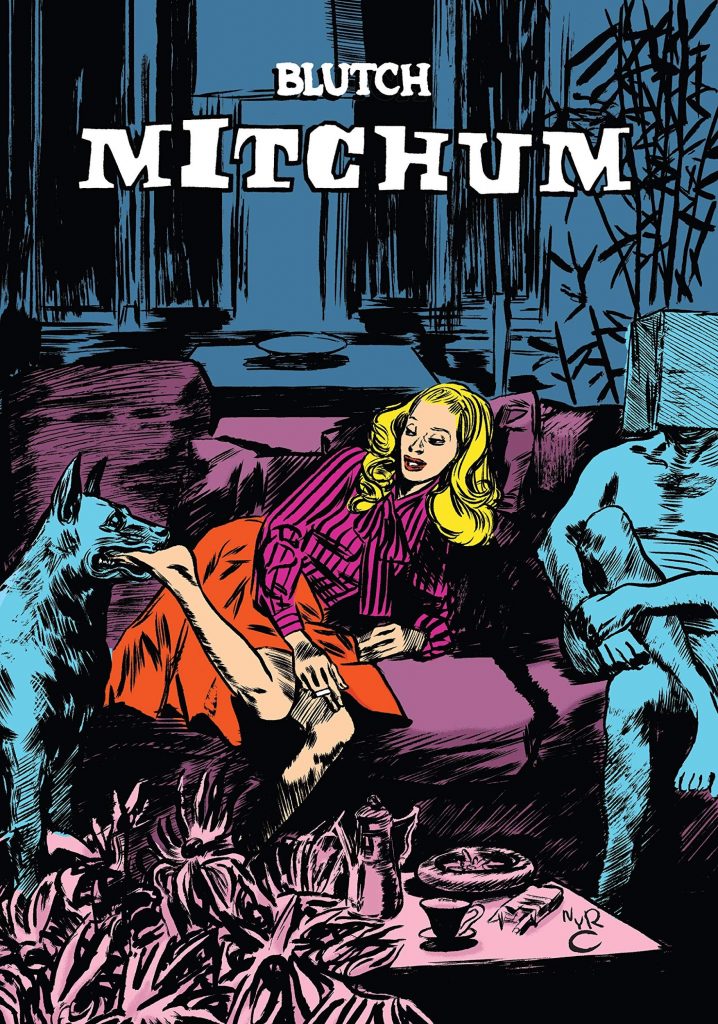

Absolute artistic freedom is a rare thing to come by and not to be taken lightly, much less for granted, so it’s to his credit that legendary French cartoonist Blutch made the most of it with his five discrete, but thematically-linked, Numero publications issued by Editions Corenlius from the mid-to-late-1990s. Later collected into a single volume entitled Mitchum, the fine curatorial staff at New York Review Comics has now seen fit to release it in English, complete with the top-notch production values we’ve come to expect from the imprint and a fair number of additional pages, as well. It’s safe to say that this represents the work in its most comprehensive, “finished” form, and it likely comes as no surprise that it’s absolutely gorgeous — even when it’s absolutely ugly, even brutal.

There’s a real sense of throwing a lot of ideas at the wall to see what sticks here — and of boldly forging ahead even when some of it doesn’t — and that’s going to lead to an uneven experience by definition, but it’s to Blutch’s credit that even his “lows” aren’t actually very low, while his “highs” are often downright exhilarating. Whatever he could pluck out of the ether — or maybe the word should be zeigeist — and construct a visual narrative around and/or out of, he did, and, more often than not, this lends to these proceedings the quality of something halfway between a stream-of-consciousness rumination and a from-the-gut visual treatise, all expressed with force, clarity, and a breathtaking commitment to a damn-the-torpedoes impact that seldom fails to impress at a core level. Odds are pretty good, then, that if you appreciate the comics medium, you’ll like this book a lot, even when it takes you to places you’re not necessarily prepared to go.

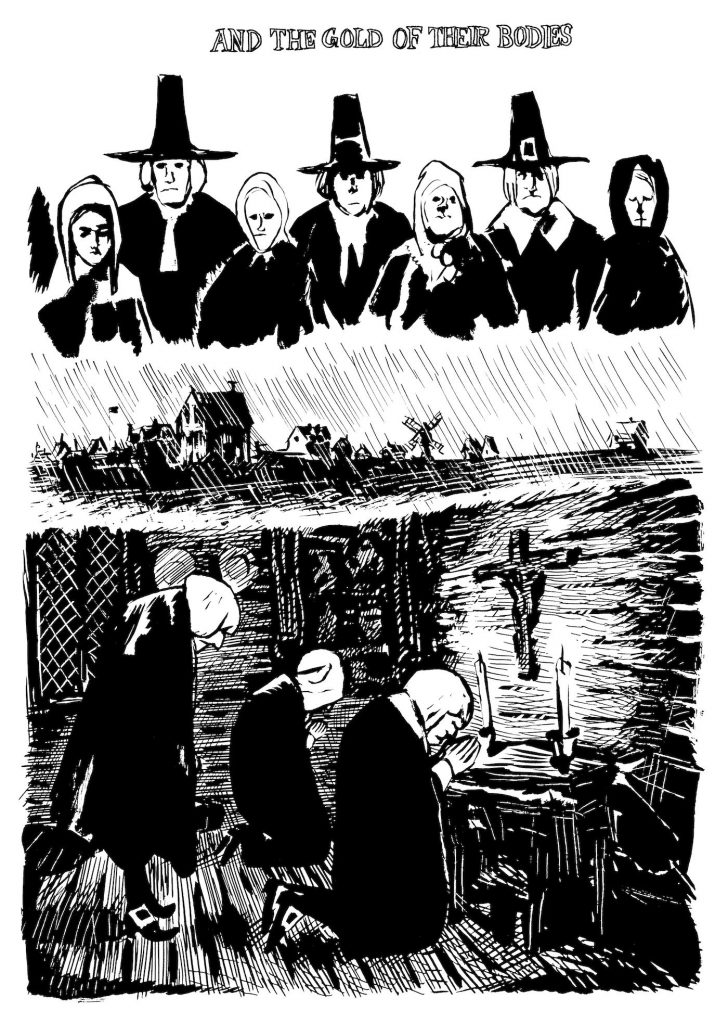

Dancing figures are a constant motif throughout — presented either in the form of couples, or women dancing solo — but even when they’re absent from a given page or sequence, there is something of a balletic quality to the interplay between the various characters, rendered with fluid black inks that often appear to move up from the bottom of a panel and spread themselves throughout in naturalistic, if borderline-anarchic, fashion. This marks a stark contrast to the woodcut-influenced imagery of puritanical colonial America that Blutch renders as the soul-crushing nightmare of sobriety that it no doubt was, but constraining and/or outright devouring the feminine principle is a theme he returns to again and again, whether it’s brought to the fore via women subjected to strict and pious prayer regiments, monstrous creatures observing a lithe dancer and then unconvincingly appropriating her movements after apparently killing, possibly even ingesting her, or a time-and-shape-shifting Robert Mitchum (hence the book’s title) engaging in a violent confrontation with a female kick-ass action hero who sure looks a hell of a lot like Coffy – and Foxy Brown-era Pam Grier — after he’s brutally attacked another lady without Pam’s street-smarts and fighting skills. Woman in chains, indeed.

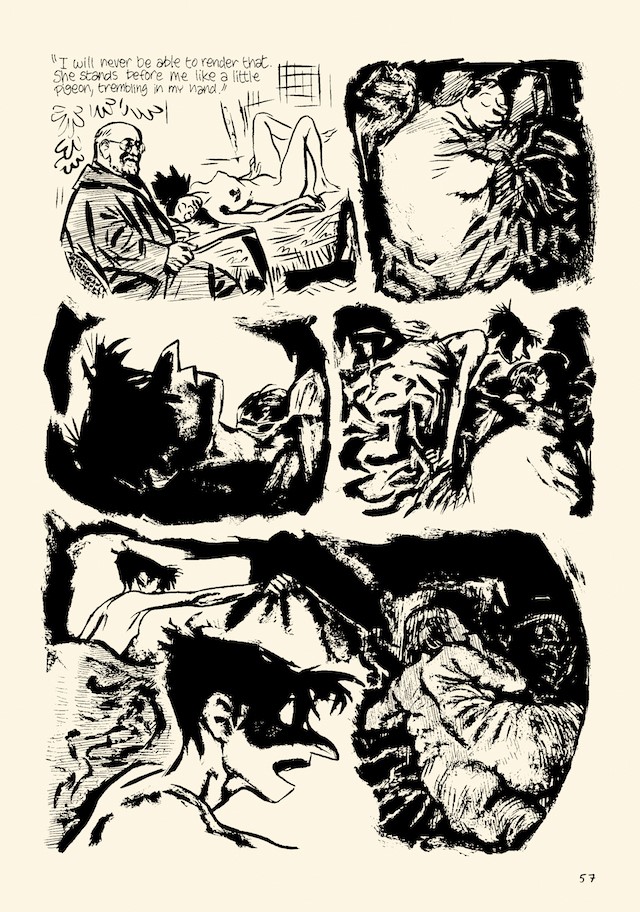

It’s not like this is an endless slog of man’s inhumanity to woman, though, although plenty of that is on offer and depicted in true and unflinching body-blow fashion. There is a softer side to Blutch, as evidenced most obviously by those aforementioned dance sequences, which underscore the artist’s intuitive understanding of each movement, as well as the absolute commitment of the dancer herself to seeing her performance through at any cost. That cost may sometimes be great, but the idea of who is in control is often a very open question — as one of Blutch’s female dances and is stripped naked by her partners in her routine, for instance, a painter appears to record his impressions of it all, only to transform into a vaguely Lovecraftian grotesquerie, while those doing the disrobing break apart into less-than-precise geometric shapes, leaving us to wonder who is an abstraction, who is real, and who really holds the power here, even as a frisson of sexual tension and terror increasingly fills the air and the page.

Another constant in Mitchum is overt cinematic references and even, for lack of a better term, “guest stars.“ The titular Mr. Mitchum is visually explored at every phase of his career, from young tough guy to — well, old tough guy, and we’ve got Pam Grier at her absolute action-queen peak as mentioned, but Jimmy Stewart’s on hand for some grim “festivities,” as well, and in one the most mysterious offerings in the entire book, the “extras” section contains a fairly fleshed-out Sergio Leone-style Old West tale of kidnapping and revenge that Blutch ended up layering underneath one of his dancing vignettes, thereby drawing some interesting parallels worthy of consideration, but, perhaps, undercutting some of the raw impact that the uniquely feminist take on western tropes would have had on its own. Oh, and if painting is more your bag than films, fear not — Henri Matisse is on hand for a cameo as well in a story that outright begs for direct comparison to one of his most famous works, The Dance. Do try to contain your surprise.

That being said, please don’t make the mistake of thinking that you know what to expect on any given page of Mitchum. Unrestrained imagination married with impeccable aesthetic sensibility and absolutely masterful execution is the only “rule” here, and, beyond that, Blutch simply goes where his muse takes him. That means we return to certain central obsessions and concerns time and again, sure, but they’re never presented the same way twice, nor are we as readers and observers — hell, I almost feel like saying voyeurs, so intimate and unguarded are the scenes we’re privileged to bear witness to — spoon-fed anything so clumsy or dull as absolute, hard-and-fast meaning. And that may be the most exciting thing about this book — Blutch’s intentions are never concealed, very often they’re in no way even subtle, but he has enough faith in his vision and his skill to leave the final act of piecing it together up to you. If you feel up to the task — and can handle some beautifully-illustrated instances of extreme ugliness along the way — what you’ll find here is one of the most complex, challenging, and rewarding comics you’ve likely read in quite some time.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply