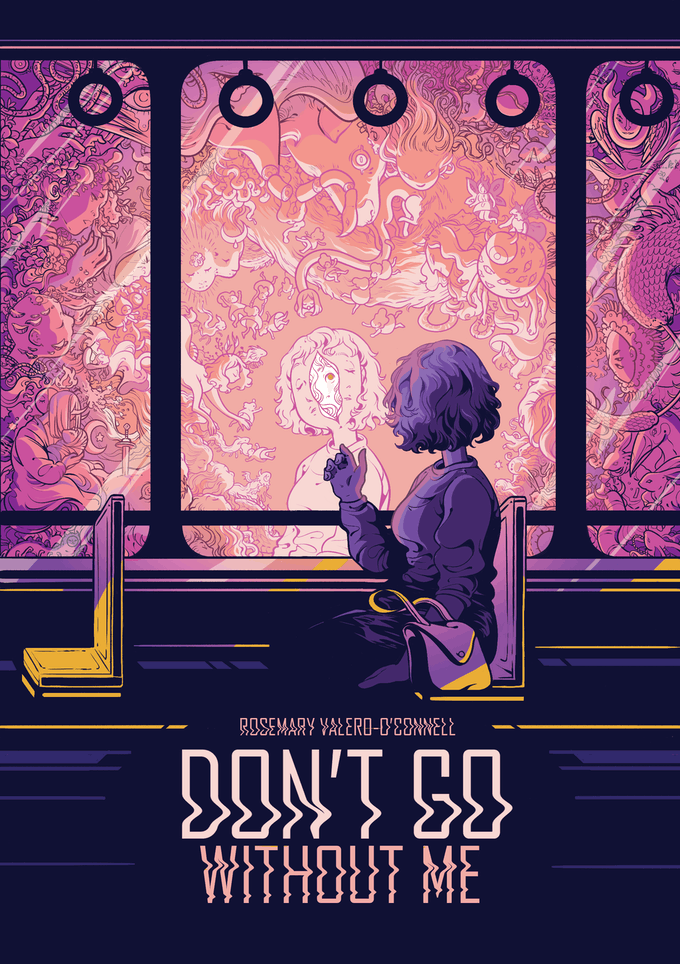

Rosemary Valero-O’Connell’s Don’t Go Without Me represents not a sophomore slump as much as a slouch. The showpiece in the collection, “What Is Left”, still dazzles, as it did when it received two Eisner Award nominations in 2018 for best coloring and best single issue/one-shot. Its periwinkle and pink meditation on memory, life, and death displays a ferocious intellect and the sort of humanism that’s always in short supply. Don’t Go Without Me reissues “What Is Left” in a more robust form than the original mini-comic. This go-round it arrives with a gold embossed cover, french flaps, and the additional stories: “Don’t Go Without M”’ and “Con Temor, Con Ternura”. Neither of these two new offerings reaches the high standard set by “What Is Left”, a tall order even for a talent like Valero-O’Connell. Instead, she offers stories that serve to buttress her masterwork like the supporting panels to a triptych of loss, love, and hope.

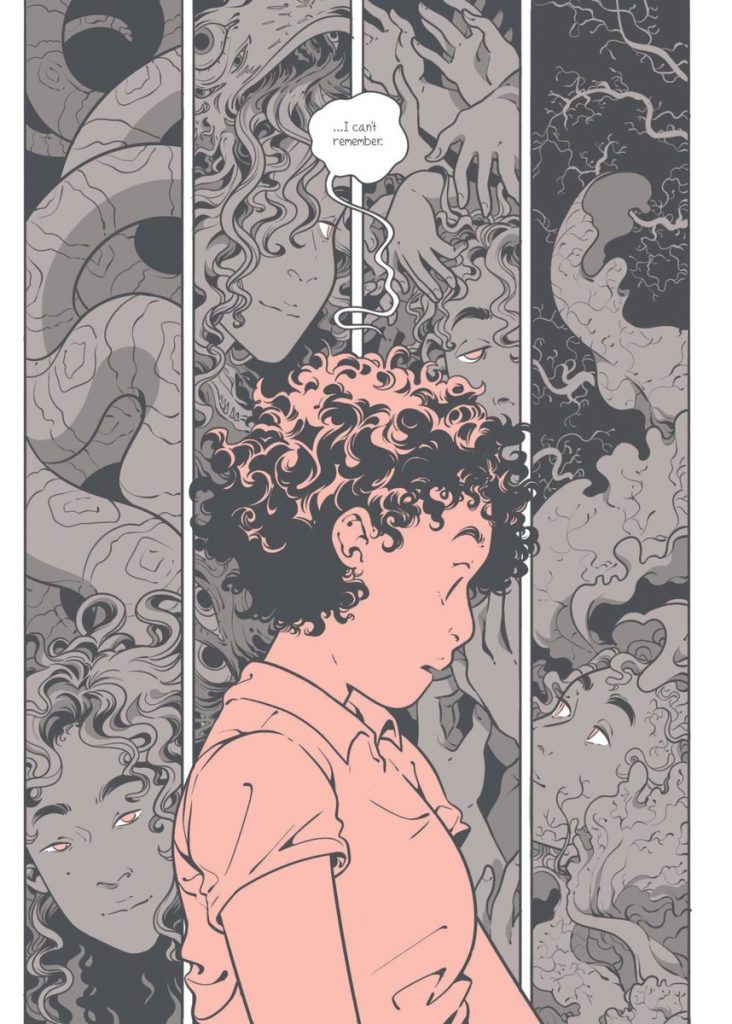

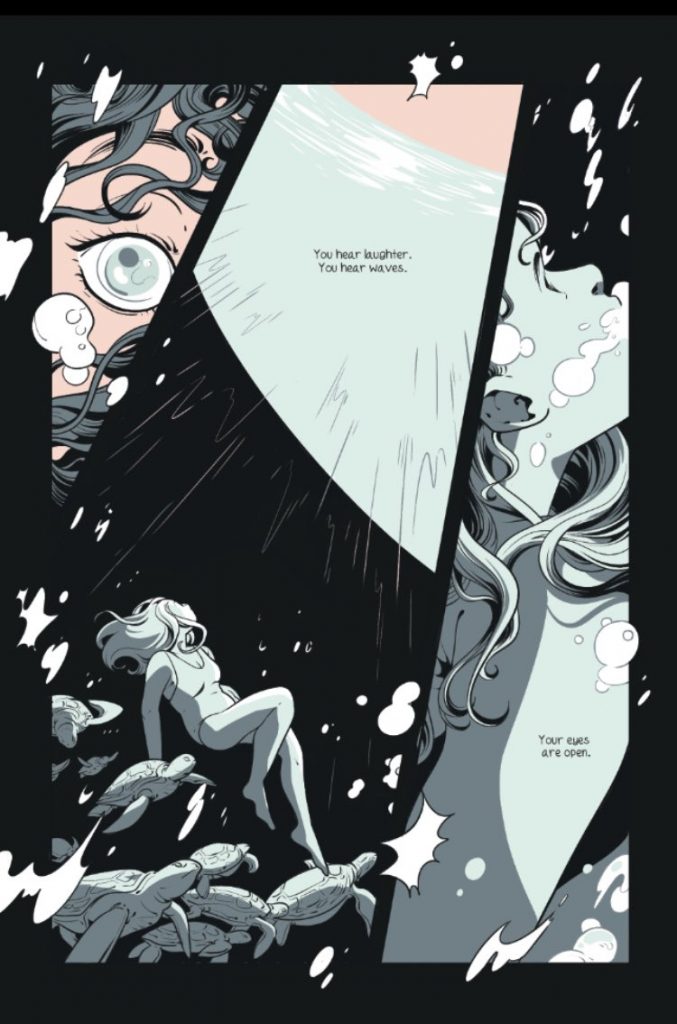

Besides some work-for-hire assignments and a star turn as the illustrator of the Mariko Tamaki-penned graphic novel, Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up with Me, for which she won an Ignatz award for Outstanding Artist, Valero-O’Connell is firmly in the “arrow going up” stage of her career. Don’t Go Without Me burnishes her reputation as a stubbornly open-ended storyteller fascinated by loss and how to fill the gaps therein. Counter to these absences are pages overflowing with the presence of ink and lines, lines, lines — so precise is Valero-O’Connell’s cartooning to call it “pretty” denies its approach to the sublime. Like the manga she clearly adores and is influenced by, she is an exacting cartoonist. Rarely does she draw a head of hair that’s not tastefully tousled or a background she doesn’t stuff with stuff. In all the floridness and fluidity of her art, in all that is present (and absent), though, something remains missing. Valero-O’Connell’s characters are cerebral, navel-gazers to a fault. That’s the point in “What Is Left,” yet this becomes somewhat problematic in “Don’t Go Without Me” and ‘Con Temor, Con Ternura.” In these stories, intellectual and emotional intimacy eclipses physical intimacy — as if love is ever courtly and never consummated. Perhaps Valero-O’Connell is the cartoonist of these socially-distanced days.

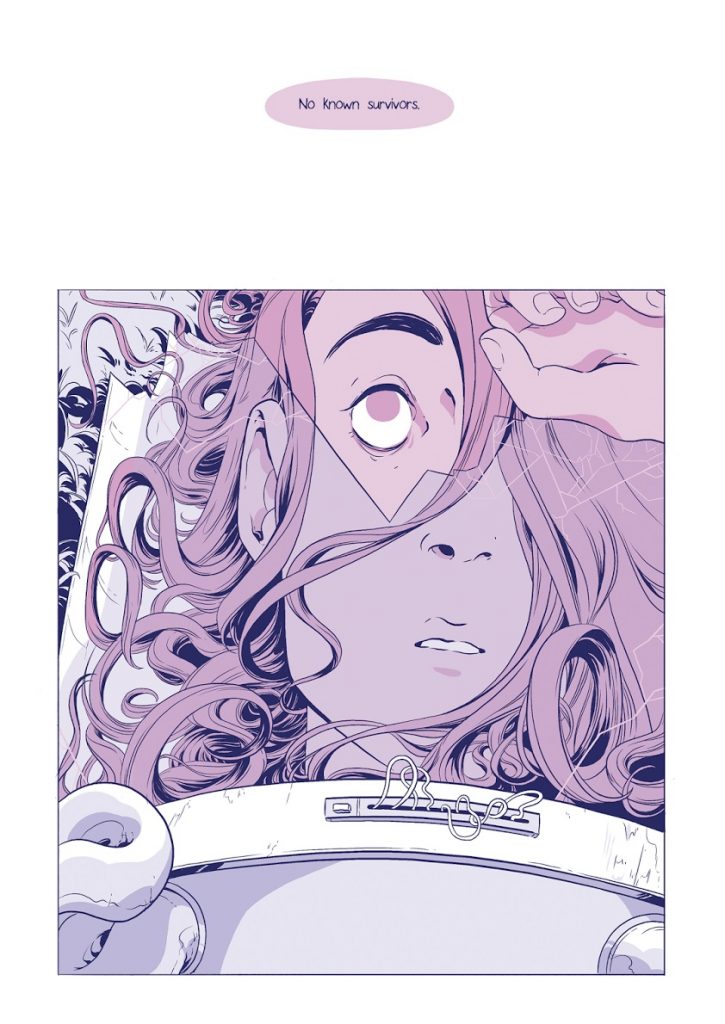

“What Is Left” sets a sole survivor, Isla, an adrift astronaut, alone in the remains of a spaceship as it runs low on its fuel source, the power of memories. “Everyone I’ve ever loved pulling us through the stars,” says the source, a fellow crew member, Kelo, who is now only a memory herself, if she ever was anything (anyone) else. Kelo’s absent presence allows Isla to contemplate the power of memory, literally, along with its slipperiness and fluidity. Valero-O’Connell weaves Kelo’s life into the story in such a deft way she makes the reader forget that “What Is Left” is a solo act. Kelo is dead. Isla is alive — she is what is left. Isla experiences Kelo’s soul displaced from its body, the physical is forfeit and so too Isla’s connection to the flesh and blood of others. Because Isla is alone, it’s all internal; the external is inconsequential, a permanent impermanent.

Isla has nothing to lose, except herself. Likewise, “Don’t Go Without Me” plays on the same separation, but it adds the anxiety of lost love or not. An unnamed female narrator travels to a parallel world and is immediately separated from her lover, Almendra. The narrator spends the rest of her time in the company of fantastic creatures, exchanging stories to aid her search to find “Al.” The more she persists in her quest, though, the more she forgets. Memories in “Don’t Go Without Me” (unlike in “What Is Left”) aren’t power, they’re currency, but all they buy is absence. The narrator does find someone, but due to her own anonymity and her inability to remember Almendra — or if there ever was an Almendra — the impact is far less than poor Isla wondering if she’s going to die in deep space, unloved and forgotten. The person the unnamed narrator finds is the only other human in this world of Lynchian dream creatures. If it is Almendra, it doesn’t matter. Perhaps finding someone/anyone is the goal and so the who, where, and how is ephemeral and only needs to last as long as the search itself. If the unnamed narrator had a name it wouldn’t change much because Valero-O’Connell never establishes the relationship between the women prior to the narrator’s journey. There is one panel of two women lying abed likening the counterpart world to an “egg” or layered “transparencies.” Is it the narrator and Almendra? Does it matter? The reader is told by the narrator that there’s an Almendra and that the narrator is in love with her, but it’s the narrator’s idealized version of her lover: a memory and not a physical being. Haebeas amans.

Don’t Go Without Me ends with comics poetry, “Con Temor, Con Ternura.” If “Don’t Go Without Me” deals with the anxiety of loss, “Con Temor, Con Ternura” deals with the fear (temor) of what’s to come and the choice to confront that fear with tenderness (tenura). It’s filled with binary noodlings: “What will you do if it wakes up? / What will you do if it doesn’t?” And “When will it wake? / “What will happen when it does?” The”‘it” in question is a giant woman who sleeps in the sea. And yes, her hair is so perfectly imperfect it hurts. This “sleeping colossus” is symbolic of any force majeure: natural disasters, global pandemics, etc. Families, lovers, and the curious gather at the seaside. There is food and drink, dancing and music, passionate embraces and quiet moments—a danse macabre for the emotionally intelligent. Valero-O’Connell cares little if Checkov’s giant wakes up. Her interest is in how one lives in the moments leading up to the moment regardless if it happens or not.

Do you choose to be present, in the moment, an astronaut lost in space, a lover alone, a world at end, a boat against the current; and (only) kindness as your shield? Or not? For Valero-O’Connell the question, the suggestion, is answer enough.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply