I met my first comic book embarrassingly late. No long boxes, no prized issues, no childhood nostalgia, nothing. Then I took a “History of Comics” class in college because I needed one more credit, and suddenly I was holding a piece of brittle pulp that felt more like an artifact than a story. The cover was sun-faded, the staples rusting. It had clearly lived a life before I touched it, and that surprised me. I’d never thought of comics as objects with histories, with scars, with their own kind of gravity. That moment opened a door I didn’t know I was looking for.

What struck me wasn’t the superhero on the front but the material of the thing, the way the paper felt soft at the edges, almost velvety from being handled so many times. Someone had read this comic until the pages loosened. Someone else had kept it. Now I was adding myself to that chain. It made me wonder why certain objects survive when so many others disappear, and why people fight so hard to protect the fragile things that weren’t made to last.

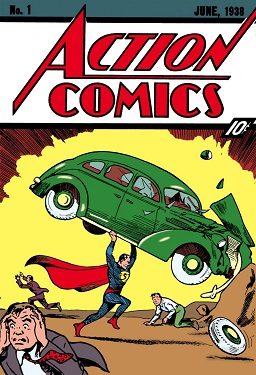

Because if comics have a secret truth, it’s this: they were never supposed to survive. They were printed fast and cheap on paper that practically disintegrated on sight. Conservators describe early comic stock as “inherently unstable,” full of acidic lignin that darkens and crumbles with age. The industry counted on this. Comics were churned out for kids who’d roll them, tear them, trade them, forget them. The idea that anyone would save one, let alone frame it, would’ve sounded ridiculous in 1938.

And yet people kept them anyway.

Part of that is scarcity. During World War II, millions of comics went into paper drives or were read to pieces in barracks. The survivors became accidental treasures. But scarcity doesn’t explain the affection people developed for them. That came from somewhere else: from the way comics lived in the world, passing through hands and pockets, absorbing fingerprints and sunlight and small, private moments. They weren’t built to be artifacts, but they became ones because readers treated them that way.

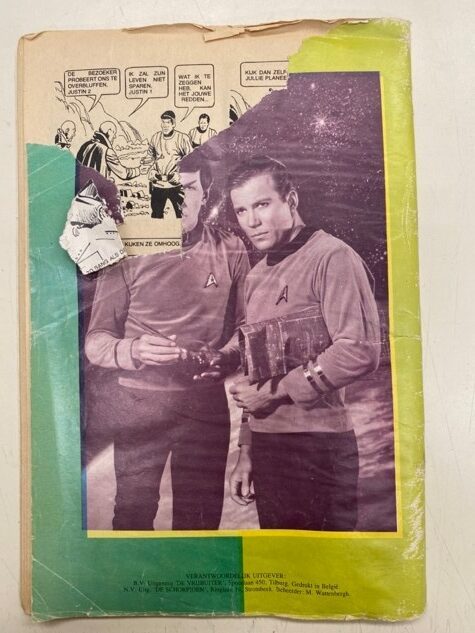

What fascinates me is how the first real archivists weren’t museums; they were fans. Long before institutions cared, collectors were sealing issues in plastic bags and sliding acid-free boards behind them. They built personal archives in basements and spare rooms, places that doubled as time capsules of their own pasts. These weren’t sterile, climate-controlled spaces; they were lived-in, cluttered, and entirely human. Yet the motive behind the sealing and sorting was the same impulse that drives museum work: don’t let this disappear.

By the time the Smithsonian and the Library of Congress started building comic collections, the fans had already done decades of groundwork. They figured out how to store fragile pulp, how to avoid sunlight damage, and how to flatten a warped cover without tearing the spine. They learned by doing, by ruining a few issues along the way. And in that trial and error, they unintentionally created a preservation culture, one that blended nostalgia with responsibility.

Institutional archives eventually recognized the value of what collectors had been doing all along. They began storing early issues flat, in dark, carefully monitored boxes. Conservators talked about humidity the way gardeners talk about soil. Displaying a comic required calculations about light exposure and pigment sensitivity. Museums adopted a “lightest touch” approach, repairing a torn page just enough to stabilize it but never enough to erase its history. The idea wasn’t to make a comic look new; it was to let it be old safely.

And this is where comics become more than entertainment, they become mirrors of the people who held onto them. Every crease is a reminder of the hands that turned the page. Every faded corner reveals how someone read it, maybe outside on a porch, maybe under a lamp at midnight. These imperfections aren’t flaws; they’re witness marks. They turn mass-produced pulp into personal archaeology.

I think that’s why digitization, for all its benefits, feels a little conflicted. On one hand, digital archives are a miracle. Readers can open an app and find thousands of issues once scattered, rare, or too expensive for anyone but die-hard collectors. Stories that lived in basements or high-security vaults suddenly appear on glowing screens everywhere. Digitization democratizes access. It transforms rare comics into public property. Anyone can read a Golden Age Superman story without handling a single fragile page.

But something disappears in the translation. A digital comic doesn’t sag at the staples. It doesn’t smell like old paper. It doesn’t warm in your hands or crackle faintly when you turn it. You lose the sense that the comic has lived a life. On a screen, every issue feels equally smooth, equally bright, equally weightless, all the bruises of time sanded away. The comic becomes pure content, detached from the world that created it.

That’s not a bad thing. It’s just different. Digital access saves stories that might otherwise vanish. But physical comics save something deeper: context. Not just the narrative on the page but the narrative of the object. Who held it. Where it traveled. Why it was kept. A comic is never just a comic. It’s a piece of someone’s past, a small relic of lived culture. When you pick one up, you can almost feel the decades vibrating faintly through it.

This is why comics make such powerful vessels of memory. They are worn down not by neglect but by love. They are saved not because they were expensive or prestigious, but because someone felt an attachment strong enough to imagine a future reader. Comics are, in many ways, the most democratic artifacts we preserve. They weren’t made for elites; they were made for everyone. Their survival is a testament to how everyday people, kids, fans, collectors, shape cultural memory just as much as institutions do.

When I think about that first comic I held, the one I touched so late in life, I remember the small jolt of recognition I felt, not just of the character on the cover, but of the object itself, tired and alive at the same time. I wasn’t just holding a story. I was holding all the hands that came before mine.

That’s why people put comics in plastic sleeves. It isn’t about money or rarity or even nostalgia alone. It’s about the belief that some things, even fragile things, deserve to outlast us. Comics weren’t built for longevity, but their readers gave it to them anyway. In that sense, every preserved issue is a quiet act of resistance against forgetting.

What survives tells us who we were. And in the brittle, yellowed pages of old comics, we find not just heroes and villains, but evidence of a culture learning, slowly, imperfectly, to honor the ordinary objects that shaped its imagination.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply