destruction of building, I was like I can’t draw this anymore. Have you ever read Akira?

Lara Boyle: I have not.

Mattie Lubchansky: Akira’s in six volumes. And one of the volumes is just buildings exploding. Several hundred pages. And it’s like this guy just drew buildings exploding for like a year of his life. Like, I was drawing buildings exploding for like a month, and I was like, I’m ready to end it all. And I was like, really sick of building, so, okay, next book is gonna be in nature. I don’t wanna draw buildings anymore. So I draw Simplicity, and it’s all trees, and, by the end of the book, I was like, if I have to draw another tree, I’m gonna quit comics. So the next book is like buildings again. So just like, I think it comes out, I really hate drawing backgrounds. I got into drawing because I love drawing faces. I love drawing people moving. I love someone in motion. I can just draw people all day. I’m too much of a control freak to ever do it, the manga style where you have someone draw your backgrounds, is so enticing to me, because I’m not as interested in things.

Lara Boyle: When did you first get into comics, and what made you interested in comics?

Mattie Lubchansky: I was a kid. I was really into newspaper comics when I was a little little kid. I was really into The Far Side.

Lara Boyle: I’ve never read that one.

Mattie Lubchansky: You should. I have a tattoo of the lady from it. She’s really important to me. The Far Side is great. It’s like single-panel strips, I’m a thousand years old I guess, so that’s fine, but it’s really good. It ran in a newspaper, I was obsessed with it. I did unironically love Garfield as a child, and I had all the Garfield collections. I was weirdly into Dilbert as a child and then the other thing, that was a really big inspiration to me was the comic Life in Hell.

Lara Boyle: That’s by The Simpsons’ creator, right?

Mattie Lubchansky: Yep. Matt Groening’s underground, weekly comic that is so funny, and I think I was 13 or 14 and my mom bought me one of the collections. She was like I saw this and I thought you might like it because I know you like The Simpsons. So I read it, and I got obsessed with it, and I bought all of the collections, and I read and reread them. And then at this time also I got into early webcomics, I was reading about comics in like 1998. As a young child. And later I got into longer graphic novels. Probably one of the first graphic novels I read was Watchmen. Probably. But I was never really into superhero stuff. My taste just sort of spiralled out from there. It was really strips, is what got me into comics. Which is still where I cut my teeth as an artist too. Like drawing short form strips. Which carries over a little bit. My sense of timing is still very page to page. I try to tell as much of a little story as I can. I try to eliminate as much dialogue as possible, which is comic strip world, the perfect comic strip is no dialogue at all, you know, so I kind of try to be as efficient in my storytelling because the most you can get into a panel is a sentence.

Lara Boyle: Do you still pull inspiration from strips, and do you do research into the strips as like visual research?

Mattie Lubchansky: I still read a lot of comic strips, like stuff online. I still do a weekly strip. And I’ve been doing it every week for like, seventeen years now. But like I’ve just been doing that forever, so that rhythm just sort of lives in my bones in a way that I can’t ever shake, even if I wanted to I think.

Lara Boyle: If you had any advice for cartoonists, what would it be?

Mattie Lubchansky: For me, my sort of like stock advice, when people ask me about getting started, or like being younger, trying to get into it, or whatever, it’s always like, the thing I wish someone had told me was to just sort of like, if you want to make longer form work like books, which is what I always wanted to do, it took me a long time to start doing it, is to just start and finish something. Like don’t start with your thousand-page opus for Webtoon. You can feel it out, but it’s gonna take a really long time. Do a minicomic. Start short, and then the longer work will happen eventually. But just, like, comics are so hard, and I feel, I’ve been doing them now for close to twenty years, it’s been my full time job for over a decade, and I feel like I’m just starting to maybe kind of get good. It’s so hard, it sucks so bad, you gotta really love it. I feel like it’s so important to me to just get the pages in. Just draw the pages. Don’t stress too much about everything being perfect or everything being for the consumption of other people. Just like, make the work. Start and finish small projects. Show it to other people. Get like compatriots and comrades. And people you like to share your work with. And you’ll make each other better and I feel like that community is really important. Yeah, minicomics, man, that’s the way to go.

Lara Boyle: Thank you so much.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply