In 1967, French philosopher and critic Guy Debord published The Society of the Spectacle, in which he analyzed the phenomenon he named the Spectacle—the increasing and many-faceted hegemony of the hyper-commodified market economy over all aspects of life and society, from the way we consume to the very way we perceive and engage with the world around us. Life, Debord claims, has ceased to be experienced and has become, instead, represented, as the Spectacle has turned us into label-obsessed (and, consequently, brand-obsessed) creatures whose hollow external has, in fact, become the internal. Under communist thought the workers are supposed to rule over the product, but the function of the Spectacle insinuates the capital-P Product into every aspect of life and thought, inverting the power dynamic so the product rules over the docile, passive, alienated workers, making them only capable of experiencing the world through the prism of Product, a hyper-relativistic nightmare.

Almost fifty years later, 2016 saw the release of two texts seeking, perhaps unconsciously, to exemplify Debord’s points before an English-language audience: Fantagraphics published Lucas Varela’s The Longest Day of the Future, while the comics division of the New York Review of Books published their edition of Hariton Pushwagner’s Soft City (actually completed, but unpublished, 41 years prior). What impressed me about the two books is the way that, even though each set out to do entirely different things, they seem to represent two complementary facets of pretty much the same phenomena in a life, and a world, that can only be experienced and engaged with through a brand logo.

Soft City and The Longest Day of the Future both start with a fairly similar premise: a day in the life of a company drone in a mega-city fully run by a massive omnipresent corporation in the former’s case, and divided between two such corporations in the latter’s case. Where they diverge is in creative approach: I think it’s fair to say that Varela’s book is geared more toward a traditional audience-oriented entertainment, whereas Pushwagner operates in a mode of experimental meditative desolation, taking an approach that lies somewhere between documentarian and almost propagandist (which is not to say Pushwagner believes in the righteousness of his book’s visions, but rather the opposite—he uses the visual and narrative languages of totalitarian propaganda with a great deal of cynicism, the façade of conviction on the page hiding sheer terror just beneath the surface).

One of the greatest dangers of the Spectacle, as Debord breaks it down in his book, is the way its omnipresence allows it to turn detriment into benefit, taking away most any weapon from its resistance by internalizing its contradictory states and turning them into weapons not in the service of the resistance—but of the Spectacle itself. This manifests very clearly, for example, in the concept of the vacation, a motif that both Soft City and The Longest Day of the Future choose to feature: the modern purpose of the vacation, among those for whom it is a genuine disruption of schedule and routine, is for one to “recharge” in order… to get back to work. That is, one does not vacate for vacation’s sake but, paradoxically, in order to prepare for more work, turning the lack of work into its own form of work.

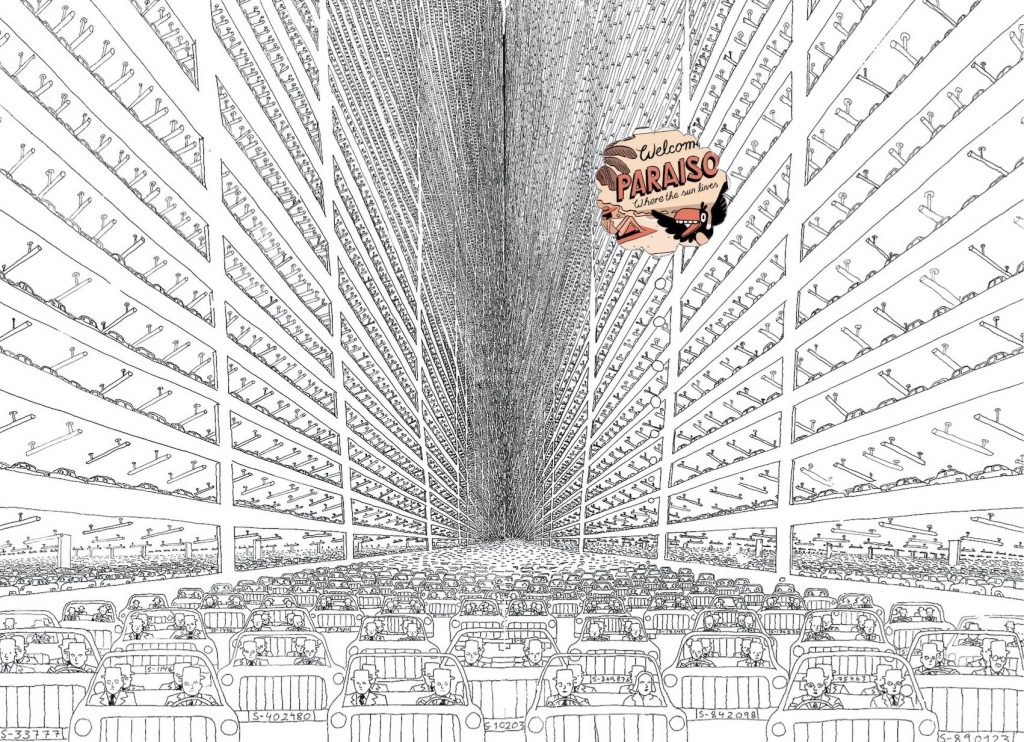

Soft City displays the many factory workers in their cars on their way to work, and one of them appears to daydream about a nice tropical beach, in a similar way to how the first page of The Longest Day of the Future features one of the untold millions of corporate employees pressing a gun to his head in the office restroom while looking at the one vestige of hope he still has left: a postcard for a beach resort named Paraiso. When a different employee—our supposed protagonist, who is as unremarkable in the eyes of the corporate state as the rest of his drone-kind—finds the postcard and keeps it for himself, he finds himself daydreaming about this tropical Arcadia; et in Arcadia ego, says the state, as the dreamer approaches a figure who, from a distance, appears to be a beautiful woman in a sun hat, but upon closer inspection reveals themself to have the animal-like head of the corporation’s mascot with its haunting stiff smile. As the mascot-seductress pins the employee to the floor, thousands of tendrils launch from its mouth at him, waking him up. Back to work! By the end of the book the employee will find himself in possession of an alien portal and attempt to go back, one last time, to this Paraiso, but the specter of work will still haunt the beaches of imagination, and the employee will destroy this portal. He’s resigned himself to his fate, to the corrosive embrace of the Spectacle.

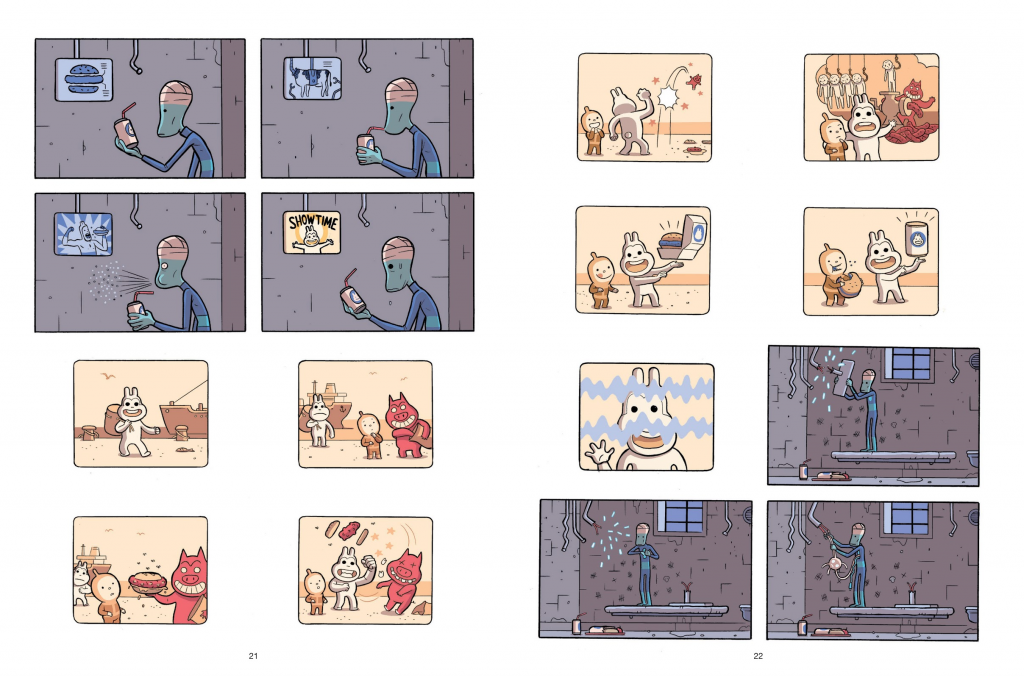

This extends beyond vacations and into everything one might define as recreation (or as “non-work”). Entertainment, too, has to comply with the Spectacle, reinforcing it at every choice, either actively by way of congratulation or passively through simply staying out of its way. One can’t help but notice, for example, that the only real mention of “art” or entertainment in The Longest Day of the Future is in sequences displaying animated cartoons in support of and presumably produced by the two warring corporations; each sequence displays its preferred brand as the heroic (or at least much-cleverer) winner and the enemy as the pathetic villain, and ends with the triumphant party offering the innocent bystander a reward in the form of branded food and drink. In a world torn between two monolithic hyper-corporations that seem to have successfully conquered every field of commerce and thought, it should come as no surprise that the brand becomes sustenance on both the physical-literal level and the metaphorical level, and, ipso facto, that any distinction between art (that which is often bestowed with the clichéd title of “food for the soul”) and advertisement should be rendered irrelevant.

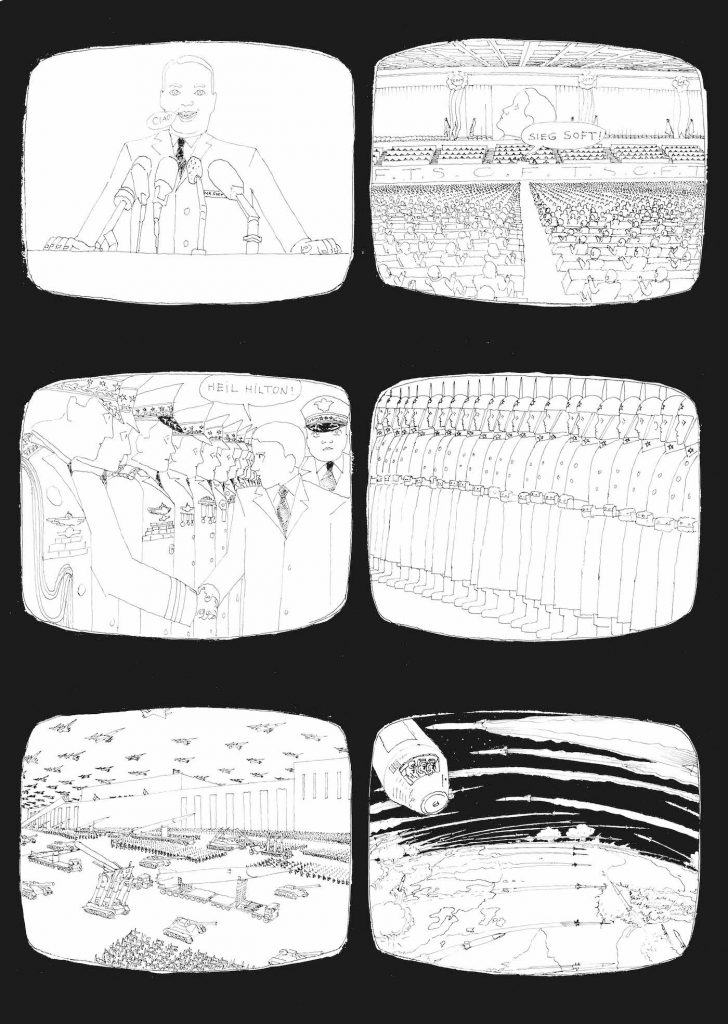

Soft City, for its part, features Soft T.V., divided by Pushwagner into three parts: fiction, represented here by a western film which, in a break-neck speed, goes from violent (but surely righteous in the moral realm of the film) to romantic as the Heroic Cowboy gets the Beautiful Woman; news/propaganda (if there is even a difference in this corporate-ruled world) featuring a montage of weapons and war as well as a political leader calling out “Sieg Soft! Heil Hilton!”; and, finally, sports, here represented by a soccer game. The messaging and underlying ties are clear: the western genre’s glorification and auto-mythologization of white America, the fascist tendencies of brand capitalism, and, finally, competitive sports as their own form of proxy-war politics. The final choice is perhaps the most subtle (in that it’s easy and tempting to take sports and ball games at face value), but, personally, even though both works were released decades after Soft City was completed, it put me in mind of Ben Passmore’s Sports is Hell and J.G. Ballard’s final novel Kingdom Come, both setting out to investigate the underlying racial and social politics of sports and their fandoms, with the latter drawing lines into larger patterns of the same fascist capitalism as Pushwagner’s vision.

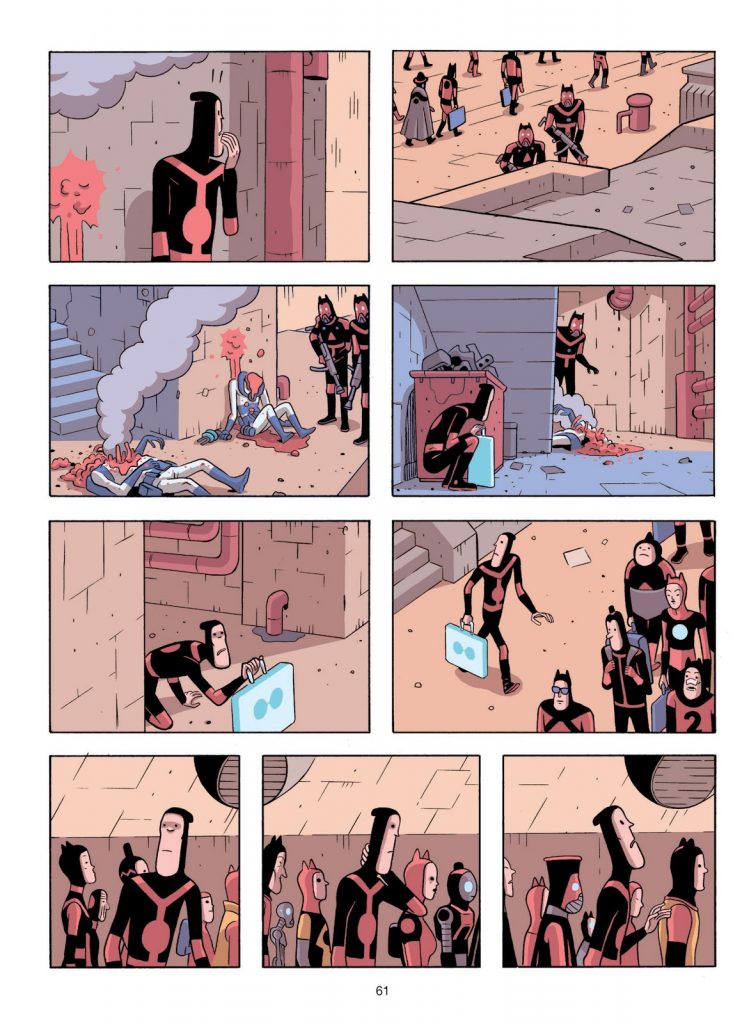

Both Pushwagner and Varela’s worlds, then, are built on infrastructures of violence, simply because violent zeal is the only glue that is passionate enough in its lack of rationale to protect the system; it serves as a form of perpetuum mobile that seeks to rewire the minds of its occupants and render the concept of pain (both the sensing and inflicting thereof) so entirely foreign, so far beyond any moral or ideological event horizon, that it becomes the perfect weapon, simply because the person wielding it doesn’t even realize it; just as one scene in Soft City showed an employee on his way to work dream about a beach vacation, the mirroring scene, showing the men as they drive back home, sees several of the men dream about piloting a plane at wartime, while just outside one dreamer’s car a man is beaten by another, and cries out for help. No one, we can pretty safely assume, will heed his call. The difference between the two worlds, of course, is in the way each is ruled: while the world in The Longest Day of the Future is, as described, torn between two corporate empires in a constant state of only-barely-cold war, Soft City only has one ruler, the Soft Corporation for which the city is named, and it is at supposed “peace,” as much as such a state of docility in the panopticon of the corporate state can be described as peace.

When one asks oneself why, then, there is such an emphasis on imagery of war and weaponry, the answer becomes rather clear: the two stories could well be framed as the two main phases of the formation of fascism, with Soft City serving as the first stage as the nation only builds itself around its own romanticized and valorized identity and mythology, and The Longest Day of the Future being the more advanced stage, as the nation finds itself an enemy to build itself around or against. The concept of “Nation”, after all, is a brand taken from the corporate plane to the political, engaging in similar tactics on slightly different terrain; it asks for your fidelity, for your business, and, in exchange, it supplies you with a (false, fleeting) sense of security, projecting all of your positive feelings onto itself (subsequently reflecting them onto you, the customer) and casting all of your fears and anxieties out onto whatever lies outside the territory of the brand. One still wonders, though, where the enemy of the Soft City will come from, given that any references to the outside world are anecdotal, insignificant; who, in such a case, could be a threat, other than the inhabitants themselves?

But, if the inhabitants are threats, they surely don’t know it themselves; they are far too weak in the eyes of the Spectacle to peacefully change their own lives, let alone deliver any meaningful shock to the system. Even the landing of an alien spaceship that presumes to be the inciting incident in The Longest Day of the Future doesn’t amount to much in the way of “making a narrative difference,” as, even though the tools of the aliens are used as weapons in the battle between the two corporations, it’s hard to imagine that this battle would not have happened otherwise. This external disruption hardly even registers on any grander scale because the characters care about the external as much as they care about the internal, which means “hardly at all.” This sort of desensitized resignation is embodied by the evidently corporate-sanctioned pills that characters in both books take at the start of every day, comparable to Brave New World’s Soma, but I can’t help but wonder if those pills even change anything, if they add anything beyond a clear visual signifier; if anything, the Spectacle appears to run so deeply in their systems that no pill could change their condition in either direction.

The people in both Varela and Pushwagner’s works are, rather explicitly, miserable, to varying degrees of self-expression; even though his book is a non-verbal story, Varela’s characters seem more capable of emotion, of slightly deeper thought, whereas Pushwagner’s style of misery, expressed in shallow thought balloons with hardly-meaningful id-driven thoughts, a wife thinking her husband is a “crazy idiot” in the morning and thinking “I’m tired” in the evening, even though we know, under the pre-established rhythms of the Soft City, that nothing will be done to change this situation. In their conversations, too, they only barely communicate; this same wife asks her husband if he had a nice day at the office, and he replies with the oppressively-unremarkable “As usual, dear,” and that’s the depth of conversation, the depth of reality, under the Soft regime. This is, of course, the source of the horror at the core of these worlds; the things that are said but not truly remarked on, having been fully obviated. The narration in the Soft City office sequence declares: “If you don’t make it, you’re fired. If you’re fired, you are finished.”—this is no understatement; of what worth is a dehumanized worker, once their work has been taken away from them? Off to the glue factory of the Spectacle they go. The Paraiso postcard in The Longest Day of the Future also has that form of harrowing undercurrent, as it proclaims the tropical resort to be “Where the sun lives!”—a pseudo-utopian statement until one stops to ask what happens to the sun outside of Paraiso, and why it’s come to be rejected, to be dead (presumably because it is a major force that the corporation, for once, cannot control).

It’s interesting to examine the convergences of Soft City and The Longest Day of the Future, partially because of how different they are as works. As mentioned earlier, I don’t think it would be wrong to call Varela a more entertainment-minded creator than Pushwagner’s pop-art auteurism. As such, there is much more of an emphasis on plot and on overt humor to Varela’s cyberpunk slapstick. I am (somewhat begrudgingly) reminded of a stand-up bit from Seinfeld, wherein Jerry Seinfeld discusses the two “kinds” of Nazi salute: the dramatic full-body salutation gesture and the casual, floppy-handed salute one would use around the “office,” amidst the banalest of office patter. Somehow this strikes me as a distillation of the variations in sensibility between the two books: The Longest Day of the Future is much less “about” the capitalist dystopia it occupies, as it serves for the backdrop, but this only underscores the sinister element of it through sarcastic resignation to the absurd. What Varela treats as backdrop, though, Soft City and Pushwagner will take to the forefront, as the infrastructure becomes the message itself.

This, of course, extends to the cartooning work on display; Varela’s art is confident, smooth, even-handed, and generally much more “pleasing” on a purely aesthetic level, while Pushwagner’s art sports a shaky, primal sensibility that could have been described as “primitivistic” if not for the density of vision and detail. Pushwagner’s art also leans heavily on a Kubrickesque symmetry and mirroring effect, which operates as an interesting contrast to the inherent id-driven lack of symmetry of his style, elevating the smothering effect of the work. It’s interesting to note, too, that, while The Longest Day of the Future opts for a much more “familiar” colorful far-future aesthetic, Soft City is almost entirely uncolored and even unshaded, the only use of color being in the traffic lights in the driving sequences. But the differences in tone and aesthetic, if anything, just emphasize the similarities in viewpoint.

It’s been 171 years since the release of The Communist Manifesto and 52 years since that of The Society of the Spectacle. If anything, as brands lay and reinforce their claim over our every waking thought, the messaging of the latter has only grown more pertinent, and the major rallying cry of the former more utopian, more unattainable. While I’m wary of the idea that any work (or even collection of works) of fiction can serve as “the blueprint for where we are headed,” Soft City and The Longest Day of the Future seem despairingly pertinent, as they try to grab the reader by the shoulders and jostle them awake only to come to the conclusion that it is not entirely possible. “Workers of the Spectacle, unite,” they call out—“even though you have everything to lose, including, but not limited to, whatever still chains you to reality.”

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply