If one accepts — and I frankly don’t see why you wouldn’t — that the Fort Thunder crowd were the pre-eminent influences on both their contemporaries as well as the generation of independent/”alternative” cartoonists that have followed in their wake, then it makes perfect sense to be of a mind that whoever it was who, in turn, influenced them the most would likely be, sheerly by default if nothing else, the most influential cartoonist of the modern era. And while that’s a borderline-brazen label to be attaching to anyone, when the person on the receiving end of the title they never asked for is Gary Panter, the most natural and obvious reaction is probably something along the lines of “oh, well — yeah. I mean, who else could it be?”

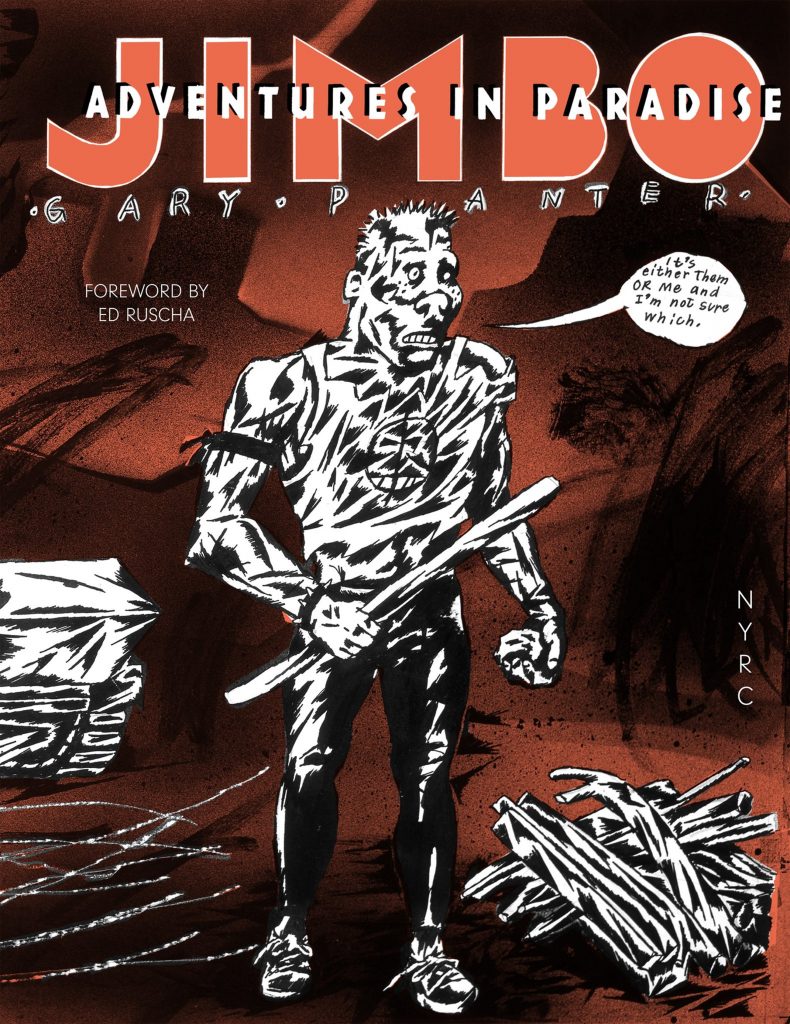

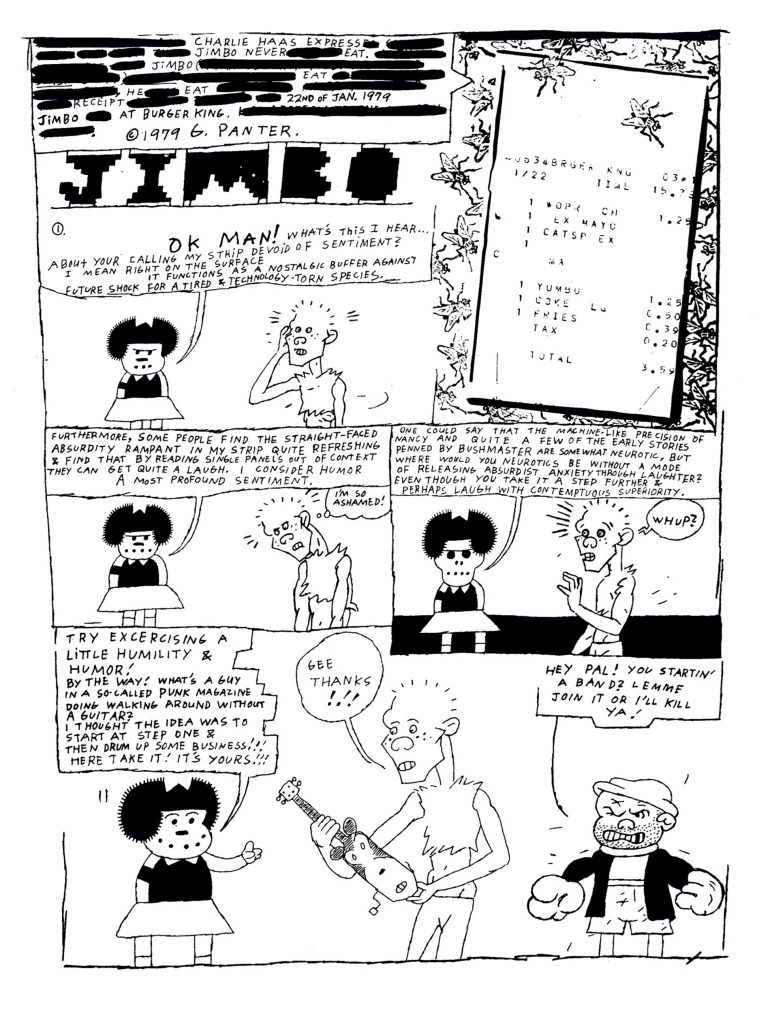

And so it has come to pass that the medium’s onetime most-radical talent is now an institution unto himself, which means that, as readers, we’re in a hell of a lot more exciting and interesting place than we were back when Panter began the work that would eventually be collected as his first long-form graphic novel, Jimbo: Adventures In Paradise. Nicole Rudick does a far better job of positioning Panter within various cultural and artistic milieus that came to a head during the period of 1978-88, when the story was created and serialized, in the afterword she provides for the book’s new edition from New York Review Comics than I have the time or patience to, but I draw attention to her superb essay because it does, in fact, go some way toward bearing out the admittedly grandiose statement I kicked things off with here a moment ago. Said new edition, then, is no mere “deluxe format reprint” of an important book — it’s a welcome return to the fold, after a long absence, of a seminal work in the history of non-corporate cartooning.

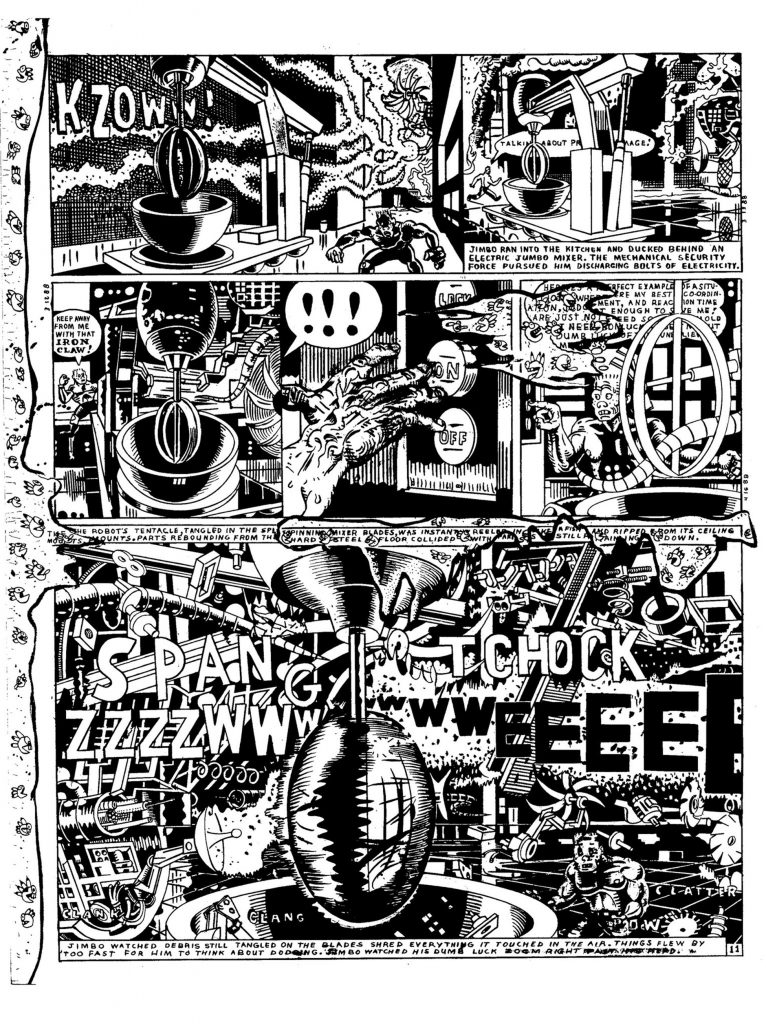

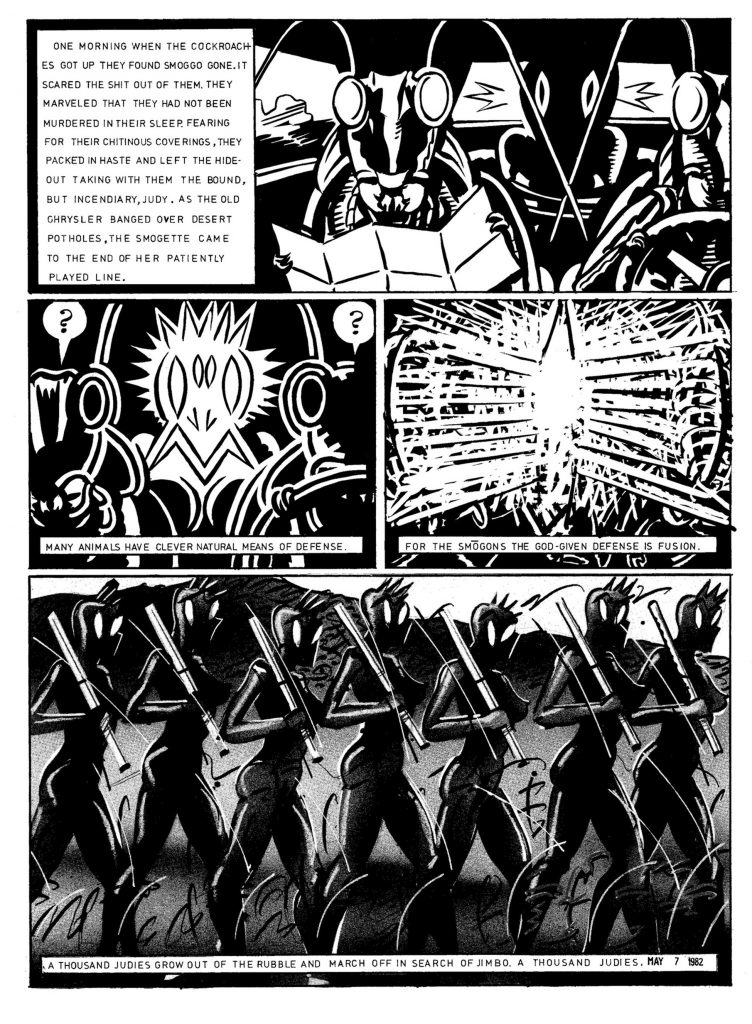

In an act of unforced irony worthy of Panter’s own finer moments, it also turns out that this release couldn’t be more timely, in that it appears increasingly as if the real world is finally catching up with the cartoonist’s visionary absurdism. The streets of your city may not resemble the hallucinatory industrialism of the fictitious Dal Tokyo physically, but in terms of character and temperament, who can argue that we haven’t arrived, culturally speaking, at something very much like it? I mean, the notion of having a firm grip on consensus reality is pretty well out the window because there no longer is such a thing as “consensus reality,” thus Panter’s ever-shifting environments — to say nothing of his ever-shifting art styles — stand some 40 years after their id-transmitted creation as something the artist himself never likely intended them to be: visual representations of society’s collective mental zeitgeist. Funny how things turn out, isn’t it?

For that matter, who hasn’t felt a bit like protagonist Jimbo in recent years? We may not be called upon to prevent the detonation of a nuclear warhead as he ultimately is here (at least let’s hope we never are), but his trademark attributes of being forever and always out of his depth, of being anxious to the point of neurosis, of finding himself continuously conscripted from the role of passive observer into that of active (if accidental) participant? These are things many of us know all too well, as is also the case with his “fallback position” of only finding something akin to bliss in the haze of unawareness. When the going gets tough, the smart money isn’t on pretending you don’t know what’s happening to maintain your sanity, it’s on legitimately not knowing what’s happening in the first place.

Still, while others have opined that Jimbo is some sort of idiot savant, I don’t think that characterization holds any more water than earlier critiques of Panter’s deliberately amorphous cartooning as being naive for its own sake — in fact, in re-reading this material for the first time in a good couple of decades myself, my earlier belief that he’s the closest thing to an actual “everyman” figure one can get without being too painfully obvious about it was only reinforced. By turns a cipher, a hopeless romantic, a bumbling clown, and even a hero when he needs to be (rather than when he wants to be), he’s an effective distillation of much of the human experience in microcosm — something that even applies to his varied visual presentation. I mean, have you looked at photos of yourself from ten years ago?

To return things to the subject of NYRC’s new printing specifically, in addition to generally (it must be pointed out there are some issues with cropped art on certain pages) boasting the kind of high production values we’ve quickly become accustomed to from them, and that work of this level of import both deserves and, frankly, demands, perhaps the greatest service it does is to demonstrate how so much of what we take for granted today in small press and self-published comics — from visual and narrative experimentation to subject matter that is as challenging and rewarding conceptually as it is aesthetically — only came to be the prevailing state of affairs because Panter did it first. That Jimbo: Adventures In Paradise has turned out to be a remarkably prescient work as well (even going so far as to help kick-start a resurgent wave of interest in Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy that shows no sign of cresting) is just icing on the cake. From Slash to the L.A. Reader to Raw to Pantheon to the New York Review of Books, the “prestige level” of the publishers attached to this comic has only gone up over the years, but remarkably enough, the work itself hasn’t stayed still, either — it was showing the way forward for comics way back when, and it still is now. Who knew that when we first visited Dal Tokyo that we’d end up staying — and that we’d still be trying to get the lay of the land? It’s a damn good thing, then, that exploring it never gets old.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply