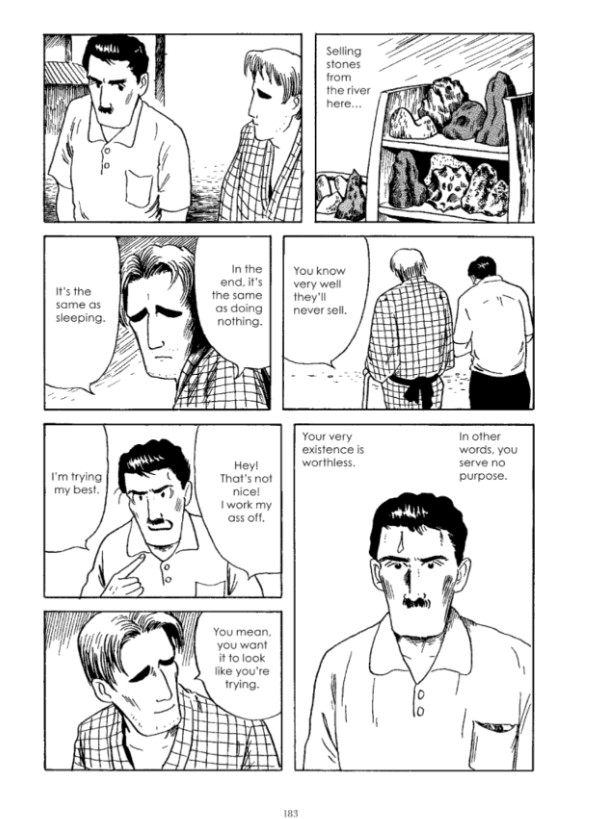

In Yoshiharu Tsuge’s The Man Without Talent, we first meet the protagonist, Sukezō Sukegawa, “reduced to selling stones” along the bank of the Tama River. His ramshackle kiosk sits in the shadow of a dam and a railroad. A peer tells him “ain’t no one gonna pay money for something they can get for free”, but Sukezō has already failed at dealing in antiques, cameras, and drawing comics, and selling stones is the last idea he’s got. The narrative sticks with Sukezō’s point of view as he attempts to make it in the stone selling industry, or what’s left of it. Along the way, we get monologues from bird sellers, bathhouse managers, and trash collectors. These dialogues critique the import of American culture, of the young allowing habits of the old to die, and of the futility of attempting to succeed, whatever that vague and ambiguous word means.

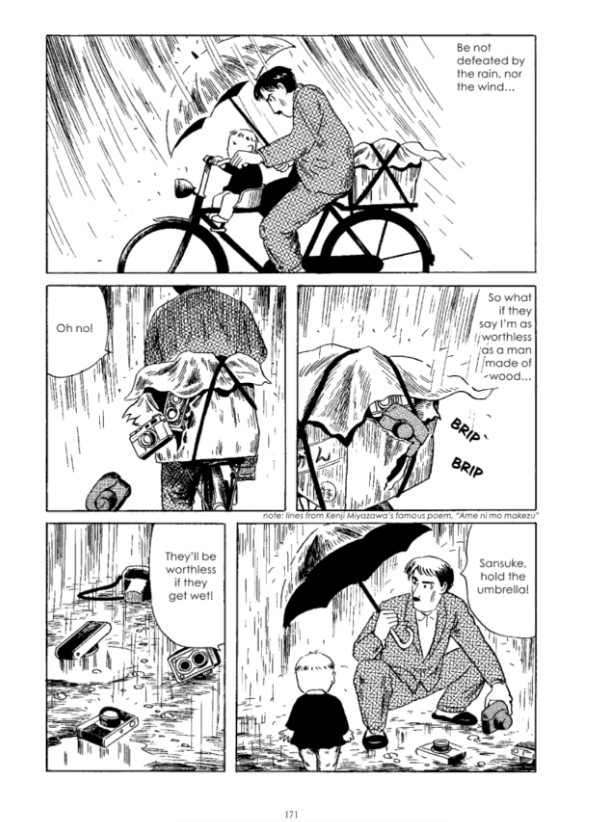

The Man Without Talent produces a feeling of life on pause. Sukezō is often with his family, a wife and son, although, thanks in part to their poverty, home life is fraught. Unfortunately, Tsuge excludes Sukezō’s wife from the narrative by obscuring her face throughout the first three chapters. The son gets a better deal, and he works as the living heart of the book. More than once in this story, he arrives, looking as if he’s about to cry, to tell his dad it’s time to come home. These moments – often at the end of a chapter, interrupting the father’s frustrations – when the kid stands there, a patch on the shoulder of his jumper and looking forlorn, are heartbreaking.

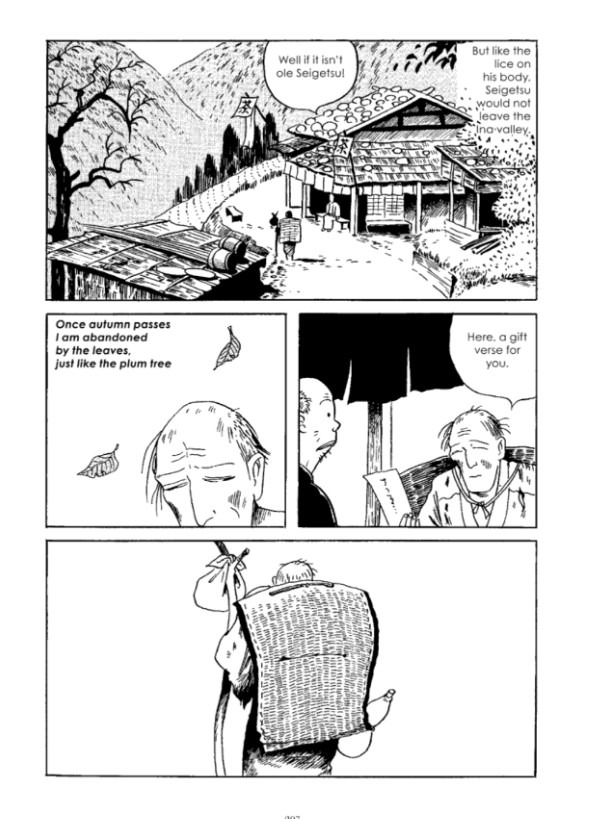

There is much blank space in Tsuge’s panels, as if the characters are lost in some vague mist, unable to see a horizon. Tsuge’s people are expressive, and each of the characters seems to fulfill an unrevealed quota of stereotypes. The page layouts are rational, there’s only a handful of splash pages and half page panels, and they’re used to great effect. The pacing is sublime; The Man Without Talent has a meditative rhythm. There are panels where we’re asked to witness Sukezō killing time, or pay attention to nothing more than a gust of wind or the detritus of a collector’s store. Tsuge‘s environments are rendered with a little more realism than the people. He uses halftone to shade and crosshatching very irregularly. The parallel lines that he employs, at various degrees of separation, to add weight to the diegesis, produces an organic and dusty look, reinforcing the sense that this is a story about people close to the earth. It’s worth adding here that it’s regularly, if very darkly, funny.

Tsuge started producing work for the alternative manga magazine Garo in the late 1960s. These stories, according to the introduction of this book (by its translator, Ryan Holmberg) became some of his most popular work among his fans in Japan. The Man Without Talent, already available in French, is another favourite. This English language version, published by New York Review Comics earlier this year, has started what looks to be an exponential growth of Tsuge’s popularity among English language readers in upcoming years. It’s a one-shot that works as a primer to Drawn & Quarterly’s ongoing seven-volume reprinting of Tsuge’s mature work, a series which starts with his Garo stories.

Around the same time Tsuge started his Garo work, the Japanese student organization Zenkyoto had numerous skirmishes with police on Tokyo university campuses. These uprisings were as fuelled by an interest in the philosophies of nihilism and existentialism as they were a reaction to that moment in the country’s Shōwa period (1926–1989). This moment was characterized by a boom of heavy industries in Japan and the country’s political class allying with American economic interests. From this milieu, an artistic movement called Mono-ha appeared. Meaning “School of Things”, Mono-ha art focused on emptiness and organic materials. Sloganeering and definitive statements were sidelined for a meditative production of space.

In an interview with French journalist Henri-François Debailleux, Lee Ufan, one of Mono-ha’s cofounders, says: “Modern man is afraid of emptiness and refuses to acknowledge it. This is because emptiness, the void, corresponds to what man has not filled, to what he has not done. I myself am very skeptical about the fact that we attribute value only to what man has done.” Later in the same conversation, Debailleux asks Ufan about his use of untreated materials, and why a lot of his work involves taking stones from the wild and giving them a new context. Ufan says: “With the introduction of the object produced automatically by a machine, the myth of personal expression took a real knock. What can you do after the advent of an artwork that is only partly the expression of the artist? What can you do after the work that criticizes industrial society? My response to this is to introduce what is not manufactured”.

While The Man Without Talent was both produced and set in the 1970s-80s, some time after Japan’s moment of social upheaval and the rise of Mono-ha, it is not difficult to see its protagonist (often referred to as an avatar of Tsuge himself) as a somewhat accidental and desperate practitioner of such an art. This is a book about the margins: about the margins of economic development, about the margins of culture, about the margins of history, about the margins of Capitalism itself. These margins are spaces in which people and things become lost, as Sukezō and his family, struggling with poverty, are in this book. The Man Without Talent works as a critique of, to borrow and update Ufan’s phraseology, the attributing of value to things that people have done, and also interrogates the notion that people must do things (especially work) in order to be valuable.

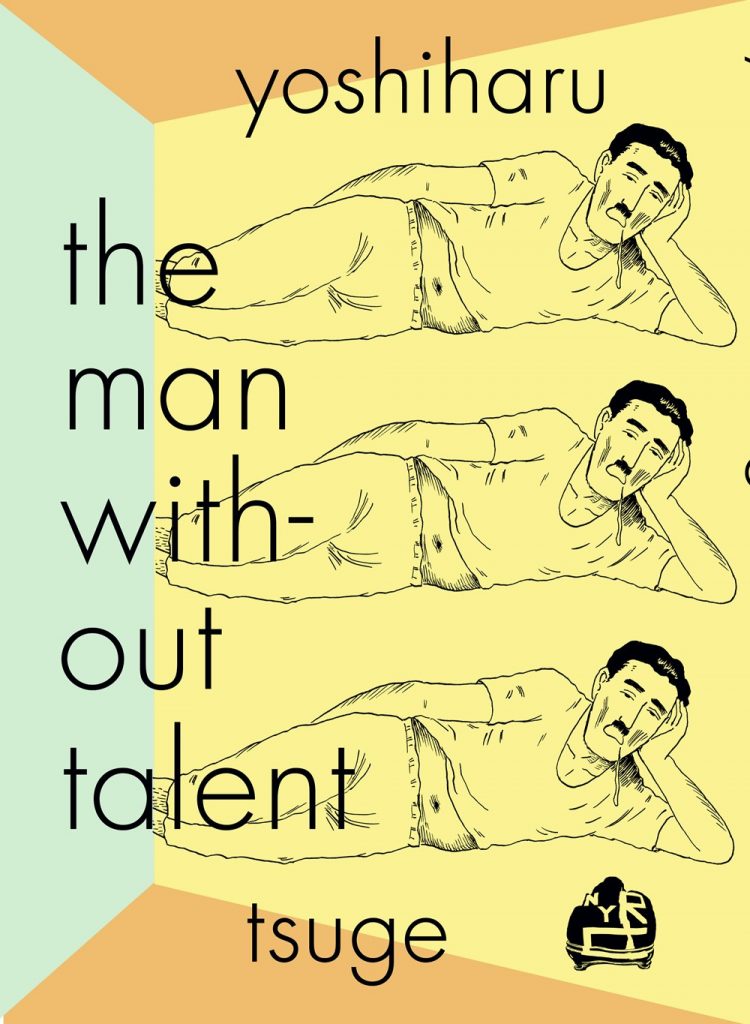

In this instance, the man without talent is a man defined by his economic unviability. Early on, Sukezō is asked what is different about two stones that closely resemble each other. He replies: “The spirit. The shape.” He could equally be talking about himself, and all the other people who find themselves washed up, metaphorically speaking, along the bank of the river, scratching a living while dissolving into the great mass of the impoverished, the sound of the train rumbling overhead, the vibrations of modernity rattling the cage of tradition. Sukezō’s response to all this disruption? More than once he reclines on his side, head held in the palm of his right hand, propped up by his elbow, as if letting the world wash over him.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply