Chloe and Phoebe are breaking up.

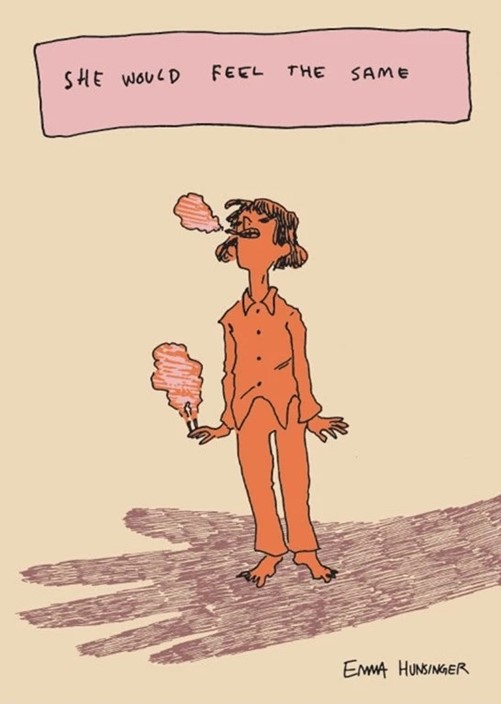

It is the end of a seven-year relationship between the two women, but they approach it with “stoicism”, closing the seven-year chapter of their lives with a civil handshake after “diplomatically” dividing their worldly possessions. They are, after all, adults, and, as Chloe tells it, “we woke up one morning and apropos of nothing we were no longer in love.” However, on the cover, Chloe smokes two cigarettes in the shadow of a hand reaching out to shake. Are seven years of love so easily set aside without a single tear? So begins Emma Hunsinger’s She Would Feel the Same, ostensibly a breakup comic that bucks the genre expectation of heartache and morose sentimentality. “It’s still a love story,” Chloe demurs, “just maybe not a ‘good’ love story.”

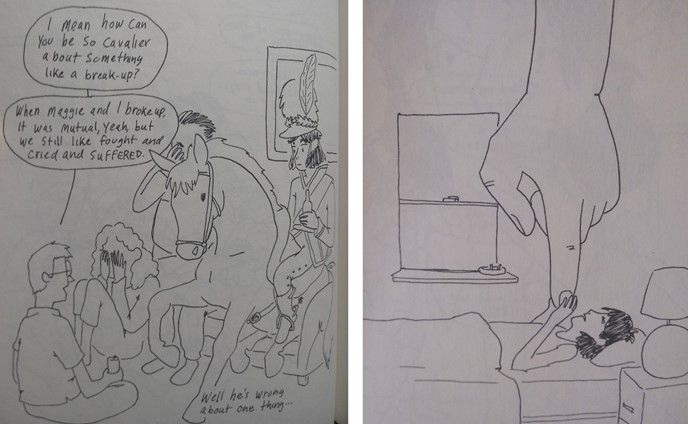

Expectation is core to the comic’s central inquiry. Preoccupied with how she is perceived, protagonist Chloe is more interested in subverting the expectations of others than living up to them. “Have you ever had the displeasure of listening to a story be told about you?” she asks the reader, as an acquaintance regales a gathering with the story of Chloe’s relationship’s bizarre demise, unaware that it is about the person sitting right across from him. Chloe’s indignation is situated in her desire to take ownership of her own story, but her discomfiture also stems from the way in which an outsider’s perspective on her breakup lays bare that it is maybe odd to end such a long-term relationship with a formal handshake. She can only fault the lousy raconteur on the details, correcting him to his embarrassment that “It was seven years. Not ten.”

So, too, is the comic concerned with the idea of what it means to be “good” in the context of a relationship. Chloe’s self-deprecation when she admits that her love story may not be “good” implies her beliefs both that love is something you can be proficient at, and that some love stories are objectively better than others. These ideas are somewhat at cross purposes. Chloe resists at every turn the suggestion that a breakup must be, by definition, dramatic, but it is precisely the lack of drama to which she feels she must respond when she tells us the story may not be “good”.

Chloe’s strictest expectations are self-imposed. She is seeking an elusive “perfection” that she believes is nonetheless, in some way, attainable, and she resists vulnerability even in a moment of potential heartbreak in this quest. She cannot understand the man at the party insinuating she is an emotionless robot or that she and Phoebe must be hiding a shattering infidelity. “It was perfect,” she tells her best friend Kira afterward. “No drama, nice and neat…It’s a great way for something to end…I thought people loved immaculateness!” When Kira responds that “They do! That’s what Christmas is all about.” I was reminded of last year’s American romantic comedy Happiest Season, a sweet if formulaic holiday film distinguished by its central focus on a lesbian couple. The prevailing sentiment online seemed to be that, yay, gay people continue to enter and claim their slice of mainstream pie, even if it is within a weirdly heteronormative framework of saccharine unsubstantiality.

What is “perfection” and in what ways have our notions of what constitutes an ideal been heavily shaped by external forces? There is a kind of idealism in Chloe’s certainty that even the worst or most difficult things in life can at least be moments of grace and maturity. It is frustrating for her to encounter from others the implication that her lack of messy emotion might represent a defect rather than an advantage. Hunsinger communicates this both through narrative and inventive artistry that both give dimension to Chloe’s internal tumult.

Hunsinger’s visual style is a delight. Her line, spare and deceptively simple, is cartooning at its most essential. No mark is wasted or unintentional. She frequently employs expressionistic details, sometimes in clever visual gags such as when a man calls Chloe cavalier at an apartment gathering and Hunsinger draws her suddenly atop a horse in full wartime regalia. But, just as often, these images express, far better than words, the overwhelming subjective totality of an emotion like crushing anxiety.

These images that play with fantasy and sense of scale are key in conveying Chloe’s emotional state. While some of her narration and dialogue may be more revealing than she intends, she’s a character that intentionally plays it close to the vest when it comes to how she’s feeling.

We gradually find that Chloe’s resistance to vulnerability, her emotional stoicism, extends beyond and precedes her relationship with Phoebe. Hunsinger beautifully encapsulates the way in which love requires opening yourself up to the possibility of pain as Chloe narrates the change that came over her after she fell in love with Phoebe. With a note of pride, she describes how, “Before I met Phoebe, I never cried at anything. Not when bad things happened, not in sad movies, not even when people died. But after I fell in love with her, anything could make me cry.”

If falling in love with Phoebe opens her to vulnerability, their breakup closes her back up. Chloe throws herself into her pursuit of perfection, defining perfection as the appearance of neither effort nor feeling. She peels oranges obsessively trying to achieve (unsuccessfully) an unbroken peel. She goes on dates, she chain-smokes with aggressive enthusiasm. Nothing can hurt her! The only odd thing is that she keeps waking up the wrong way in (or underneath) her bed…

She Would Feel the Same is not only about Chloe’s resistance to vulnerability, but also about whom we allow to be vulnerable. As a woman and a gay woman at that, Chloe struggles with the insidious weight of gendered expectations. The catch-22 is that you are damned to respond to prevailing stereotypes even if you choose to try and subvert them. Chloe’s attempts to embody an alternative femininity embrace aspects of toxic masculinity in the bargain, situating strength in the denial of emotions that are perceived as admissions of weakness. Chloe’s response to her breakup, the way she defiantly smokes two cigarettes simultaneously, and the moment when she soldiers through a cough at work until forced to go home because she is bringing up blood all emblematize how her subversion of traditional femininity has become as much of a prison as compulsory traditional femininity itself.

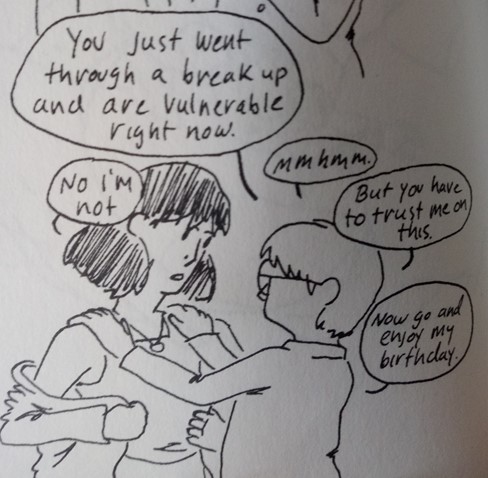

All of this comes to a head after she goes home with the brash, rude, notorious flirt Cecilia even after Kira warns her against it. Of course, for Chloe, being warned away from something is as good a reason as any to do it. However, Cecilia’s sense of perpetual humor, as much as her rodomontade, serves as a possibly painful reflection to Chloe of the potential extreme to which such a persona might be carried. As the thought occurs to her that Phoebe is no longer the last person she slept with, Chloe’s armor begins to crack.

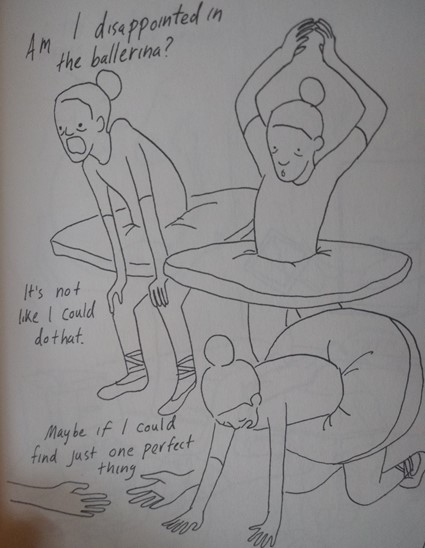

This armor is rooted in Chloe’s flawed understanding of genuine strength. Hunsinger employs the recurring motif and metaphor of the ballerina to enormous effect. On a date to the ballet, Chloe sits in the front row – the ostensibly perfect seat – which gives her a revealing and distracting view of the side of the stage where the dancers leave the spotlight. There, she witnesses their onstage composure dissolve as they take gasping breaths following their exertions. Chloe is astounded by the glimpse behind the curtain. “Do you know anything about ballerinas getting winded?” she asks her companion incredulously after the show. “I always thought ballerinas were perfect.” Chloe reflects on her reaction to this new perspective on ballerinas, asking herself if she is disappointed in the ballerina now that she has seen the illusion of effortlessness fall away.

The ballerina is a uniquely gendered symbol in the comic. We understand implicitly that ballerinas carry out feats of astounding athleticism while simultaneously maintaining a physique and routine requiring gritty asceticism. However, they do this to conversely perform the appearance of delicate and carefree femininity. They are associated with lightness, spareness, the color pink. The weightless, effortless fantasy of the ballet ironically requires dancers to shoulder an enormous weight of expectation to maintain. In the comic’s most striking image, Chloe wonders if she would feel differently if the ballerina had a gun. Suddenly, the sweating, winded ballerina assumes the posture of an action hero. The evidence of her effort becomes, instead of an admission of weakness, an emblem of her tenacity.

The comic’s title connotes the joy of requited love, but it also questions the supposed mutuality of the diplomatic breakup between Chloe and Phoebe. Does Phoebe feel the same? Kira questions whether the handshake is more about Chloe maintaining an illusion she has about her own identity and denying a confrontation with grief over what is being lost.

What Hunsinger subtly guides her reader towards is the realization that Chloe is having, too: that avoiding negative emotion and precluding even the appearance of hurt can never be anything more than a performance. No one escapes life unscathed, and if we succeed in concealing our pain, we will in consequence never connect with anyone and never process our wounds. That Hunsinger conveys this in a comic filled with visual inventiveness and sharp humor is a feat. She Would Feel the Same is an incredibly rewarding read, right down to its last page, upon which Chloe and Phoebe finally meet back up for the first time after the end of their relationship. Hunsinger leaves us with, at long last, an embrace between them and Phoebe’s tentative supposition that “it’s kinda funny that we shook hands that day…”

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply